The Case of Bucktown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Eye, Summer 2010

Right-Wing Co-Opts Civil Rights Movement History, p. 3 TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL R PublicEyeESEARCH ASSOCIATES Summer 2010 • Volume XXV, No.2 Basta Dobbs! Last year, a coalition of Latino/a groups suc - cessfully fought to remove anti-immigrant pundit Lou Dobbs from CNN. Political Research Associates Executive DirectorTarso Luís Ramos spoke to Presente.org co-founder Roberto Lovato to find out how they did it. Tarso Luís Ramos: Tell me about your organization, Presente.org. Roberto Lovato: Presente.org, founded in MaY 2009, is the preeminent online Latino adVocacY organiZation. It’s kind of like a MoVeOn.org for Latinos: its goal is to build Latino poWer through online and offline organiZing. Presente started With a campaign to persuade GoVernor EdWard Rendell of PennsYlVania to take a stand against the Verdict in the case of Luis RamíreZ, an undocumented immigrant t t e Who Was killed in Shenandoah, PennsYl - k n u l Vania, and Whose assailants Were acquitted P k c a J bY an all-White jurY. We also ran a campaign / o t o to support the nomination of Sonia h P P SotomaYor to the Supreme Court—We A Students rally at a State Board of Education meeting, Austin, Texas, March 10, 2010 produced an “I Stand With SotomaYor” logo and poster that people could displaY at Work or in their neighborhoods and post on their Facebook pages—and a feW addi - From Schoolhouse to Statehouse tional, smaller campaigns, but reallY the Curriculum from a Christian Nationalist Worldview Basta Dobbs! continues on page 12 By Rachel Tabachnick TheTexas Curriculum IN THIS ISSUE Controversy objectiVe is present—a Christian land goV - 1 Editorial . -

Louisiana Sheriffs Partner with State Leaders During Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike

HURRICANES GUSTAV AND IKE Partnerships Through the Storms THE ISIA OU NA L EMBERSH M IP Y P R R A O R G O R N A M O H E ST 94 AB 19 S LISHED ’ HERIFFS The Official Publication of Louisiana's Chief Law Enforcement Officers MARCH 2009 20 th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE SPECIAL EDITION Louisiana Sheriffs Partner with state leaders during Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike Members of the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness (GOHSEP) Unified Command Group performing statewide recovery efforts after Hurricanes Gustav and Ike. Pictured from left to right are Superintendent of Louisiana State Police, Colo- nel Mike Edmonson; Chief of Staff Timmy Teepell; State Commander Sergeant Major Tommy Caillier; Adjutant General, MG Bennett C. Landreneau; Governor Bobby Jindal; Major Ken Bailie; LSA Executive Director, Hal Turner; Director of GOHSEP, Mark Cooper. Photograph by Danny Jackson, Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association by Lauren Labbé Meher, Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association n August 29, 2008, exactly three years after Hurricane and the length of time it took to travel across the state. Every Katrina, Louisiana residents were facing an all-too-famil- parish in the state was impacted by either tidal surges, flooding, iar situation. Hurricane Gustav was nearing Cuba and, wind damage or power outages. With 74 mph hurricane strength Oaccording to most predictions, heading on a path that led straight wind gusts lingering over the capital city for at least two hours, into the Gulf of Mexico, putting Louisiana in eminent danger. meteorologists claim it was the worst storm to hit the area. -

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well LLC BOBBY JINDAL CAMPAIGN Report Number: 14629 Governor PO Box 82860 State of Louisiana Date Filed: 2/15/2008 Baton Rouge, LA 70884 Statewide Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule A-3 Schedule E-1 3. Date of Primary 10/22/2011 This report covers from 10/29/2007 through 12/31/2007 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general X 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more banks, savings and loan associations, or money market mutual fund as the depository of all 9. Name of Person Preparing Report Daytime Telephone 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 145 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 1999 No. 28 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was fied America. It is now time to set other citizens are guaranteed? Are called to order by the Speaker pro tem- aside the differences that have divided there two different kinds of citizenship pore (Mr. STEARNS). us along party lines and work together in our Nation, the example of democ- f for the good of the country. racy? Yesterday we commemorated George What is even more discouraging is DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Washington's birthday, an everlasting that not only the great expectations PRO TEMPORE model of leadership and achievement, for future success and equal participa- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- 200 years ago, as our first President tion do not apply to Puerto Ricans in fore the House the following commu- ably led the United States from revolu- the islands but that residents in the is- nication from the Speaker: tion into democracy. land will continue to lag further and WASHINGTON, DC, Today, there are many issues that further behind as they are fenced out February 23, 1999. claim congressional attention for im- from the rest of the Nation. I hereby appoint the Honorable CLIFF mediate action, including specific im- Throughout my political life, I have STEARNS to act as Speaker pro tempore on provements for Social Security, edu- fought to provide equality for the this day. -

Order and Reasons

Case 2:06-cv-09243-MVL-ALC Document 30 Filed 11/30/07 Page 1 of 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA CYNTHIA CANTWELL ET AL. CIVIL ACTION VERSUS NO: 06-9243 THE CITY OF GRETNA ET AL. SECTION: "S" (5) ORDER AND REASONS The court has considered the motions to dismiss, pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), filed by The City of Gretna; Arthur Lawson, the Chief of Police of the City of Gretna, in his official capacity (document #19) ; Harry Lee, the Sheriff of Jefferson Parish, in his official capacity (document #23) ;1 and the State of Louisiana through the Department of Transportation and Development, Crescent City Connection Division (document #22). The defendants move to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claims of 1) constitutional violation of their right to interstate travel, 2) violation of Eighth Amendment guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment, and 3) violation of their Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure. 1 Sheriff Lee died on October 1, 2007. Case 2:06-cv-09243-MVL-ALC Document 30 Filed 11/30/07 Page 2 of 9 IT IS HEREBY ORDERED: The defendants’ motion to dismiss the claim that the defendants violated their constitutional right to interstate travel is DENIED; The defendants’ motion to dismiss the claim that the defendants violated their constitutional right to intrastate travel is GRANTED; The defendants’ motion to dismiss the Eighth Amendment claim of cruel and unusual punishment is GRANTED; The defendants’ motion to dismiss the claim of unreasonable search and seizure under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments is GRANTED; The defendants’ motion to dismiss the claim of unreasonable search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment is DENIED. -

Fertile Ground: Women Organizing at the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Reproductive Justice

FFeerrttiillee GGrroouunndd:: WOMEN ORGANIZING AT THE INTERSECTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE AND REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE By Kristen Zimmerman and Vera Miao Fertile Ground: Women Organizing at the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Reproductive Justice By Kristen Zimmerman and Vera Miao ©2009 by Movement Strategy Center Commissioned by the Ford Foundation Printed in the U.S.A., November 2009 ! is report was commissioned by the Ford Foundation through a grant to the Movement Strategy Center (MSC). It was researched and prepared by Kristen Zimmerman and Vera Miao with support from MSC. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and MSC and may not necessarily refl ect the views of the Ford Foundation. ! e Ford Foundation is an independent, nonprofi t grant-making organization. For more than half a century it has worked with courageous people on the frontlines of social change worldwide, guided by its mission to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement. With headquarters in New York, the foundation has offi ces in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. All rights reserved. Parts of this summary may be quoted or used as long as the authors and Movement Strategy Center are duly recognized. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted for commercial purpose without prior permission. SUGGESTED CITATION: Zimmerman, K., Miao, V. (2009). Fertile Ground: Women Organizing at the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Reproductive Justice. Oakland, CA: Movement Strategy Center. For information about ordering any of our publications, visit www.movementstrategy.org or contact: Movement Strategy Center 1611 Telegraph Ave., Suite 510 Oakland, CA 94612 Ph. -

New Orleans, Louisiana Philanthropy: Yes

Name in English: Harry Lee Name in Chinese: 朱家祥 Name in Pinyin: Zhū Jiaxiáng Gender: Male Birth Year: 1932-2007 Birth Place: New Orleans, Louisiana Philanthropy: Yes Profession: Sheriff, Federal Judge, Attorney, Air Force Officer Education: B.S., Geology, 1956, Louisiana State University; J.D., 1967, Loyola University Law School Awards: 1983, AMVETS Silver Helmet Americanism Award; 1998, National Conference of Community and Justice’s first annual Founder’s Award; 1998, Award from the Foundation for Improvement of Justice; 2000, Honorary Doctor of Law, University of New Haven; 2001, Louisiana Political Hall of Fame (one of only four sheriffs ever inducted) Contributions: Harry Lee was born on August 27, 1932, in the back of his family’s laundry business in New Orleans, Louisiana. Like many children of working-class Chinese immigrants born during the Great Depression, he and his eight siblings worked in the family-owned laundry and restaurant while attending school. One of his younger sisters, Margaret, in 1964, became Playboy’s first Asian-American Playmate and centerfold (under the name China Lee). Hailing from a state where Asians comprise only 1.4% of the population, Harry Lee would become one of Louisiana’s most beloved politicians and its most outspoken and controversial law-enforcement official. Lee’s love of politics began at age 12, when, despite his minority status, he would be elected to one student office after another by defeating white classmates. After graduating from Louisiana State University and serving in the U.S. Air Force, Lee returned to Louisiana in 1959 to pursue a career in politics. -

2018 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE CONCURRENT

2018 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 31 BY SENATORS ALARIO, MARTINY, ALLAIN, APPEL, BARROW, BISHOP, BOUDREAUX, CARTER, CHABERT, CLAITOR, COLOMB, CORTEZ, DONAHUE, ERDEY, FANNIN, GATTI, HEWITT, JOHNS, LAFLEUR, LAMBERT, LONG, LUNEAU, MILKOVICH, MILLS, MIZELL, MORRELL, MORRISH, PEACOCK, PERRY, PETERSON, PRICE, RISER, GARY SMITH, JOHN SMITH, TARVER, THOMPSON, WALSWORTH, WARD AND WHITE AND REPRESENTATIVES ABRAHAM, ABRAMSON, AMEDEE, ANDERS, ARMES, BACALA, BAGLEY, BAGNERIS, BARRAS, BERTHELOT, BILLIOT, BISHOP, BOUIE, BRASS, CHAD BROWN, TERRY BROWN, CARMODY, CARPENTER, GARY CARTER, ROBBY CARTER, STEVE CARTER, CHANEY, CONNICK, COUSSAN, COX, CREWS, CROMER, DANAHAY, DAVIS, DEVILLIER, DWIGHT, EDMONDS, EMERSON, FALCONER, FOIL, FRANKLIN, GAINES, GAROFALO, GISCLAIR, GLOVER, GUINN, HALL, JIMMY HARRIS, LANCE HARRIS, HAVARD, HAZEL, HENRY, HENSGENS, HILFERTY, HILL, HODGES, HOFFMANN, HOLLIS, HORTON, HOWARD, HUNTER, HUVAL, IVEY, JACKSON, JAMES, JEFFERSON, JENKINS, JOHNSON, JONES, JORDAN, NANCY LANDRY, TERRY LANDRY, LEBAS, LEGER, LEOPOLD, LYONS, MACK, MAGEE, MARCELLE, MARINO, MCFARLAND, MIGUEZ, DUSTIN MILLER, GREGORY MILLER, MORENO, JAY MORRIS, JIM MORRIS, NORTON, PEARSON, PIERRE, POPE, PUGH, PYLANT, REYNOLDS, RICHARD, SCHEXNAYDER, SEABAUGH, SHADOIN, SIMON, SMITH, STAGNI, STEFANSKI, STOKES, TALBOT, THIBAUT, THOMAS, WHITE, WRIGHT AND ZERINGUE A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To commend, posthumously, former Jefferson Parish Sheriff Harry Lee for his extraordinary life and contributions to Jefferson Parish and the state of Louisiana. WHEREAS, it -

1 Record Group 1 Judicial Records of the French

RECORD GROUP 1 JUDICIAL RECORDS OF THE FRENCH SUPERIOR COUNCIL Acc. #'s 1848, 1867 1714-1769, n.d. 108 ln. ft (216 boxes); 8 oversize boxes These criminal and civil records, which comprise the heart of the museum’s manuscript collection, are an invaluable source for researching Louisiana’s colonial history. They record the social, political and economic lives of rich and poor, female and male, slave and free, African, Native, European and American colonials. Although the majority of the cases deal with attempts by creditors to recover unpaid debts, the colonial collection includes many successions. These documents often contain a wealth of biographical information concerning Louisiana’s colonial inhabitants. Estate inventories, records of commercial transactions, correspondence and copies of wills, marriage contracts and baptismal, marriage and burial records may be included in a succession document. The colonial document collection includes petitions by slaves requesting manumission, applications by merchants for licenses to conduct business, requests by ship captains for absolution from responsibility for cargo lost at sea, and requests by traders for permission to conduct business in Europe, the West Indies and British colonies in North America **************************************************************************** RECORD GROUP 2 SPANISH JUDICIAL RECORDS Acc. # 1849.1; 1867; 7243 Acc. # 1849.2 = playing cards, 17790402202 Acc. # 1849.3 = 1799060301 1769-1803 190.5 ln. ft (381 boxes); 2 oversize boxes Like the judicial records from the French period, but with more details given, the Spanish records show the life of all of the colony. In addition, during the Spanish period many slaves of Indian 1 ancestry petitioned government authorities for their freedom. -

Membership in the Louisiana House of Representatives

MEMBERSHIP IN THE LOUISIANA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 1812 - 2024 Revised – July 28, 2021 David R. Poynter Legislative Research Library Louisiana House of Representatives 1 2 PREFACE This publication is a result of research largely drawn from Journals of the Louisiana House of Representatives and Annual Reports of the Louisiana Secretary of State. Other information was obtained from the book, A Look at Louisiana's First Century: 1804-1903, by Leroy Willie, and used with the author's permission. The David R. Poynter Legislative Research Library also maintains a database of House of Representatives membership from 1900 to the present at http://drplibrary.legis.la.gov . In addition to the information included in this biographical listing the database includes death dates when known, district numbers, links to resolutions honoring a representative, citations to resolutions prior to their availability on the legislative website, committee membership, and photographs. The database is an ongoing project and more information is included for recent years. Early research reveals that the term county is interchanged with parish in many sources until 1815. In 1805 the Territory of Orleans was divided into counties. By 1807 an act was passed that divided the Orleans Territory into parishes as well. The counties were not abolished by the act. Both terms were used at the same time until 1845, when a new constitution was adopted and the term "parish" was used as the official political subdivision. The legislature was elected every two years until 1880, when a sitting legislature was elected every four years thereafter. (See the chart near the end of this document.) The War of 1812 started in June of 1812 and continued until a peace treaty in December of 1814. -

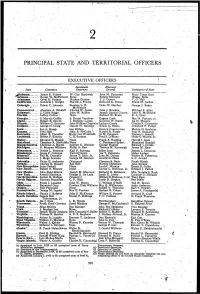

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M.