Effective Pollination of Aeschynanthus Acuminatus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwest Guangdong, 28 April to 7 May 1998

Report of Rapid Biodiversity Assessments at Qixingkeng Nature Reserve, Southwest Guangdong, 29 April to 1 May and 24 November to 1 December, 1998 Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden in collaboration with Guangdong Provincial Forestry Department South China Institute of Botany South China Agricultural University South China Normal University Xinyang Teachers’ College January 2002 South China Biodiversity Survey Report Series: No. 4 (Online Simplified Version) Report of Rapid Biodiversity Assessments at Qixingkeng Nature Reserve, Southwest Guangdong, 29 April to 1 May and 24 November to 1 December, 1998 Editors John R. Fellowes, Michael W.N. Lau, Billy C.H. Hau, Ng Sai-Chit and Bosco P.L. Chan Contributors Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden: Bosco P.L. Chan (BC) Lawrence K.C. Chau (LC) John R. Fellowes (JRF) Billy C.H. Hau (BH) Michael W.N. Lau (ML) Lee Kwok Shing (LKS) Ng Sai-Chit (NSC) Graham T. Reels (GTR) Gloria L.P. Siu (GS) South China Institute of Botany: Chen Binghui (CBH) Deng Yunfei (DYF) Wang Ruijiang (WRJ) South China Agricultural University: Xiao Mianyuan (XMY) South China Normal University: Chen Xianglin (CXL) Li Zhenchang (LZC) Xinyang Teachers’ College: Li Hongjing (LHJ) Voluntary consultants: Guillaume de Rougemont (GDR) Keith Wilson (KW) Background The present report details the findings of two field trips in Southwest Guangdong by members of Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden (KFBG) in Hong Kong and their colleagues, as part of KFBG's South China Biodiversity Conservation Programme. The overall aim of the programme is to minimise the loss of forest biodiversity in the region, and the emphasis in the first three years is on gathering up-to-date information on the distribution and status of fauna and flora. -

Some Kinangop Sunbirds

SOME KINANGOP SUNBIRDS. By SIR CHARLES F. BELCHER. Four species of Sunbird commonly occur in the valley of the gularis,Chania atSharpe,South Kinangop.the KenyaTheseMalachiteare NectariniaSunbird;famosaNectariniaaenei• tacazze (Stanley), the Tacazze Sunbird; Drepanorhynchus reiche• nowi, Fischer, the Golden-winged Sunbird; and Cinnyris medio• cris mediocris, Shelley,. the Kenya Double-collared Sunbird. The association of these four species was observed long ago by Sir Frederick Jackson (vide what is unquestionably an original note. of his in the recently-published "Birds of Kenya and Uganda," edited by W. L. Sclater, at page 1342 in the third volume). So far, during a residence of nearly twelve months on the Kinangop, I have not met with the Bronzy Sunbird (N. kili• mensis kilimensis, Shelley) which might be expected to occur and has been taken as near as Limoru at an altitude not more than 1,500 feet below us, but which I think must be regarded as definitely a: bird of, in these parts at least, lower altitudes than the Kinangop Plateau; and another species not yet noted is the Scarlet-tufted Malachite Sunbird (Nectarinia johnstoni johnstoni, Shelley) which though quoted by Sclater as occurring on Kilima• njaro and Kenya Mountains only, certainly is found as well on the higher parts of the Aberdares; and, as I am informed by Dr. van Someren, has once been noted on Major Ward's estate which is at much the same level as the main run of the Kinangop close in to the mountain, i.e. about 8,500 feet above the sea. It woold doubtless be an occasional visitor only from the higher levels. -

Printable PDF Format

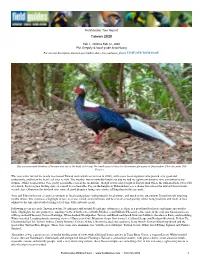

Field Guides Tour Report Taiwan 2020 Feb 1, 2020 to Feb 12, 2020 Phil Gregory & local guide Arco Huang For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. This gorgeous male Swinhoe's Pheasant was one of the birds of the trip! We found a pair of these lovely endemic pheasants at Dasyueshan. Photo by guide Phil Gregory. This was a first run for the newly reactivated Taiwan tour (which we last ran in 2006), with a new local organizer who proved very good and enthusiastic, and knew the best local sites to visit. The weather was remarkably kind to us and we had no significant daytime rain, somewhat to my surprise, whilst temperatures were pretty reasonable even in the mountains- though it was cold at night at Dasyueshan where the unheated hotel was a bit of a shock, but in a great birding spot, so overall it was bearable. Fog on the heights of Hohuanshan was a shame but at least the mid and lower levels stayed clear. Otherwise the lowland sites were all good despite it being very windy at Hengchun in the far south. Arco and I decided to use a varied assortment of local eating places with primarily local menus, and much to my amazement I found myself enjoying noodle dishes. The food was a highlight in fact, as it was varied, often delicious and best of all served quickly whilst being both hot and fresh. A nice adjunct to the trip, and avoided losing lots of time with elaborate meals. -

Biogeography and Biotic Assembly of Indo-Pacific Corvoid Passerine Birds

ES48CH11-Jonsson ARI 9 October 2017 7:38 Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics Biogeography and Biotic Assembly of Indo-Pacific Corvoid Passerine Birds Knud Andreas Jønsson,1 Michael Krabbe Borregaard,1 Daniel Wisbech Carstensen,1 Louis A. Hansen,1 Jonathan D. Kennedy,1 Antonin Machac,1 Petter Zahl Marki,1,2 Jon Fjeldsa˚,1 and Carsten Rahbek1,3 1Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, 0318 Oslo, Norway 3Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Ascot SL5 7PY, United Kingdom Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017. 48:231–53 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on Corvides, diversity assembly, evolution, island biogeography, Wallacea August 11, 2017 The Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Abstract Systematics is online at ecolsys.annualreviews.org The archipelagos that form the transition between Asia and Australia were https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316- immortalized by Alfred Russel Wallace’s observations on the connections 022813 between geography and animal distributions, which he summarized in Copyright c 2017 by Annual Reviews. what became the first major modern biogeographic synthesis. Wallace All rights reserved traveled the island region for eight years, during which he noted the marked Access provided by Copenhagen University on 11/19/17. For personal use only. faunal discontinuity across what has later become known as Wallace’s Line. Wallace was intrigued by the bewildering diversity and distribution of Annu. -

Bird Diversity in Northern Myanmar and Conservation Implications

ZOOLOGICAL RESEARCH Bird diversity in northern Myanmar and conservation implications Ming-Xia Zhang1,2, Myint Kyaw3, Guo-Gang Li1,2, Jiang-Bo Zhao4, Xiang-Le Zeng5, Kyaw Swa3, Rui-Chang Quan1,2,* 1 Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yezin Nay Pyi Taw 05282, Myanmar 2 Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla Yunnan 666303, China 3 Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary Offices, Putao Kachin 01051, Myanmar 4 Science Communication and Training Department, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla Yunnan 666303, China 5 Yingjiang Bird Watching Society, Yingjiang Yunnan 679300, China ABSTRACT Since the 1990s, several bird surveys had been carried out in the Putao area (Rappole et al, 2011). Under the leadership of We conducted four bird biodiversity surveys in the the Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division (NWCD) of the Putao area of northern Myanmar from 2015 to 2017. Myanmar Forestry Ministry, two expeditions were launched in Combined with anecdotal information collected 1997–1998 (Aung & Oo, 1999) and 2001–2009 (Rappole et al., between 2012 and 2015, we recorded 319 bird 2011), providing the most detailed inventory of local avian species, including two species (Arborophila mandellii diversity thus far. 1 and Lanius sphenocercus) previously unrecorded in Between December 2015 and May 2017, the Southeast Asia Myanmar. Bulbuls (Pycnonotidae), babblers (Timaliidae), Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences pigeons and doves (Columbidae), and pheasants (CAS-SEABRI), Forest Research Institute (FRI) of Myanmar, and partridges (Phasianidae) were the most Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary (HPWS), and Hkakabo Razi abundant groups of birds recorded. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Systematic Notes on Asian Birds. 28

ZV-340 179-190 | 28 04-01-2007 08:56 Pagina 179 Systematic notes on Asian birds. 28. Taxonomic comments on some south and south-east Asian members of the family Nectariniidae C.F. Mann Mann, C.F. Systematic notes on Asian birds. 28. Taxonomic comments on some south and south-east Asian members of the family Nectariniidae. Zool. Verh. Leiden 340, 27.xii.2002: 179-189.— ISSN 0024-1652/ISBN 90-73239-84-2. Clive F. Mann, 53 Sutton Lane South, London W4 3JR, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]). Keywords: Asia; Nectariniidae; taxonomy. Certain taxonomic changes made by Cheke & Mann (2001) are here explained and justified. Dicaeum haematostictum Sharpe, 1876, is split from D. australe (Hermann, 1783). D. aeruginosum Bourns & Worcester, 1894 is merged into D. agile (Tickell, 1833). The genus Chalcoparia Cabanis, 1851, is re-estab- lished for (Motacilla) singalensis Gmelin, 1788. The taxon Leptocoma sperata marinduquensis (duPont, 1971), is shown to be based on a specimen of Aethopyga siparaja magnifica Sharpe, 1876. Aethopyga vigor- sii (Sykes, 1832) is split from A. siparaja (Raffles, 1822). Cheke & Mann (op. cit.) mistakenly omitted two forms, Anthreptes malacensis erixanthus Oberholser, 1932 and Arachnothera longirostra zarhina Ober- holser, 1912. Five subspecies are removed from Aethopyga shelleyi Sharpe, 1876 to create the polytypic A. bella, Tweeddale, 1877. The Arachnothera affinis (Horsfield, 1822)/modesta (Eyton, 1839)/everetti (Sharpe, 1893) complex is re-evaluated in the light of the revision by Davison in Smythies (1999). Introduction In a recent publication (Cheke & Mann, 2001) some taxonomic changes were made to members of this family occurring in Asia. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Aeschynanthus Pulcher Lipstick Plant LIPSTICK PLANT

The Gardener’s Resource 435 W. Glenside Ave. Since 1943 Glenside, PA 19038 215-887-7500 Aeschynanthus pulcher Lipstick Plant LIPSTICK PLANT Lipstick plants are easy indoor flowering houseplants that when given the right amount of light and water, they produce numerous red or orange small tubular flowers that resemble a tube of lipstick. Not only are the flowers colorful, the leaves can be light green, dark green or green and maroon. Light: The Lipstick vine will not bloom without adequate light. They require very bright, indirect light. Avoid placing this plant in full shade or full sun. Direct sun will burn the leaves. The plant needs bright light for a portion of the day, but not all day long. Water: If you allow the top 25% of the soil to dry out before watering, this plant will flower more frequently and more abundant. If the leaves appear soft and shriveled, give it more water. These plants will also lose green leaves TIPS: when over-watered. • Lipstick plants like warm temperatures between 75-85°F. : Fertilizer every other week in the Fertilizing • Prefers high humidity, but will do well in Spring and Summer and only monthly in the basic household humidity too. Fall and Winter with a houseplant food high in • Trim the long vines to prevent the plant phosphorous. Always dilute the fertilizer to ½ from becoming thin and straggly. the recommended strength. • Lipstick Plants are Non-Poisonous. • Keep a lipstick plant in a small pot will help it produce more flowers. When put into a large container, instead of producing flowers it grows more leaves. -

Temporal and Spatial Origin of Gesneriaceae in the New World Inferred from Plastid DNA Sequences

bs_bs_banner Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2013, 171, 61–79. With 3 figures Temporal and spatial origin of Gesneriaceae in the New World inferred from plastid DNA sequences MATHIEU PERRET1*, ALAIN CHAUTEMS1, ANDRÉA ONOFRE DE ARAUJO2 and NICOLAS SALAMIN3,4 1Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève, Ch. de l’Impératrice 1, CH-1292 Chambésy, Switzerland 2Centro de Ciências Naturais e Humanas, Universidade Federal do ABC, Rua Santa Adélia, 166, Bairro Bangu, Santo André, Brazil 3Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland 4Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Quartier Sorge, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Received 15 December 2011; revised 3 July 2012; accepted for publication 18 August 2012 Gesneriaceae are represented in the New World (NW) by a major clade (c. 1000 species) currently recognized as subfamily Gesnerioideae. Radiation of this group occurred in all biomes of tropical America and was accompanied by extensive phenotypic and ecological diversification. Here we performed phylogenetic analyses using DNA sequences from three plastid loci to reconstruct the evolutionary history of Gesnerioideae and to investigate its relationship with other lineages of Gesneriaceae and Lamiales. Our molecular data confirm the inclusion of the South Pacific Coronanthereae and the Old World (OW) monotypic genus Titanotrichum in Gesnerioideae and the sister-group relationship of this subfamily to the rest of the OW Gesneriaceae. Calceolariaceae and the NW genera Peltanthera and Sanango appeared successively sister to Gesneriaceae, whereas Cubitanthus, which has been previously assigned to Gesneriaceae, is shown to be related to Linderniaceae. Based on molecular dating and biogeographical reconstruction analyses, we suggest that ancestors of Gesneriaceae originated in South America during the Late Cretaceous. -

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-Eaters, Babblers, and a Whole Lot More

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-eaters, Babblers, and a whole lot more A Tropical Birding Set Departure July 1-16, 2018 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY Borneo lies in one of the biologically richest areas on Earth – the Asian equivalent of Costa Rica or Ecuador. It holds many widespread Asian birds, plus a diverse set of birds that are restricted to the Sunda region (southern Thailand, peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo), and dozens of its own endemic birds and mammals. For family listing birders, the Bornean Bristlehead, which makes up its own family, and is endemic to the island, is the top target. For most other visitors, Orangutan, the only great ape found in Asia, is the creature that they most want to see. But those two species just hint at the wonders held by this mysterious island, which is rich in bulbuls, babblers, treeshrews, squirrels, kingfishers, hornbills, pittas, and much more. Although there has been rampant environmental destruction on Borneo, mainly due to the creation of oil palm plantations, there are still extensive forested areas left, and the Malaysian state of Sabah, at the northern end of the island, seems to be trying hard to preserve its biological heritage. Ecotourism is a big part of this conservation effort, and Sabah has developed an excellent tourist infrastructure, with comfortable lodges, efficient transport companies, many protected areas, and decent roads and airports. So with good infrastructure, and remarkable biological diversity, including many marquee species like Orangutan, several pittas and a whole Borneo: Bristleheads and Broadbills July 1-16, 2018 range of hornbills, Sabah stands out as one of the most attractive destinations on Earth for a travelling birder or naturalist. -

Thailand Highlights 14Th to 26Th November 2019 (13 Days)

Thailand Highlights 14th to 26th November 2019 (13 days) Trip Report Siamese Fireback by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland Trip Report – RBL Thailand - Highlights 2019 2 Tour Summary Thailand has been known as a top tourist destination for quite some time. Foreigners and Ex-pats flock there for the beautiful scenery, great infrastructure, and delicious cuisine among other cultural aspects. For birders, it has recently caught up to big names like Borneo and Malaysia, in terms of respect for the avian delights it holds for visitors. Our twelve-day Highlights Tour to Thailand set out to sample a bit of the best of every major habitat type in the country, with a slight focus on the lush montane forests that hold most of the country’s specialty bird species. The tour began in Bangkok, a bustling metropolis of winding narrow roads, flyovers, towering apartment buildings, and seemingly endless people. Despite the density and throng of humanity, many of the participants on the tour were able to enjoy a Crested Goshawk flight by Forrest Rowland lovely day’s visit to the Grand Palace and historic center of Bangkok, including a fun boat ride passing by several temples. A few early arrivals also had time to bird some of the urban park settings, even picking up a species or two we did not see on the Main Tour. For most, the tour began in earnest on November 15th, with our day tour of the salt pans, mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves of the famed Pak Thale Shore bird Project, and Laem Phak Bia mangroves.