„‚ Management by Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manager Cascade, Edit, Or Discontinue Goal(S) in Workday

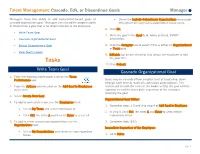

Talent Management: Cascade, Edit, or Discontinue Goals Manager Managers have the ability to add department-based goals or • Check the Include Subordinate Organizations to cascade cascade organization goal. Managers can also edit in-progress goals throughout all supervisory organization below yours. or discontinue a goal that is no longer relevant to the employee. 6. Click OK. • Write Team Goal 7. Write the goal in the Goal field. Add a detailed, SMART • Cascade Organizational Goal description. • Edit or Discontinue a Goal 8. Click the Category box to select if this is either an Organizational or Team goal. • View Team’s Goals 9. Editable will be pre-selected. This allows the employee to edit Tasks the goal title. 10. Click Submit. Write Team Goal Cascade Organizational Goal 1. From the Workday home page, click on the Team Performance app. Goals may be cascaded from a higher level of leadership, down through each level to reach all supervisory organizations. This 2. From the Actions column, click on the Add Goal to Employees section will include the steps of the leader writing the goal and the menu item. approval step of the immediate supervisor of the employee receiving the goal. 3. Select Create New Goal. Organizational Goal Writer: 4. To add to immediate team, use the Employees field: 1. Complete steps 1-3 and skip step 4 of Add Goal to Employee. • Select My Team and select individuals or 2. In step 5, click Ctrl, the letter A and Enter to select entire • Click Ctrl, the letter A and then hit Enter to select all. -

Billboard.Com “Finesse” Hits a New High After Cardi B Hopped on the Track’S Remix, Which Arrived on Jan

GRAMMYS 2018 ‘You don’t get to un-have this moment’ LORDE on a historic Grammys race, her album of the year nod and the #MeToo movement PLUS Rapsody’s underground takeover and critics’ predictions for the Big Four categories January 20, 2018 | billboard.com “Finesse” hits a new high after Cardi B hopped on the track’s remix, which arrived on Jan. 4. COURTESY OF ATLANTIC RECORDS ATLANTIC OF COURTESY Bruno Mars And Cardi B Title CERTIFICATION Artist osition 2 Weeks Ago Peak P ‘Finesse’ Last Week This Week PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL Weeks On Chart #1 111 6 WK S Perfect 2 Ed Sheeran 120 Their Way Up W.HICKS,E.SHEERAN (E.C.SHEERAN) ATLANTIC sic, sales data as compiled by Nielsen Music and streaming activity data by online music sources tracked by Nielsen Music. tracked sic, activity data by online music sources sales data as compiled by Nielsen Music and streaming Havana 2 Camila Cabello Feat. Young Thug the first time. See Charts Legend on billboard.com/biz for complete rules and explanations. © 2018, Prometheus Global Media, LLC and Nielsen Music, Inc. Global Media, LLC All rights reserved. © 2018, Prometheus for complete rules and explanations. the first time. See Charts on billboard.com/biz Legend 3 2 2 222 FRANK DUKES (K.C.CABELLO,J.L.WILLIAMS,A.FEENY,B.T.HAZZARD,A.TAMPOSI, The Hot 100 B.LEE,A.WOTMAN,P.L.WILLIAMS,L.BELL,R.L.AYALA RODRIGUEZ,K.GUNESBERK) SYCO/EPIC DG AG SG Finesse Bruno Mars & Cardi B - 35 3 32 RUNO MARS AND CARDI B achieve the career-opening feat, SHAMPOO PRESS & CURL,STEREOTYPES (BRUNO MARS,P.M.LAWRENCE II, C.B.BROWN,J.E.FAUNTLEROY II,J.YIP,R.ROMULUS,J.REEVES,R.C.MCCULLOUGH II) ATLANTIC bring new jack swing and the second male; Lionel Richie back to the top 10 of the landed at least three from each of his 2 3 4 Rockstar 2 Post Malone Feat. -

Basic Understanding on Supply Chain in Management by Eliot Messiah K

Global Journal of Management and Business Research: A Administration and Management Volume 17 Issue 3 Version 1.0 Year 2017 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 Basic Understanding on Supply Chain in Management By Eliot Messiah K. Afli & Dr. Jin Mei Lanzhou Jiaotong University Abstract- There has been some few definitions about what effective management of an organization should be, the structures to put in place so as to get the best administration of the organization. This study looks at the supply chain in the direction of an organization, its importance, and design. This study, however, concluded that it is useful for every business to have a supply chain in the organization since it does coordinate the people and activities within including those outside the organization and that it also maximize profit by eliminating unnecessary cost. Keywords: supply chain system, supply chain design, innovation, management. GJMBR-A Classification: JEL Code: M19 BasicUnderstandingonSupplyChaininManag ement Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2017. Eliot Messiah K. Afli & Dr. Jin Mei. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Basic Understanding on Supply Chain in Management Eliot Messiah K. Afli α & Dr. Jin Mei σ Abstract- There has been some few definitions about what Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933) said: effective management of an organization should be, the "management is to get things done through people." structures to put in place so as to get the best administration She described management to be a philosophy. -

Personal Goals, Life Meaning, and Virtue: Wellsprings of a Positive Life

5 PERSONAL GOALS, LIFE MEANING, AND VIRTUE: WELLSPRINGS OF A POSITIVE LIFE ROBERT A. EMMONS Nothing is so insufferable to man as to be completely at rest, without passions, without business, without diversion, without effort. Then he feels his nothingness, his forlornness, his insufficiency, his weakness, his emptiness. (Pascal, The Pensees, 1660/1950, p. 57). As far as we know humans are the only meaning-seeking species on the planet. Meaning-making is an activity that is distinctly human, a function of how the human brain is organized. The many ways in which humans conceptualize, create, and search for meaning has become a recent focus of behavioral science research on quality of life and subjective well-being. This chapter will review the recent literature on meaning-making in the context of personal goals and life purpose. My intention will be to document how meaningful living, expressed as the pursuit of personally significant goals, contributes to positive experience and to a positive life. THE CENTRALITY OF GOALS IN HUMAN FUNCTIONING Since the mid-1980s, considerable progress has been made in under- standing how goals contribute to long-term levels of well-being. Goals have been identified as key integrative and analytic units in the study of human Preparation of this chapter was supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. I would like to express my gratitude to Corey Lee Keyes and Jon Haidt for the helpful comments on an earlier draft of this chapter. 105 motivation (see Austin & Vancouver, 1996; Karoly, 1999, for reviews). The driving concern has been to understand how personal goals are related to long-term levels of happiness and life satisfaction and how ultimately to use this knowledge in a way that might optimize human well- being. -

Management by Objectives: Advantages, Problems, Implications for Community Colleges

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 057 792 JC 720 028 AUTHOR Collins, Robert W. TITLE Management by Objectives: Advantages, Problems, Implications for Community Colleges. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 20p.; Seminar paper EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Administrative Principles; Decision Making; *Educational Administration; *Junior Colleges; *Management; *Management Development; *Management Systems; Objectives ABSTRACT Not new in principle, management by objectives (MBO) focuses on the goals of an institution stated as end accomplishments. Community college administrators have been attracted by the reputed benefits of MBO: increased productivity, improved planning, maximized profits, objective managerial evaluation, and improved participant morale. This paper summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of MBO learned and reported from business and industry. Problems encountered in MBO programs include: lack of total organizational commitment, lack of prerequisites to implementation, failpre to integrate individual and organizational goals, overemph sis on measurable goal attainment, and inadequacies in performance a praisal. To be most effective in community colleges, MBO must have the total backing of board members and the president. Furthermore, the school must be prepared to commit extra time to implement MBO. The major determinant of the success or failure of MBO type programs is largely a result of its acceptance by users. (IA1 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE Of'FICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT POINTS 0:' VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DC NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL. -FFICE OF EDU- "CATION.POSITION OR POLICY. CNJ MANAGEMENT BY OBJECTIVES: ADVANTAGES, PROBLEMS, IMPLICATIONS FOR COMMUNITY COLLEGES BY: Robert W. -

Unlisted Properties: an Exploration in Solo Performance

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Unlisted Properties: An Exploration in Solo Performance Jason Smith Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Jason Edward Smith and Lauren Marinelli White, 2008 All Rights Reserved UNLISTED PROPERTIES: AN EXPLORATION IN SOLO PERFORMANCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by LAUREN MARINELLI WHITE B.A., Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2002 and JASON EDWARD SMITH B.A., The College of William and Mary, 2004 Director: DR. TAWNYA PETTIFORD-WATES ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ACTING AND DIRECTING, THEATRE Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May, 2008 ii Acknowledgement Lauren and Jase would first and foremost like to thank our mentor, Dr. Tawnya Pettiford-Wates, for her unwavering support, encouragement, friendship and tenacious loyalty. Without her guidance, neither this project nor our journeys in this program would have been as fulfilling and enriching as we will always remember them to be. In addition, we would like to thank Dr. Noreen Barnes and David McLain, MFA for their unique perspectives and valuable guidance. We would also like to thank the creative talents of those involved with the development of this project: Melissa Carroll-Jackson, Jenna Ferre, Ron Keller, Kevin McGranahan, Carol Piersol, Tommy Pruitt, Kay Stone, and Shanea N. -

Program Overview Training Objectives Time Management

Time Management Program Overview At times you may hear people getting stressed and complaining that there is no balance in their lives. They feel that they are unable to deliver what they promise; they end up disappointing colleagues and are constantly pressured to prove themselves as they are slipping on commitments. Perhaps! They aren’t doing well managing their time. Making sure you deliver what’s promised to build personal and professional credibility should be reason enough to learn how to manage time. The need for exercising conscious control over the amount of time spent on specific activities, leading to enhancement of effectiveness, efficiency or productivity drives the need for building skills on Time management. So, how does one manage time? Planning, Prioritizing, Scheduling and Monitoring can be some methods that can be used to effectively manage one’s time. Knowing what to work on, when and how much time you have to finish the work makes you more focused and keeps you away from such activities which either you do not have to work on or can be worked on later. This focus on the work ensures that you get more quality work out. TCG’s program on Time Management is aimed at helping you Prioritize your work, Deliver quality work, Get more done in less time, Deliver what’s promised, Discipline you day and activities, Deliver more that you thought you could and more importantly, build immense credibility for yourself! Training Objectives Assess your personal Time Management style Manage time conflicts Learn to make timely decisions -

CREATE a PLANNING CULTURE Small Changes That Can Make a Big Impact on Your Operation’S Efficiency and Performance

leading thoughts / aug 2014 CREATE A PLANNING CULTURE Small changes that can make a big impact on your operation’s efficiency and performance. By Chuck Swain, Interactive Intelligence Pipeline Articles www.contactcenterpipeline.com Create a Planning Culture t’s no secret that personnel costs make up roughly two-thirds of contact center operating budgets. Getting the “right” number of staff in place is critical to ensure that your center can Imeet service goals and control costs. Yet one of the top missteps contact center leaders make is to deprioritize their strategic planning process in lieu of “running the contact center.” The day-to-day execution of your staffing plan is a very important part of delivering service in a contact center. How well you’re prepared for each interval of the day is a critical success factor that distinguishes good performance from chaos. By prioritizing contact center planning and investing in a workforce management (WFM) function, you can overcome staffing and Chuck Swain workload challenges, control agent stress and become proficient at maintaining a cost-efficient Interactive Intelligence environment. Plan to Plan A fundamental first step is to dedicate the right resources to planning. Supporting a WFM function must be a top priority! WFM’s planning role will coordinate much of what it takes to help leadership predict future events, which isn’t a “straight-line” undertaking. Your WFM team will be asked to compile mounds of data and turn it into something usable for capacity planning and scheduling against daily and intraday volume patterns. Expecting to “do more with less” by asking a contact center supervisor or manager to moonlight in the WFM role is a bad idea. -

Tips for Time Management Lisa Medoff, Ph.D

Tips for Time Management Lisa Medoff, Ph.D. Education Specialist Stanford School of Medicine [email protected] • Plan ahead and set a schedule o Be both strict and flexible: Work when you plan to do so, but be willing to substitute another high-priority task when you cannot focus on what you had planned to work on. o Include both free time (socializing and media use) and cushion time (extra hours for unpredicted circumstances) in your planned schedule. ! Try to avoid unscheduled social and media time as much as possible. ! Decide ahead of time who/what is worth breaking your schedule for and who/what is not. ! Schedule a few hours for catching up once a week. If you are all caught up, use this time to reward yourself with a break (or, if you are really motivated, use it to get ahead for next week!). o Be accountable to someone. ! Share your schedule with a friend and ask him/her to check in with you later to make sure you followed it. ! Know when you need to be held the most accountable. Early mornings? Evenings? Arrange to meet someone at a designated time to help keep you on track. • Be realistic: As you adjust to a new study schedule, keep track of how long you estimate a task will take and compare it to how long it actually takes. Also keep track of which ways of studying are the most efficient and which ones take up time, but do not 1 seem to add much value. Finally, keep track of ways that you wasted your time. -

A Family Christmas Devotional

A FAMILY CHRISTMAS DEVOTIONAL 1 A devotional focused on the events of 2020 2 What a year … While it probably seems a little cliche at this point, we recognize that 2020 has been a year unlike any in recent memory. From a global pandemic, to civic unrest, to an extremely contentious election season, it has often seemed like Hell must be throwing everything at us (including the kitchen sink). We are all worn and weary, and in need of some rest and hope. Unfortunately, the holidays are often anything but restful, aren’t they? If anything, the days are filled with nonstop to-do’s, activities, more stress, and the rush to “fit everything in.” For many of us, it can feel like we’re just barely making it to New Year’s alive. And in the midst of the frenzy and stress, we often miss what this season is truly all about. Does the true meaning of Christmas even matter anymore? Are we just running around all month for silly, old-fashioned traditions? Most of us probably know that all of this began with a story in the Bible, but how do we know we can even trust that anymore? And if we can’t trust it, then why are we adding more stress and busyness at the end of a long, stressful year? If you’ve ever wondered in your own spirit if all of this really matters, don’t worry; you’re not alone! All of the questions are understandable – especially this year – but especially because of how stressful this year has been, we want to help point you and your loved ones back to the true meaning of Christmas. -

Formal Aspects of Organization Structure; A

FORMAL ASPECTS OF ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE; A CASE STUDY OF A STATE OWNED INSURANCE COMPANY by Cecilio Augusto Farias Berndsen A Dissertation Presented to the FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Public Administration) June 1975 UMI Number: DP308/I5 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertalien RùibhsMng UMI DP30845 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY PARK LOS ANGELES. CALIFORNIA 90007 PA.D. Pu VS" This dissertation, written by C ecilio Agusto Farias Berndsen ^ 'ASYA'S. i5 under the direction A.!?.....of Dissertation Com mittee, and approved by all its members, has been presented to and accepted by The Graduate School, in partial fulfillment of requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY D ea n DISSERTATION COMMITTEE hatrman TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF T A B L E S ................................... iv LIST OF F I G U R E S ................................. vi Œiapter I. INTRODUCTION............................... 1 Purpose and General Background Problem Area Research Question Importance of the Subject Towards a Definition of Formal Organization Structure Organization of the Remainder of the Dissertation II. -

Marketing IS Management: the Wisdom of Peter Drucker

J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. (2009) 37:20–27 DOI 10.1007/s11747-008-0102-4 CONCEPTUAL/THEORETICAL PAPER Marketing IS management: The wisdom of Peter Drucker Frederick E. Webster Jr. Received: 5 June 2008 /Accepted: 10 June 2008 /Published online: 9 July 2008 # Academy of Marketing Science 2008 Peter F. Drucker is widely regarded as one of the last business activity and the role of management within that century's most influential management thinkers. He is activity. He stressed the necessity of principles, values, and generally acknowledged to be the father of the modern theory as guides for management action. His focus was marketing management concept (Day 1990: 18; Drucker always on management in general, not marketing per se, 1954:34–48; Webster 2002: 1) although he denied that he with an understanding of customers’ ever-changing needs, was expert on marketing. The only article by Drucker wants, and preferences as the driving force for business published in Journal of Marketing was a transcript of his success. Parlin Memorial Lecture (dealing with marketing and It was Peter Drucker who first offered a distinct view of economic development) to the Philadelphia chapter of the marketing as the central management discipline by assert- American Marketing Association in 1957, in which he said, ing that: “I am not competent to speak about marketing…as a There is only one valid definition of business purpose: functional discipline of business.” (Drucker 1958: 253) to create a customer… Because it is its purpose to Despite this disclaimer, his thinking and writing had create a customer, any business enterprise has two— profound impact on the field of marketing management as and only these two—basic functions: marketing and the Marketing Concept became the central idea of market- innovation.