Downloadable Data Files, and Links to Other Sites Likely to Be of Interest to Committee Members

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiscal Impact of Suntrust Park and the Battery Atlanta on Cobb County

Fiscal Impact of SunTrust Park and The Battery Atlanta on Cobb County Prepared on behalf of: Copyright © 2018 All Rights Reserved Georgia Tech Research Corporation Atlanta, GA 30332 September 2018 Introduction Historically, professional sports stadiums were privately owned by the sports teams that played within them. Early exceptions to this were the Los Angeles Coliseum, Chicago’s Soldier Field, and Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium. However, all three of these facilities were built with the intention of attracting the Olympic Games.1 And then, in 1953, the Braves changed the paradigm when they re-located from Boston to Milwaukee to play in Milwaukee County Stadium which was built entirely with public funds.2 That move began the new modern era of publicly funded stadiums. Since 1953, hundreds of new sports facilities have been built across the country using billions of dollars of taxpayer money. Strategies used to justify these expenditures tend to fall into two categories – tangible economic benefits to the community and/or intangible social benefits including publicity, community self-esteem or improved “quality of life.”3 In fact, when employed by a local government, the author of this report – as many others have done before and since − used similar justifications around a new sports stadium in Gwinnett County.4 However, years of academic research into the subject suggests that the economic impact that accrues to a community solely from a new stadium – measured in terms of jobs and income − are usually inadequate to justify the public investment.5 Further, public financial benefits including new revenues from taxes and/or other fees rarely offset the public cost of the facility. -

Top Sluggers and Their Home Run Breakdowns

Best of Baseball Prospectus: 1996-2011 Part 1: Offense 6 APRIL 22, 2004 : http://bbp.cx/a/2795 HANK AARON'S HOME COOKING Top Sluggers and Their Home Run Breakdowns Jay Jaffe One of the qualities that makes baseball unique is its embrace of non-standard playing surfaces. Football fields and basketball courts are always the same length, but no two outfields are created equal. As Jay Jaffe explains via a look at Barry Bonds and the all-time home run leaderboard, a player’s home park can have a significant effect on how often he goes yard. It's been a couple of weeks since the 30th anniversary of Hank Aaron's historic 715th home run and the accompanying tributes, but Barry Bonds' exploits tend to keep the top of the all-time chart in the news. With homers in seven straight games and counting at this writing, Bonds has blown past Willie Mays at number three like the Say Hey Kid was standing still, which— congratulatory road trip aside—he has been, come to think of it. Baseball Prospectus' Dayn Perry penned an affectionate tribute to Aaron last week. In reviewing Hammerin' Hank's history, he notes that Aaron's superficially declining stats in 1968 (the Year of the Pitcher, not coincidentally) led him to consider retirement, but that historian Lee Allen reminded him of the milestones which lay ahead. Two years later, Aaron became the first black player to cross the 3,000 hit threshold, two months ahead of Mays. By then he was chasing 600 homers and climbing into some rarefied air among the top power hitters of all time. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

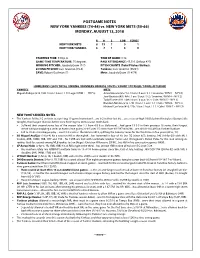

Post-Game Notes

POSTGAME NOTES NEW YORK YANKEES (74-44) vs. NEW YORK METS (50-66) MONDAY, AUGUST 13, 2018 R H E LOB SERIES NEW YORK METS 8 15 1 9 1 NEW YORK YANKEES 5 7 1 5 0 STARTING TIME: 7:09 p.m. TIME OF GAME: 3:18 GAME-TIME TEMPERATURE: 75 degrees PAID ATTENDANCE: 47,233 (Sellout #22) WINNING PITCHER: Jacob deGrom (7-7) PITCH COUNTS (Total Pitches/Strikes): LOSING PITCHER: Luis Severino (15-6) Yankees: Luis Severino (98/64) SAVE: Robert Gsellman (7) Mets: Jacob deGrom (114/79) HOME RUNS (2018 TOTAL / INNING / RUNNERS ON BASE / OUTS / COUNT / PITCHER / SCORE AFTER HR) YANKEES METS Miguel Andújar (#18 / 8th / 2 on / 2 out / 1-0 / Lugo / NYM 7 – NYY 5) Amed Rosario (#5 / 1st / 0 on / 0 out / 3-1 / Severino / NYM 1 – NYY 0) José Bautista (#9 / 4th / 1 on / 0 out / 3-2 / Severino / NYM 4 – NYY 2) Todd Frazier (#11 / 6th / 0 on / 0 out / 0-2 / Cole / NYM 5 – NYY 3) Brandon Nimmo (#15 / 7th / 0 on / 1 out / 1-1 / Cole / NYM 6 – NYY 3) Michael Conforto (#16 / 7th / 0 on / 1 out / 1-1 / Cole / NYM 7 – NYY 3) NEW YORK YANKEES NOTES • The Yankees fell to 3-2 on their season-long 11-game homestand…are 6-2 in their last 8G…are a season-high 10.0G behind first-place Boston (idle tonight), their largest division deficit since finishing the 2016 season 10.0G back. • Suffered their second series loss of the season (also 1-3 from 4/5-8 vs. -

Sports Golf » 5 Sidelines » 6 SATURDAY, JUNE 20, 2020 • the PRESS DEMOCRAT • SECTION C Weather » 6

Inside Baseball » 2 Sports Golf » 5 Sidelines » 6 SATURDAY, JUNE 20, 2020 • THE PRESS DEMOCRAT • SECTION C Weather » 6 CORONAVIRUS SRJC » FOOTBALL Players across A teammate gone leagues Rashaun Harris, a defensive infected back on the Santa Rosa Junior College Bear Cubs football team, was killed 49ers player, several in in a drive-by shooting baseball, hockey tested while visiting his family in Sacramento in May. His positive this week older sister believes it was a case of mistaken identity. In PRESS DEMOCRAT NEWS SERVICES these photos shared by his family and SRJC coach Len- ny Wagner, Harris is seen as PHILADELPHIA — The San he poses with a teammate, Francisco Giants shuttered as a young teen, in his SRJC their spring complex due to uniform and at the beach. fears over exposure to the coro- He was 23. navirus and at least two other teams did the same Friday af- ter players and staff tested pos- itive, raising the possibility the ongoing pandemic could scuttle all attempts at a Major League Baseball season. Elsewhere, an unidentified San Francisco 49ers player reportedly tested positive for COVID-19 after an informal workout with teammates in Tennessee. The NFL Network reported PHOTOS Friday that one player who took COURTESY OF DAJONNAE HARRIS part in the workouts this week AND LENNY WAGNER in Nashville has tested positive. All the players who were there will now get tested to see if there is any spread. The Giants’ facility was shut after one person who had been to the site and one family member exhibited symptoms Thursday. -

Weller Credits 2019

Production Design and Art Direction United Scenic Artists, Local 829 IATSE 505 Court Street 7P, Brooklyn NY 11231 NYC 212 9797761 Los Angeles 310 3981982 [email protected] IMDB: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0919860/ LINKEDIN: www.linkedin.com/in/wellerdesign www.wellerdesign.com Production Design and Art Direction for film, television and theater. Extensive experience in single and multi camera art direction for features and network/cable television. Skillful, meticulous budgeting combined with quick and accurate drafting. Expertise in assembling and managing crews. Multiple Emmy Awards. Series NEW AMSTERDAM – Network Series - NBC UNIVERSAL 2019 Art Director ARMISTEAD MAUPIN’S TALES OF THE CITY – Mini Series- NETFLIX 2019 Assistant Art Director FIRST WIVE’S CLUB – PARAMOUNT NETWORK 2018 Art Director JESSICA JONES SEASON 3 - MARVEL PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX 2018 Assistant Art Director JULIE’S GREENROOM – JIM HENSON PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX –2016 Art Director QUANTICO – ABC - 2016 Assistant Art Director Feature Film LOST GIRLS – NETFLIX 2018 Art Director THE COMMUTER – LIONSGATE -2017 Assistant Art Director BRAWL IN CEL BLOCK 99 - RLJE FILMS - 2017 Art Department THE PERFECT GENTLEMAN – SHORT - 2010 Production Design BAD LIEUTENANT –ARIES FILMS -1992 Set Designer THE RAPTURE - FINE LINE FEATURES - 1991 Set Designer THE BLOODHOUNDS OF BROADWAY – COLUMBIA PICTURES - 1989 Assistant Art Director Live Events THE NEW LEVANT - KENNEDY CENTER 2018 GLAMOUR WOMEN OF THE YEAR- CONDE NAST Carnegie Hall 2016, 2017 ALICIA KEYS FOR VEUVE CLIQUOT – Liberty -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

At NEW YORK METS (27-33) Standing in AL East

OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION YANKEE STADIUM • ONE EAST 161ST STREET • BRONX, NY 10451 PHONE: (718) 579-4460 • E-MAIL: [email protected] • SOCIAL MEDIA: @YankeesPR & @LosYankeesPR WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2018 (2017) NEW YORK YANKEES (41-18) at NEW YORK METS (27-33) Standing in AL East: ............1st, +0.5 RHP Domingo Germán (0-4, 5.44) vs. LHP Steven Matz (2-4, 3.42) Current Streak: ...................Won 3 Current Road Trip: ................... 6-1 Saturday, June 9, 2018 • Citi Field • 7:15 p.m. ET Recent Homestand: ................. 4-2 Home Record: ..............22-9 (51-30) Game #61 • Road Game #30 • TV: FOX • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM (English), WADO 1280AM (Spanish) Road Record: ...............19-9 (40-41) Day Record: ................16-4 (34-27) Night Record: .............24-14 (57-44) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play the second game of HOPE WEEK 2018 (June 11-15): This Pre-All-Star ................41-18 (45-41) their three-game Subway Series at the Mets (1-0 so far)…are 6-1 year marks the 10th annual HOPE Week Post-All-Star ..................0-0 (46-30) on their now-nine-game, four-city road trip, which began with a (Helping Others Persevere & Excel), vs. AL East: .................15-9 (44-32) rain-shortened two-game series in Baltimore (postponements an initiative rooted in the belief that vs. AL Central: ..............11-2 (18-15) on 5/31 and 6/3), a split doubleheader in Detroit on Monday acts of good will provide hope and vs. -

Arthouse Film Festival, When Asked How He Made It Look Children Training in the Martial Arts.” Beginning This Month at AMC Loews Mountainside

Page 16 Thursday, September 2, 2010 The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES A WATCHUNG COMMUNICATIONS, INC. PUBLICATION Westfield Resident Tsirigotis ‘Goes to the Mat’ for Martial Arts By MARYLOU MORANO A student of martial arts since he was area. Westfield Boy LaVelle Appears Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times 11, Mr. Tsirigotis holds a black belt in One would expect that with this abun- WESTFIELD – “Back to school” Taekwondo and is the originator of his dance of experience, the author would not only means getting back to the own system of martial arts; it is based take a stance that martial arts are for books; it means heading back to after- on pankration, a combat sport that – every child. Instead, his unbiased look On the YES Network, WFAN Radio school activities as well. blending boxing and wrestling with at martial arts and the martial arts in- strategy – was introduced into the Greek dustry allows each parent to make the By CHRISTIE STORMS meeting the New York Yankees at show, simulcast on TV via the YES Olympic Games in 648 BC and which best decision for his or her child. He Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times their new stadium come true. And (Yankees Entertainment & Sports) featured the philosopher Plato among provides the benefits of martial arts WESTFIELD — In May, the this past week, the same charitable Network and on WFAN 66 AM Ra- its participants. training, but he also provides a list of Make-A-Wish Foundation made 9- organization invited Connor to ap- dio. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1. -

Denver Broncos Weekly Release Packet

Denver broncos 2015 weekly press release Denver Broncos Football Media Relations Staff: Patrick Smyth, Vice President of Public Relations • (303-264-5536) • [email protected] Erich Schubert, Senior Manager of Media Relations • (303-264-5503) • [email protected] Seth Medvin, Media Relations Coordinator • (303-264-5608) • [email protected] 2 World Championships • 7 Super Bowls • 9 AFC Title Games • 14 AFC West Titles • 21 Playoff Berths • 27 Winning Seasons week PAT BOWLEN TO BE INDUCTED INTO #8 DENVER BRONCOS RING OF FAME Denver Broncos (6-0) vs. Green Bay Packers (6-0) Sunday, Nov. 1, 2015 • 6:30 p.m. MST Sports Authority Field at Mile High (76,125) • Denver Broncos Owner Pat Bowlen will be officially enshrined into the Denver Broncos Ring of Fame during a halftime ceremony on Sunday when the BROADCAST INFORMATION Broncos host the Green Bay Packers at Sports Authority Field at Mile High. Mr. Bowlen’s indelible contributions to the Broncos, the community and TELEVISION: NBC (KUSA-TV) Al Michaels (play-by-play) the NFL have established him as one of the greatest contributors in profes- Cris Collinsworth (color analyst) sional football history. Michele Tafoya (sideline) * - During Pat Bowlen’s tenure (1984-pres.), the Broncos have produced NATIONAL RADIO: WestwoodOne Sports Kevin Kugler (play-by-play) the third-best winning percentage (.614) of any team in American profes- sional sports. See Page 9 James Lofton (color analyst) * - Pat Bowlen has experienced more Super Bowl appearances (6) than LOCAL RADIO: KOA (850 AM) Dave Logan (play-by-play) losing seasons (5) in his 31 years with the team. -

Former Hostage to Speak at ND by SEAN S

ACCENT: Holy Cross Associates in Chile Balmy Mostly sunny, high in the mid VIEWPOINT: Don’t overlook poverty 70s. JEJ T h e O b s e r v e r ___________________ VOL . XXI, NO. 43 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1987 the independent newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's Former hostage to speak at ND By SEAN S. HICKEY Damascus, Syria, in Nov. 1984. Staff Reporter “They met with Syrian offi cials, Palestinian ■‘groups and A former Beirut hostage will almost anyone they could find, be speaking tonight at Galvin including representatives of Life Science at 8 in room 283. Syrian prime-minister Assad,” A Beirut bureau chief for the said Gaffney. He added it is un Cable News Network and pres clear whether Levin escaped ently a Woodrow Wilson Fellow because of his own ingenuity or at Princeton University, Jerry his wife’s efforts. Levin was abducted by the Is “The mystery is whether he lamic Jihad on March 7, 1984 escaped or was released in while walking to work in directly,” said Gaffney. “Most Beirut. The militant Shi’ite observers feel that it was spe group held him prisoner for 343 cial that he got away as op days until February 1985. posed to a disguised release. “Notre Dame had a secret Anyway it is clear that Lucille connection in Levin’s escape,” Levin met her husband’s cap said Father Patrick Gaffney, tors.” an assistant professor and a Islamic Jihad, a radical Middle East specialist. Shi’ite Muslim group issued a That connection was statement the week after they Landrum Bolling, director of released Levin saying they the Notre Dame Institute of decided to do so because they Ecumenical Studies in Israel, determined he was not a sub who was contacted by Levin’s versive.