The Making of Hong Kong.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

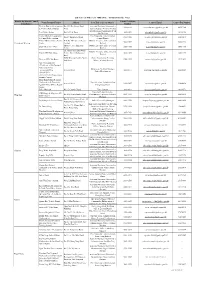

Police Report Rooms Receiving 992 Emergency SMS Service Applications S/N Region Report Room Address of Report Room 1

Police Report Rooms receiving 992 Emergency SMS Service Applications S/N Region Report Room Address of Report Room 1. Central District No.2 Chung Kong Road, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 2. Peak Sub-Division No.92 Peak Road, Hong Kong 3. Western Division No.280 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 4. Aberdeen Division No.4 Wong Chuk Hang Road , Hong Kong Hong Kong 5. Stanley Sub-Division No.77 Stanley Village Road, Stanley, Hong Kong Island 6. Wan Chai Division No. 1 Arsenal Street, Wanchai, Hong Kong 7. Happy Valley Division No.60 Sing Woo Road, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 8. North Point Division No.343 Java Road, Hong Kong 9. Chai Wan Division No.6 Lok Man Road, Chai Wan , Hong Kong 10. Tsim Sha Tsui Division No.213 Nathan Road, Kowloon 11. Yau Ma Tei Division No.3 Yau Cheung Road, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon 12. Sham Shui Po Division No. 37A Yen chow Street, Kowloon Kowloon 13. Cheung Sha Wan Division No. 880 Lai Chi Kok Road, Kowloon West 14. Mong Kok District No. 142 Prince Edward Road West, Kowloon 15. Kowloon City Division No. 202 Argyle Street, Kowloon 16. Hung Hom Division No.99 Princess Margaret Road, Kowloon 17. Wong Tai Sin District No.2 Shatin Pass Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon 18. Sai Kung Division No.1 Po Tung Road, Sai Kung, Kowloon 19. Kowloon Kwun Tong District No.9 Lei Yue Mun Road, Kwun Tong, Kowloon 20. East Tseung Kwan O District No.110 Po Lam Road North, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon 21. -

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wan Chai Block C, Fontana Garden 5868 Yau Tsim Mong Cam Key Mansion, 495 Shanghai Street 5869 Kowloon City Crystal Mansion 5870 Central & Western Best Western Plus Hotel Hong Kong 5871 Central & Western Tower 1, Kong Chian Tower 5872 Wan Chai 11 Broom Road 5873 Kwai Tsing Wah Shun Court 5874 Kowloon City Sunderland Estate 5875 Islands Headland Hotel 5877 Eastern Block A, Yen Lok Building 5879 Sha Tin Hin Kwai House, Hin Keng Estate 5880 Tai Po Po Sam Pai Village 5881 Sha Tin Mei Chi House, Mei Tin Estate 5882 Tsuen Wan Block 2, Waterside Plaza 5882 Sha Tin Jubilee Court, Jubilee Garden 5883 Kwun Tong Lee Ming House, Shun Lee Estate 5884 Southern Tower 9, Bel-Air On The Peak 5885 Central & Western Block 3, Garden Terrace 5886 Sai Kung Tower 5, The Mediterranean 5887 Sai Kung Tower 5, The Mediterranean 5888 Kowloon City Block 1, Kiu Wang Mansion 5889 Islands Heung Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5890 Sha Tin Cypress House, Kwong Yuen Estate 5891 Kwai Tsing Block 6, Mayfair Gardens 5892 Eastern Tower 1, Harbour Glory 5893 Sai Kung Kap Pin Long 5894 Wan Chai Hawthorn Garden 5895 Tai Po Villa Castell 5896 Kwun Tong Ping Shun House, Ping Tin Estate 5897 Sai Kung Tak Fu House, Hau Tak Estate 5898 Kwai Tsing Ying Kwai House, Kwai Chung Estate 5899 1 Related Confirmed / -

Facilities in Henry G. Leong Yaumatei Community Centre and Exemptions from Payment of Charges for Use of Facilities

Annex A(I) Facilities in Henry G. Leong Yaumatei Community Centre and Exemptions from Payment of Charges for Use of Facilities (1) Facilities in Henry G. Leong Yaumatei Community Centre Facility Features Multi-purpose Hall The seating capacity is up to 522, including 360 movable seats in the 1/F Hall and 162 fixed seats in the 3/F Balcony. There are 4 additional wheelchair spaces in the Balcony. The 1/F Hall can accommodate up to a maximum of 400 persons, while the 3/F Balcony can accommodate up to 176 persons, including no more than 10 standing staff of the hirer. The minimum number of participants for use of the Multi-purpose Hall is 50. Chairs, tables, exhibition boards, A4/A1 display stands, DVD player, cassette player, lighting system, sound system, piano, projector and stage banner gallows are available (Remark: Technical information of the Hall is detailed at Annex A(IV)). Hirers should deploy their own qualified technicians to operate the lighting and sound consoles as well as arrange seats and conduct venue clearance after use by themselves. Hirers are liable to compensate any damage caused to the facilities. Conference Room* The room, the floor area of which is about 95m2, has a seating capacity of about 120 persons. The conference table has a seating capacity of about 22 persons. Folding tables (6 pieces), chairs (120 pieces), basic PA system (2 wireless microphones), whiteboard, multi-media projector and screen are available. Classroom *# The room, the floor area of which is about 57m2, has a seating capacity of about 50 persons. -

Big Buy Reimbursement Program Property Status.2010-07-02.Xlsx Page 1 of 295

Big Buy Reimbursement Program Property Status.2010-07-02.xlsx Page 1 of 295 Multifamily Hub Name Property Name City State Official Big Buy Status BBRP Status Not Interested in Atlanta ADA FERRELL GARDEN APTS (THDA) TULLAHOMA TN Participating Ineligible: inactive in iREMS Evaluation Report Mailed Atlanta ADAIRVILLE ARMS APARTMENTS ADAIRVILLE KY to the Owner Ineligible: Evaluation Completed Evaluation Report Mailed Atlanta ALCO APTS SCOTTSVILLE KY to the Owner Ineligible: Evaluation Completed Evaluation Report Mailed Atlanta ALDERMAN GARDEN APARTMENTS FLATWOODS KY to the Owner Ineligible: Evaluation Completed Not Interested in Atlanta Alpha A Fowler Community DOUGLASVILLE GA Participating Ineligible: Exempt Evaluation Report Mailed Atlanta ALTA LOMA APTS NASHVILLE TN to the Owner Ineligible: inactive in iREMS Evaluation Report Mailed Atlanta ALTURAS DEL SENORIAL SAN JUAN PR to the Owner Ineligible: Evaluation Completed Not Interested in Atlanta AMBER VILLAGE EDDYVILLE KY Participating Ineligible: Exempt Atlanta ANDERSON PLACE LOUISVILLE KY Interested in Participating Ineligible: Exempt Evaluation Report Mailed Atlanta Anthony Arms L P MACON GA to the Owner Ineligible: Evaluation Completed Not Interested in Atlanta AQUEDUCT PLACE, INC. LEXINGTON KY Participating Ineligible: Exempt Not Interested in Atlanta Ashley House Apartments VALDOSTA GA Participating Ineligible: Exempt Not Interested in Ineligible: Not Interested in Atlanta Athens Gardens ATHENS GA Participating Participating Evaluation Report Mailed Atlanta Augusta Manor AUGUSTA GA -

Name of Buildings Awarded the Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings – Fresh Water (Plus) Certificate (As at 8 February 2018)

Name of Buildings awarded the Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings – Fresh Water (Plus) Certificate (as at 8 February 2018) Name of Building Type of Building District @Convoy Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Eastern 1 & 3 Ede Road Private/HOS Residential Kowloon City 1 Duddell Street Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Central & Western 100 QRC Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Central & Western 102 Austin Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong 1063 King's Road Private/HOS Residential Eastern 11 MacDonnell Road Private/HOS Residential Central & Western 111 Lee Nam Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Southern 12 Shouson Hill Road Private/HOS Residential Central & Western 127 Repulse Bay Road Private/HOS Residential Southern 12W Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Tai Po 15 Homantin Hill Private/HOS Residential Yau Tsim Mong 15W Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Tai Po 168 Queen's Road Central Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Central & Western 16W Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Tai Po 17-19 Ashley Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong 18 Farm Road (Shopping Arcade) Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Kowloon City 18 Upper East Private/HOS Residential Eastern 1881 Heritage Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong 211 Johnston Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Wan Chai 225 Nathan Road Commercial/Industrial/Public Utilities Yau Tsim Mong Name of Buildings awarded the Quality Water Supply Scheme for Buildings – Fresh Water (Plus) -

District : Tsuen

District : Tsuen Wan Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Projected Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16 599) K01 Tak Wah 15 475 -6.77 N Sai Lau Kok Road 1. CHUNG ON BUILDING 2. FOU WAH CENTRE NE Sai Lau Kok Road 3. HO FAI GARDEN E Kwan Mun Hau Street, Sai Lau Kok Road 4. KOLOUR - TSUEN WAN 1 5. TAK YAN BUILDING (PART) : Shing Mun Road Stage 2 SE Kwan Mun Hau Street Stage 4 S Sha Tsui Road Stage 6 Stage 7 SW Sha Tsui Road Stage 8 W Sha Tsui Road, Tai Ho Road 6. TSUEN CHEONG CENTRE 7. TSUEN WAN TOWN SQUARE NW Tai Ho Road, Tai Ho Road North 8. WAH SHING BUILDING K 1 District : Tsuen Wan Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Projected Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16 599) K02 Yeung Uk Road 17 799 +7.23 N Kwan Mun Hau Street, Sha Tsui Road 1. BO SHEK MANSION 2. EAST ASIA GARDENS NE Castle Peak Road - Tsuen Wan 3. HARMONY GARDEN Texaco Interchange, Texaco Road 4. NEW HAVEN 5. SHEUNG CHUI COURT Texaco Road Flyover 6. TSUEN WAN GARDEN E Texaco Road 7. WEALTHY GARDEN SE Texaco Road S Yeung Uk Road SW Yeung Uk Road W Chung On Street, Ho Pui Street Yeung Uk Road NW Chuen Lung Street, Sha Tsui Road K 2 District : Tsuen Wan Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Projected Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16 599) K03 Tsuen Wan South 19 623 +18.22 N Chuen Lung Street, Ho Pui Street 1. -

Driving Services Section

DRIVING SERVICES SECTION Taxi Written Test - Part B (Location Question Booklet) Note: This pamphlet is for reference only and has no legal authority. The Driving Services Section of Transport Department may amend any part of its contents at any time as required without giving any notice. Location (Que stion) Place (Answer) Location (Question) Place (Answer) 1. Aberdeen Centre Nam Ning Street 19. Dah Sing Financial Wan Chai Centre 2. Allied Kajima Building Wan Chai 20. Duke of Windsor Social Wan Chai Service Building 3. Argyle Centre Nathan Road 21. East Ocean Centre Tsim Sha Tsui 4. Houston Centre Mody Road 22. Eastern Harbour Centre Quarry Bay 5. Cable TV Tower Tsuen Wan 23. Energy Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 6. Caroline Centre Ca useway Bay 24. Entertainment Building Central 7. C.C. Wu Building Wan Chai 25. Eton Tower Causeway Bay 8. Central Building Pedder Street 26. Fo Tan Railway House Lok King Street 9. Cheung Kong Center Central 27. Fortress Tower King's Road 10. China Hong Kong City Tsim Sha Tsui 28. Ginza Square Yau Ma Tei 11. China Overseas Wan Chai 29. Grand Millennium Plaza Sheung Wan Building 12. Chinachem Exchange Quarry Bay 30. Hilton Plaza Sha Tin Square 13. Chow Tai Fook Centre Mong Kok 31. HKPC Buil ding Kowloon Tong 14. Prince ’s Building Chater Road 32. i Square Tsim Sha Tsui 15. Clothing Industry Lai King Hill Road 33. Kowloonbay Trademart Drive Training Authority Lai International Trade & King Training Centre Exhibition Centre 16. CNT Tower Wan Chai 34. Hong Kong Plaza Sai Wan 17. Concordia Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 35. -

Participating Buildings in Sha Tin District 沙田區的參與屋苑

Sha Tin (沙田) Estates (屋苑) Estate/Building 屋苑/大廈 10 Lok Fung Path 樂楓徑10號政府宿舍 6 Lok Fung Path 樂楓徑6號政府宿舍 Baycrest 觀瀾雅軒 Bayshore Towers 海栢花園 Belair Gardens 富豪花園 Castello 帝堡城 Chun Shek Estate 秦石邨 Chung On Estate 頌安邨 Chung Yeung Estate 駿洋邨 City One 置富第一城 City One Shatin 沙田第一城 Conifer Lodge 匡怡居 Double Cove (Phase 1) 迎海 Festival City 名城 Ficus Garden 榕翠園 Fok On Garden 福安花園 Fu Fai Garden 富輝花園 Fung Shing Court 豐盛苑 Fung Wo Estate 豐和邨 Garden Rivera 河畔花園 Garden Vista 翠湖花園 Glamour Garden 金輝花園 Golden Lion Garden Phase I 金獅花園第I期 Golden Lion Garden Phase II 金獅花園第II期 Grandway Garden 富嘉花園 Granville Garden 恆峰花園 Green Leaves Garden 翠麗花園 Greenary Villas Phase 2 寶翠小築二期 Estate/Building 屋苑/大廈 Greenview Garden 愉景花園 Greenwood Garden 翠華花園 Greenwood Terrace 華翠園 Heng On Estate 恆安邨 Hill Lodge 曉廬 Hill Paramount 名家匯 Hilton Plaza 希爾頓中心 Hin Keng Estate 顯徑邨 Hin Yiu Estate 顯耀邨 Hong Kong Baptist University Staff Quarters 香港浸會大學職員宿舍 Hong Lam Court 康林苑 Jat Min Chuen 乙明邨 Jubilee Garden 銀禧花園 Julimount Garden 瑞峰花園 Ka Keng Court 嘉徑苑 Ka Tin Court 嘉田苑 Kam Fung Court 錦豐苑 Kam Hay Court 錦禧苑 Kam Lung Court 錦龍苑 Kam On Court 錦鞍苑 Kam On Garden 金鞍花園 Kam Tai Court 錦泰苑 Kam Ying Court 錦英苑 Kwong Lam Court 廣林苑 Kwong Yuen Disciplined Services Quarters 廣源紀律部隊宿舍 Kwong Yuen Estate 廣源邨 La Costa 嘉華星濤灣 La Cresta 尚珩 Lake Silver 銀湖‧天峰 Lakeview Garden 湖景花園 Lee On Estate 利安邨 Estate/Building 屋苑/大廈 Lee Woo Sing College 香港中文大學和聲書院 Lek Yuen Estate 瀝源邨 Lung Hang Estate 隆亨邨 Ma On Shan Centre 馬鞍山中心 Marbella 迎濤灣 May Shing Court 美城苑 Mei Chung Court 美松苑 Mei Lam Estate 美林邨 Mei Pak Court 美柏苑 Mei Tin Estate 美田邨 Monte -

List of Radio Dealer (Unrestricted) Licensees (As at 16/08/2021)

List of Radio Dealer (Unrestricted) Licensees 無線電商(放寬限制)持牌商名單 ( As at 16/09/2021) (截至 16/09/2021) Licensee Address Telephone Licence No. (Ex-Licence No.) 持牌商 地址 電話 牌照號碼 (原有牌照號碼) RM. G87, G/F, SINCERE PODIUM, , MONG KOK 1 + 1 九龍旺角先達廣場地下G87號舖 55926692 RU00231996-RU 188 TELECOM GROUP LIMITED RU00119316-RU 188 電訊集團有限公司 G/F, 188 APLIU ST, SHAM SHUI PO 35860072 (11931) 188 TELECOM O/B 188 TELECOM GROUP LIMITED 188電訊 O/B 188電訊集團有限公司 G/F, 209 APLIU ST, SHAM SHUI PO 23207788 RU00180442-RU 2626 LIMITED RM. /FLAT 1, 5/F, BLK A, HOI LUEN INDUSTRIAL CENTRE, 55 HOI YUEN ROAD, KWUN TONG 97804506 RU00158065-RU 28 FOOD (HK) LIMITED G/F, 204 FA YUEN STREET, MONG KOK 易發食品(香港)有限公司 九龍旺角花園街204號地下 26939008 RU00222985-RU 2DEEP INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 泰森國際貿易有限公司 RM. /FLAT A, 12/F, ZJ 300, 300 LOCKHART ROAD, WAN CHAI 51731646 RU00230817-RU 360 KIDS GUARD CO. LIMITED 2/F, YAU TAK BUILDING, 167 LOCKHART ROAD, WAN CHAI 21563920 RU00216069-RU 365 DAYS FREIGHT SERVICES (HK) LIMITED 5/F, BLK F, COMFORT BUILDING, 86-88A NATHAN ROAD, TSIM SHA TSUI +852 62213657 RU00220056-RU 3M HONG KONG LTD RU00132097-RU 三M香港有限公司 38/F, MANHATTAN PLACE, 23 WANG TAI ROAD, KOWLOON BAY 28066111 (13209) 4&6 TELECOM LIMITED RM. /FLAT 01, 11/F, HANG SENG CASTLE PEAK RD BLDG, 339 CASTLE PEAK RD, CHEUNG SHA WAN +852 66493320 RU00202666-RU 409 SHOP RU00128365-RU 409專門店 RM. /FLAT D-E, 11/F, FLOURISH FOOD MFY CTR, 18 TAI LEE STREET, YUEN LONG 35860967 (12836) 4PX EXPRESS CO., LIMITED RU00129432-RU 遞四方速遞有限公司 G/F, 167-169 HOI BUN ROAD, KWUN TONG 29772988 (12943) 5 CELL RM. -

APRIL Outpatient Direct Billing General Network

APRIL Outpatient Direct Billing General Network INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF USE APRIL’s Outpatient Direct Billing Network is designed to provide our members with a service that makes claiming for outpatient services quick and convenient. When members with outpatient benefits and holding a valid APRIL Member Card (or eCard) use medical facilities within our network, APRIL will settle eligible medical expenses incurred directly with the medical provider. Only members without coinsurance can use direct billing services. Please note that Moratorium policies are not eligible to this service. Use of this list is governed by your Policy’s Terms and Conditions and is also subject to the guidelines, exclusions and remarks listed below. Download our Easy Claim app on your smartphone to search and locate healthcare providers within our Asia network: With the app, you can: ✓ Search a healthcare practitioner by name, location, or specialty. ✓ Check whether you are eligible for direct billing in the displayed facilities. To verify your eligibility for direct billing, log in to the app and click on the “E-card” button: • If the code “DB” is displayed on your card, you are eligible for direct billing within our whole Asia General Network. • If the code “PNW” is displayed, you can enjoy direct billing within our Asia Panel Network (please refer to this listing). If you encounter any issues why using direct billing or have any questions about the service, please contact your local APRIL office. You may find your contacts below your eCard on your Easy Claim app. Inpatient Direct Billing For inpatient treatment, APRIL can arrange direct billing if proper notification and documentation are provided and subject to the hospital’s agreement. -

Recommended District Council Constituency Areas

District : Sha Tin Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,282) R01 Sha Tin Town Centre 21,347 +23.52 N Tung Lo Wan Hill Road, To Fung Shan Road 1. HILTON PLAZA 2. LUCKY PLAZA Tai Po Road - Sha Tin 3. MAN LAI COURT NE Sha Tin Rural Committee Road 4. NEW TOWN PLAZA 5. PEAK ONE E Sha Tin Rural Committee Road 6. PRISTINE VILLA Sand Martin Bridge 7. SCENERY COURT Shing Mun River Channel 8. SHA TIN CENTRE 9. SHATIN PLAZA SE Sand Martin Bridge 10. TUNG LO WAN Shing Mun River Channel, Lek Yuen Bridge 11. WAI WAH CENTRE Lion Rock Tunnel Road S Shing Mun River Channel SW Shing Mun River Channel Shing Chuen Road, Tai Po Road - Tai Wai W Tai Po Road – Tai Wai Shing Mun Tunnel Road NW Shing Mun Tunnel Road Tung Lo Wan Hill Road R1 District : Sha Tin Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,282) R02 Lek Yuen 13,050 -24.49 N Fo Tan Road 1. HA WO CHE 2. LEK YUEN ESTATE NE Fo Tan Road, MTR (East Rail Line) 3. PAI TAU Lok King Street, Nullah, Sha Tin Road 4. SHEUNG WO CHE 5. WO CHE ESTATE (PART) : E Tai Po Road - Sha Tin, Fung Shun Street King Wo House Wo Che Street, Shing Mun River Channel 6. YAU OI TSUEN SE Shing Mun River Channel S Shing Mun River Channel Sand Martin Bridge Sha Tin Rural Committee Road Tai Po Road - Sha Tin, To Fung Shan Road SW To Fung Shan Road, Tung Lo Wan Hill Road W To Fung Shan Road NW To Fung Shan Road R2 District : Sha Tin Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,282) R03 Wo Che Estate 18,586 +7.55 N Tai Po Road - Sha Tin, Fo Tan Road 1.