“I Am Also a We”: the Interconnected, Intersectional Superheroes of Netflix's Sense8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audience Affect, Interactivity, and Genre in the Age of Streaming TV

. Volume 16, Issue 2 November 2019 Navigating the Nebula: Audience affect, interactivity, and genre in the age of streaming TV James M. Elrod, University of Michigan, USA Abstract: Streaming technologies continue to shift audience viewing practices. However, aside from addressing how these developments allow for more complex serialized streaming television, not much work has approached concerns of specific genres that fall under the field of digital streaming. How do emergent and encouraged modes of viewing across various SVOD platforms re-shape how audiences affectively experience and interact with genre and generic texts? What happens to collective audience discourses as the majority of viewers’ situated consumption of new serial content becomes increasingly accelerated, adaptable, and individualized? Given the range and diversity of genres and fandoms, which often intersect and overlap despite their current fragmentation across geographies, platforms, and lines of access, why might it be pertinent to reconfigure genre itself as a site or node of affective experience and interactive, collective production? Finally, as studies of streaming television advance within the industry and academia, how might we ponder on a genre-by- genre basis, fandoms’ potential need for time and space to collectively process and interact affectively with generic serial texts – in other words, to consider genres and generic texts themselves as key mediative sites between the contexts of production and those of fans’ interactivity and communal, affective pleasure? This article draws together threads of commentary from the industry, scholars, and culture writers about SVOD platforms, emergent viewing practices, speculative genres, and fandoms to argue for the centrality of genre in interventions into audience studies. -

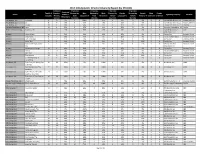

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE TELECOM ITALIA TO BRING NETFLIX TO TIMVISION TIM to offer easy access to the broad variety of Netflix TV shows & movies Partnership will contribute to the expansion of ultra-broadband in Italy Rome, 29 July 2015 Telecom Italia group and Netflix today announced an agreement to deliver easy access to Netflix to TIM's customers directly on the TIMvision set-top box. With this agreement TIM further confirms its commitment to disseminate innovative services – particularly in the entertainment space – also to contribute to the expansion of ultra-broadband in Italy, being the leading technological enabler thanks to its superfast fixed and mobile networks. TIM customers will have easy, on demand access to Netflix, the world’s leading Internet TV network. Netflix offers a wide selection of TV shows and movies, award-winning Netflix originals, and a special section just for kids. Netflix programming will be available in HD quality, directly on the TV via the TIMvision set-top box, on TIM’s fixed ADSL and UBB networks, the most broadly available networks in Italy. TIM and Netflix will work together to provide TIM’s customers an easy way to access the Netflix app and enable best streaming quality experience. At launch, the Netflix offering will include such exclusive Netflix Original series as Marvel’s Daredevil, Sense8, Bloodline, Grace and Frankie, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and Marco Polo and critically acclaimed documentaries Virunga, Mission Blue and docuseries Chef’s Table as well as various stand-up comedy specials. Additionally, younger viewers will find a wide selection of programming for kids. -

Bollywood Produces More Movies in a Year Than Hollywood

a-z CONTENTS a ANALYZE, ANALYZE, ANALYZE by Klara Gavran P6 b BLOCKBUSTER PHENOMENON by Klara Malnar P12 c CINEMAS, ARE THEY DYING? by Klara Malnar P17 d DID YOU KNOW? by Irma Jakić P22 e ENTERTAINMENT MARKETING IN 2019 by Klara Malnar P27 f FAMOUS CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENTS by Irma Jakić P30 g GO BIG OR GO HOME by Irma Jakić P31 h HOLLYWOOD VS BOLLYWOOD by Klara Malnar P35 i I WANT TO THANK THE ACADEMY…AND MY CAMPAIGN STRATEGIST by Klara Malnar P38 j JOYS OF DIGITALIZATION by Klara Gavran P43 k KEEPING UP WITH THE STREAMING SERVICES by Klara Gavran P47 l LEANING INTO SOCIAL LISTENING by Klara Gavran P51 m MUSICIANS TO ACTORS AND VICE VERSA by Irma Jakić P60 n NOT YOUR AVERAGE MARKETING CAMPAIGN by Klara Gavran P62 o OFF-CAMERA: ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY BY THE DOLLAR by Irma Jakić P71 p PR NIGHTMARE, BUT LONG OVERDUE by Iva Anušić P75 q QUICK FIX by Iva Anušić P79 r RAZZIES by Irma Jakić P88 s SOCIAL MEDIA’S IMPACT ON THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY by Klara Malnar P90 t THE COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS: HOW CAN STREAMING SERVICES BENEFIT by Klara Gavran P96 u USER-GENERATED CONTENT by Klara Malnar P99 v VIEWER’S CHOICE by Klara Gavran P103 w WHAT ABOUT FILM FESTIVALS? by Klara Malnar P105 x X FACTOR by Irma Jakić P111 y YHBT (YOU HAVE BEEN TROLLED) CULTURE by Iva Anušić P113 z ZOMBIES by Irma Jakić P116 a ANALYZE, ANALYZE, ANALYZE “Pay attention to what the people and the start a few months, half a year, or even a whole press are talking about. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Star Channels, March 18-24

MARCH 18 - 24, 2018 staradvertiser.com BY THE BOOK A killer takes a bestselling book about crime theory a little too literally in Instinct, a police procedural with a modern touch. In order to solve his murders, Det. Lizzie Needham (Bojana Novakovic) will need the author’s help. Watch as Dr. Dylan Reinhart (Alan Cumming), a former CIA operative-turned-professor and author, joins Needham in order to create a profi le and help catch the killer. Premiering Sunday, March 18, on CBS. WEEKLY NEWS UPDATE LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss upcoming legislation and issues of importance to the community. TOMORROW, 8:30AM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 olelo.org ON THE COVER | INSTINCT The write wit Remixing police procedurals Without any motives or additional leads, following and firmly established the demand Needham reaches out to Reinhart for his help, for the police procedural drama. with ‘Instinct’ knowing that his unique perspective as author “Instinct” pulls from this transitory past, as — and former CIA operative — is her best hope the story began in the pages of a novel. The By K.A. Taylor at stopping this mysterious murderer. series is an adaptation of James Patterson’s TV Media To better prepare himself for the chase, novel “Murder Games,” with much of the Reinhart calls on some old friends for assis- series’ content staying true to Patterson’s olice procedural dramas are a staple of tance from his previous life, including Julian own words. Fans of literary, small-screen and North American television. Just mention- Cousins (Naveen Andrews, “Sense8”). -

Netflix's Sense8 and Accompanying Twitter Communication Transnationale Ident

Transnational Identity in Online Discourse – Netflix’s Sense8 and accompanying Twitter communication Transnationale Identität im Online Diskurs – Netflix’s Sense8 und Anschlusskommunikation auf Twitter by Anna Carolin Antonia Rohmann A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo and the Universitaet Mannheim in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Intercultural German Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada / Mannheim, Germany, 2020 © Anna Carolin Antonia Rohmann 2020 Author’s declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, in- cluding any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich versichere, dass ich die Arbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angege- benen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder sinngemäß aus Veröffentli- chungen in schriftlicher oder elektronischer Form entnommen sind, habe ich als solche unter Angabe der Quelle kenntlich gemacht. Mir ist bekannt, dass im Falle einer falschen Versiche- rung die Arbeit mit „nicht ausreichend“ bewertet wird. Ich bin ferner damit einverstanden, dass meine Arbeit zum Zwecke eines Plagiatsabgleichs in elektronischer Form versendet und gespeichert werden kann. Mannheim, 10.08.2020 ii Abstract Digital media has become ubiquitous and immensely shapes communitarisation, and thus identity construction. As media does not rely on physical border crossing to bring us in con- tact with different subject positions, traditional forms of mobility are not necessary to include people in transnational discourse and narratives of transnational identification. However, scholarly attention has been focused on discourses of transnational identities tied to tradition- al transgressions of national space. -

Call Me by Your Name Berlin Syndrome Mr. Stein Goes

2017 NEW IN SUNDANCE IN PARIS RENDEZ-VOUS UPCOMING CONTACTS IN PARIS THE APPARITION CALL ME MR. STEIN GOES THE MIDWIFE GRAND HOTEL by Xavier Giannoli BY YOUR NAME ONLINE by Martin Provost EMILIE GEORGES (January 12th – 15th) In Pre Production by Luca Guadagnino by Stephane Robelin Completed [email protected] / +33 6 62 08 83 43 SCRIPT AVAILABLE Premieres World Market Premiere GOOD TIME NICHOLAS KAISER (January 12th – 15th) PARIS PRESTIGE BERLIN SYNDROME by Ben & Joshua Safdie [email protected] / +33 6 43 44 48 99 by Hamé & Ekoué by Cate Shortland In Post Production MATHIEU DELAUNAY (January 12th – 15th) Screening in Paris World Competition [email protected] / + 33 6 87 88 45 26 WORLD MARKET PREMIERE THELMA by Joachim Trier In Post Production design: www.clade.fr / Graphic non-contractual Credits MY HAPPY FAMILY OFFICE IN PARIS by Nana & Simon SWEET COUNTRY MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL Sundance - World Competition by Warwick Thornton 9 Cité Paradis – 75010 Paris – France WORLD MARKET PREMIERE In Post Production Tel: +33 1 53 34 90 20 Fax: +33 1 42 47 11 24 DIAS [email protected] by Jonathan English [email protected] In Production www.memento-films.com Follow us on Facebook NEW IN PRE PRODUCTION THE APPARITION XAVIER GIANNOLI By the director of Marguerite, The Singer, In the Beginning With Vincent Lindon (Best Actor Cannes 2015 – The Measure of a Man, Rodin, Welcome) IN PRE PRODUCTION NEW SCRIPT AVAILABLE THE APPARITION A FILM BY XAVIER GIANNOLI By the director of Marguerite, (1,2 million admissions in France, 4 César Awards including Best Actress for Catherine Frot, Venice In Competition 2015), The Singer (Cannes In Competition 2006, César for Best Sound, Lumière Award for Best Actor to Gérard Depardieu) and In The Beginning (Cannes In Competition 2009) With Vincent Lindon (Best Actor Cannes 2015 – The Measure of a Man, Rodin, Welcome), Galatéa Bellugi (Keeper, Heal the Living) and Patrick D’Assumçao (Stranger by the Lake, Diary of a Chambermaid) Jacques is a journalist at a large regional newspaper in France. -

Signature Redacted

Perspectives on Film Distribution in the U.S.: Present and Future By Loubna Berrada Master in Management HEC Paris, 2016 SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2016 OFTECHNOLOGY 2016 Loubna Berrada. All rights reserved. JUN 08 201 The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic LIBRARIES copies of this thesis document in whole or in part ARCHIVES in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signature redE cted MIT Sloan School of Management May 6, 2016 Certified by: Signature redacted Juanjuan Zhang Epoch Foundation Professor of International Management Professor of Marketing MIT Sloan School of Management Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Signature redacted Rodrigo S. Verdi Associate Professor of Accounting Program Director, M.S. in Management Studies Program MIT Sloan School of Management 2 Perspectives on Film Distribution in the U.S.: Present and Future By Loubna Berrada Submitted to MIT Sloan School of Management on May 6, 2016 in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Management Studies. Abstract I believe film has the power to transform people's lives and minds and to enlighten today's generation like any other medium. This is why I wanted to write my thesis about film distribution as it will determine the future of the industry itself. The way films are distributed, accessed and consumed will be critical in shaping our future entertainment culture and the way we approach content. -

Sense8 Roundtable

Moya Bailey, micha cárdenas, Laura Horak, Lokeilani Kaimana, Cáel M. Keegan, Geneveive Newman, Roxanne Samer, and Raffi Sarkissian Sense8 Roundtable Abstract In “Sense8: A Roundtable,” eight scholars, myself included, think through key questions regarding one of today’s most impressive trans-produced mainstream media productions, Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s Netflix series Sense8, which has yet to receive substantive scholarly attention. We analyze how Sense8 both follows and breaks from the Wachowskis’ prior approach to narrative; offers a distinctly trans* engagement with the histories of cinematic and televisual genres; often relies on western colonial conceptions for its global imagination and marginalizes characters of color; and theorizes contemporary media spectatorship in its appeal to affect and eroticism. We do so believing Sense8 to be an important cultural interlocutor, not only with regard to the exploration of transgender representation but also questions of sexuality, race, and capital in the global present. However, we also share a conviction that the series’ potentiality still leaves substantial room for growth. We take a critical approach to our collective analysis, seeing in the series a glimmer of the kind of global utopian envisioning very much needed in our ceaselessly dystopian present. The first season of J. Michael Straczynski and was the prime decree of those reviewers who were Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s Sense8 was released looking to witness a similar “seamless marriage on Netflix on June 5, 2015. The series’ critical of style and substance.”2 Those reviewers who did reception was mixed. Many found Sense8—which appreciate Sense8 were those who saw the series as tells the story of eight individuals from across purposefully demanding the labor of an attentive the globe, who, having recently been “birthed” by audience. -

Overlooked Latinas the Best, Queer, Telenovela of Our Time!

For immediate release: Media Contact: [email protected] Brava presents Tina D'Elia’s Overlooked Latinas The best, queer, telenovela of our time! Directed by Mary Guzmán February 16 – March 3, 2019 Brava Theater Center Studio “Writer-performer Tina D'Elia's, solo comedy spins a queer and ethnically rich world… D'Elia, proves a sharp and engaging performer, her characters tending to be both endearing and amusingly full-bodied." - Robert Avila, San Francisco Bay Guardian From the unbridled imagination of Tina D'Elia comes her solo show Overlooked Latinas. Butch dyke Angel Torres thinks she's having the best day of her life. She and her best bud's TV pilot, "Overlooked Latinas," about beloved silver-screen Latinx folks of the past, has just been picked up. But like the best telenovelas of the era, Angel's life is about to become unhinged by a whole mess of melodrama. Enter the femme fatale creating chaos with Angel's wife and Angel's life. Bios: Tina D’Elia (Solo Performer/Writer/Actor) Tina D’Elia is an award-winning Bay Area solo performer, actor, screenwriter and casting director. Tina’s acting credits include The Pursuit of Happyness, Knife Fight, Guitar Man, Junkie, Trauma (NBC), Rellik (Pilot), the web series Sense8 (Netflix), and Dyke Central (Amazon). ). Her popular solo show, The Rita Hayworth of this Generation, directed by Mary Guzman, won Best of Fringe (2015) and Best of Sold Out Shows at the San Francisco Fringe Festival (2015). Tina and director Maria Breaux won the Frameline33 Film Festival Audience Award for co-writing the short -

P38 Layout 1

lifestyle MONDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2015 MOVIES BIFF ‘Queen ‘Birdman’ bests ‘Boyhood’ of the Desert’ on the road to the Oscars is no history lesson he long takes of Alejandro Inarritu’s In a special segment, Steven Spielberg also fter opening with an Arctic adventure, the “Birdman” won out over the long pro- announced that starting in 2016, the DGA Berlin International Film Festival heated up duction of Richard Linklater’s will award a prize for first-time feature film Friday with “Queen of the Desert,” a film about T A “Boyhood” at the Directors Guild Awards directors. “If we were to travel back in our British diplomat and spy Gertrude Bell starring Nicole Saturday. Both formally ambitious in very legacy, we might have honored Orson Kidman and James Franco. The film about Bell, who different ways, “Boyhood” and “Birdman” Welles for his masterpiece ‘Citizen Kane’ or played a key role in reshaping the Middle East during have been neck-in-neck throughout the Sidney Lumet for ‘12 Angry Men,’” said the early 20th century, comes at a time of renewed awards race. But after dominating the act- Spielberg. “Our hope is this new award will turmoil in the region. But director Werner Herzog ing and producing guild awards, Inarritu’s shine a light on up-and-coming voices.” insists it’s just a story, not a history lesson, and doesn’t tale about a washed-up actor looking for The solid predictive track record of the attempt to criticize those who carved up the Middle some authenticity on the New York stage DGAs might suggest that there was a cut- East by drawing lines in the sand 100 years ago.