An Investigation Into the Benefits and Processes of Adventure Training Among Disaffected and At-Risk Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-Night Brecon Beacons Walking with Sightseeing Holiday

4-Night Brecon Beacons Walking with Sightseeing Holiday Tour Style: Walks with sightseeing Destinations: Brecon Beacons & Wales Trip code: BRWOD-4 Trip Walking Grade: 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Enjoy full days exploring the Brecon Beacons, combining the perfect mix of guided walks with sightseeing. Each holiday visits a selection of museums, historic buildings and attractions, whose entrance is optional. For 2021 holidays, please allow approximately £15 for admissions – less if you bring your English Heritage, CADW or National Trust cards. For 2022 holidays, all admissions to places of interest will be included in the price. That’s one less thing to remember! HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Discover the beauty of the dramatic Welsh countryside on guided walks • A trip on the Brecon Mountain Railway steam train to the end of the line to start your walk • Visit the bookshops of Hay-on-Wye and the Dan yr Ogof showcaves www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2. Walking is on lanes, paths, tracks and across open fields, rough pasture and moorland; with some short muddy sections. Walks are up to 5¼ miles (8½km) with 650 feet (200m) of ascent. ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: Craig Y Nos & Dan Yr Ogof Distance: 4 miles (6½km) Ascent: 500 feet (150m) In Summary: You start your walk in the upper Swansea valley and pass Craig y Nos, a 19th century castle once owned by opera diva Dame Adelina Patti, the Madonna of her time. -

4-Night Brecon Beacons Family Walking Adventure

4-Night Brecon Beacons Family Walking Adventure Tour Style: Family Walking Holidays Destinations: Brecon Beacons & Wales Trip code: BRFAM-4 1, 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The Brecon Beacons National Park protects an upland area of moorland, waterfalls and lakes and is designated an International Dark Sky Reserve. The area has a wonderful selection of walking options from level walks on high ridges to more challenging walks ascending the ‘Fans’ (peaks). There are gushing waterfalls (one of which you can walk behind!), impressive caves and even fossilised seabed, high in the hills. Walks take place in and around the park, ranging from easy strolls alongside rivers and past cascading waterfalls to more serious treks including to the top of Pen-y-Fan, South Wales’ highest peak. The Brecon Canal is a reminder of the area’s industrial heritage while ruined castles tell of bygone struggles for power. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Full Board en-suite accommodation. • Max guests in house: 57 • Family rooms: 7 • A full programme of walks guided by HF Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • All transport to and from the walks • Free Wi-Fi TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3. Level 1 - Short walks of 3-4 miles with up to 750 feet of ascent for little legs. Level 3 - Mid-range walks are 6-9 miles with up to 1,800 feet of ascent on undulating terrain. Level 5 - Longest walks are 9-12 miles with up to 3,150 feet of ascent in rugged upland areas for families with active teenagers. -

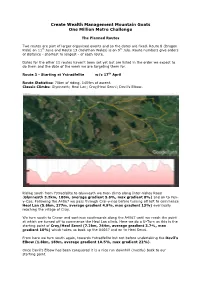

Create Wealth Management Mountain Goats One Million Metre Challenge

Create Wealth Management Mountain Goats One Million Metre Challenge The Planned Routes Two routes are part of larger organised events and so the dates are fixed. Route 8 (Dragon Ride) on 11th June and Route 13 (Velothon Wales) is on 9th July. Route numbers give orders of distance - shortest to longest - of each route. Dates for the other 11 routes haven't been set yet but are listed in the order we expect to do them and the date of the week we are targeting them for. Route 3 - Starting at Ystradfellte w/c 17th April Route Statistics: 70km of riding, 1459m of ascent. Classic Climbs: Glynneath; Heol Lan; Cray/Heol Senni; Devil's Elbow. Riding south from Ystradfellte to Glynneath we then climb along Inter-Valley Road (Glynneath 3.2km, 180m, average gradient 5.6%, max gradient 8%) and on to Pen- y-Cae. Following the A4067 we pass through Crai-y-nos before turning off left to commence Heol Lan (5.6km, 277m, average gradient 4.9%, max gradient 13%) eventually reaching the village of Cray. We turn south to Cnewr and continue southwards along the A4067 until we reach the point at which we turned off to commence the Heol Lan climb. Here we do a U-Turn as this is the starting point of Cray/Heol Senni (7.2km, 264m, average gradient 3.7%, max gradient 10%) which takes us back up the A4067 and on to Heol Senni. From here we turn south again, towards Ystradfellte but not before undertaking the Devil's Elbow (1.8km, 189m, average gradient 10.5%, max gradient 22%). -

The Taff Trail Is Just One of a Series of Trails Running Right Rivals the Best in the World

Feel Rested Other Trails in Merthyr Tydfil Aberfan Community Centre Merthyr has plenty of other trails on offer, Located in the centre of the village. so why not try one of these? The Open: 8am-8pm Mon - Fri and 9am – 4pm Sat & Sun. P Key Taff Trail (Route 8) Taff Trail Merthyr Tydfil Leisure Centre Trevithick Trail Located in Merthyr’s Leisure Village, just (Route 477) Merthyr Tydfil a short walk from the town centre. Celtic Trail (Route 4) Open: 8am-8pm Mon - Fri and 9am – 4pm Sat & Sun. Heads of the Valley Trail (Route 46) Steam Train Merthyr Town Centre St Tydfil’s Shopping centre provides a modern semi-covered pedestrian area with a diverse range of places to eat and drink. Various opening times. P Cyfarthfa Retail Park Various retail outlets including eateries. Open 9am – 8pm Mon – Sat, 11am -4pm Sun. MERTHYR TYDFIL M4 Cefn Coed Village A small car park is found on the High Street. Just look for the Church spire as it’s next door to it. The village has places to eat and drink. Looking for more? Open at various times. P visitmerthyr.co.uk Parkwood Outdoors Dolygaer Café For further information contact us at: A great stop at a stunning location for anyone visiting the National Park. You can also pick up needed repair tubes for your bikes. Email: [email protected] Open 9.30 – 5.30. Phone: 01685 725000 Merthyr Section 14 miles P Mail: VisitMerthyr, MerthyrTydfilCounty Borough Council, Tourism Dept. Largely TRAFFIC FREE There’s ample parking throughout the Borough with designated Civic Centre, Castle Street, National Cycle Route 8 car parks. -

Final Proposals Report

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF PART OF THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE COUNTY OF POWYS AND THE COUNTY BOROUGH OF MERTHYR TYDFIL IN THE AREA OF PONTSTICILL REPORT AND PROPOSALS LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF PART OF THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE COUNTY OF POWYS AND THE COUNTY BOROUGH OF MERTHYR TYDFIL IN THE AREA OF PONTSTICILL REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 4. DRAFT PROPOSALS 5. SUMMARY OF REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 6. ASSESSMENT 7. PROPOSALS 8. CONSEQUENTIAL ARRANGEMENTS 9. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 10. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT The Local Government Boundary Commission For Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail: [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk Brian Gibbons AM Minister for Social Justice and Local Government Welsh Assembly Government REVIEW OF PART OF THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE COUNTY OF POWYS AND THE COUNTY BOROUGH OF MERTHYR TYDFIL IN THE AREA OF PONTSTICILL REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 We the Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales (the Commission) have completed the review of County of Powys and the County Borough of Merthyr Tydfil in the area of Pontsticill as required by the Local Government Act 1972 as amended, (“the Act”). 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2.1 We propose a change be made to the boundary between the County of Powys and the County Borough of Merthyr Tydfil in the area of Pontsticill as illustrated on the map at Appendix B. -

King's College, Cambridge

King’s College, Cambridge Annual Report 2014 Annual Report 2014 Contents The Provost 2 The Fellowship 5 Major Promotions, Appointments or Awards 18 Undergraduates at King’s 21 Graduates at King’s 26 Tutorial 36 Research 47 Library and Archives 51 Chapel 54 Choir 57 Bursary 62 Staff 65 Development 67 Appointments & Honours 72 Obituaries 77 Information for Non Resident Members 251 While this incremental work can be accomplished within the College’s The Provost maintenance budget, more major but highly desirable projects, like the refurbishment of the Gibbs staircases and the roof and services in Bodley’s will have to rely on support apart from that provided by the endowment. 2 I write this at the end of my first year at The new Tutorial team under Perveez Mody and Rosanna Omitowoju has 3 THE PROVOST King’s. I have now done everything once begun its work. There are now five personal Tutors as well as specialist and am about to attend Alumni Weekend Tutors, essentially reviving a system that was in place until a few years ago. reunion dinners for the second time. It has It is hoped that the new system will reduce the pastoral pressure on the been a most exciting learning experience THE PROVOST Directors of Studies, and provide more effective support for students. getting to know the College. While I have not had much time for my own research I In the Chapel we have said farewell to our Dean, Jeremy Morris. Jeremy have had the opportunity to learn about came to the College from Trinity Hall in 2010, and after only too short a others’ interests, and have been impressed time returns to his former College as its Master. -

A465 Heads of the Valley Dualling Sections 5 and 6: Dowlais Top to Hirwaun

A465 Heads of the Valley Dualling Sections 5 and 6: Dowlais Top to Hirwaun PROOF OF EVIDENCE Economics Document WG 1.5.1 By John Siraut BSc, MSc, Dip Transport March 2018 Contents Section Page 1 Personal Statement ................................................................................... 1 2 Structure and Scope of Evidence .............................................................. 2 3 Policy and Guidance .................................................................................. 3 4 The Economic Context .............................................................................. 6 5 Approach taken to Economic Appraisal ................................................... 18 6 Estimation of Costs .................................................................................. 33 7 Appraisal Summary ................................................................................. 36 8 Wider Impacts ......................................................................................... 48 9 Social Impacts and Benefits .................................................................... 51 10 Community Benefits ................................................................................ 57 11 Conclusion ............................................................................................... 60 12 Declaration .............................................................................................. 63 Appendix A – Core Reporting Tables A465 Sections 5&6: Dowlais Top to Hirwaun Proof of Evidence – Economics -

ABSTRACT by Courtney Misich

ABSTRACT SOCIAL AND SPATIAL MOBILITY IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE: READING AND MAPPING LOWER CLASS TRAVEL ACCOUNTS OF THE 1790’s by Courtney Misich Through textual analysis and mapping of 1790s published travel accounts, this project examines how lower class individuals utilized the growing British Empire to expand their societal status and travel opportunities. Modeled on early novels of the mid-eighteenth century such as Robinson Crusoe and Pamela, these supposedly “true” travel accounts showed their protagonists using personal connections, patronage, and employment to overcome adversity and rise socially. Individuals demonstrated mobility through their public image, dress, and speech. Passing for middle class was difficult, although often achievable through education, conduct, and finances. A publicly available interactive map in ArcGIS Online was created. It shows the routes of travel, characteristics of the travelers’ social status, and quotations from the primary sources, allowing them to be compared. The interactive map was built from the travel accounts descriptions of their travels, social status, financial status, and employment through manual data entry. The map is designed to be accessible and appealing to a broad public, enlarging the audience beyond specialists in digital humanities. SOCIAL AND SPATIAL MOBILITY IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE: READING AND MAPPING LOWER CLASS TRAVEL ACCOUNTS OF THE 1790’s Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in History by Courtney Misich Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2017 Advisor: Dr. Renee Baernstein Reader: Dr. Lindsay Schakenbach Regele Reader: Ms. Robbyn Abbitt ©2017 Courtney Misich This thesis titled SOCIAL AND SPATIAL MOBILITY IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE: READING AND MAPPING LOWER CLASS TRAVEL ACCOUNTS OF THE 1790’s by Courtney Misich has been approved for publication by College of Arts and Science and Department of History ____________________________________________________ Dr. -

Explanatory Memorandum to the Preserved Counties of Powys and Mid Glamorgan (Changes in Area) Order 2010

Explanatory Memorandum to the Preserved Counties of Powys and Mid Glamorgan (Changes in Area) Order 2010 This Explanatory Memorandum has been prepared by Local Government Policy Division and is laid before the National Assembly for Wales in accordance with Standing Order 24.1. Minister’s Declaration In my view, this Explanatory Memorandum gives a fair and reasonable view of the expected impact of The Preserved Counties of Powys and Mid Glamorgan (Changes in Area) Order 2010. Carl Sargeant Minister for Social Justice and Local Government 11 January 2010 I. Description This Order gives effect to the recommendations of the Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales (the Commission) to realign part of the boundary between the Preserved Counties of Mid Glamorgan and Powys in the area of Pontsticill. II. Matters of special interest to the Subordinate Legislation Committee None III. Legislative Background Section 56 (1)(c) of the Local Government Act 1972 (the 1972 Act) provides that the Secretary of State may direct the Commission to conduct a review of one or more preserved counties or parts of such counties. Section 54(1A) of the 1972 Act states that the Commission may make proposals to the Secretary of State with regard to areas reviewed. Section 270 of the 1972 Act defines “preserved county” as any county in Wales as it stood immediately before the passing of the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, subject to any boundary changes. The purpose of the preserved counties in Wales is to define county areas for the purposes only of certain statutory ceremonial provisions, as listed in Schedule 2 of the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994. -

Talybont-On-Usk.Pdf

FINAL PROPOSALS Community No. B29 - TALYBONT-ON-USK Introduction 1. The north-east part of present community of Talybont-on-Usk lies in the valley of the river Usk where the main settlements in the community - the 2nd tier settlements of Pencelli and Talybont and the unclassified settlements of Scethrog and Llansantffraed - are located. To the north, the valley rises steeply to Allt yr Esgair, which provides a natural boundary between this community and the community of Llangors. In the south, the landscape of this community is defined by the more undulating moorland and heavily forested extents of the eastern Brecon Beacons. It is the high points of this area, at Bryn, Craig Pwllfa, Craig y Fan, Craig y Fan-ddu, Yr Allt, Waun-rydd and Tor y foel, that bound the southern part of community. Here the valley of the river Caerfanell and the Talybont Reservoir provide the main focus for habitation, with the small, unclassified settlement of Aber to the north of the reservoir. In its extreme southwest, this community falls to the upper reaches of the river Taf Fechan, where the community boundary follows a centre line through Pontsticill Reservoir on the northern outskirts of the County Borough of Merthyr Tydfil. The 2nd tier settlement of Pontsticill is partitioned by the community-county boundary, with some ten electors living in the community of Talybont-on-Usk. This settlement is some nine miles by narrow, unclassified county road from Talybont; it is less than three miles from the centre of Merthyr Tydfil. 2. The whole of this community lies within the Brecon Beacons National Park. -

Reservoir Passport Scheme Welcome to Welsh Water Reservoirs in the National Park

Brecon Beacons National Park Brecon Beacons Reservoir Passport Scheme Welcome to Welsh Water reservoirs in the National Park The Passport Scheme using the reservoirs on the same day, then Brecon Beacons National Park Authority (BBNPA) and 2 Passports are required. Dwˆr Cymru Cyfyngedig, trading as Dwˆr Cymru Welsh Group Safety Water (DCWW), in association with South Wales Outdoor Activity Providers Group (SWOAPG), have Groups are responsible for their own safety and should arranged the Passport Scheme (the Scheme) to enable be able to demonstrate upon request that risks are organised groups, many of which will be members being properly managed. This will include being led of SWOAPG, to access the following reservoirs for by suitably qualified and experienced canoe and kayak canoeing and kayaking - Pontsticill, Pentwyn, Usk and coaches who are able to effect emergency responses in Beacons Reservoirs (see maps provided). The Scheme any prevailing conditions. Canoes and kayaks will be fit is being administered by BBNPA. Any enquiries, for purpose and positively buoyant when flooded. applications or comments should be made to the All canoeists and kayakers will wear suitable personal BBNPA Headquarters in Brecon. Passport holders will safety equipment in line with current good practice. be notified of any changes to it. Powered safety boats will not be allowed. Leaders The Scheme was initially a one year Pilot (2013). must be current First Aid certificate holders. Groups In order for the Scheme to become successful and often will be AALS licensed. For clubs, educational and long-lasting, it is vital that Passport holders adhere to voluntary groups not within the scope of AALS, the the terms of the Scheme as set out in this document. -

Pontsticill Water Treatment Works

Focus products: Intercrete® 4820, Intercrete 4841 Pontsticill Water Location: Merthyr Tydfil, Wales Client: Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water Treatment Works Contractor: Stonbury Summary: Repair and protection of Case study secondary filters Background The solution Pontsticill Water Treatment Works, operated by Dŵr Cymru Intercrete products were chosen to reinstate the integrity of the Welsh Water, is located within the boundaries of Brecon Beacons secondary filters, due to their proven track record of protecting National Park. Drawing water from the Pontsticill Reservoir, structures subjected to aggressive water. Rapid application and it holds up to 3,400 million gallons for supply throughout South quick curing properties were also crucial, as repairs on the eroded Wales. The original Water Treatment Works was built in 1927 but concrete took place whilst the Water Treatment Works was still this was superseded by a new treatment plant completed in 1995, in operation. Intercrete 4820, a fully waterproof, engineering consisting of a DAF (Dissolved Air Flotation) plant and primary and quality fairing coat, was initially used as a levelling coat before the secondary rapid gravity filters. application of Intercrete 4841. This two component, waterborne cementitious modified polymer coating also benefits from Investigations in 1998 revealed that wash-water volumes were microsilica inclusion which reacts with lime to form insoluble greater than expected due to erosion of the concrete. Analysis hydrates, thereby protecting the concrete from leaching and of the concrete confirmed that an average of 5mm had been erosion with aggressive waters. eroded and aggregate was exposed due to the aggressive nature of the water. In addition to its excellent chemical resistance, a 2mm coating of Intercrete 4841 resists 10 bar hydrostatic pressure (100 metre head of water) and provides the same degree of waterproofing as 1000mm of good quality concrete.