A Microcosm of the Native American Struggle for Self-Determination and Tribal Sovereignty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Generative Syntax: a Cross-Linguistic Approach

Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Approach Michael Barrie Sogang University May 30, 2021 2 Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Introduction ľ 2021 by Michael Barrie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ (한국어: https: //creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.ko) by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only. If others modify or adapt the material, they must license the modified material under identical terms. Contents 1 Foundations of the Study of Language 13 1.1 The Science of Language .................................... 13 1.2 Prescriptivism versus Descriptivism .............................. 15 1.3 Evidence of Syntactic Knowledge ............................... 17 1.4 Syntactic Theorizing ....................................... 18 Key Concepts .............................................. 20 Exercises ................................................. 21 Further Reading ............................................ 22 2 The Lexicon and Theta Relations 23 2.1 Restrictions on lexical items: What words want and need ................ 23 2.2 Thematic Relations and θ-Roles ................................ 25 2.3 Lexical Entries ......................................... -

Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 239–266 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24976 Revised Version Received: 10 Mar 2021 #KeepOurLanguagesStrong: Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Kari A. B. Chew University of Oklahoma Indigenous communities, organizations, and individuals work tirelessly to #Keep- OurLanguagesStrong. The COVID-19 pandemic was potentially detrimental to Indigenous language revitalization (ILR) as this mostly in-person work shifted online. This article shares findings from an analysis of public social media posts, dated March through July 2020 and primarily from Canada and the US, about ILR and the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team, affiliated with the NEȾOL- ṈEW̱ “one mind, one people” Indigenous language research partnership at the University of Victoria, identified six key themes of social media posts concerning ILR and the pandemic, including: 1. language promotion, 2. using Indigenous languages to talk about COVID-19, 3. trainings to support ILR, 4. language ed- ucation, 5. creating and sharing language resources, and 6. information about ILR and COVID-19. Enacting the principle of reciprocity in Indigenous research, part of the research process was to create a short video to share research findings back to social media. This article presents a selection of slides from the video accompanied by an in-depth analysis of the themes. Written about the pandemic, during the pandemic, this article seeks to offer some insights and understandings of a time during which much is uncertain. Therefore, this article does not have a formal conclusion; rather, it closes with ideas about long-term implications and future research directions that can benefit ILR. -

The Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas: Walking a N~Rrow Path Between Two Worlds

THE CAYUGA CHIEF JACOB E. THOMAS: WALKING A N~RROW PATH BETWEEN TWO WORLDS Takeshi Kimura Faculty of Humanities Yamaguchi University 1677-1 Yoshida Yamaguchi-shi 753-8512 Japan Abstract I Resume The Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas (1922-1998) of the Six Nations Reserve, Ontario, worked on teaching and preserving the oral Native languages and traditions ofthe Longhouse by employing modern technolo gies such as audio- and video recorders and computers. His primary concern was to transmit and document them as much as possible in the face of their possible loss. Especially, he emphasized teaching the lan guage and religious knowledge together. In this article, researched and written before his death, I discuss the way he taught his classes, examine the educational materials he produced, and assess their features. I also examine several reactions toward his efforts among Native people. De son vivant Jacob E. Thomas (1922-1998), chef des Cayugas de la Reserve des Six Nations, en Ontario, a travaille a I'enseignement et a la preservation des langues parlees autochtones et des traditions du Long house. Pour ce faire, il a eu recours aux techniques d'enregistrement audio et video ainsi qu'a I'informatique. Devant Ie declin possible des langues et des traditions autochtones, son but principal a ete de les enregistrer et de les classifier pour les rendre accessible a tous. II a particulierement mis I'accent sur la necessite d'enseigner conjointement la langue et la religion. Dans cet article, dont la recherche et la redaction ont ete accomplies avant la mort de Thomas, j'examine son enseignement en ciasse de meme que Ie materiel pedagogique qu'il a cree et en evalue les caracteristiques. -

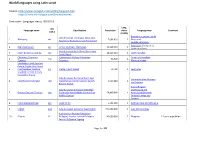

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

3115 Eblj Article 2 (Was 3), 2008:Eblj Article

Early Northern Iroquoian Language Books in the British Library Adrian S. Edwards An earlier eBLJ article1 surveyed the British Library’s holdings of early books in indigenous North American languages through the example of Eastern Algonquian materials. This article considers antiquarian materials in or about Northern Iroquoian, a different group of languages from the eastern side of the United States and Canada. The aim as before is to survey what can be found in the Library, and to place these items in a linguistic and historical context. In scope are printed media produced before the twentieth century, in effect from 1545 to 1900. ‘I’ reference numbers in square brackets, e.g. [I1], relate to entries in the Chronological Checklist given as an appendix. The Iroquoian languages are significant for Europeans because they were the first indigenous languages to be recorded in any detail by travellers to North America. The family has traditionally been divided into a northern and southern branch by linguists. So far only Cherokee has been confidently allocated to the southern branch, although it is possible that further languages became extinct before their existence was recorded by European visitors. Cherokee has always had a healthy literature and merits an article of its own. This survey therefore will look only at the northern branch. When historical records began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Northern Iroquoian languages were spoken in a large territory centred on what is now the north half of the State of New York, extending across the St Lawrence River into Quebec and Ontario, and southwards into Pennsylvania. -

Communication Across Canada's

YOUR PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS CONCIERGE COMMUNICATION ACROSS CANADA’S INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES COMMUNICATING INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES HOW wintranslationTM CAN HELP Did you know that there are over 60 Indigenous languages spoken in Canada today? Wintranslation is Canada’s leading specialist for professional translation services of Indigenous languages. For over 19 years, clients have relied on At Wintranslation we believe it is important to understand, recognize and celebrate these languages as part of Canada’s us to get the job done right for all of their specialized language translation WINTRANSLATION IS A diverse and rich heritage and culture. and revision needs. Whether it is a small translation, or a large and complex CERTIFIED SUPPLIER project in multiple Indigenous languages, our access to varied language BY THE CANADIAN translators, managed service delivery, and technical capabilities and Did you know that Indigenous language translation is much more complex than ABORIGINAL & MINORITY translating into and from other common languages? cultural understanding keep them coming back. Our focus on recruitment and retention of highly qualified translators, and capable and dedicated SUPPLIER COUNCIL The providers for Indigenous translation are extremely varied in languages and dialects in addition to work methods and project management service attributes directly to our clients’ satisfaction applications. There are many unique elements that should be taken into consideration for projects of this nature which (CAMSC) and successful outcomes. can -

Kanienâ•Žkã©Ha (Mohawk) (United States and Canada)

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Macaulay Honors College 2020 Kanien’kéha (Mohawk) (United States and Canada) - Language Snapshot Joseph Pentangelo CUNY Macaulay Honors College, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/mhc_pubs/2 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 19. Editor: Peter K. Austin Kanien’kéha (Mohawk) (United States and Canada) - Language Snapshot JOSEPH PENTANGELO Cite this article: Pentangelo, Joseph. 2020. Kanien’kéha (Mohawk) (United States and Canada) - Language Snapshot . Language Documentation and Description 19, 1-8. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/203 This electronic version first published: December 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ -

Nation to Nation

NATION TO NATION Neighbor to Neighbor Nation to Nation Readings About the Relationship of the Onondaga Nation with Central New York USA This booklet is dedicated to the continuing friendship between the peoples ofthe Haudenosaunee and Central New York. We share a difficult history but are united in our love for the land, water animals and plant life in our passion for justice and in our hope for the future generations. ------------------------Published by------------------------ Neighbors of the Onondaga Nation (NOON) Revised & Expanded 2014 The Edge of the Woods - Delivered by Chief Jake Swamp And sometimes when you went into some bushes that contained thorns and briars, then what we do now Today is we take them away from your clothes, we have arrived at the appointed time where so you can be comfortable while you are we are supposed to be with us. here in this place where our ancestors had made solemn Now sometimes what happens to people agreements. when they arrive from different directions as we have today And we rejoice in the fact perhaps recently we have experienced a that our brothers from Washington great loss in our family. and the United States representatives But because of the importance of our having that have arrived here to be with us, a clarity in our mind, have arrived safely to be here today. we now say these words to you: And now If you have tears in your eyes today because as to our custom in the olden times, of a recent loss, and as we do today also today we have brought a white cloth, whenever we receive visitors that enter and we use this to wipe away your tears, into our country so that your future will become clearer then we say these words to them: from this moment forward. -

LCSH Section O

O, Inspector (Fictitious character) O-erh-kʾun Ho (Mongolia) O-wee-kay-no Indians USE Inspector O (Fictitious character) USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE Oowekeeno Indians O,O-dimethyl S-phthalimidomethyl phosphorodithioate O-erh-kʾun River (Mongolia) O-wen-kʻo (Tribe) USE Phosmet USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE Evenki (Asian people) O., Ophelia (Fictitious character) O-erh-to-ssu Basin (China) O-wen-kʻo language USE Ophelia O. (Fictitious character) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Evenki language O/100 (Bomber) O-erh-to-ssu Desert (China) Ō-yama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Ōyama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) O/400 (Bomber) O family (Not Subd Geog) O2 Arena (London, England) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) Ó Flannabhra family UF North Greenwich Arena (London, England) O and M instructors USE Flannery family BT Arenas—England USE Orientation and mobility instructors O.H. Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) O2 Ranch (Tex.) Ó Briain family UF Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) BT Ranches—Texas USE O'Brien family Stacy Reservoir (Tex.) OA (Disease) Ó Broin family BT Reservoirs—Texas USE Osteoarthritis USE Burns family O Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) OA-14 (Amphibian plane) O.C. Fisher Dam (Tex.) USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine USE Grumman Widgeon (Amphibian plane) BT Dams—Texas Hukatere (N.Z.) Oa language O.C. Fisher Lake (Tex.) O-kee-pa (Religious ceremony) USE Pamoa language UF Culbertson Deal Reservoir (Tex.) BT Mandan dance Oab Luang National Park (Thailand) San Angelo Lake (Tex.) Mandan Indians—Rites and ceremonies USE ʻUtthayān hǣng Chāt ʻŌ̜p Lūang (Thailand) San Angelo Reservoir (Tex.) O.L. -

LCSH Section O

O, Inspector (Fictitious character) O-erh-kʾun Ho (Mongolia) O.T. Site (Wis.) USE Inspector O (Fictitious character) USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE OT Site (Wis.) O,O-dimethyl S-phthalimidomethyl phosphorodithioate O-erh-kʾun River (Mongolia) O-wee-kay-no Indians USE Phosmet USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE Oowekeeno Indians O., Ophelia (Fictitious character) O-erh-to-ssu Basin (China) O-wen-kʻo (Tribe) USE Ophelia O. (Fictitious character) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Evenki (Asian people) O/100 (Bomber) O-erh-to-ssu Desert (China) O-wen-kʻo language USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Evenki language O/400 (Bomber) O family (Not Subd Geog) Ō-yama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) Ó Flannabhra family USE Ōyama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) O and M instructors USE Flannery family O2 Arena (London, England) USE Orientation and mobility instructors O.H. Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) UF North Greenwich Arena (London, England) Ó Briain family UF Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) BT Arenas—England USE O'Brien family Stacy Reservoir (Tex.) O2 Ranch (Tex.) Ó Broin family BT Reservoirs—Texas BT Ranches—Texas USE Burns family O Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) OA (Disease) O.C. Fisher Dam (Tex.) USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine USE Osteoarthritis BT Dams—Texas Hukatere (N.Z.) OA-14 (Amphibian plane) O.C. Fisher Lake (Tex.) O.K. (The English word) USE Grumman Widgeon (Amphibian plane) UF Culbertson Deal Reservoir (Tex.) USE Okay (The English word) Oa language San Angelo Lake (Tex.) O-kee-pa (Religious ceremony) USE Pamoa language San Angelo Reservoir (Tex.) BT Mandan dance Oab Luang National Park (Thailand) BT Lakes—Texas Mandan Indians—Rites and ceremonies USE ʻUtthayān hǣng Chāt ʻŌ̜p Lūang (Thailand) Reservoirs—Texas O.L. -

Geography of American Indian Language Policy Thomas Pierre-Yves Brasdefer Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Sites of indigenous language practice : geography of American Indian language policy Thomas Pierre-Yves Brasdefer Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Brasdefer, Thomas Pierre-Yves, "Sites of indigenous language practice : geography of American Indian language policy" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1229. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1229 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SITES OF INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE PRACTICE: GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGE POLICY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography & Anthropology by Thomas Brasdefer Master, Université de Poitiers, 2005 August 2013 Acknowledgements There is a lot I have to acknowledge, and the benign recursion of this section is just too good to be omitted. Thank you for reading these lines: you are the Copernican revolution to this dissertation. None of this would have ever happened without the input of hundreds of people who took my phone calls, braved more communication breakdowns than I can count and talked to me for a minute or twelve; thank you, I cannot say for sure that I would have done the same for you.