Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bounding Around the Foundry We Find the Foundry Fascinating, and See Our Bells in Progress

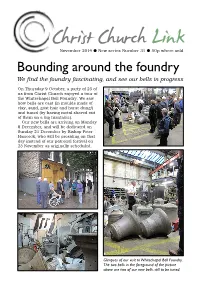

Christ Church Link November 2014 l New series Number 31 l 50p where sold Bounding around the foundry We find the foundry fascinating, and see our bells in progress On Thursday 9 October, a party of 25 of us from Christ Church enjoyed a tour of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. We saw how bells are cast (in moulds made of clay, sand, goat hair and horse dung!) and tuned (by having metal shaved out of them on a big turntable). Our new bells are arriving on Monday 8 December, and will be dedicated on Sunday 21 December by Bishop Peter Hancock, who will be presiding on that day instead of our patronal festival on 23 November as originally scheduled. Glimpses of our visit to Whitechapel Bell Foundry. The two bells in the foreground of the picture above are two of our new bells, still to be tuned. Improving access Mothers’ Union news Sylvia Ayers writes: Have YOU bought your MU Christmas Cards yet?? A colourful poster depicting them all is on the MU noticeboard, and, as with all good things, the early bird catches the worm. As usual, the cards come in packs of 10, so late ordering or a shortage of supplies may result in you missing out on a favourite choice. Do let Sylvia have your “cash with order” now if you would like to take advantage of our seasonal offer. Both Canon Angela and Margaret would like to thank everyone for their support at the MU Indoor Members’ Communion Service on October 17th, which ranged from welcoming our visitors to serving the refreshments, a task at which Angela (Verger) is particularly good! Both this and the meeting with our World-Wide President Lynn Temby at Monkton Combe School on 22nd, are very important events in the MU Calendar, so we thank everyone for their attendance and interest. -

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

Connections CONNOR CONNECTIONS ADVERTISEMENT

COCTOBER 2O009 The MagazNine of the DioceseN of Connor OR connections CONNOR CONNECTIONS ADVERTISEMENT TWO CONNOR CONNECTIONS BISHOP’S MESSAGE New parish Bring Christ to all grouping A new parish grouping came into in word and action existence in Connor on October 1. his edition of Connor Following the retirement from full Connections has a time ministry of the Rev Clifford particular focus on the Skillen, who had been rector of St Tworldwide church and I am Polycarp’s, Finaghy, for 13 years, the delighted to affirm and parishes of Finaghy and Upper encourage this. Malone (the Church of the Epiphany) in South Belfast have come together From my experience in parish in a new grouping. life, one of the lessons I learnt was the value of a link with The rector of the grouping is the Rev the worldwide church. It Garth Bunting, who has been rector helped the parish look beyond of Upper Malone since 2006. He has the parochial boundaries and been joined by the Rev Louise learn lessons from other Stewart as a non-stipendiary priest places. in the ministry team. Formerly, Louise served in that capacity in In the context of a link with St John’s, Malone. the Anglican Church in Kenya there was a greater Bishop Alan presents Bishop Jeremiah Taama of Kajiado Diocese Mr Skillen said he was ‘greatly awareness of the critical with a Connor shield during his recent visit to Kenya. blessed and privileged’ to have importance of the incarnation. In mission and not maintenance. Our served in St Polycarp’s and wished practical terms this meant the need mission is to bring Christ to all in word Garth and Louise every blessing as for the local church to find and action. -

Avenues of Honour, Memorial and Other Avenues, Lone Pines – Around Australia and in New Zealand Background

Avenues of Honour, Memorial and other avenues, Lone Pines – around Australia and in New Zealand Background: Avenues of Honour or Honour Avenues (commemorating WW1) Australia, with a population of then just 3 million, had 415,000 citizens mobilised in military service over World War 1. Debates on conscription were divisive, nationally and locally. It lost 60,000 soldiers to WW1 – a ratio of one in five to its population at the time. New Zealand’s 1914 population was 1 million. World War 1 saw 10% of its people, some 103,000 troops and nurses head overseas, many for the first time. Some 18,277 died in World War1 and another 41,317 (65,000: Mike Roche, pers. comm., 17/10/2018) were wounded, a 58% casualty rate. About another 1000 died within 5 years of 1918, from injuries (wiki). This had a huge impact, reshaping the country’s perception of itself and its place in the world (Watters, 2016). AGHS member Sarah Wood (who since 2010 has toured a photographic exhibition of Victoria’s avenues in Melbourne, Ballarat and France) notes that 60,000 Australian servicemen and women did not return. This left lasting scars on what then was a young, united ‘nation’ of states, only since 1901. Mawrey (2014, 33) notes that when what became known as the ‘Great War’ started, it was soon apparent that casualties were on a scale previously unimaginable. By the end of 1914, virtually all the major combatants had suffered greater losses than in all the wars of the previous hundred years put together. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

2012 QCEC Annual Report

2012 Annual Report 2012 CONTENTS QUEENSLAND CATHOLIC EDUCATION COMMISSION Message from the Chair 1 Report from the Executive Director 2 About the Commission 4 · Key Functions 4 Vision, Mission and Values 5 Members 6 Report on Strategic Priorities 2011-2013 7 QCEC COMMITTEE STRUCTURE 16 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 18 Executive Subcommittees Political Advisory Subcommittee 20 Catholic Education Week Subcommittee 21 Student Protection Subcommittee 22 CATHOLIC ETHOS, FORMATION AND RELIGIOUS EDUCATION COMMITTEE 23 INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMITTEE 24 EDUCATION COMMITTEE 25 Education Subcommittees Equity Subcommittee 26 Indigenous Education Subcommittee 27 Information and Communication Technologies Subcommittee 28 FINANCE COMMITTEE 29 Finance Subcommittee Capital Programs Subcommittee 32 OTHER School Transport Reference Committee 33 FINANCIAL STATEMENT 34 APPENDICES 36 I Committee Members 36 II QCEC Secretariat Structure and Staff 42 III Queensland Catholic Schools Statistics 43 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR In my report for last year I I am particularly grateful for the help and support Archbishop spoke of the Queensland Coleridge has given the QCEC during its funding travails, and floods of January 2011. At the I am most appreciative of the support I know I can rely on in time of writing this report, the future. His Grace believes passionately in the quality of Queensland has been ravaged Catholic education in this State, and the Commission shares again. Environmental disasters this passion with him. are stressful for all those There are a whole host of issues that have occupied the caught up by them and in Commission during 2012. Funding is just one of them, and them, emotionally and Mike Byrne's report touches on others. -

Church Bells Vol 3 (Bells and Bell Ringing)

N ovem ber 30, 1872.] Church Bells. 7 custom of the unreformed service continued, that the priest alone should repeat it; and the tradition has prevailed over the general rubric (1662), on BELLS AND BELL RINGING. the first occurrence of the Lord’s Prayer, ordering that the people should repeat it with the minister a wheresoever else it is used in D ivine S e r v i c e ’ Guild of Ringers. G . W. Si r ,— Can any of your readers kindly supply me with rules and directions Answers to Queries. for the formation of a Guild or Society amongst our Bell-ringers? I should Sin,—In answer to * Presbyter Hibernicus.’ The doctrinal tests of Metho also be glad to know of any suitable furniture for the ringing chamber.— T a u . dists appear to be Wesley’s Sermons, his Notes on the New Testament, and the Minutes of Conference. Change-ringing at Almondbury. I 11 answer to ‘ T. E.’ p. 619. I know 110 book so good as Flowers and O n Saturday, Nov. 16, the Society of Ringers rang seven true Treble Bob Festivals. (Barrett.) Published by Bivingtons, 5s. Peals, consisting of 720 changes each, making a total of 5040 changes, which In answer to 1 L. M.’ Advent is a season of devotion and penitence in they completed in 3 hrs. and 14 mins. The following were the peals rung, tended to prepare us for the celebration of our Lord’s Nativity, and to fit us and were ably conducted by W. Lodge :— London Scholars, Arnold’s Victory, to look forward with joyful hope to our Lord’s second coming. -

A Brief History of Rostrum Queensland 1937-2020

2020 A Brief History of Rostrum Queensland 1937-2020 Bill Smith 0 A BRIEF HISTORY OF ROSTRUM QUEENSLAND 1937 – 2020 Copyright © 2020 Bill Smith All rights reserved. NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA ISBN – 13: 978-0-646-83510-5 Brisbane, Qld, Australia No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. 1 The Rostrum Promise “I promise to submit myself to the discipline of this Rostrum club and to endeavour to advance its ideals and enrich its fellowship. I will defend freedom of speech in the community and will try at all times to think truly and speak clearly. I promise not to be silent when I ought to speak.” Sidney Wicks 1923. Dedicated to the memory of Freeman L.E. (Joe) Wilkins – A True Friend to Many 2 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Remarkable things do happen under trees! .................................................................................. 4 1930s .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1940s ........................................................................................................................................ 10 1950s ....................................................................................................................................... -

PN5544 C92 1989.Pdf

UG TilE UNIVERSI1Y OF QUEENSLAND UBRARIES LIBRARY · : UNDERGRADUATE . 4F19B8 · I! lJ6ll J!!6� tlliJ IJ - -- --- -- -- --- ---- - ...-- -----· �-------- -- �· ,.. , ; · - �· THE PRESS IN COLONIAL QUEENSLAND A SOCIAL AND POLITICAL HISTORY 1845-1875 Denis Cryle University of Queensland Press \ ' 100 r • I I , , ' � trCt�lr:'\ t.. I First published 1989 by University of Queensland Press, Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia © Denis Cryle 1989 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. The typeset text for this book was supplied by the author and has not been copyedited by the publisher. Printed in Australia by The Australian Print Group, Maryborough, Victoria Distributed in the USA and Canada by International Specialized Book Services, Inc., 5602 N.E. Hassalo Street, Portland, Oregon 97213-3640 Cataloguing in Publication Data National Library of Australia Cryle, Denis, 1949- . The press in colonial Queensland. Bibliography. Includes index. 1. Australian newspapers - Queensland - History - 19th century. 2. Press and politics - Queensland·_ History - 19th century. 3. Queensland - Social conditions - 1824-1900. I. Title. 079'.943 ISBN 0 7022 2181 3 Contents . Acknowledgments Vl List of T abies vii List of Maps vzzz . List of Illustrations lX Introduction: Redefining the Colonial Newspaper 1 Chapter 1 Press and Police: -

The Religious Life for Women in Australian Anglicanism, 1892-1995

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship THE BEST KEPT SECRET IN THE CHURCH : THE RELIGIOUS LIFE FOR WOMEN IN AUSTRALIAN ANGLICANISM, 1892-1995 BY GAIL ANNE BALL A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Studies in Religion University of Sydney (c) Gail Ball June 2000 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9 CHAPTER ONE 10 The Introduction of the Religious Life into the Church of England in the Nineteenth Century CHAPTER TWO 34 The Introduction of Dedicated Work for Women in the Anglican Church in the Australian Colonies CHAPTER THREE 67 The Establishment and Diversification of the Outreach of Religious Communities in Australia: 1892-1914 CHAPTER FOUR 104 From Federation to the Second World War: A Time of Expansion and Consolidation for the Religious Life CHAPTER FIVE 135 The Established Communities from the Second World War PAGE CHAPTER SIX The Formation of New Communities 164 between 1960 and 1995 CHAPTER SEVEN 187 An Appraisal of Spirituality particularly as it relates to the Religious Community CHAPTER EIGHT 203 Vocation CHAPTER NINE 231 Rules, Government and Customs CHAPTER TEN 268 The Communities Compared CHAPTER ELEVEN 287 Outreach - An Overview CHAPTER TWELVE 306 The Future CONCLUSION 325 BIBLIOGRAPHY 334 General Section 336 Archival Section 361 APPENDIX ONE 370 Professed Sisters of the Communities in Australia, 1995 Professed Sisters of Former Communities 386 Bush Church Aid Deaconesses -

THE ANGLICAN VOCATION in AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY by Randall

A Mediating Tradition: The Anglican Vocation in Australian Society Author Nolan, Randall Published 2008 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/159 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366465 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au A MEDIATING TRADITION: THE ANGLICAN VOCATION IN AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY by Randall Nolan B.A. (Hons.) (University of NSW) B.D. (University of Sydney) Grad. Dip. Min. (Melbourne College of Divinity) School of Arts Faculty of Arts Griffith University A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 ABSTRACT The Anglican Church of Australia agreed to a national constitution in 1962. Yet at a national level it is hardly a cohesive body with a sense of unity and common purpose. Historically, Australian Anglicanism developed along regional lines, with the result that diocesan separateness rather than national unity became enshrined as a foundational principle of Anglicanism in Australia. This study questions this fundamental premise of the Anglican tradition in Australia. It argues (1) that it is not a true reflection of the Anglican ethos, both in its English origins and worldwide, and (2) that it prevents Anglicanism in Australia from embracing its national vocation. An alternative tradition has been present, in fact, within Australian Anglicanism from the beginning, although it has not been considered to be part of the mainstream. Bishop Broughton, the first Anglican bishop in Australia, was deeply sensitive to the colonial context in which the Anglican tradition was being planted, and he adapted it accordingly. -

The Heraldry of the Hamiltons

era1 ^ ) of t fr National Library of Scotland *B000279526* THE Heraldry of the Ibamiltons NOTE 125 Copies of this Work have been printed, of which only 100 will be offered to the Public. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/heraldryofhamilsOOjohn PLATE I. THE theraldry of m Ibamiltons WITH NOTES ON ALL THE MALES OF THE FAMILY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ARMS, PLATES AND PEDIGREES by G. HARVEY JOHNSTON F.S.A., SCOT. AUTHOR OF " SCOTTISH HERALDRY MADE EASY," ETC. *^3MS3&> W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LIMITED EDINBURGH AND LONDON MCMIX WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. circulation). 1. "THE RUDDIMANS" {for private 2. "Scottish Heraldry Made Easy." (out print). 3. "The Heraldry of the Johnstons" of {only a few copies remain). 4. "The Heraldry of the Stewarts" Douglases" (only a few copies remain). 5. "The Heraldry of the Preface. THE Hamiltons, so far as trustworthy evidence goes, cannot equal in descent either the Stewarts or Douglases, their history beginning about two hundred years later than that of the former, and one hundred years later than that of the latter ; still their antiquity is considerable. In the introduction to the first chapter I have dealt with the suggested earlier origin of the family. The Hamiltons were conspicuous in their loyalty to Queen Mary, and, judging by the number of marriages between members of the different branches, they were also loyal to their race. Throughout their history one hears little of the violent deeds which charac- terised the Stewarts and Douglases, and one may truthfully say the race has generally been a peaceful one.