Introduction to Deep Beauty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Lattice Structure of Quantum Logic

BULL. AUSTRAL. MATH. SOC. MOS 8106, *8IOI, 0242 VOL. I (1969), 333-340 On the lattice structure of quantum logic P. D. Finch A weak logical structure is defined as a set of boolean propositional logics in which one can define common operations of negation and implication. The set union of the boolean components of a weak logical structure is a logic of propositions which is an orthocomplemented poset, where orthocomplementation is interpreted as negation and the partial order as implication. It is shown that if one can define on this logic an operation of logical conjunction which has certain plausible properties, then the logic has the structure of an orthomodular lattice. Conversely, if the logic is an orthomodular lattice then the conjunction operation may be defined on it. 1. Introduction The axiomatic development of non-relativistic quantum mechanics leads to a quantum logic which has the structure of an orthomodular poset. Such a structure can be derived from physical considerations in a number of ways, for example, as in Gunson [7], Mackey [77], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74]. Mackey [77] has given heuristic arguments indicating that this quantum logic is, in fact, not just a poset but a lattice and that, in particular, it is isomorphic to the lattice of closed subspaces of a separable infinite dimensional Hilbert space. If one assumes that the quantum logic does have the structure of a lattice, and not just that of a poset, it is not difficult to ascertain what sort of further assumptions lead to a "coordinatisation" of the logic as the lattice of closed subspaces of Hilbert space, details will be found in Jauch [8], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74], Received 13 May 1969. -

Relational Quantum Mechanics

Relational Quantum Mechanics Matteo Smerlak† September 17, 2006 †Ecole normale sup´erieure de Lyon, F-69364 Lyon, EU E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this internship report, we present Carlo Rovelli’s relational interpretation of quantum mechanics, focusing on its historical and conceptual roots. A critical analysis of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen argument is then put forward, which suggests that the phenomenon of ‘quantum non-locality’ is an artifact of the orthodox interpretation, and not a physical effect. A speculative discussion of the potential import of the relational view for quantum-logic is finally proposed. Figure 0.1: Composition X, W. Kandinski (1939) 1 Acknowledgements Beyond its strictly scientific value, this Master 1 internship has been rich of encounters. Let me express hereupon my gratitude to the great people I have met. First, and foremost, I want to thank Carlo Rovelli1 for his warm welcome in Marseille, and for the unexpected trust he showed me during these six months. Thanks to his rare openness, I have had the opportunity to humbly but truly take part in active research and, what is more, to glimpse the vivid landscape of scientific creativity. One more thing: I have an immense respect for Carlo’s plainness, unaltered in spite of his renown achievements in physics. I am very grateful to Antony Valentini2, who invited me, together with Frank Hellmann, to the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, in Canada. We spent there an incredible week, meeting world-class physicists such as Lee Smolin, Jeffrey Bub or John Baez, and enthusiastic postdocs such as Etera Livine or Simone Speziale. -

Why Feynman Path Integration?

Journal of Uncertain Systems Vol.5, No.x, pp.xx-xx, 2011 Online at: www.jus.org.uk Why Feynman Path Integration? Jaime Nava1;∗, Juan Ferret2, Vladik Kreinovich1, Gloria Berumen1, Sandra Griffin1, and Edgar Padilla1 1Department of Computer Science, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA 2Department of Philosophy, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA Received 19 December 2009; Revised 23 February 2010 Abstract To describe physics properly, we need to take into account quantum effects. Thus, for every non- quantum physical theory, we must come up with an appropriate quantum theory. A traditional approach is to replace all the scalars in the classical description of this theory by the corresponding operators. The problem with the above approach is that due to non-commutativity of the quantum operators, two math- ematically equivalent formulations of the classical theory can lead to different (non-equivalent) quantum theories. An alternative quantization approach that directly transforms the non-quantum action functional into the appropriate quantum theory, was indeed proposed by the Nobelist Richard Feynman, under the name of path integration. Feynman path integration is not just a foundational idea, it is actually an efficient computing tool (Feynman diagrams). From the pragmatic viewpoint, Feynman path integral is a great success. However, from the founda- tional viewpoint, we still face an important question: why the Feynman's path integration formula? In this paper, we provide a natural explanation for Feynman's path integration formula. ⃝c 2010 World Academic Press, UK. All rights reserved. Keywords: Feynman path integration, independence, foundations of quantum physics 1 Why Feynman Path Integration: Formulation of the Problem Need for quantization. -

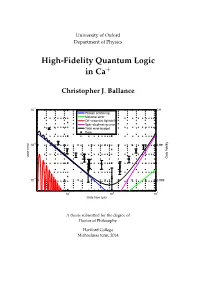

High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+

University of Oxford Department of Physics High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance −1 10 0.9 Photon scattering Motional error Off−resonant lightshift Spin−dephasing error Total error budget Data −2 10 0.99 Gate error Gate fidelity −3 10 0.999 1 2 3 10 10 10 Gate time (µs) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hertford College Michaelmas term, 2014 Abstract High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Michaelmas term 2014 Hertford College, Oxford Trapped atomic ions are one of the most promising systems for building a quantum computer – all of the fundamental operations needed to build a quan- tum computer have been demonstrated in such systems. The challenge now is to understand and reduce the operation errors to below the ‘fault-tolerant thresh- old’ (the level below which quantum error correction works), and to scale up the current few-qubit experiments to many qubits. This thesis describes experimen- tal work concentrated primarily on the first of these challenges. We demonstrate high-fidelity single-qubit and two-qubit (entangling) gates with errors at or be- low the fault-tolerant threshold. We also implement an entangling gate between two different species of ions, a tool which may be useful for certain scalable architectures. We study the speed/fidelity trade-off for a two-qubit phase gate implemented in 43Ca+ hyperfine trapped-ion qubits. We develop an error model which de- scribes the fundamental and technical imperfections / limitations that contribute to the measured gate error. -

Detailing Coherent, Minimum Uncertainty States of Gravitons, As

Journal of Modern Physics, 2011, 2, 730-751 doi:10.4236/jmp.2011.27086 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jmp) Detailing Coherent, Minimum Uncertainty States of Gravitons, as Semi Classical Components of Gravity Waves, and How Squeezed States Affect Upper Limits to Graviton Mass Andrew Beckwith1 Department of Physics, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China E-mail: [email protected] Received April 12, 2011; revised June 1, 2011; accepted June 13, 2011 Abstract We present what is relevant to squeezed states of initial space time and how that affects both the composition of relic GW, and also gravitons. A side issue to consider is if gravitons can be configured as semi classical “particles”, which is akin to the Pilot model of Quantum Mechanics as embedded in a larger non linear “de- terministic” background. Keywords: Squeezed State, Graviton, GW, Pilot Model 1. Introduction condensed matter application. The string theory metho- dology is merely extending much the same thinking up to Gravitons may be de composed via an instanton-anti higher than four dimensional situations. instanton structure. i.e. that the structure of SO(4) gauge 1) Modeling of entropy, generally, as kink-anti-kinks theory is initially broken due to the introduction of pairs with N the number of the kink-anti-kink pairs. vacuum energy [1], so after a second-order phase tran- This number, N is, initially in tandem with entropy sition, the instanton-anti-instanton structure of relic production, as will be explained later, gravitons is reconstituted. This will be crucial to link 2) The tie in with entropy and gravitons is this: the two graviton production with entropy, provided we have structures are related to each other in terms of kinks and sufficiently HFGW at the origin of the big bang. -

An Energy and Determinist Approach of Quantum Mechanics Patrick Vaudon

An energy and determinist approach of quantum mechanics Patrick Vaudon To cite this version: Patrick Vaudon. An energy and determinist approach of quantum mechanics. 2018. hal-01714971v2 HAL Id: hal-01714971 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01714971v2 Preprint submitted on 15 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. An energy and determinist approach of quantum mechanics Patrick VAUDON Xlim lab – University of Limoges - France 0 Table of contents First part Classical approach of DIRAC equation and its solutions Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 4 DIRAC equation ...................................................................................................................................... 9 DIRAC bi-spinors ................................................................................................................................. 16 Spin ½ of the electron .......................................................................................................................... -

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit Sasu Tuohino B. Sc. Thesis Department of Physical Sciences Theoretical Physics University of Oulu 2017 Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Classical network theory4 2.1 From electromagnetic fields to circuit elements.........4 2.2 Generalized flux and charge....................6 2.3 Node variables as degrees of freedom...............7 3 Hamiltonians for electric circuits8 3.1 LC Circuit and DC voltage source................8 3.2 Cooper-Pair Box.......................... 10 3.2.1 Josephson junction.................... 10 3.2.2 Dynamics of the Cooper-pair box............. 11 3.3 Transmon qubit.......................... 12 3.3.1 Cavity resonator...................... 12 3.3.2 Shunt capacitance CB .................. 12 3.3.3 Transmon Lagrangian................... 13 3.3.4 Matrix notation in the Legendre transformation..... 14 3.3.5 Hamiltonian of transmon................. 15 4 Classical dynamics of transmon qubit 16 4.1 Equations of motion for transmon................ 16 4.1.1 Relations with voltages.................. 17 4.1.2 Shunt resistances..................... 17 4.1.3 Linearized Josephson inductance............. 18 4.1.4 Relation with currents................... 18 4.2 Control and read-out signals................... 18 4.2.1 Transmission line model.................. 18 4.2.2 Equations of motion for coupled transmission line.... 20 4.3 Quantum notation......................... 22 5 Numerical solutions for equations of motion 23 5.1 Design parameters of the transmon................ 23 5.2 Resonance shift at nonlinear regime............... 24 6 Conclusions 27 1 Abstract The focus of this thesis is on classical dynamics of a transmon qubit. First we introduce the basic concepts of the classical circuit analysis and use this knowledge to derive the Lagrangians and Hamiltonians of an LC circuit, a Cooper-pair box, and ultimately we derive Hamiltonian for a transmon qubit. -

The World As Will and Quantum Mechanics

(https://thephilosophicalsalon.com) ! HOME (HTTPS://THEPHILOSOPHICALSALON.COM/) ABOUT (HTTPS://THEPHILOSOPHICALSALON.COM/ABOUT/) CONTACT US (HTTPS://THEPHILOSOPHICALSALON.COM/CONTACT/) DEBATES THE WORLD AS WILL AND JUL QUANTUM 22 2019 MECHANICS BY BENJAMIN WINTERHALTER (HTTPS://THEPHILOSOPHICALSALON.COM/AUTHOR/BENJAMININTERHALTER/) 4" SHARE 0# COMMENT 10♥ LOVE here is, unfortunately, no such thing as fate. If we accept that quantum mechanics— for all the strangeness associated with it—gives an accurate description of the T universe’s basic ontology, we should also accept that the will is real. The evidence for quantum mechanics is extremely strong, and physicists, including Alan Guth, David Kaiser, and Andrew Friedman (https://www.quantamagazine.org/physicists-are-closing-the-bell-test- loophole-20170207/), have closed some of the few remaining loopholes around the reality of quantum entanglement, a phenomenon wherein the state of a particle cannot be described independently of the state of at least one other. (Albert Einstein called entanglement “spooky action at a distance.”) But the existentially terrifying prospect of free will contains a shimmering surprise: In the conception of free will that’s compatible with quantum mechanics, exercises of the will—intentions or desires that lead to bodily actions—are fundamentally limited, finite, and constrained. In a word, entangled. According to the American philosopher John Searle’s 2004 book Freedom and Neurobiology, the fact of quantum indeterminacy—the ineradicable uncertainty in our knowledge of physical systems, first formulated by the German physicist Werner Heisenberg—does not guarantee that free will exists. Indeterminacy is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the belief that there is no such thing as fate. -

Theoretical Physics Group Decoherent Histories Approach: a Quantum Description of Closed Systems

Theoretical Physics Group Department of Physics Decoherent Histories Approach: A Quantum Description of Closed Systems Author: Supervisor: Pak To Cheung Prof. Jonathan J. Halliwell CID: 01830314 A thesis submitted for the degree of MSc Quantum Fields and Fundamental Forces Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Mathematical Formalism9 2.1 General Idea...................................9 2.2 Operator Formulation............................. 10 2.3 Path Integral Formulation........................... 18 3 Interpretation 20 3.1 Decoherent Family............................... 20 3.1a. Logical Conclusions........................... 20 3.1b. Probabilities of Histories........................ 21 3.1c. Causality Paradox........................... 22 3.1d. Approximate Decoherence....................... 24 3.2 Incompatible Sets................................ 25 3.2a. Contradictory Conclusions....................... 25 3.2b. Logic................................... 28 3.2c. Single-Family Rule........................... 30 3.3 Quasiclassical Domains............................. 32 3.4 Many History Interpretation.......................... 34 3.5 Unknown Set Interpretation.......................... 36 4 Applications 36 4.1 EPR Paradox.................................. 36 4.2 Hydrodynamic Variables............................ 41 4.3 Arrival Time Problem............................. 43 4.4 Quantum Fields and Quantum Cosmology.................. 45 5 Summary 48 6 References 51 Appendices 56 A Boolean Algebra 56 B Derivation of Path Integral Method From Operator -

Foundations of Mathematics and Physics One Century After Hilbert: New Perspectives Edited by Joseph Kouneiher

FOUNDATIONS OF MATHEMATICS AND PHYSICS ONE CENTURY AFTER HILBERT: NEW PERSPECTIVES EDITED BY JOSEPH KOUNEIHER JOHN C. BAEZ The title of this book recalls Hilbert's attempts to provide foundations for mathe- matics and physics, and raises the question of how far we have come since then|and what we should do now. This is a good time to think about those questions. The foundations of mathematics are growing happily. Higher category the- ory and homotopy type theory are boldly expanding the scope of traditional set- theoretic foundations. The connection between logic and computation is growing ever deeper, and significant proofs are starting to be fully formalized using software. There is a lot of ferment, but there are clear payoffs in sight and a clear strategy to achieve them, so the mood is optimistic. This volume, however, focuses mainly on the foundations of physics. In recent decades fundamental physics has entered a winter of discontent. The great triumphs of the 20th century|general relativity and the Standard Model of particle physics| continue to fit almost all data from terrestrial experiments, except perhaps some anomalies here and there. On the other hand, nobody knows how to reconcile these theories, nor do we know if the Standard Model is mathematically consistent. Worse, these theories are insufficient to explain what we see in the heavens: for example, we need something new to account for the formation and structure of galaxies. But the problem is not that physics is unfinished: it has always been that way. The problem is that progress, extremely rapid during most of the 20th century, has greatly slowed since the 1970s. -

Are Non-Boolean Event Structures the Precedence Or Consequence of Quantum Probability?

Are Non-Boolean Event Structures the Precedence or Consequence of Quantum Probability? Christopher A. Fuchs1 and Blake C. Stacey1 1Physics Department, University of Massachusetts Boston (Dated: December 24, 2019) In the last five years of his life Itamar Pitowsky developed the idea that the formal structure of quantum theory should be thought of as a Bayesian probability theory adapted to the empirical situation that Nature’s events just so happen to conform to a non-Boolean algebra. QBism too takes a Bayesian stance on the probabilities of quantum theory, but its probabilities are the personal degrees of belief a sufficiently- schooled agent holds for the consequences of her actions on the external world. Thus QBism has two levels of the personal where the Pitowskyan view has one. The differences go further. Most important for the technical side of both views is the quantum mechanical Born Rule, but in the Pitowskyan development it is a theorem, not a postulate, arising in the way of Gleason from the primary empirical assumption of a non-Boolean algebra. QBism on the other hand strives to develop a way to think of the Born Rule in a pre-algebraic setting, so that it itself may be taken as the primary empirical statement of the theory. In other words, the hope in QBism is that, suitably understood, the Born Rule is quantum theory’s most fundamental postulate, with the Hilbert space formalism (along with its perceived connection to a non-Boolean event structure) arising only secondarily. This paper will avail of Pitowsky’s program, along with its extensions in the work of Jeffrey Bub and William Demopoulos, to better explicate QBism’s aims and goals. -

An Argument for 4D Blockworld from a Geometric Interpretation of Non-Relativistic Quantum Mechanics Michael Silberstein1,3, Michael Cifone3 and W.M

An Argument for 4D Blockworld from a Geometric Interpretation of Non-relativistic Quantum Mechanics Michael Silberstein1,3, Michael Cifone3 and W.M. Stuckey2 Abstract We use a new distinctly “geometrical” interpretation of non-relativistic quantum mechanics (NRQM) to argue for the fundamentality of the 4D blockworld ontology. Our interpretation rests on two formal results: Kaiser, Bohr & Ulfbeck and Anandan showed independently that the Heisenberg commutation relations of NRQM follow from the relativity of simultaneity (RoS) per the Poincaré Lie algebra, and Bohr, Ulfbeck & Mottelson showed that the density matrix for a particular NRQM experimental outcome may be obtained from the spacetime symmetry group of the experimental configuration. Together these formal results imply that contrary to accepted wisdom, NRQM, the measurement problem and so-called quantum non-locality do not provide reasons to abandon the 4D blockworld implication of RoS. After discussing the full philosophical implications of these formal results, we motivate and derive the Born rule in the context of our ontology of spacetime relations via Anandan. Finally, we apply our explanatory and descriptive methodology to a particular experimental set-up (the so-called “quantum liar experiment”) and thereby show how the blockworld view is not only consistent with NRQM, not only an implication of our geometrical interpretation of NRQM, but it is necessary in a non-trivial way for explaining quantum interference and “non-locality” from the spacetime perspective. 1 Department of Philosophy, Elizabethtown College, Elizabethtown, PA 17022, [email protected] 2 Department of Physics, Elizabethtown College, Elizabethtown, PA 17022, [email protected] 3 Department of Philosophy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, [email protected] 2 1.