(SEMRU) Working Paper Series Operationalising Contemporary EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silver Strand Silverstrand Has a Safe, Shallow, Sandy Beach of Approximately 0.25Km Bounded on One Side by a Cliff and the Other by Rocks

Silver Strand Silverstrand has a safe, shallow, sandy beach of approximately 0.25km bounded on one side by a cliff and the other by rocks. It is particularly popular with and suitable for young families. It faces directly into Galway Bay giving spectacular views. There is a promenade with parking capacity for about 60 vehicles. It is suitable for swimming at low tide but the beach is largely covered during high tides. It is lifeguarded during the summer months. Blue Flag standard (2005). Barna Golf and Country Club Corbally, Barna, Co. Galway Telephone: +353 91 592677 Fax: +353 91 592674 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bearnagolfclub.com Located approx. 8km from Galway, and 3km north of Bearna village, this golf course is set in typical rugged Connemara countryside with fairways constructed between rocks and heather. The course was designed to suit all abilities. Bearna golf course is already being hailed as one of Ireland's finest. The inspired creativity of its designer R.J. Browne in the siting of tees and sand-based greens in the celebrated beauty of West of Ireland's Connemara landscape has produced a course of glamorously porportioned holes. Water comes into play at thirteen of the eighteen holes, each one boasting unique features which together test the golfer's total repertoire of skills. The final holes especially provide a spectacular finish to a satisfying and memorable experience. Caddy hire available. Dress code is neat & casual. Full canteen facilities available with full bar menu and restaurant. Course designed by Robert J Browne. Course length (m): 6174 Athenry Golf Club Palmerstown, Oranmore, Co. -

County Galway

Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 1 Report 2018 County Galway ISLAND BALLYMOE Conamara North LEA - 4 TEMPLETOGHERKILCROAN ADDERGOOLE BALLINASTACK INISHBOFIN TOBERADOSH BALLYNAKILL DUNMORE NORTH TOBERROE INISHBOFIN MILLTOWN BOYOUNAGH Tuam LEA - 7 DUNMORE SOUTH RINVYLE CARROWNAGUR GLENNAMADDY DOONBALLY RAHEEN CUSHKILLARY FOXHALLKILBENNAN CREGGS AN ROS KILTULLAGH CLEGGAN LEITIR BREACÁIN KILLEEN SILLERNA KILSHANVY CLONBERN CURRAGHMORE BALLYNAKILL AN FHAIRCHE SILLERNA CARROWREVAGH CLOONKEEN KILLERORAN BELCLARETUAM RURAL SHANKILL CLOONKEEN BEAGHMORE LEVALLY SCREGG AN CHORR TUAM URBAN CLIFDEN BINN AN CHOIRE AN UILLINN CONGA DONAGHPATRICK " BALLYNAKILL Clifden " DERRYLEA Tuam HILLSBROOK CLARETUAM KILLERERIN MOUNT BELLEW HEADFORDKILCOONA COOLOO KILLIAN ERRISLANNAN LETTERFORE CASTLEFFRENCH DERRYCUNLAGH KILLURSA BALLINDERRY MOYNE DOONLOUGHAN MAÍROS Oughterard CUMMER TAGHBOY KILLOWER BALLYNAPARK CALTRA " KILLEANYBALLINDUFF BUNOWEN ABBEY WEST CASTLEBLAKENEY AN TURLACH OUGHTERARD ABBEY EASTDERRYGLASSAUN CILL CHUIMÍN ANNAGHDOWN CLOCH NA RÓN KILMOYLAN MOUNTHAZEL CLONBROCK CLOCH NA RÓN WORMHOLE Ballinasloe LEA - 6 RYEHILL ANNAGH AHASCRAGH ABHAINN GHABHLA LISCANANAUN COLMANSTOWN EANACH DHÚIN DEERPARK MONIVEA BALLYMACWARD TULAIGH MHIC AODHÁIN LEACACH BEAG BELLEVILLE TIAQUIN KILLURE AN CNOC BUÍ CAMAS BAILE CHLÁIR CAPPALUSK SLIABH AN AONAIGH KILCONNELL LISÍN AN BHEALAIGH " Ballinasloe MAIGH CUILINNGALWAY RURAL (PART) SCAINIMH LEITIR MÓIR GRAIGABBEYCLOONKEEN KILLAAN BALLINASLOE URBAN CEATHRÚ AN BHRÚNAIGHAN CARN MÓR BALLINASLOE RURAL LEITIR MÓIR CILL -

Studies in Irish Craniology (Aran Islands, Co. Galway)

Z- STUDIES IN IRISH ORANIOLOGY. (ARAN ISLANDS, CO. GALWAY.) BY PROFESSOR A. C. HADDON. A PAPER Read before the ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY, December 12, 1892; and “ Reprinted from the Procrrimnos,” 3rd Ser., Vol, II.. No. 5. \_Fifty copies only reprinted hy the Academy for the Author.] DUBLIN: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, BY PONSONBY AND WELDRICK, PKINTBRS TO THB ACAHRMY. 1893 . r 759 ] XXXVIII. STUDIES IN lEISH CKANIOLOGY: THE ARAN ISLANDS, CO. GALWAY.* By PROFESSOR A. C. HADDON. [Eead December 12, 1892.] The following is the first of a series of communications which I pro- pose to make to the Academy on Irish Craniology. It is a remarkable fact that there is scarcely an obscure people on the face of the globe about whom we have less anthropographical information than we have of the Irish. Three skulls from Ireland are described by Davis and Thumam in the “Crania Britannica” (1856-65); six by J. Aitken Meigs in his ‘ ‘ Catalogue of Human Crania in the Collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia ” two by J. Van der Hoeven (1857) ; in his “ Catalogus craniorum diversarum gentium” (1860); thirty- eight (more or less fragmentary), and five casts by J. Barnard Davis in the “Thesaurus craniorum” (1867), besides a few others which I shall refer to on a future occasion. Quite recently Dr. W. Frazer has measured a number of Irish skulls. “ A Contribution to Irish Anthropology,” Jour. Roy. Soc. Antiquarians of Ireland, I. (5), 1891, p. 391. In addition to three skuUs from Derry, Dundalk, and Mary’s Abbey, Dublin, Dr. -

Bus-Eireann-Route-350.Pdf

TIMETABLE EFFECTIVE SUNDAY 11th MAY 2014. Table No. GALWAY − KINVARA − DOOLIN − CLIFFS OF MOHER − ENNIS 350 MONDAY TO SATURDAY SUNDAYS & PUBLIC HOLIDAYS SERVICE NUMBER 350 350 350 350 350 350 350 350 350 350 350 350 ‰ ˆ SX ‰ ˆ Galway (Bus Station) dep. .... 0800 1000 .... 1300 1500 1700 1800 .... 0800 1000 .... 1300 1500 .... .... Dublin Rd (GMIT) .... 0806 1006 .... 1306 1506 1710 1810 .... 0806 1006 .... 1306 1506 .... .... Oranmore (Oran Town Centre) .... 0815 1015 .... 1315 1515 1720 1820 .... 0815 1015 .... 1315 1515 .... .... Clarenbridge (Church) .... 0823 1023 .... 1323 1523 1728 1828 .... 0823 1023 .... 1323 1523 .... .... Kilcolgan (N67 Crossroad) .... 0826 1026 .... 1326 1526 1731 1831 .... 0826 1026 .... 1326 1526 .... .... Ballinderreen (Westbound) .... 0829 1029 .... 1329 1529 1745 1834 .... 0829 1029 .... 1329 1529 .... .... Kinvara (Square) .... 0835 1035 .... 1335 1535 1800 1840 .... 0835 1035 .... 1335 1535 .... .... New Quay (Opp Linnanes Bar) .... .... .... 1851 .... .... .... .... Bellharbour (Burren Cottages) .... 0847 1047 .... 1347 1547 .... 1855 .... 0847 1047 .... 1347 1547 .... .... Ballyvaughan (Opp Spar) .... 0855 1055 .... 1355 1555 .... 1905 .... 0855 1055 .... 1355 1555 .... .... Blackhead Lighthouse (southbound) .... 0907 1107 .... 1407 1607 .... 1917 .... 0907 1107 .... 1407 1607 .... .... Munough Bridge (southbound) .... 0909 1109 .... 1409 1609 .... 1919 .... 0909 1109 .... 1409 1609 .... .... Fanore Cross (ODonoghues Pub) .... 0912 1112 .... 1412 1612 .... 1922 .... 0912 1112 .... 1412 1612 .... .... Ballinalacken Castle (Main Gate) .... 0922 1122 .... 1422 1622 .... 1932 .... 0922 1122 .... 1422 1622 .... .... Lisdoonvarna (Burkes Garage) 0745 0930 1130 .... 1430 1630 .... 1940 .... 0930 1130 .... 1430 1630 .... .... Doolin (Doolin Hostel) 0800 0945 1145 .... 1445 1645 .... 1955 .... 0945 1145 .... 1445 1645 .... .... Doolin (Camp Site) 0805 0950 1150 .... 1450 1650 .... .... .... 0950 1150 .... 1450 1650 .... 1850 Doolin (Fisher Street House) 0812 0957 1157 .... 1457 1657 .... .... .... 0957 1157 .... 1457 1657 ... -

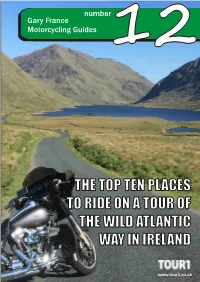

Guide 12 Wild Atlantic

number Gary France Motorcycling Guides 12 THE TOP TEN PLACES TO RIDE ON A TOUR OF THE WILD ATLANTIC WAY IN IRELAND www.tour1.co.uk 1. Doolough Pass The pass is on the R335 road, between Cregganbaun and Delphi, in County Mayo. It Introduction is a good riding road set between scenic mountains and beside a stunning lake. The Wild Atlantic Way is the coast road Doolough Pass is shown on the cover of this on the west coast of Ireland and what a guide. stunning place it is to ride! As it has become more popular in recent years, I have often been asked what are the best parts of the road to ride. Here are my top ten, in order of north to south. Other people may have other thoughts about places that are equally as good, but these are my favourites that I have ridden and seen for myself. 2. Sky Road, Clifden Immediately to the west of Clifden in County Gary France. Galway is Sky Road which runs around a peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean. The Sky Road route takes you up among the hills overlooking Clifden Bay and its offshore islands, Inishturk and Turbot. Be sure to ride around the whole Sky Road loop and I have found clockwise to be the best direction. www.tour1.co.uk 1 3. The Connemara 5. Connor Pass The Connemara is a district on the west coast Connor Pass runs diagonally across the Dingle of Ireland which runs broadly from Killary Peninsula, in County Kerry. -

Inspector's Report PL07.248891

Inspector’s Report PL07.248891 Development Water abstraction and ancillary works Location Loch an Mhuillin, Gorumna Island, Co. Na. Gaillimhe Planning Authority Galway County Council Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 17/49 Applicant(s) Bradán Beo Teo Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Refuse permission Type of Appeal First Party Appellant(s) Bradán Beo Teo Observer(s) Udaras Na Gaeltachta Peter Sweetman & Associates Coiste Fostaiochta Iorras Aithneach Inland Fisheries Ireland Date of Site Inspection 13th October 2017 PL07.248891 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 34 Inspector Rónán O’Connor PL07.248891 Inspector’s Report Page 2 of 34 Contents 1.0 Site Location and Description .............................................................................. 4 2.0 Proposed Development ....................................................................................... 4 3.0 Planning Authority Decision ................................................................................. 5 3.1. Decision ........................................................................................................ 5 3.2. Planning Authority Reports ........................................................................... 5 3.3. Prescribed Bodies ......................................................................................... 6 3.4. Third Party Observations .............................................................................. 7 4.0 Planning History ................................................................................................ -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Kilkieran Bay and Islands SAC (Site Code: 2111)

NPWS Kilkieran Bay and Islands SAC (site code: 2111) Conservation objectives supporting document - marine habitats and species Version 1 January 2014 Introduction Kilkieran Bay and Islands SAC is designated for the Annex I qualifying interests of Large shallow inlets and bays, Mudflats and sandflats not covered by seawater at low tide and Reefs (Figures 1, 2 and 3) and the Annex II species Phoca vitulina (harbour seal, also known as the common seal). The Annex I habitat Large shallow inlets and bays is a large physiographic feature that may wholly or partly incorporate other Annex I habitats including mudflats and sandflats and reefs within its area. Intertidal and subtidal surveys of Kilkieran Bay and Islands SAC were undertaken in 2001 and 2002 (SSI, 2003) and 2010 (APEM, 2011; Aquafact, 2011a; Aquafact, 2011b). In 2005, a dive survey was carried out to map the sensitive communities at this site (MERC, 2005). All of these data, together with data from the BioMar survey carried out in 1997 (Picton & Costello, 1997) and a Marine Institute oyster survey in winter 2010-2011 (Tully & Clarke, 2012), were used to investigate the physical and biological structure of this site. In addition to the records compiled from historical Wildlife Service site visits and regional surveys (Summers et al., 1980; Warner, 1983; Harrington, 1990; Doyle, 2002; Lyons, 2004), a comprehensive survey of the Irish harbour seal population was carried out in 2003 (Cronin et al, 2004). A repeat survey was conducted in the west of Ireland in 2011 and the associated distribution data have been included in this document. -

Telepsychiatry': Keeping a Link with an Island

BRIEFINGS 'Telepsychiatry': keeping a link with an island L Mannion, T.J. Fahy, C. Duffy, M, Broderick and E. Gethins quality. We report on the pilot phase of a video conferencing link between a psychiatric depart ment and an island located within its catchment area. The study The three Aran Islands, Inishmore, Inisheer, and Inishmean, located off the west coast of Ireland, are included as part of a sector area of the West Galway Psychiatric Service. The population of these islands have been greatly affected by emigration. We have estimated that there are 53 psychiatric patients permanently resident on the three islands. The majority of this group suffer from major psychiatric disorders requiring continual monitoring. The population of the Figure 1. Aran Islands. islands increases enormously during the sum mer months due to the influx of tourists. Medical care is provided by one general practitioner (GP). with a public health nurse resident on each Telemedicine' has been defined as the delivery of island. Psychiatric care is provided by periodic health care where the patient and health profes visits by the community services team of the sional are at different locations (McLaren & Ball, West Galway service. An out-patient clinic is held 1995), and in recent years has come to be on the main island, Inishmore, every two months regarded as the use of telecommunications and every three to four months on the smaller technology for medical applications. Telepsy- islands. A community psychiatric nurse (CPN) chiatry' is the branch of 'telemedicine' that visits Inishmore every month and each of the focuses on mental health applications. -

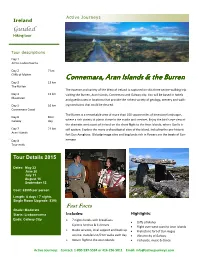

IR Connemara Burren GH.Pub

Active Journeys Ireland Guided Hiking tour Tour descriptions Day 1 Arrive Lisdoonvarna Day 2 7 km Cliffs of Moher Connemara, Aran Islands & the Burren Day 3 13 km The Burren The essence and variety of the West of Ireland is captured on this three centre-walking trip Day 4 13 km vising the Burren, Aran Islands, Connemara and Galway city. You will be based in hotels Maumeen and guesthouses in locaons that provide the richest variety of geology, scenery and walk- Day 5 16 km ing condions that could be desired. Connemara Coast The Burren is a remarkable area of more than 100 square miles of limestone landscape, Day 6 Rest Galway day where a rich variety of plants thrive in the cracks and crevices. Enjoy the bird’s eye view of the dramac west coast of Ireland on the short flight to the Aran Islands, where Gaelic is Day 7 21 km sll spoken. Explore the many archaeological sites of the island, including the pre-historic Aran Islands fort Dun Aonghasa. Old pilgrimage sites and bog lands rich in flowers are the treats of Con- Day 8 nemara. Tour ends Tour Details 2015 Dates: May 23 June 20 July 11 August 15 September 12 Cost: $2095 per person Length: 8 days / 7 nights Single Room Upgrade: $395 Fast Facts Grade: Moderate Starts: Lisdoonvarna Includes: Highlights: Ends: Galway City • 7 nights hotels with breakfasts • Cliffs of Moher 6 picnic lunches & 6 dinners • Flight over west coast to Aran Islands • Guide services, local support and back up • Prehistoric fort of Dun Aegus service, transfers to/from walks each day • Vibrant city of Galway • Return flight to the Aran Islands • Irish pubs, music & dance Acve Journeys Contact: 1-800-597-5594 or 416-236-5011 Email: [email protected] Inerary Day 1 Arrival Arrival at accommodaon in Lisdoonvarna, renowned for tradional Irish music. -

A Case Study of Stone Forts at Cliff-Top Locations in the Aran Islands, Ireland

GEA(Wiley) RIGHT BATCH Short Contribution: Marine Erosion and Archaeological Landscapes: A Case Study of Stone Forts at Cliff-Top Locations in the Aran Islands, Ireland D.Michael Williams Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland Two massively constructed stone forts exist on the edge of vertical coastal cliffs on the Aran Islands, Ireland. One of these, Dun Aonghusa, contains evidence of occupation that predates the main construction phases of the walls and broadly spans a time interval of 3300–2800 yr B.P. The other fort, Dun Duchathair, has been termed a promontory fort because its remaining wall crosses the neck of a small promontory marginal to the cliffs. Estimates of past rates of marine erosion in this part of Ireland may be made both by analogy with studies in other areas and comparison with present day rates of marine erosion. A working model for erosion rates of approximately 0.4m of coastal recession per annum is suggested. By applying this rate to the cliffs of the Aran Islands, it can be shown that, assuming a construction date of approximately 2500 yr B.P. for these forts, they were originally built at a considerable distance from the coastline. Thus Dun Duchathair was not a promontory fort. The earliest recorded habitation at Dun Aonghusa, dated to the middle of the Bronze Age, was, therefore, at some distance inland and not on an exposed 70 m high cliff on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. ᭧ 2004Wiley Periodicals, Inc. INTRODUCTION At a period of widespread rise in relative sea-level in many parts of the world, the present-day landscapes of archaeological sites may be misleading due to marine erosion. -

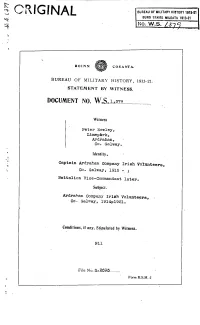

BMH.WS1379.Pdf

ROINN COSANTABUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,379 Witness Peter Howley, Limepark, Ardrahan, Co. Galway. Identity. Captain Ardrahan Company Irish Volunteers, Co. Gaiway, 1915 -; Battalion Vice-Commandant later. Subject. Ardrahan Company Irish Volunteers, Co. Galway, 1914-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2693 Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY PETER HOWLEY, Limepark, Ardrahan, Co. Gaiway. I was born in Limepark in the parish of Peterswell on the 12th April, 18914, and was educated at Peterswell National School until I reached the age of about sixteen years. I then left school and went to work on my father's farm at Limepark about the year 1910. At that time conditions were very unsettled in my part of County Galway. Holdings were small and rents were very high There were many evictions for non-payment of rent. The landlords had little mercy on the tenants who could not afford to pay the high rents, and evictions were carried out with the assistance of the R.I.C., a most unpopular force for that reason. I remember that in the year 1909 my four brothers were working on my uncle's farm at Capard. One evening on their way home to Limepark from capard they stopped at the village of Peterswell for refreshments. On leaving Hayes's publichouse one of my brothers saw an R.I.C. man with his ear to the door in a listening attitude. My brother struck him and he ran to the barrack, which my brothers had to pass on their way home.