Bill Reynolds Transcript.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Action Plan for Multiple Species at Risk in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series Action Plan for Multiple Species at Risk in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide Black-footed Ferret Burrowing Owl Eastern Yellow-bellied Racer Greater Sage-Grouse Prairie Loggerhead Shrike Mormon Metalmark Mountain Plover Sprague’s Pipit Swift Fox 2016 Recommended citation: Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2016. Action Plan for Multiple Species at Risk in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. xi + 127 pp. For copies of the action plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, recovery strategies, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: Landscape photo: South of the Divide, Jones Peak © Native Plant Society, C. Neufeld; Prairie Loggerhead Shrike © G. Romanchuck; Mormon Metalmark © R.L. Emmitt; Swift Fox © Environment and Climate Change Canada, G. Holroyd; Yellow-bellied Racer © Environment and Climate Change Canada, A.Didiuk Également disponible en français sous le titre « Plan d’action pour plusieurs espèces en péril dans le sud-ouest de la Saskatchewan – South of the Divide [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2016. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca Action Plan for Multiple Species in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide 2016 Preface The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996)2 agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. -

Govenlock News

Volume 28, Issue 12 January 22, 2015 Next Issue—February 12, 2015 The Reno Reader Informing the residents of reno since 1986 PUBLISHED BY CONSUL MUSEUM INCORPORATED W. G. Jones and A. R. Rowe with a crew Govenlock News of men are putting up ice for the coming (Taken from Maple Creek News season. February 12, 1914) Proud to Sponsor the Consul Museum (online at http://sabnewspapers.usask.ca) B. A. Jahn, our thrifty rancher, is busy The Govenlock Commercial Club gave breaking horses. Mr. Jahn has sold a number of horses to farmers in this area. Consul Grocery one of their popular dancing parties last Store Monday evening. The purpose of these 306-299-2011 parties is to raise money to build a hall. Arthur Sanford has just completed his Raymond Olmsted Among those present were Mr. and Mrs. new house and is getting comfortably Manager settled there. Weekdays: 9-6 W. X. Wright from “The Meadows”, Mr. Consul Farm Supply and Mrs. D. A. Hammond of Stormfield 306-299-2022 Ranch, Mr. and Mrs. Chas. Kennedy, Wm. Govenlock has opened a general Scott Amundson - Manager blacksmith and repair shop. He has se- Weekdays: 8-5:30 Kelvinhurst, D. C. and Gordon McMil- Saturday: 8-12, 1-5 lan, Kelvinhurst, Will McRae and sister, cured the services of Alex Skinner who is MEMBER OWNED Battle Creek, Mr. and Mrs. Ned McKay, one of the best horse shoers in Canada. Six Mile, Mrs. Marshall and family, Bat- Besides the [?] acres sold by W. T. Jones REAMER TRUCKING tle Creek, Paul Hester and sisters of Wil- low Creek and many others. -

Spring Runoff Highway Map.Pdf

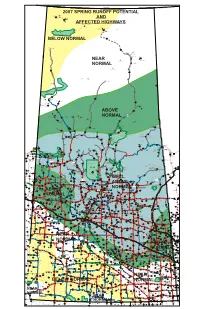

NUNAVUT TERRITORY MANITOBA NORTHWEST TERRITORIES 2007 SPRING RUNOFF POTENTIAL Waterloo Lake (Northernmost Settlement) Camsell Portage .3 999 White Lake Dam AND Uranium City 11 10 962 19 AFFECTEDIR 229 Fond du Lac HIGHWAYS Fond-du-Lac IR 227 Fond du Lac IR 225 IR 228 Fond du Lac Black Lake IR 224 IR 233 Fond du Lac Black Lake Stony Rapids IR 226 Stony Lake Black Lake 905 IR 232 17 IR 231 Fond du Lac Black Lake Fond du Lac ATHABASCA SAND DUNES PROVINCIAL WILDERNESS PARK BELOW NORMAL 905 Cluff Lake Mine 905 Midwest Mine Eagle Point Mine Points North Landing McClean Lake Mine 33 Rabbit Lake Mine IR 220 Hatchet Lake 7 995 3 3 NEAR Wollaston Lake Cigar Lake Mine 52 NORMAL Wollaston Lake Landing 160 McArthur River Mine 955 905 S e m 38 c h u k IR 192G English River Cree Lake Key Lake Mine Descharme Lake 2 Kinoosao T 74 994 r a i l CLEARWATER RIVER PROVINCIAL PARK 85 955 75 IR 222 La Loche 914 La Loche West La Loche Turnor Lake IR 193B 905 10 Birch Narrows 5 Black Point 6 IR 221 33 909 La Loche Southend IR 200 Peter 221 Ballantyne Cree Garson Lake 49 956 4 30 Bear Creek 22 Whitesand Dam IR 193A 102 155 Birch Narrows Brabant Lake IR 223 La Loche ABOVE 60 Landing Michel 20 CANAM IR 192D HIGHWAY Dillon IR 192C IR 194 English River Dipper Lake 110 IR 193 Buffalo English River McLennan Lake 6 Birch Narrows Patuanak NORMAL River Dene Buffalo Narrows Primeau LakeIR 192B St.George's Hill 3 IR 192F English River English River IR 192A English River 11 Elak Dase 102 925 Laonil Lake / Seabee Mine 53 11 33 6 IR 219 Lac la Ronge 92 Missinipe Grandmother’s -

St. Mary and Milk Rivers

Report to THE INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMlllISSION THE DIVISION AND USE MADE OF THE WATERS OF ST. MARY AND MILK RIVERS J. D. McLEOD representing Canada and L. B. LEOPOLD representing United States International Joint Commission, Washington, DOCo ,, and Ottawa, Ontario. Gentlemen: In compliance with the Provisions of Clause VIII (c) of your Order of the 4th October, 1921, directing the division of the waters of St. Mary and Milk Rivers between the United States and Canada, we are transmitting herewith a report on the operations during the irrigation season ended October 31, 1960. ~ccreditedOfficer of Her Majesty. L, B. Leopold Accredited Officer of the United States. Mqrch 17, 9 1961 . (date) Letter of Transmittal to the Commission Introduction ................ 1 Water Supply - St. ~YaryRiver ........... 2 Milk River - and its Eastern Tributaries .......... 3 Division of Water - St. Ivkry River ........ 4 Milk River ............ 7 Eastern Tributaries of Milk River .... 8 ~e'scri~tionof Tables ............. 10 Appendix ................. 12 TABLES Table No. , Natural Flow of St. Mary River at International Boundary and its Division between Canada and the United States ................ 1 Sumnary of Mean Monthly Natural Flow of St. Mary River at International Boundary ............ Summary of ?.lean Monthly United States Share of Natural Flow of St. 1kry River at International Boundary .... Summary of Mean Monthly Canadian Share of Natural Flow of St. Mary River at International Boundary ....... Division of Flow of St. Hary River and its use by Canada Division of .Flows of St. Mary and Milk Rivers and their usebytheunitedstates ............ Determination of Natural Flow of Battle Creek at the International Boundary ............. Determination of Natural Flow of Frenchman River at the International Boundary ......... -

February 27, 2014 Next Issue—March 13, 2014

Volume 27, Issue 14 February 27, 2014 Next Issue—March 13, 2014 The Reno Reader Informing the residents of reno since 1986 PUBLISHED BY CONSUL MUSEUM INCORPORATED WE’VE ALWAYS HAD FUN TIMES HERE! Consul’s 100th Anniversary is coming up fast, and we are all look- ing forward to the fun time it will be, the old friends we will enjoy Proud to Sponsor the Consul Museum seeing, and the memories we will share. Consul Grocery Store It seems, not surprisingly, that people from here have always 299-2011 known how to have fun. Here are samples, taken from Our Side Raymond Olmsted Manager of the Hills history books. Weekdays: 9-6 Consul Farm Supply 299-2022 “We were thrilled with the silent home movies that were made by Scott Amundson - Manager Weekdays: 8-5:30 Kurt Browatzke. He showed them at his home, and later at the Saturday: 8-12, 1-5 Merryflat School when everyone gathered there. They were MEMBER OWNED mostly of their cows, building their silo and farm work. He could speed up the machine and the cows would be eating so fast, and REAMER TRUCKING we would all laugh. The age of moving pictures had arrived! What next? That was 1927.” (Bert and Eva Baker story) “Until 1934 the travelling vaudeville tent show came to Vidora every June, called “Chautauqua”, the big top was pitched, pegs Consul, Saskatchewan pounded and for five days (matinees as well as night), various 306-299-4858 entertainers were on stage—musicals, illusionists, comedy, plays and puppets for the kids. -

THE PRAIRIE FARM REHABILITATION ADMINISTRATION and the COMMUNITY PASTURE PROGRAM, 1937-1947 a Thesis Submitted to the College Of

THE PRAIRIE FARM REHABILITATION ADMINISTRATION AND THE COMMUNITY PASTURE PROGRAM, 1937-1947 A Thesis Submitted to the College ofGraduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements For the Degree ofMaster ofArts In the Department ofHistory University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon By Daniel M Balkwill Spring 2002 ©Copyright Daniel M Balkwill, 2002. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries ofthis University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work has been done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use ofthis thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use ofmaterial in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head ofthe Department ofHistory University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 ii Abstract In 1935, following years of drought, economic depression, and massive relief expenditures, the federal government of Canada passed the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act (PFR Act) to arrest soil drifting, improve cultivation techniques, and conserve moisture on the Canadian prairies. -

St Mary Diversion Dam & Canal Headworks Sherburne Dam & Lake

4 St Mary Canal Halls Coulee Siphon 1 Sherburne Dam & Lake Sherburne 2 St Mary Diversion Dam & Canal Headworks 3 St Mary Canal - River Siphon 5 St Mary Canal Drop Structure The St. Mary Supply System and the greater Milk River Project M Cypress Hills ilk Prov. Park Wa Lethbridge Cypress Hills ters Prov. Park . he k r d e C . e B S A S K A T C H E W A N r r e C C t o a s u i ll r nd v e a er e ry St. Mary Canal detail (U.S.) Riv a B w m y D r r a i lo a k t a g e t F n M Kilometers l e o Eastend . e Cypress r C Eastend 4 t Res. 2 A L B E R T A S C 0 10 20 30 Merryfat Lake CANADA F St. Mary Battle Ravenscrag ren Reservoir Magrath 0 10 20 Creek ek ch UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Cre Oxara m 21 a D Milk Wa M n r Miles Robsart e ter M O N T A N A y n s Middle i h e r n l S d 13 r e C Huff Lake i a a e t d v a Creek Res. v e n . na Ri d i M a l A L B E R T A l dian d 18 C a e r M B C y C ilk n L B R anal Wate a o r y rs u d C r 5 h r g . -

MG 259 - Keith Ewart Photograph Collection

MG 259 - Keith Ewart Photograph Collection Dates: 1885-2009 (inclusive), 1977-2009 (predominant). Extent: ~7000 photographs, 125 glass plates, 322 postcards. Biography: Keith Ewart was born on 9 September 1931, and was raised and schooled in Weyburn, Sk. He trained as a psychiatric nurse and spent most of his working career in Moose Jaw. He has lived in Saskatoon since 1989. A photographer by vocation, in 1975 Ewart began taking images of buildings in Saskatchewan. He has published two volumes of his photographic documentation of railway stations and railway buildings. He passed away in 2011. Scope and content: This collection includes images Keith Ewart has taken of structural landmarks, particularly in Saskatchewan, as well as glass plates from a Moose Jaw photographer ca. 1915-1920. The collection also contains some images that were not taken by Ewart, but were collected by him. Arrangement: This fonds was received inn groups of smaller accessions which have been kept in their original groupings. They are organized as such: Pg. 2001-092: Schools/Churches/Railway Buildings/Moose Jaw portraits. 2 2003-128: Court Houses, Town Halls, Banks, Businesses, Houses. / Bridges, Barns 36 2004-118: Canadian National and Pacific Railway Stations 49 2005-119: Rail stations in British Columbia. Manitoba Alberta 55 2006-112: Ontario, Quebec, Maritimes and USA train stations. 62 2007-100: Rail station photos, various 69 2008-096: Railway station postcards and photos (images by others) 80 2009-103: Elevators photos of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. 87 2010-105: Elevators in Saskatchewan and Alberta. 111 Related collections include the Joanne Abrahamson collection (MG 244); the Hans Dommasch fonds (MG 172); the photographic series in the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool fonds (MG 247); and the Community Progress Competitions in the Walter Murray fonds, (MG 1). -

Boron and Salinity Survey of Irrigation Projects in Saskatchewan

- 242 - BORON AND SALINITY SURVEY OF IRRIGATION PROJECTS IN SASKATCHEWAN W. Nicholaichuk, A.J. Leyshon, Y.W. Jame and C.A. Campbell INTRODUCTION Boron is an essential element for plant growth but the limits between deficiency and toxicity are very narrow. Generally, B toxici ty becomes a problem, in three cases: (1) overfertilization of B-deficient plants with B; (2) in arid soils where B is inherently high; and (3) under irrigation either with B rich waters or where improper irrigation management may result in salt and /or B accumula tion in the root zone. Boron fertilization is not a common practice in Western Canada so problems with the first case have not arisen. With regard to the second and third cases, problems of B toxicity have been overshadowed by the related problem of salinity. As a result, very little atten tion has been paid to B toxicity. Recently, concern has been expressed about the quantities of B that might result from the operation of the Coronach Thermal Power Plant ash lagoons and heat exchanger reservoirs. It is feared that if these are discharged into the Poplar River it may lead ·to undesirable B levels in the irrigation water downstream. The International Poplar River Water Quality Board and Committees of the International Joint Commission apparently encountered diffi culties in trying to establish acceptable concentrations for B and TDS in the Poplar River. They suggested that there was a paucity of data on which to come to a satisfactory conclusion and suggested that little original research on B toxicity had been carried out since Eaton's sand culture work in 1944. -

Fall 2009 Volunteer Power of the World Juniors Page12

University of Saskatchewan | Alumni Magazine | Fall 2009 VOLUNTEER POWER of the World Juniors page12 A Sporting Life The Magic is in the Hard Work The High Speed Pursuit of Olympic Gold An election will be held in the spring of 2010 for seven (7) Senate districts and four (4) member-at-large positions, Nominations that expire on June 30, 2010. Elected Senators serve three- year terms beginning July 1 and are eligible for re-election to a second consecutive term. open for Senators are responsible for making bylaws respecting the discipline of students for any reason other than academic dishonesty; appointing examiners for, and making bylaws respecting, the conduct of examinations for professional societies; providing for the granting of honorary degrees; recommending to the Board and Council proposals received respecting the establishment or disestablishment of any college, University school, department or institute or any affiliation or federation of the University with another educational institution in terms of relevance to the Province; and recommending to the Board or Council any matters or things that the Senate considers necessary to promote the interests of Senate the university. NOMINATIONS FOR and vote for the member of the SASKATCHEWAN DISTRICT Senate to represent the above SENATORS electoral districts. The seven districts in members Saskatchewan that are open for NOMINATIONS FOR nominations are: MEMBERS AT LARGE …your opportunity to participate District 2 There are currently four member Chaplin – Moose Jaw - Rockglen at large positions expiring on June (Postal codes beginning with 30, 2010. Current Senators Richard in university governance S0H, S6K S6J, S6H) Hiebert and Debbie Wagner are eligible for re-election. -

Saskatchewan Official Road

PRINCE ALBERT MELFORT MEADOW LAKE Population MEADOW LAKE PROVINCIAL PARK Population 35,926 Population 40 km 5,992 5,344 Prince Albert Visitor Information Centre Visitor Information 4 3700 - 2nd Avenue West Prince Albert National Park / Waskesieu Nipawin 142 km Northern Lights Palace Meadow Lake Tourist Information Centre Phone: 306-682-0094 La Ronge 88 km Choiceland and Hanson Lake Road Open seasonally 110 Mcleod Avenue W 79 km Hwy 4 and 9th Ave W GREEN LAKE 239 km 55 Phone: 306-752-7200 Phone: 306-236-4447 ve E 49 km Flin Flon t A Chamber of Commerce 6 RCMP 1s 425 km Open year-round 2nd Ave W 3700 - 2nd Avenue West t r S P.O. Phone: 306-764-6222 3 e iv M e R 5th Ave W r e Prince Albert . t Open year-round e l e n c f E v o W ru e t p 95 km r A 7th Ave W t S C S t y S d Airport 3 Km 9th Ave W H a 5 r w 3 Little Red 55 d ? R North Battleford T River Park a Meadow Lake C CANAM o Radio Stations: r HIGHWAY Lions Regional Park 208 km 15th St. N.W. 15th St. N.E. Veteran’s Way B McDonald Ave. C CJNS-Q98-FM e RCMP v 3 Mall r 55 . A e 3 e Meadow Lake h h v RCMP ek t St. t 5 km Northern 5 A Golf Club 8 AN P W Lights H ark . E Airport e e H Ave. -

2013 Report to the IJC.Pdf

Report to THE INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION On THE DIVISION OF THE WATERS OF THE ST. MARY AND MILK RIVERS 2013 Cover Photo: Milk River at Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, Alberta Photograph by Jerry Wagner-Watchel, Environment Canada, Calgary, Alberta REPORT TO THE INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION ON THE DIVISION OF THE WATERS OF THE ST. MARY AND MILK RIVERS FOR THE YEAR 2013 Submitted By Dr. Max M. Ethridge Representing the United States And Dr. Alain Pietroniro Representing Canada April 2014 International Joint Commission Ottawa, Ontario, and Washington, D.C. Commissioners: In compliance with the provisions of Article VI of the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 and Clause VIII(c) of your Order of October 4, 1921, directing the division of the waters of the St. Mary and Milk Rivers between the United States and Canada, we are transmitting herewith a report on the operations during the irrigation season ended October 31, 2013. Respectfully submitted, ________________________________ Dr. Max M. Ethridge Accredited Officer of the United States ________________________________ Dr. Alain Pietroniro Accredited Officer of Her Majesty This page intentionally left blank SYNOPSIS During the 2013 irrigation season, the natural flow of the St. Mary River was 98 percent of the long-term average. The natural flow of the St. Mary River at the International Boundary during the irrigation season, April 1 to October 31, 2013, was 698 400 cubic decametres (dam3) (566,200 acre-feet). Under the terms of the Boundary Waters Treaty, the Canadian allotment was 424 600 dam3 (344,200 acre-feet). The total flow recorded at the International Boundary during the irrigation season was 121 percent of the Canadian allotment.