Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong

Measurement and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong By: Michael Audi, Kathryn Byorkman, Alison Couture, Suzanne Najem ZRH006 Measurement and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Degree of Bachelor of Science In cooperation with Designing Kong Hong, Ltd. and The Harbour Business Forum On March 4, 2010 Submitted by: Submitted to: Michael Audi Paul Zimmerman Kathryn Byorkman Margaret Brooke Alison Couture Dr. Sujata Govada Suzanne Najem Roger Nissim Professor Robert Kinicki Professor Zhikun Hou ii | P a g e Abstract Though Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour is world-renowned, the harbor front districts are far from walkable. The WPI team surveyed 16 waterfront districts, four in-depth, assessing their walkability using a tool created by the research team and conducted preference surveys to understand the perceptions of Hong Kong pedestrians. Because pedestrians value the shortest, safest, least-crowded, and easiest to navigate routes, this study found that confusing routes, unsafe or indirect connections, and a lack of amenities detract from the walkability in Hong Kong. This report provides new data concerning the walkability in harbor front districts and a tool to measure it, along with recommendations for potential improvements. iii | P a g e Acknowledgements Our team would like to thank the many people that helped us over the course of this project. First, we would like to thank our sponsors Paul Zimmerman, Dr. Sujata Govada, Margaret Brooke, and Roger Nissim for their help and dedication throughout our project and for providing all of the resources and contacts that we required. -

Hong Kong's Pro-Democracy Protests

Protests & Democracy: Hong Kong’s Pro-Democracy Protests Jennifer Yi Advisor: Professor Tsung Chi Politics Senior Comprehensive Project Candidate for Honors consideration April 10, 2015 2 Abstract Protests that occur in the public sphere shed light on the different types of democracy that exist in a region. A protester’s reason for participation demonstrates what type of democracy is missing, while a protest itself demonstrates what type of democracy exists in the region. This Politics Senior Comprehensive Project hypothesizes that the recent pro-democracy protests in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (“Hong Kong”), dubbed the Umbrella Movement, demonstrate an effective democracy due to active citizen engagement within the public sphere. Data is collected through personal interviews of Umbrella Movement participants that demonstrate what type of democracy currently exists in Hong Kong, what type of democracy protesters are looking for, and what type of democracy exists as a result of the recent protests. The interviews show that a true representative and substantive democracy do not exist in Hong Kong as citizens are not provided the democratic rights that define these types of democracy. However, the Umbrella Movement demonstrates an effective democracy in the region as citizens actively engage with one another within the public sphere for the purpose of achieving a representative and substantive democracy in Hong Kong. 3 I. Introduction After spending most of my junior year studying in Hong Kong, I have become very interested in the region and its politics. I am specifically interested in the different types of democracy that exist in Hong Kong as it is a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China (“China”). -

Dental Care Services for Older Adults in Hong Kong—A Shared Funding, Administration, and Provision Mode

healthcare Review Dental Care Services for Older Adults in Hong Kong—A Shared Funding, Administration, and Provision Mode Stella Xinchen Yang , Katherine Chiu Man Leung, Chloe Meng Jiang and Edward Chin Man Lo * Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] (S.X.Y.); [email protected] (K.C.M.L.); [email protected] (C.M.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-852-2859-0292 Abstract: Hong Kong has a large and growing population of older adults but their oral health conditions and utilization of dental services are far from optimal. To reduce the financial barriers and to improve the accessibility of dental care services to the older adults, a number of programmes adopting an innovative shared funding, administration, and provision mode have recently been implemented. In this review, an online search on the Hong Kong government websites and the electronic medical literature databases was conducted using keywords such as “dental care,” “dental service,” and “Hong Kong.” Dental care services for older adults in Hong Kong were identified. These programmes include government-funded outreach dental care service provided by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), provision of dentures and related treatments by private and NGO dentists supported by the Community Care Fund, and government healthcare vouchers for private healthcare, including dental, services. This paper presents the details of the operation of these programmes and the initial findings. There is indirect evidence that these public-funded dental care service programmes have gained acceptance and support from the government, the service recipients, and Citation: Yang, S.X.; Leung, K.C.M.; the providers. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 18

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 18 November 2010 2357 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 18 November 2010 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. 2358 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 18 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. THE HONOURABLE LEE WING-TAT DR THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. -

Empowering Parents' Choice of Schools

Volume 14, Number 1 ISSN 1099-839X Empowering Parents’ Choice of Schools: The Rhetoric and Reality of How Hong Kong Kindergarten Parents Choose Schools Under the Voucher Scheme FUNG, Kit-Ho Chanel The Chinese University of Hong Kong And LAM, Chi-Chung The Hong Kong Institute of Education Citation Fung, K. & Lam, C. (2011). Empowering Parents’ Choice of Schools: The Rhetoric and Reality of How Hong Kong Kindergarten Parents Choose Schools Under the Voucher Scheme. Current Issues in Education, 14(1). Retrieved from http://cie.asu.edu/ Abstract School choice gives parents greater power over their children’s education. But ever since the Pre-primary Education Voucher Scheme (PEVS) was introduced in Hong Kong in 2007, school choice has become a hotly debated topic. The scheme was introduced to empower kindergarten parents in choosing a school for their children by offering them direct fee subsidies that, in return, could propel education quality forward. Parents in the private kindergarten sector, however, have long enjoyed the privilege of choice, and they have been preoccupied with an intense interest in their children’s academic upbringing, even if it means compromising the holistic development of their children. This runs counter to the principles of a quality education. Therefore, the urge to further promote parental kindergarten choice will likely allow parental academic interests to continue to prevail and hence invalidate the PEVS’ promise to improve Current Issues in Education Vol. 14 No. 1 2 education quality. The result is a unique dilemma between school choice for parents and the promise of education quality within Hong Kong’s unique private kindergarten sector. -

Parent-Teacher Association Handbook

Parent-Teacher Association Handbook Committee on Home-School Co-operation Preface 3 CHAPTER ONE: INAUGURATION 1.1 Aims and Functions of a Parent-Teacher Association 5 1.2 Preparation 5 1.3 Executive Committee Members of the Parent-Teacher Association and 6-8 a Summary of their duties 1.4 Types of Registration for Parent-Teacher Associations 8-12 1.5 Constitution 12 1.6 The First General Meeting of Parents 13 1.7 Points to Note during Elections and Voting 13 CHAPTER TWO: OPERATION 2.1 Preparation of an Annual Plan 15 2.2 Suggested Activities 15 2.3 Meetings of the Parent-Teacher Association 15-18 CHAPTER THREE: INSURANCE 3.1 Procurement of School Insurance 20 3.2 Block Insurance Policy 20 3.3 Protection for Activities of the Parent-Teacher Association 21 CHAPTER FOUR: FINANCE 4.1 Sources of Income 23 4.2 Home-School Co-operation Grants 23-25 4.3 Financial Management 25-27 4.4 Duties of the Executive Committee 27 4.5 Duties of the Treasurer 27 4.6 Drawing up a Budget 27 4.7 Handling Income and Expenditure 27-29 4.8 Financial Report 29-30 CHAPTER FIVE: PARENT MANAGERS 5.1 School-Based Management Governance Framework 32 5.2 Recognized Parent-Teacher Association 32 5.3 Parent Managers 32 5.4 Alternate Parent Manager 32-33 5.5 Nomination, Election and Vacation of Office of Parent Managers 33-34 CHAPTER SIX: NETWORKING 6.1 Home-School Networking 36-37 6.2 District-Based Networking 37-38 6.3 Proper Use of Community Resources 38 APPENDICES (1) – (10) 40-67 2 Parent-Teacher Association Handbook Preface The “Committee on Home-School Co-operation (CHSC)” was established in 1993. -

Multi-Hazard Risk Assessment of Two Hong Kong Districts

Research Papers Issue RP0273 Multi-hazard risk assessment of two December 2015 Hong Kong districts Division: Economic analisys of Climate Impacts and Policy (ECIP) By Katie Johnson SUMMARY The assessment of multi-hazard risks in urban areas poses CMCC/ECIP [email protected] particular difficulties due to the different temporal and spatial scales of hazardous events in urban contexts, and the potential interactions between Yaella Depietri Urban Ecology single hazards and between hazards and different socio-economic Lab,Environmental Studies fragilities. Yet this exercise is important, as identifying the spatial distribution Program,The New School,New and concentration of risks in urban areas helps determine where and how York [email protected] preventive and corrective actions can reduce levels of vulnerability and exposure of urban populations. This article presents the results of a and Margaretha Breil CMCC/ECIP GIS-based assessment of present day risks to socio-natural hazards in two [email protected] districts of Hong Kong (PRC) by utilizing indicators to describe the hazards and vulnerabilities. Mapping composite indicators facilitates the communication of complex concepts like vulnerability and multi-hazard risk, allowing for the visual representation of concentrations of hazard intensities and vulnerabilities. Mapping indicators operationalizes the concept of vulnerability at the urban level, and supports the detection of potentially risk prone areas at the sub-urban scale. This approach has the potential of providing city planners and policy makers with visual guidance in focusing The research leading to and prioritizing risk management and adaptation actions with respect to these results has received funding from the current and future risks existing in specific parts of the city, taking into Italian Ministry of account more than one hazard at the time. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EVERYDAY IMAGININGS UNDER the LION ROCK: an ANALYSIS of IDENTITY FORMATION in HONG KONG a Di

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EVERYDAY IMAGININGS UNDER THE LION ROCK: AN ANALYSIS OF IDENTITY FORMATION IN HONG KONG A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICS by Sarah Y.T. Mak March 2013 The Dissertation of Sarah Y.T. Mak is approved: _______________________________ Professor Megan Thomas, Chair ________________________________ Professor Ben Read ________________________________ Professor Michael Urban ________________________________ Professor Lisa Rofel ______________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Sarah Y.T. Mak 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ...............................................................................................................................vi Acknowledgments.........................................................................................................viii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................1 I. SETTING THE SCENE .......................................................................................................1 II. THE HONG KONG CASE ............................................................................................. 15 III. THEORETICAL STARTING POINTS ........................................................................... -

Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance Committee Members in Examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2020-21 Home

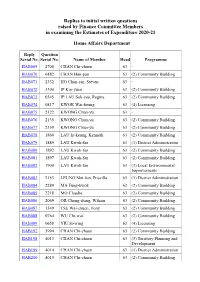

Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2020-21 Home Affairs Department Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme HAB069 2700 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 - HAB070 0482 CHAN Han-pan 63 (2) Community Building HAB071 2332 HO Chun-yin, Steven 63 - HAB072 3300 IP Kin-yuen 63 (2) Community Building HAB073 0345 IP LAU Suk-yee, Regina 63 (2) Community Building HAB074 0817 KWOK Wai-keung 63 (4) Licensing HAB075 2122 KWONG Chun-yu 63 - HAB076 2135 KWONG Chun-yu 63 (2) Community Building HAB077 2359 KWONG Chun-yu 63 (2) Community Building HAB078 1860 LAU Ip-keung, Kenneth 63 (2) Community Building HAB079 1889 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (1) District Administration HAB080 1892 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (2) Community Building HAB081 1897 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (2) Community Building HAB082 1900 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (3) Local Environmental Improvements HAB083 2153 LEUNG Mei-fun, Priscilla 63 (1) District Administration HAB084 2289 MA Fung-kwok 63 (2) Community Building HAB085 2218 MO Claudia 63 (2) Community Building HAB086 2049 OR Chong-shing, Wilson 63 (2) Community Building HAB087 1349 TSE Wai-chuen, Tony 63 (2) Community Building HAB088 0764 WU Chi-wai 63 (2) Community Building HAB089 0658 YIU Si-wing 63 (4) Licensing HAB197 3994 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (2) Community Building HAB198 4013 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (5) Territory Planning and Development HAB199 4014 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (1) District Administration HAB200 4015 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (2) Community Building Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. -

Download PDF File Format Form

Quality Services for Quality Life Annual Report 2018-2019 Contents Pages 1. Foreword 1-4 2. Performance Pledges 5-6 3. Vision, Mission & Values 7-8 4. Leisure Services 9-56 Leisure Services 9 Recreational and Sports Facilities 10-28 Recreational and Sports Programmes 29-35 Sports Subvention Scheme 36-38 2018 Asian Games and Asian Para Games in Indonesia 39-40 The 7th Hong Kong Games 41-42 Sports Exchange and Co-operation Programmes 43 Horticulture and Amenities 44-46 Green Promotion 47-52 Licensing 53 Major Recreational and Sports Events 54-56 5. Cultural Services 57-165 Cultural Services 57 Performing Arts 58-62 Cultural Presentations 63-69 Contents Pages Festivals 70-73 Arts Education and Audience-Building Programmes 74-80 Carnivals and Entertainment Programmes 81-84 Cultural Exchanges 85-91 Film Archive and Film and Media Arts Programmes 92-97 Music Office 98-99 Indoor Stadia 100-103 Urban Ticketing System (URBTIX) 104 Public Libraries 105-115 Museums 116-150 Conservation Office 151-152 Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO) 153-154 Major Cultural Events 155-165 6. Administration 166-193 Financial Management 166-167 Human Resources 168-180 Information Technology 181-183 Facilities and Projects 184-185 Outsourcing 186-187 Environmental Efforts 188-190 Public Relations and Publicity 191-192 Public Feedback 193 7. Appendices 194-218 Foreword The LCSD has another fruitful year delivering quality leisure and cultural facilities and events for the people of Hong Kong. In its 2018-19 budget, the Government announced that it would allocate $20 billion to improve cultural facilities in Hong Kong, including the construction of the New Territories East Cultural Centre, the expansion of the Hong Kong Science Museum and the Hong Kong Museum of History, as well as the renovation of Hong Kong City Hall. -

A Territory Wide Survey on Indoor Particulate Level in Hong Kong

AIVC 11693 PERGAMON Building and Environment 34 (1999) 213-220 A territory wide survey on indoor particulate level in Hong Kong Thomas C. W. Tunga·*, Christopher Y. H. Chaob, John Burnetta, S. W. Pant, Raymond Y. M. Leec "Departmenr of Building Serrices Engineering The Hong Kong Polytechnic Unit-ersity, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kang b Depar1men1 of lv/echanicalEngineering The Hong Kong Unirersity of Science and Technology 'The Hong Kong Enrironmental Protection Deparrment Abstract Airborne particulates are a major air pollution problem in Hong Kong. Very high outdoor airborne particulate levels have been recorded in the outdoor monitoring stations managed by the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department (HKEPD). However, information on the concentrations of indoor total suspended particulate (TSP) and particulate matters of aerodynamic size less than I 0 µm {PM 10) ha been scarce. In view of this. a territory-wide survey was conducted from September 1996 to January 1997 to investigate the indoor airborne particulate levels in SO residential apartments in Hong Kong. In this study, 50 residential premises were selected in 18 districts of Hong Kong covering both public housing and private housing. Two Mini-Vol sampling pumps were located al each site to collect both 24 h TSP ilnd PM 10 samples in filters which were analyzed by gravimetric method using a precision mas balance. The living habit . ventilation characteristics and other indoor activities were recorded in a survey form. The TSP level varied from 37.5 pg m-3 to 227.1 11g m-3 and the PMio level varied from 35. l µg m-3 to 161.6 µg m-3, which were much higher than the levels measured in western countries. -

Review on the Role, Functions and Composition of District Councils

CONTENTS Contents Page Chapter One : Introduction 1 Chapter Two : Management of District Facilities 7 Chapter Three : Capital Works Improvement to 15 District Facilities and District Minor Works Chapter Four : Strengthening the Role of District Officers and 19 Enhancing Communication with District Councils Chapter Five : Enhancing District Partnership 24 Chapter Six : Support for District Councils Members 27 Chapter Seven : Composition of District Councils 32 Chapter Eight : District Council Election-related Matters 39 Chapter Nine : Financial and Staffing Implications 44 Chapter Ten : Concluding Remarks : Views Sought 46 Appendix 50 Chapter One Introduction District Administration Scheme 1.1 In 1980, the Government published a Green Paper entitled ‘A Pattern of District Administration in Hong Kong’ and invited public views on the proposed District Administration Scheme. Following consultation, the District Administration Scheme was introduced in 1982 with the following objectives – (a) to achieve a more effective coordination of government activities in the provision of services and facilities at the district level; (b) to ensure that Government is responsive to district needs and problems; and (c) to promote public participation in district affairs. 1.2 Under the Scheme, District Boards (DBs) (renamed “District Councils” (DCs) in 2000) were set up in the 18 districts of Hong Kong. There were also 18 District Management Committees, chaired by District Officers, set up to coordinate the efforts of government departments in districts. Since their establishment in 1982, DCs have been playing an essential advisory role on district matters and territory-wide issues. Apart from reflecting public opinion and promoting community building, they have been playing an instrumental role in monitoring the delivery of public services at district level and promoting government initiatives.