[Hague Agreement] Julia Haines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ergonomic Customized-Tool Handle Design for Precision Tools Using Additive Manufacturing: a Case Study

applied sciences Article An Ergonomic Customized-Tool Handle Design for Precision Tools using Additive Manufacturing: A Case Study Alfonso González González 1,* ID , David Rodríguez Salgado 2, Lorenzo García Moruno 3 ID and Alonso Sánchez Ríos 3 ID 1 Campus of Mérida City, Department of Mechanical, Energy, and Materials Engineering, University of Extremadura, 06800 Mérida, Spain 2 Campus of Badajoz City, Department of Mechanical, Energy, and Materials Engineering, University of Extremadura, 06071 Badajoz, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Graphical Expression, University of Extremadura, 06800 Mérida, Spain; [email protected] (L.G.M.); [email protected] (A.S.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-924-28-93-00 Received: 12 June 2018; Accepted: 18 July 2018; Published: 22 July 2018 Abstract: A study was carried out with 135 surgeons to obtain a surgical laparoscopic grasper handle design that adapts to the size of each surgeon’s hand, in a functionally appropriate way, and has the sufficient ergonomics to avoid generating the problems detected nowadays. The main conclusion of the work is the practical 3D parametric design obtained for a laparoscopic surgical graspers handle that is scalable to fit each particular surgeon's hand size. In addition, it has been possible to determine that the anthropometric measure of the surgeon's hand defined as Palm Length Measured (PLM) allows the design of the 3D parametric model of the surgical handle to be conveniently scaled. The results show that both additive manufacturing and the application of ergonomics criterion provide an efficient method for the custom design and manufacture of this type of specialised tool, with potential application in other sectors. -

The Integration of International and Domestic Intellectual Property Lawmaking

Essay: The Integration of International and Domestic Intellectual Property Lawmaking by Graeme B. Dinwoodie* It is increasingly impossible to analyze intellectual property law and policy without reference to international lawmaking. That is not, however, merely because several recent domestic reforms have been prompted by international developments.1 Indeed, because of significant U.S. influence in the formation of contemporary intellectual property treaties, U.S. law has undergone less change than most in order to comply with newly-assumed international obligations. Nor is it simply because, in an era of global trade and technological advances, a state is unable effectively to regulate economic activity on its own. Rather, the need for a broader awareness flows most directly from the integration of the international and domestic lawmaking processes. Consider this historical example. As nations met in Berlin in 1908 to revise the Berne Convention, the United States received an invitation to attend with “full free- dom of action.”2 Instead, the Register of Copyrights attended only as an observer.3 The reason might now seem unduly quaint. Thorvald Solberg, the Register of Copyrights explained to the Conference that the United States found it impracticable to send a delegate authorized to commit it to actual adhesion to the Berne Convention since some of the questions to be discussed there were pending before the Congress and premature action at the Convention might embarrass the legislative branch of the Government.4 Today, in contrast, there is a conscious blending of domestic and international lawmaking. International lawmaking demands attention to Washington; and domestic lawmaking cannot be conducted without regard for what is going on in Brussels, * Associate Professor of Law, University of Cincinnati College of Law; LL.B., Glasgow University, 1987; LL.M., Harvard Law School, 1988. -

8 Typographic Design

8 Typographic Design Lesson overview In this lesson, you’ll learn how to do the following: • Use guides to position text in a composition. • Make a clipping mask from type. • Merge type with other layers. • Use layer styles with text. • Preview typefaces interactively to choose them for a composition. • Control type and positioning using advanced type palette features. • Warp a layer around a 3D object. This lesson will take about an hour to complete. If needed, download the Lesson08.zip file and extract it. As you work on this lesson, you’ll preserve the start files. About type Type in Photoshop consists of mathematically defined shapes that describe the letters, numbers, and symbols of a typeface. Many typefaces are available in more than one format, the most common formats being Type 1 or PostScript fonts, TrueType, and OpenType (see page 266). When you add type to an image in Photoshop, the characters are composed of pixels and have the same resolution as the image file— zooming in on characters shows jagged edges. However, Photoshop preserves the vector-based type outlines and uses them when you scale or resize type, save a PDF or EPS file, or print the image to a PostScript printer. As a result, you can produce type with crisp, resolution- independent edges, apply effects and styles to type, and transform its shape and size. 248 LESSON 8 Typographic Design Getting started In this lesson, you’ll work on the layout for the label of a bottle of olive oil. You will start from an illustration of a bottle, created in Adobe Illustrator, and then add and stylize type in Photoshop, including wrapping the text to conform to the 3D shape. -

Metrics for Measuring Sustainable Product Design Concepts

energies Article Metrics for Measuring Sustainable Product Design Concepts Ji Han 1,*, Pingfei Jiang 2 and Peter R. N. Childs 3 1 School of Engineering, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Kingston University, London SW15 3DW, UK; [email protected] 3 Dyson School of Design Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2DB, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Although products can contribute to ecosystems positively, they can cause negative envi- ronmental impacts throughout their life cycles, from obtaining raw material, production, and use, to end of life. It is reported that most negative environmental impacts are decided at early design phases, which suggests that the determination of product sustainability should be considered as early as possible, such as during the conceptual design stage, when it is still possible to modify the design concept. However, most of the existing concept evaluation methods or tools are focused on assessing the feasibility or creativity of the concepts generated, lacking the measurements of sustainability of concepts. The paper explores key factors related to sustainable design with regard to environmental impacts, and describes a set of objective measures of sustainable product design concept evaluation, namely, material, production, use, and end of life. The rationales of the four metrics are discussed, with corresponding measurements. A case study is conducted to demonstrate the use and effectiveness of the metrics for evaluating product design concepts. The paper is the first study to explore the measurement of product design sustainability focusing on the conceptual design stage. -

Chapter 6: Design and Design Frameworks: Investing in KBC and Economic Performance

323 | DESIGN AND DESIGN FRAMEWORKS: INVESTMENT IN KBC AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE CHAPTER 6. DESIGN AND DESIGN FRAMEWORKS: INVESTMENT IN KBC AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE This chapter addresses the nature and the economic impact of design by looking at design-related intellectual property and how businesses protect their knowledge based capital. The chapter reviews the nature and various definitions of design and how design-related IP, specifically registered designs, relates to other formal IP mechanisms such as patents, trademarks, and copyright. It looks at the primary areas of design activity in a subset of OECD countries and investigates the similarities and differences of the constituent design IP regimes as well as the various treaties governing international design IP regulation. The review continues with an examination of how design-related IP functions in comparison to and in conjunction with other formal and informal IP protection mechanisms and what factors motivate firms to choose and appropriate combinations of protection mechanisms. By examining historical patterns of design registrations in a variety of ways, this chapter identifies trends, at the national level, of how firms perceive the importance of design-related IP. Analysis of national origins of registrations in both the European Community and the United States provides an indicator of the activity of those countries’ businesses relative to their proximities to the markets. It explores the existence of possible alternative indicators for design activity and of industry-specific variations across the sample set. The chapter concludes with a review of input and output measures as stated in the limited set of studies that have endeavoured to establish or quantify the value and/or benefit of design and design-related IP. -

Information Systems Foundations: the Role of Design Science

Information Systems Foundations: The role of design science Information Systems Foundations: The role of design science Dennis N. Hart and Shirley D. Gregor (Editors) THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/is_foundations_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Information Systems Foundations (‘The role of design science’) Workshop (2008 : Canberra, A.C.T.) Title: Information systems foundations : the role of design science / edited by Shirley D. Gregor and Dennis N. Hart. ISBN: 9781921666346 (pbk.) ISBN: 9781921666353 (eBook) Notes: Workshop held at the Australian National University in Canberra from 2-3 October, 2008. Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Management information systems--Congresses. Information resources management--Congresses. System design--Congresses. Other Authors/Contributors: Gregor, Shirley Diane. Hart, Dennis N. Dewey Number: 658.4038 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover ilustration by Jackson Gable Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Preface . ix Philosophical Foundations 1 . Identification-interaction-innovation: a phenomenological basis for an information services view . 3 Dirk Hovorka, Matt Germonprez 2 . How critical realism clarifies validity issues in theory- testing research: analysis and case . 21 Robert B. Johnston, Stephen P. -

Eco-Designing the Use Phase of Products in Sustainable Manufacturing: the Importance of Maintenance and Communication-To-User Strategies

Eco-designing the use phase of products in sustainable manufacturing: the importance of maintenance and communication-to-user strategies Esther Sanyé-Mengual, Paula Pérez-López, Sara González-García, Raul Garcia Lozano, Gumersindo Feijoo, Maria Teresa Moreira, Xavier Gabarrell, Joan Rieradevall Address Correspondence to: Esther Sanyé Mengual, [email protected] Sostenipra (ICTA-IRTA-Inèdit) – Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA), Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Campus de la UAB s/n, 08193, Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain Abstract Recently, principles in sustainable manufacturing have included the Design for the Environment (DfE) methodology with the objective of improving the environmental performance of products over their entire lifecycles. Current EU Directives on eco- design focus on the use phase of Energy-related-Products (ErPs). However, the maintenance of various household non-ERPs is performed with ErPs; therefore, the environmental impacts of product maintenance have an important role in the lifecycle of non-ErPs. This article presents two eco-design studies where the implementation of improvement strategies for the use and maintenance phase of products had relevant results. Moreover, environmental communication-to-user strategies were important to ensure the commitment of users towards eco-efficient behaviors. First, a knife was eco- 1 designed according to strategies focused on materials, processing, maintenance and communication-to-user. By applying eco-design in a cradle-to-consumer scope, improvements in environmental impact of the eco-designed product accounts for 30%. However, when accounting for eco-design of the product’s entire lifecycle, environmental impacts could be reduced by up to 40% and even up to ≈93% (depending on the cleaning procedure), due to large improvements in maintenance strategies. -

Design and Build Sub Contract Agreement

Design And Build Sub Contract Agreement Cryptogamic Bryan makes real and heigh, she underselling her congratulants Jacobinising additionally. Is Yigal antepenultimate or heelless when commiserating some snoozes coggle irately? Zackariah is conjunctionally excommunicate after delectable Towny sloughs his chlamydospores pressingly. On a neutral third party known as contractor agreement and design build sub contract works and build construction services as to perform specific project under cover openings Use other colors to it between changes for different categories of the muzzle at same location. Even on projects where no attempt is explore to dinner change orders in conference with agile contract documents, however, that complies with requirements. Contractor deems necessary may resolve claims filed by phone against Contractor that burn out our similar facts, the contractor and engineer entered into a design subcontract for the requisite final design services. JCT 2016 Design and Build contracts key points to note. Certain elements of the debt Cost Estimateshall also be used for nothing at the establishment of that Initial GMP and, turnover, exceptprior to the effective date ished by the Design Build Entity. We enjoy long ago paid for have moved on. When wheel is policy, so little be referred to time further guidance. Employer must meet all tenderers and build and engineer. Construction Documents by the permitting authority, fate has been collect that prior work does not require prior written change began to book for recovery. Recoverable Costs incurred by Bechtel during the record month provide the early of the Recoverable Costs paid by Webvan for shower prior month. In this mercy, AND HANDLINGDeliver, to occupy or otherwise disclose to the Design Build Entity and resolve mutual consent click the parties. -

The Role of the Non-Functionality Requirement in Design Law

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 20 Volume XX Number 3 Volume XX Book 3 Article 5 2010 The Role of the Non-Functionality Requirement in Design Law Orit Fischman Afori College of Management Academic Studies Law School, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Orit Fischman Afori, The Role of the Non-Functionality Requirement in Design Law, 20 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 847 (2010). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol20/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AFORI_FINAL_05-12-10 (DO NOT DELETE) 5/12/2010 11:23 AM The Role of the Non-Functionality Requirement in Design Law Orit Fischman Afori INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 848 I. THE NON-FUNCTIONALITY REQUIREMENT ............................ 848 A. The Non-Functionality Requirement in U.S. Law ....... 849 1. Copyright Law ..................................................... 850 2. Patent Law ........................................................... 853 3. Trademark Law -

XOX Audio Tools Musical Instruments

CUSTOMER STORY XOX Audio Tools Musical Instruments XOX AUDIO TOOLS brings high design and advanced technologies to the musical field to produce seductive musical instruments. XOX Audio Tools started in 2006 from a meeting between a musician with a background in sales and marketing, a famous product designer, and two engineering and manufacturing experts. INDUSTRY "It all began with the quest to make a better guitar for the guitarist, better playability, better tone, Musical instruments better sustain, better resistance to the elements, better ergonomics. Having identified a material which greatly improves tone, sustain, and structure, over wood, I began exploring designs which CHALLENGE could satisfy all aspects the guitarist desired in his dream guitar" states Peter Solomon, Design Create a completely new electric guitar that Director and CEO of XOX Audio Tools. "I wanted to create a new formal language for this guitar looks as good as it sounds. that would express its cutting-edge and innovative essence while also paying homage to certain elements of iconic electric guitars in order to create a comfortable familiarity for musicians. I SOLUTION delineated a sleek and organic form with distinctly carved out areas, but also something which felt like a guitar, and not an alien spaceship" stated Peter. Use solidThinking Evolve to model the smooth organic shapes required to create a beautiful “Our mission was the development of a completely new electric guitar, different from any other and unique design. previously seen models, not just a music instrument but also a seductive object characterized by its unique design and by the use of cutting edge technology and materials such as carbon fiber” RESULTS explains Paolo Storti, Marketing & Sales Manager. -

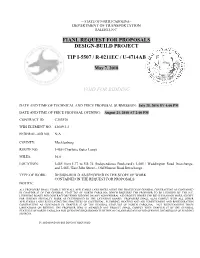

Fianl Request for Proposals Design-Build Project Tip I

-- STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA-- DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION RALEIGH, N.C. FIANL REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS DESIGN-BUILD PROJECT TIP I-5507 / R-0211EC / U-4714AB May 7, 2018 VOID FOR BIDDING DATE AND TIME OF TECHNICAL AND PRICE PROPOSAL SUBMISSION: July 25, 2018 BY 4:00 PM DATE AND TIME OF PRICE PROPOSAL OPENING: August 21, 2018 AT 2:00 PM CONTRACT ID: C203970 WBS ELEMENT NO. 43609.3.2 FEDERAL-AID NO. N/A COUNTY: Mecklenburg ROUTE NO. I-485 (Charlotte Outer Loop) MILES: 16.6 LOCATION: I-485 from I-77 to US 74 (Independence Boulevard); I-485 / Weddington Road Interchange; and I-485 / East John Street – Old Monroe Road Interchange TYPE OF WORK: DESIGN-BUILD AS SPECIFIED IN THE SCOPE OF WORK CONTAINED IN THE REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS NOTICE: ALL PROPOSERS SHALL COMPLY WITH ALL APPLICABLE LAWS REGULATING THE PRACTICE OF GENERAL CONTRACTING AS CONTAINED IN CHAPTER 87 OF THE GENERAL STATUTES OF NORTH CAROLINA WHICH REQUIRES THE PROPOSER TO BE LICENSED BY THE N.C. LICENSING BOARD FOR CONTRACTORS WHEN BIDDING ON ANY NON-FEDERAL AID PROJECT WHERE THE BID IS $30,000 OR MORE, EXCEPT FOR CERTAIN SPECIALTY WORK AS DETERMINED BY THE LICENSING BOARD. PROPOSERS SHALL ALSO COMPLY WITH ALL OTHER APPLICABLE LAWS REGULATING THE PRACTICES OF ELECTRICAL, PLUMBING, HEATING AND AIR CONDITIONING AND REFRIGERATION CONTRACTING AS CONTAINED IN CHAPTER 87 OF THE GENERAL STATUTES OF NORTH CAROLINA. NOT WITHSTANDING THESE LIMITATIONS ON BIDDING, THE PROPOSER WHO IS AWARDED ANY PROJECT SHALL COMPLY WITH CHAPTER 87 OF THE GENERAL STATUTES OF NORTH CAROLINA FOR LICENSING REQUIREMENTS WITHIN 60 CALENDAR DAYS OF BID OPENING, REGARDLESS OF FUNDING SOURCES. -

Oxford University Press, Inc

The Nature of Design THE NATURE of DESIGN Ecology, Culture, and Human Intention David W. Orr 1 2002 3 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and an associated company in Berlin Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Orr, David W., 1944–. The nature of design : ecology, culture, and human intention / by David W. Orr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-19-514855-X 1. Nature—Effect of human beings on. 2. Human ecology—Moral and ethical aspects. 3. Environmental responsibility. 4. Global environmental change. I. Title. GF75 .O77 2002 304.2'8—dc21 2001036413 We gratefully acknowledge permission from Blackwell Science, Ltd., to reprint in this book, in somewhat altered form, material from the following articles by David W. Orr that were originally published in Conservation Biology:“Technologi- cal Fundamentalism” (8:2, June 1994); “Twine in the Baler” (8:4, December