Water Governance in Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

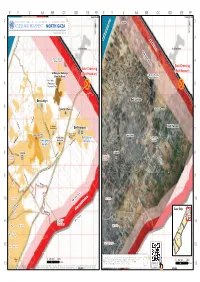

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

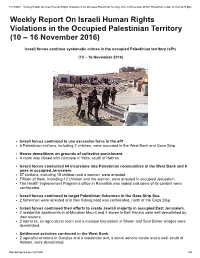

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights

11/17/2016 Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continue systematic crimes in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continued to use excessive force in the oPt 6 Palestinian civilians, including 2 children, were wounded in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. House demolitions on grounds of collective punishment. A room was closed with concrete in Yatta, south of Hebron. Israeli forces conducted 64 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank and 6 ones in occupied Jerusalem. 57 civilians, including 15 children and a woman, were arrested. Fifteen of them, including 12 children and the woman, were arrested in occupied Jerusalem. The Health Improvement Program’s office in Ramallah was raided and some of its content were confiscated. Israeli forces continued to target Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Strip Sea. 2 fishermen were arrested and their fishing boat was confiscated, north of the Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued their efforts to create Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem. 2 residential apartments in alMukaber Mount and 2 stores in Beit Hanina were selfdemolished by their owners. 2 barracks, an agricultural room and a mosque foundation in Silwan and Sour Baher villages were demolished. Settlement activities continued in the West Bank. 2 agricultural rooms in Qalqilya and a residential tent, a social service centre and a well, south of Hebron, were demolished. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

Security Council Ic

UNITED NATIONS Security Council Distr. Ic GENERAL s/14930 26 March 1982 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH LETTER DATED 25 MARCH 1982 FROM THE PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF JORDAN TO THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL I have the honour to forward to you the enclosed letter, at the request of Mr. zuhdi Labib Terzi, the Permanent Cbserver of the Palestine Liberation Organization, concerning further acts of brutality against the Mayor of Nablus, Mr. Bassam Shakaa and the Mayor of Ramallah, Mr. Kaeim Khalef, who were arrested and removed from their legally elected offices. Inasmuch as these acts of terror and brutality continue to pervade the occupied Palestinian territory, I would deeply appreciate it if my letter and the enclosed letter from the Permanent Observer of the Palestine Liberation Organization could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Hazem NUSEIBEH Ambassador Permanent Representative 82-07682 0300~ (E) / ,.. s/14930 hglish Annex Page 1 ---Annex Ix'cter dated 25 March 1982 from the Permanent Observer of the' Palestine Liberation Organization to the Uhited Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council I am requested by Chairman Yasser Arafat to bring the following to your most urgent attention. ?bday Mayor Bassam Shakaa of Nablus and Mayor Karim Khalef of Ramallah were arrested and removed from their legally elected offices. Israeli troops then installed so-called civilian administrators in their place. Speculation is 'chat the arrests of Shakaa and Khalef precede their forceable deportation and exile from Palestine. Members of the Nablus municipality and a number of Shakaa's supporters were summoned to General Menahem Milson's office and threatened with severe repercussions should they allow the situation in Nablus to deteriorate. -

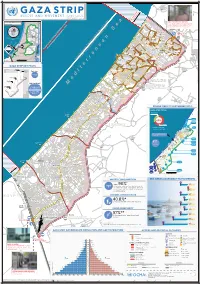

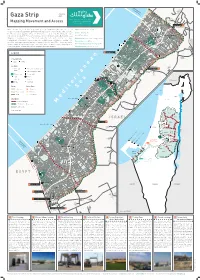

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

Palestinian Security Sector Governance

Palestinian Security Sector Governance Challenges and Prospects Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, Jerusalem (PASSIA) Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) August 2006 Copyright © PASSIA – DCAF, 2006 P.O. Box 19545, Jerusalem Tel.: (02)626 4426 Fax: (02)628 2819 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.passia.org P.O. Box 1360, CH-1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland Tel.: +41 (22) 741 77 00 Fax: +41 (22) 741 77 05 Website: www.dcaf.ch The Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA) is an independent Palestinian non-profit institution, not affiliated with any government, political party or organization. PASSIA seeks to present the Palestine Question in its national, regional and international contexts through academic research, dialogue and publication. PASSIA endeavours that research undertaken under its auspices be specialized and scientific and that its symposia and workshops, whether international or intra-Palestinian, be open, self- critical and conducted in a spirit of cooperation. The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) promotes good governance and reform of the security sector. The Centre conducts research on good practices, encourages the development of appropriate norms at the national and international levels, makes policy recommendations and provides in-country advice and assistance programmes. DCAF’s partners include governments, parliaments, civil society, and international organizations. Disclaimer The views presented in this book are personal, i.e., that of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of PASSIA or DCAF. The publication of this book was kindly supported by the Geneva Centre for Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF). -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I T E D OCHA N A WeeklyT I O NRepor S t: 31 January – 6 February 2007 N A T I O N S U N| 1 I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org P r o t e c t i o n o f C i v i l i a n s W e e k l y R e p o r t 31 January – 6 February 2007 Of note this week Gaza Strip: A number of incidents occurred between Israeli forces and Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, but the ceasefire held. Internal violence: − Inter-factional fighting continued in the Gaza Strip. According to MoH sources, 34 Palestinians died, including two women and four children, and 251 were injured.1 − Five Palestinians, including a woman bystander, were killed and 24 others injured when Hamas ESF ambushed trucks carrying containers that belonged to the Presidential Guard. − The Presidential Guard broke into the Islamic University and clashed with the Hamas ESF. Significant damages to the university’s buildings including the main library were reported. − Schooling in the Gaza Strip was severely disturbed, more significantly in Gaza City and northern Gaza. − Checkpoints and presence of snipers severely affected civilian life in the Gaza Strip. West Bank: − Six Palestinians were killed and 16 injured in the West Bank. One IDF soldier was injured. − 131 ‘flying’ or random checkpoints set up by the IDF were observed; 135 search and arrest operations were conducted by the IDF resulting in 145 arrests predominately in Hebron, Jenin and Nablus governorates. -

Monthly Violations Report September 2020 the Israeli Systematic Attacks

Monthly Violations Report September 2020 The Israeli systematic attacks on the Palestinian agricultural sector in the West Bank and Gaza Strip UAWC’s Agricultural Committees all over the west bank and Gaza strip monitored the attacks of the Israeli occupation forces and settlers against the Palestinian agricultural sector in the West Bank during the month of September. This report documents Israeli bulldozers demolishing Palestinian agricultural facilities, in addition uprooting over 600 trees. This report documents demolition operations and military notices for more than 13 agricultural facilities, the demolition of two wells for water collection, the uprooting of more than 1400 trees, and the razing and seizing of more than 130 dunums, in a continuous escalation of land seizing and settlement expansion. Demolishing Agricultural Facilities Occupation forces demolishing houses in Yarza/ Jordan Valley • On September 02, 2020, the occupation forces demolished a 300-square-meter barracks in the area of Jebna in Masafer Yatta, Hebron. • On September 02, 2020, the occupation forces demolished a 50-cubic-meter water well in the village of Birin, west of Bani Naim town, to the east of Hebron. • On September 07, 2020, the Israeli occupation authorities delivered military demolition notices for against two barracks for livestock in the village of Kisan, east of Bethlehem. It is noteworthy that the 1 village of Kisan undergoes a fierce settlement attack, and is witnessing the largest settlement project in Bethlehem, which threatens to seize about 3,500 dunums. • On September 14, 2020, a military demolition notice was delivered for an 80-square-meter sheep pen, built of tin, in the village of Twana, to the east of Yatta, south of Hebron governorate. -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 24 – 30 January 2007 of Note This Week

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 24N –S 30 January 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 24 – 30 January 2007 Of note this week − Three Israeli civilians were killed and another injured by a Palestinian suicide bomber in the southern Israeli town of Eilat. Three Palestinians were killed, including two children, and 21 injured in the oPt by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). − Inter-factional fighting escalated significantly in the Gaza Strip. In total, 37 Palestinians were killed and 93 injured as a result of internal violence. A cease-fire agreement was brokered on 29 January but sporadic clashes have continued. Gaza Strip: − A 17 year-old Palestinian boy was killed and two others injured when the IDF opened fire from the border fence. IAF aircraft targeted an uninhabited Palestinian home east of Gaza city which the IDF claimed was housing a tunnel into Israel. An IAF aircraft also fired a rocket at a Palestinian rocket-launch site in Beit Lahia. − Palestinian militants opened fire at an IDF observation post on the border fence and fired eight homemade rockets towards Israel. No injuries were reported. − During the continuing internal violence unknown gunmen opened fire at the home of PA Foreign Minster Mahmoud Al Zahar. In two separate incidents stray bullets struck the back window of an UNRWA ambulance and vehicle.