Dunning and Nilekani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Identified for Afforestation in the Forest Limits of Mysuru District Μ

Land identified for afforestation in the forest limits of Mysuru District µ Bettahalli Guluvina Attiguppe Hosuru Hosuru Mudiguppe Munjanahalli Mundur Kallikoppalu Dodda Koppalu Kanchanahalli Chikka Bherya Kallikoppalu Tandre Salekoppalu Tandrekoppalu Sankanahalli Somanahalli Bherya Melur Haradanahali Bachahalli Badiganahalli Madapura Katnalu Kurubarahalli Sugganahalli Abburu Doddadahalli Ramapura Mudlabidu Elemuddanahalli Harumballikoppalu Basavanahalli Kallimuddanahalli Karatalu Lakkikuppe Yaladahalli Kodiyala Manugonahalli Hebsuru Harumballi Lakkikuppekoppalu Ankanahalli Kanagalu Saligrama Hosa Agrahara Sarguru Hale Mirle Tandere Gayanahalli Honnenahalli Kottayanakoppalu Cummanahalli Natnahalli Hanumanahalli Dodda Vaddaragudi Honnapura Alchanahalli Dodda Hanasoge Kanchinakere Pasupati Kakanahalli Subbayyanakoppalu Kedaga Chiknayakanahalli Adaguru PasupatikoppaluMavanuru Mirle Chikka Vaddaragudi Rajanabilugull Bichanahalli Galigekere Balluru C Koppalu Malnayakanahalli Ganganahalli Arjunahalli KD Kambipura Yaremanuganahalli Koluru Ganganahallikoppalu Chikka Hanasage Kaggala Adaguru Halaganahalli Chennamgere Ganganakuppe Kavalanahalli Bandahalli Kalyanapura Sannegaudanakoppalu Dammanahalli Byalakuppe Suragahalli Hadya Baluru Doddakoppalu Harinahalli Sakkare Dod Kamarhalli Kumarikoppalu Karadipura Nadappanahalli K.R.Nagar Badakanakoppalu Anivalu Meluru Halgegaudankoppalu Baluru Chapparadahalli Sangarashettihalli Maraduru Kanaganahalli Ambalare Dammanahallikoppalu Diddahalli Chunchanakatte Chik Kamarhalli Manchinahalli Maradur Koppalu Mayigaudanahalli -

HŒ臬 A„簧綟糜恥sµ, Vw笑n® 22.12.2019 Š U拳 W

||Om Shri Manjunathaya Namah || Shri Kshethra Dhamasthala Rural Development Project B.C. Trust ® Head Office Dharmasthala HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ, vw¯ºN® 22.12.2019 Š®0u®± w®lµu® îµ±°ªæX¯Š®N®/ N®Zµ°‹ š®œ¯‡®±N®/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛ‡®± wµ°Š® wµ°î®±N¯r‡®± ªRq® y®‹°£µ‡®± y®ªq¯ºý® D Nµ¡®w®ºruµ. Cu®Š®ªå 50 î®±q®±Ù 50 Oʺq® œµX®±Ï AºN® y®lµu®î®Š®w®±Ý (¬šµ¶g¬w®ªå r¢›Š®±î®ºqµ N®Zµ°‹/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ y®u®ï î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 25 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ î®±q®±Ù îµ±ªæX¯Š®N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ Hš¬.Hš¬.HŒ¬.› /z.‡®±±.› ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ‡µ²ºvSµ 3 î®Ç®Áu® Nµ©š®u® Aw®±„Â®î® î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 30 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ ) î®±±ºvw® œ®ºq®u® š®ºu®ý®Áw®NµÊ B‡µ±Ê ¯l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. š®ºu®ý®Áw®u® š®Ú¡® î®±q®±Ù vw¯ºN®î®w®±Ý y®äqµã°N®î¯T Hš¬.Hº.Hš¬ î®±²©N® ¯Ÿr x°l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. œ¯cŠ¯u® HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ A†Ãw®ºu®wµS®¡®±. Written test Sl No Name Address Taluk District mark Exam Centre out off 100 11 th ward near police station 1 A Ashwini Hospete Bellary 33 Bellary kampli 2 Abbana Durugappa Nanyapura HB hally Bellary 53 Bellary 'Sri Devi Krupa ' B.S.N.L 2nd 3 Abha Shrutee stage, Near RTO, Satyamangala, Hassan Hassan 42 Hassan Hassan. -

Mysuru Bar Association : Mysuru Taluk : Mysuru District : Mysuru

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : MYSURU BAR ASSOCIATION : MYSURU TALUK : MYSURU DISTRICT : MYSURU SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE BYRAPPA S MYS/15/55 S/O SIDDIAH 1 D NO.3108/B 4TH CROSS VIVEKANAND ROAD YADAVAGIRI EXTN MYSURU MYSURU 20 CHANDRASEKHAR H N MYS/30/59 S/O 2 1065 JAYA LAKSHMI VILAS ROAD CHAMARAJA PURAM . MYSURU MYSURU 570 005 GANGADHARAN H MYS/36/59 S/O RUDRAPPA 3 1089 VISHNUVARDHAN ROAD CHAMARAJAPURAM MYSURU MYSURU 570005 KANTHARAJA SETTY K V MYS/484/62 4 S/O KRISHNA SHETTY K V L-26 1ST STAGE KUVEMPU NAGAR MYSURU MYSURU 570 023 1/320 3/17/2018 KRISHNA IYENGAR M S MYS/690/62 S/O M V KRISHNA IYENGAR 5 NO.1296 IV TH WEST CROSS 3RD MAIN ROAD KRISHNAMURTHYPURAM MYSURU MYSURU 04 SHIVASWAMY S A MYS/126/63 6 S/O APPAJIGOWDA SARASWATHIPURAM MYSURU MYSURU THONTADARYA MYS/81/68 S/O B.S. SIDDALINGASETTY 7 B.L 208 12TH MAIN 3RD CROSS SARASWATHIPURAM MYSURU MYSURU 570009 SRINIVASAN RANGA SWAMY MYS/190/68 S/O V R RANGASWAMY IGENGAL 8 416 VEENE SHAMANNA'S STREET OLD AGRAHARA MYSURU MYSURU 570 004 SESHU YEDATORE GUNDU RAO MYS/278/68 9 S/O Y.V.GUNDURAO YEDATORE 447/A-4 1 ST CROSS JAYA LAXMI VILAS ROAD MYSURU MYSURU 570 005 2/320 3/17/2018 RAMESH HAMPAPURA RANGA SWAMY MYS/314/68 S/O H.S. RANGA SWAMY 10 NO.27 14TH BLOCK SBM COLONY SRIRAMPURA 2ND STAGE MYSURU MYSURU 570023 ASWATHA NARAYANA RAO SHAM RAO MYS/351/68 11 S/O M.SHAMARAO 1396 D BLOCK KUVEMPUNAGAR MYSURU MYSURU 570023 SREENIVASA NATANAHALLY THIMME GOWDA MYS/133/69 S/O THIMMEGOWDA 12 NO 22 JAYASHREE NILAYA 12TH CROSS V.V.MOHALLA MYSURU MYSURU 2 DASE GOWDA SINGE GOWDA MYS/255/69 13 S/O SINGE GOWDA NO. -

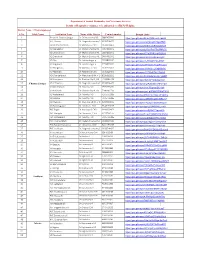

S.No. Taluk Name Institution Name Name of the Doctor Contact Number

Department of Animal Husbandry And Veterinary Services Details of Hospital Co-ordinates to be submitted to AH&VS Helpline District Name : Chamarajanagar S.No. Taluk Name Institution Name Name of the Doctor Contact number Google Links 1 Polyclinic Chamarajnagar Dr Chinnaswamy DD 9880450942 https://goo.gl/maps/5FBqSz5bomLLJaaA6 Polyclinic 2 VH , Harave Dr. Nagendra swamy C 9108514425 https://goo.gl/maps/xGkjMsqsEVSgp7Bd8 3 VH Santhemarahalli Dr.Nataraju.G CVO 9141328463 https://goo.gl/maps/qHhiTzwEKKUkyDTw7 4 VD Ganaganur Dr Mohan Shankar M, 9964691872 https://goo.gl/maps/Q3Sv6FnnFDoBPPu76 VO 5 VD Ummathuru Dr Mohan Shankar M, 9964691872 https://goo.gl/maps/bT1g2PMtCndYBUjG9 VO 6 VD Demahalli Dr Mohan Shankar M, 9964691872 https://goo.gl/maps/5runr2xcuQHEnoyX8 VO 7 VD Alur Dr Lakshmisagar p 7259810202 https://goo.gl/maps/j3e7MiwE5PDe9Sfz7 8 VD Kagalvadi Dr Lakshmisagar p 7259810202 https://goo.gl/maps/x5TewWvTcUa9AszCA 9 VD Honganuru Dr.Nataraju.G CVO 9141328463 https://goo.gl/maps/z8fHNHzzL19gMMrG6 10 VD Nagavalli Dr.Nataraju.G CVO 9141328463 https://goo.gl/maps/oT2DSzQ7Kv37itkNA 11 VD Chandakavadi Dr Manohara B M, V O 8296950231 https://goo.gl/maps/FUANuQ1zLAALYzxM7 12 VD Punajanur Dr Chethan Raj R, VO 7348982738 https://goo.gl/maps/i9DcxgP6BBwkajW67 13Chamarajanagar VD V.Chathra Dr. Nagendra swamy C 9108514425 https://goo.gl/maps/kqZAdsn5GJsHFUTQ9 14 VD Amachavadi Dr. Murthy, VO 7975773285 https://goo.gl/maps/okuufSJpxgoQLnJa8 15 VD Bisilavadi Dr Chethan Raj R, VO 7348982738 https://goo.gl/maps/yguLgVPWXDZWwEWJ6 16 VD Arakalavadi Dr. Murthy, VO 7975773285 https://goo.gl/maps/PRoYchJ2WpHW1QYh6 17 VD Udigala Dr. Murthy, VO 7975773285 https://goo.gl/maps/e8jbMW84A8bJSRC17 18 VD Maliyuru Dr Manohara B M, V O 8296950231 https://goo.gl/maps/Y7fyvQx1MauWH6Uo8 19 VD Badanaguppe Dr. -

1995-96 and 1996- Postel Life Insurance Scheme 2988. SHRI

Written Answers 1 .DECEMBER 12. 1996 04 Written Answers (c) if not, the reasons therefor? (b) No, Sir. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF (c) and (d). Do not arise. RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) (a) No, Sir. [Translation] (b) Does not arise. (c) Due to operational and resource constraints. Microwave Towers [Translation] 2987 SHRI THAWAR CHAND GEHLOT Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state : Construction ofBridge over River Ganga (a) the number of Microwave Towers targated to be set-up in the country during the year 1995-96 and 1996- 2990. SHRI RAMENDRA KUMAR : Will the Minister 97 for providing telephone facilities, State-wise; of RAILWAYS be pleased to state (b) the details of progress achieved upto October, (a) whether there is any proposal to construct a 1906 against above target State-wise; and bridge over river Ganges with a view to link Khagaria and Munger towns; and (c) whether the Government are facing financial crisis in achieving the said target? (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the time by which construction work is likely to be started and THE MINISTER OF COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI BENI completed? PRASAD VERMA) : (a) to (c). The information is being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) : (a) No, Sir. [E nglish] (b) Does not arise. Postel Life Insurance Scheme Railway Tracks between Virar and Dahanu 2988. SHRI VIJAY KUMAR KHANDELWAL : Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: 2991. SHRI SURESH PRABHU -

Chamarajanagar Taluk.Pdf

Sl No. Reg. No. Postal Address 1 1287 Reg No. 1287 Shri R Nageshappa At & Post-Demahalli, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 2 1483 Reg No. 1483 Shir D Basappa Agriculturist At & Post-Harave, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 3 1502 Reg No. 1502 Shir B C Nagappa Chikka Angadi Beedi, At & Post-Badanaguppe, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 4 2357 Reg No.2357 Sri Putta Nanjaiah Advocate Vice President AIVM Sabha Chamarajanagara 5 2358 Reg No. 2358 Shri K S Nagarajappa At & Post-Kodimale, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 6 2359 Reg No. 2359 Shri R S Nagabasavanna At & Post-Rajasamudra, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 7 2360 Reg No.2360 Shri S Puttaswamy, Ex-MLA Congress Office, Chamarajnagar-571313, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 8 2361 Reg No.2361 Shri K.S.Rajshekhar S/o Mahadevappa At & Post-Kempanapur, Tq & Dist- Chamarajnagar 9 2362 Reg No. 2362 Shri M T Mahadevappa At & Post-Madapura, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist Page 1 of 238 10 2363 Reg No. 2363 Shri Kodi K Shivanna (kade mane) At & Post-Hebbasuru, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 11 2364 Reg No.2364 Shri Guruswamy Advocate, Chamarajnagar-571313, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 12 2365 Reg No.2365 Shir Rajshekhar At & Post-Kodimale, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 13 2366 Reg No.2366 Shri K S Mahadevaswamy At & Post- Kagalawadi, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 14 2367 Reg No.2367 Shri Mahadevaiah S/o Mulemane Lingappa At & Post-Maleyuru, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 15 2368 Reg No.2368 Shri H M Mariswamy At & Post-Hebbasuru, Chamarajnagar Taluk & Dist 16 2369 Reg No.2369 Shri Siddamallappa At & Post-Basalawadi, -

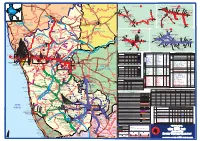

A1 SYSTEM MAP 2021.Cdr

TO TO PUNE (PA) LATUR TO Eó®Ò¨ÉxÉMÉ® TO NANDED ROHA 0.000, 191.590(CST) DAUND JN.(DD) PARBHANI JN. ÊxÉVÉɨÉɤÉÉn 267.180(CST) KARIMNAGAR TO ENLARGEMENT AT A C NIZAMABAD MUMBAI ENLARGEMENT AT =º¨ÉÉxÉɤÉÉn HOSAPETE JN. (HPT) 143.261, 0.000(AVC) TORANAGALLU JN. (TNGL) NH 7 BAYALU VODDIGERI OSMANABAD 141.798 (BYO)161.530 175.700, 0.000(RNJP) MARMAGAO HARBOUR TO TO PAPINAYAKANAHALLI (MRH) 111.870 BALLARI CANTT. KURDUWADI JN. (KWV) MIRAJ HUBBALLI JN. (PKL)156.510 DAROJI (BYC) 202.940 376.28(CST) GADIGANURU (DAJ) 181.270 KONKAN RAILWAY MUNIRABAD (MRB) 137.290 (GNR)168.470 BELLARY CANTONMENT (H) VASCO-DA-GAMA 204.100 BARAMATI TO HOSAPETE BYE PASS LINE INDIA (VSG) 108.458 2.510 310.880(CST) KAZIPET JN. BALLARI JN. (BAY) TUNGA BHADRA DAM (TBDM) 5.020 KUDATINI 208.060, 0.000(RDG) KARIGANURU (KDN)188.230 DABOLIM (H) SWR LIMIT XX VERNA (KGW)149.605 174.105 KHED (DBM) 103.384 VYASANAKERI (VYS) 10.300 ºÉiÉÉ®É BIDAR (BIDR) TORANAGALLU 1.658 212.000 SOLAPUR (SUR) ¨ÉänE SWR LIMIT VYASA COLONY JN(VC) NH 9 ¤ÉÒn® 90.780 92.500 BYE PASS LINE TO BHIMA 454.970, 299.440(GDG) 16.218,0.000(SMLI) BALLARI SATARA SANKAVAL GUNTAKAL JN. XX RIVER MEDAK SWR LIMIT MAJORDA JN. (MJO) GUNJI (GNJ) MARIYAMMANAHALLI (H) (MMI) 21.930 BANNIHATTI BYE PASS LINE BIDAR XX (SKVL) 100.391 572.990 ¶ÉÉä±ÉÉ{ÉÖ® XX 109.110 (BNHT) 9.020 HOTGI JN. (HG) 435.730(ROHA/KRCL) HAMPAPATNAM (H) RAMGAD HADDINAGUNDU XX NH 9 470.040, 284.090(GDG) 91.500(LD) (HPM) 33.170 (RMGD) 13.122 (HDD) 214.680 SOLAPUR CANSAULIM TINAIGHAT TO OBALAPURAM CHIPLUN SWR LIMIT SANJUJE- DA- AREYAL (H) 0 (CSM) 95.873 (TGT) 11.640 HUBBALLI YESHWANTH NAGAR (OBM) 15.40 281.900 HUMNABAD XX (SJDA)79.655 SULERJAVALGE (H) (SLGE) 271.520 CASTLEROCK (YTG) 23.992 TPURA XX VALI (H) (SRVX) RANJI RAM (HMBD) 37.207 SURA (CLR) 24.500 HAGARIBOMMANAHALLI SOMALAPU 439.020, 88.210(LD) (RNJP) 23.020 30.860 TADWAL (TVL) 264.180 (HBI) 43.470 (SLM) SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY Eó±É¤ÉÙ®MÉÒ SECUNDERABAD JN. -

Mysore-570011 Mysore Dist 2 Reg No

SL NO. REG NO NAME & ADDRESS 1 Reg No. 2 Reg No. 2 Shri GR Prameshwarappa NO.216, Gyanajythi, Neethimarga Siddarthanagar, Mysore-570011 Mysore Dist 2 Reg No. 3 Reg No. 3 Shri NS Manjunath NO.318, 4th Main Road Subhashnagar, Mysore-570007 Mysore Dist 3 Reg No. 4 Reg No. 4 Shri A Vinay Kumar NO.67, 3rd Main Road Subhashnagar, Mysore-570007 Mysore Dist 4 Reg No. 5 Reg No. 5 Shri A M Mahadevaiah No.30, 3rd Cross, Tank Road Narasimharaj Mohalla, Mysore - 570007 Mysore Dist 5 Reg No. 6 Reg No. 6 Shri P M Basavaraju NO.581/A, 4th Main Road, 2/A Cross Narasimharaj Mohalla, Mysore -570007 Mysore Dist 6 Reg No. 7 Reg No. 7 Shri B Sadashiv NO.4594, 4th Cross, St Mary's Main Road Narasimharaj Mohalla, Mysore -570007 Mysore Dist 7 Reg No. 8 Reg No. 8 Shri K.N. Nagarajan NO.4517, St Mary's Main Road Narasimharaj Mohalla, Mysore - 570007 Mysore Dist 8 Reg No. 14 Reg No. 14 Smt Gowramma NO.905/1, 4th Cross, Sunnada Keri KR Mohalla, Mysore - 570004 Mysore Dist 9 Reg No. 15 Reg No. 15 Smt MA Neelambika NO.242, Uttaradhimatta Fort MOhalla, Mysore -570004 Mysore Dist 10 Reg No. 18 Reg No. 18 Shri S Y Sadashivamurthy NO.420, Udayagiri Road Kuvempunagar, Mysore -570023 Mysore Dist 11 Reg No. 19 Reg No. 19 Shri UK Basavanna NO.362, Alanahalli Layout T Narasipura Road, Mysore - 570011 Mysore Dist 12 Reg No. 21 Reg No. 21 Shri Renkaradhya NO.561, 2nd Main Road, 5th Cross, 1st Stage Vijayanagar, Mysore -570017 Mysore Dist 13 Reg No. -

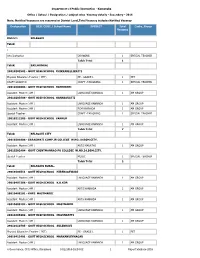

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka Office / School / Designation / subject wise Vacancy details - Secondary - 2016 Note: Notified Vacancies are reserved at District Level,Total Vacancy includes Notified Vacancy Designation DISE CODE / School Name SUBJECT Total Cadre_Group Vacancy District: BELAGAVI Taluk: - Arts Instructor DRAWING 1 SPECIAL TEACHER Taluk Total 1 Taluk: BAILHONGAL 29010202502 - GOVT HIGHSCHOOL CHIKKABELLIKATTI Physical Education Teacher ( PET) PE - GRADE 1 1 PET CRAFT GRADE II CRAFT -TAILORING 1 SPECIAL TEACHER 29010204904 - GOVT HIGHSCHOOL HANNIKERI Assistant Master ( AM ) LANGUAGE KANNADA 1 AM GROUP 29010205604 - GOVT HIGHSCHOOL HANABARATTI Assistant Master ( AM ) LANGUAGE KANNADA 1 AM GROUP Assistant Master ( AM ) PCM KANNADA 1 AM GROUP Special Teacher CRAFT -TAILORING 1 SPECIAL TEACHER 29010212205 - GOVT HIGHSCHOOL VANNUR Assistant Master ( AM ) LANGUAGE KANNADA 1 AM GROUP Taluk Total 7 Taluk: BELAGAVI CITY 29010301904 - SARASWATI COMP JR COLLEGE W.NO.19.BGM.CITY. Assistant Master ( AM ) ARTS MARATHI 1 AM GROUP 29010302404 - GOVT CHINTMANRAO PU COLLEGE W.NO.24.BGM.CITY. Special Teacher MUSIC 1 SPECIAL TEACHER Taluk Total 2 Taluk: BELAGAVI RURAL. 29010404511 - GOVT HIGHSCHOOL HIREBAGEWADI Assistant Master ( AM ) LANGUAGE KANNADA 1 AM GROUP 29010407206 - GOVT HIGHSCHOOL K.K.KOP. Assistant Master ( AM ) ARTS KANNADA 2 AM GROUP 29010408101 - KHPS MASTMARDI Assistant Master ( AM ) ARTS KANNADA 1 AM GROUP 29010408102 - GOVT HIGHSCHOOL MASTMARDI Assistant Master ( AM ) LANGUAGE KANNADA 1 AM GROUP 29010408202 - GOVT -

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

Ethnic Quotas and Political Mobilization APPENDIX APSR R&R

Online Appendix for “Ethnic Quotas and Political Mobilization: Caste, Parties, and Distribution in Indian Village Councils” Thad Dunning (Yale) and Janhavi Nilekani (JFK School) August 14, 2012 This appendix contains tables and other supplementary materials to which we refer in our paper. Table of Contents Sampling Design................................................................................................................................................2 District selection........................................................................................................................................................2 Sub-district (block) selection ................................................................................................................................2 Village council selection..........................................................................................................................................2 Village selection (citizen surveys) .......................................................................................................................2 Respondent selection (citizen surveys).............................................................................................................2 Table A1. Additional Example of Scheduled Caste Reservation History.................................................4 Additional Balance Tests.................................................................................................................................5 Table A2. Additional -

Re-DSAP November 2012

SLBC KARNATAKA: GRAM PANCHAYAT WISE REVISED SERVICE AREA PLAN OF THE DISTRICT: CHAMARAJANAGARA DISTRICT Name of the District: CHAMARAJANAGA ALL BLOCKS Existing or Proposed Village Population Of Post Identified Name and Banking outlet details Names of the Revenue Code as the Revenue Office/S Sl. place/village of 1600 Name Of alloted Bank Contact No. designation of Bank Week day(s) fixed Sl. Name of Gram Panchayat (Branch/ BC/ USB/ Mobile Name of the BCA Villages forming the used in Villages as ub-post No. or more population with Branch name of BCA Officer identified for for visits No. Van/ATM etc) with name Gram Panchayat 2011 per Census Office (2001 census) weekly visits of Bank Census 2001 YES/NO 1 2 3 4 4a 4b 4c 5 6 7 8 1 MADAPURA Handarakalli SBM CHAMARAJANAGAR BC(SBM CR NAGARA) MAHESHA N 9986396331 CHANDRASHEKARA WEEKLY ONCE 1 Handarakalli 619659 2116 2 Masagapura 619662 888 3 Kadahalli 619663 1200 4 Kiragasur 619657 876 Madapura 5 Madapura 619658 1655 YES SBM, ADB 2 DEMAHALLI 1 Banahalli 619607 1086 SANTHEMARAHALLI 2 Kamaravadi 619610 1439 3 Mudala Agrahara 619613 1476 Demahalli 4 Demahalli 619611 1933 YES SBM, ADB 3 KEMPANAPURA 1 Singanapura 619623 648 SANTHEMARAHALLI 2 Kannegala 619624 1381 Kempanapura BC(SBM ADB Smhally) GIREESHA 9844128881 SUKUMAR WEEKLY ONCE 3 Kempanapura 619620 4722 YES SBM, ADB 4 SANTHEMARAHALLI 1 Basavatti 619618 498 SANTHEMARAHALLI 2 Desavalli 619617 873 3 Heggavadipura 619616 1017 Branch 4 Santhemarahalli 619619 2800 YES 5 Kavudavadi 619609 1415 YES 6 Thelanur 619608 1209 5 KUDERU SBM KUDERU 1 Heggavadi