Why Environmental Due Diligence Matters in Mineral Supply Chains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennsylvania State University Center for Critical Minerals Final

The Pennsylvania State University Center for Critical Minerals Final Report on Cobalt Production in Pennsylvania: Context and Opportunities PREPARED FOR LEONARDO TECHNOLOGIES LLC., PREPARED BY Peter L. Rozelle Feifei Shi Mohammad Rezaee Sarma V. Pisupati Disclaimer This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. ii Executive Summary Cobalt is a critical mineral as defined by the U.S. Department of the Interior in response to Executive Order 13817 (2017). Cobalt metal is used in superalloys required in the hot gas path of stationary gas turbines and jet engines, as well as in samarium cobalt magnets, the domestic production capability of which was found to be essential to the National Defense under Presidential Determination 2019-20. Cobalt compounds are used in lithium-ion batteries, as are manganese compounds. The Defense Industrial Base Report, in response to Executive Order 13806 (2017), expressed concerns regarding the U.S. -

World Bank Document

Document of The 'World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY ¢ ' 6 K Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 2149b-CO STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized (COLOMBIA CERRO MATOSO NICKEL PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Septemiber 24, 1979 Public Disclosure Authorized Industrial Projects Department This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit: Colombian Peso (Col$) Col$1 = 100 centavos (ctv) Currency Exchange Rates Col$42.40 = US$1.0 Col$1,000 US$23.58 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1 meter (m) = 3.281 feet (ft) 1 kilometer (km)3 0.622 miles (mi) 3 1 cubic meter (m ) 35.315 cubic feet (ft ) "I= 264.2 US gallons (gal) f = 6.29barrels (bbl) 1 metric ton (MT) = 2,206 pounds (lb) 1 metric ton (MT) = 1.1 short tons (st) 1 dry metric ton (DMT) = 1.1 dry short tons (dst) 1 wet metric ton (WMT) 1.1 wet short tons (wst) 1 kilowatt (kW) - 1,000 watts 1 Megawatt (MW) 1,000 kilowatts 1 Megavoltampere (MVA) = 1,000 kilovoltamperes (kVA)6 1 Gigawatthour (GWh) 1,000,000 kilowatthours (10 kWh) 1 kilovolt (kV) 1,000 volts GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS CARBOCOL - Carbones de Colombia, S.A. CMSA - Cerro Matoso, S.A. COLPUERTOS - Empresa P'uertosde Colombia CONICOL - Compania de Niquel Colombiano, S.A. CONPES - Consejo de Politica Economica y Social CORELCA - Corporacion Electrica de la Costa Atlantica DNP - Departamento Nacional de Planeacion ECOMINAS - Empresa Colombiana de Minas ECONIQUEL - Empresa Colombiana de Niquel, Ltda. -

Overview of the Nickel Market in Latin America and the Caribbean

INSG SECRETARIAT BRIEFING PAPER April 2021 – No.35 Overview of the Nickel market in Latin America and the Caribbean Ricardo Ferreira, Director of Market Research and Statistics Francisco Pinto, Manager of Statistical Analysis 1. Introduction At the suggestion of the Group’s Brazilian delegation, it was agreed by members that a report, based on INSG Insight No. 26, published in November 2015 entitled “An overview of the nickel industry in Latin America”, be prepared by the secretariat. This would include an update of the operations that resumed production (e.g. Falcondo in the Dominican Republic), and also discuss how the emerging battery market might influence nickel usage in the region as well as the possibility of nickel scrap usage. This detailed and comprehensive Insight report, the 35th in the series of INSG Insight briefing reports, provides members with the results of that research work. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the nickel producing countries are Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Guatemala and Venezuela. The Dominican Republic stopped nickel mining and smelting in October 2013 but resumed production at the beginning of 2016. Venezuela has not produced since mid-2015. All of these countries mine nickel and process it further to produce intermediate or primary nickel – mainly ferronickel. Most of the mined ore is processed within each country, and then exported to overseas markets, but Brazil and Guatemala also export nickel ore. In terms of usage only Brazil and Mexico are relevant regarding the global nickel market. The first section of this report briefly describes existing nickel deposits in the region. -

Rebel Attacks on Nickel Ore Mines in the Surigao Del Norte Region

Mindanao, Philippines – rebel attacks on nickel ore mines in the Surigao del Norte region The attacks On 3 October 2011, three mining firms located in and around Claver town in the Surigao del Norte region of Mindanao, Philippines were attacked by the rebel group known as the New People’s Army (NPA). It was reported that the attacks were prompted by a refusal of the mining firms to pay a "revolutionary tax" demanded by the NPA. The affected mining firms are the Taganito Mining Corporation (TMC), Taganito HPAL Nickel Corporation and Platinum Group Metals Corporation (PGMC)1. According to news reports and Gard’s local correspondent in the Philippines, some 300 NPA rebels wearing police/military uniforms staged coordinated strikes on the three mining facilities. The rebels attacked TMC’s compound first, burning heavy equipment, service vehicles, barges and buildings. Other rebel groups simultaneously attacked the nearby PGCM and Taganito HPAL compounds. Unconfirmed reports indicate that, unfortunately, casualties were also experienced during the attacks. All foreign vessels anchored near Taganito at the time of the attacks left the anchorage safely. The current situation The Philippine Government has stated that the situation is now contained and has deployed additional troops in the area to improve security and pursue the NPA rebels. However, according to Gard’s local correspondent in the Philippines, threats of further attacks made by the NPA in a press release are believed by many to be real. According to the latest press releases (Reuters on 5 October), Nickel Asia Corporation has resumed operations at its biggest nickel mine TMC and expects to ship ore in the next three weeks. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

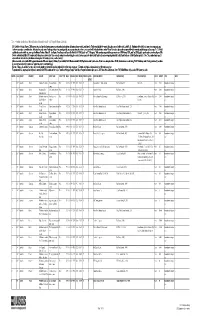

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

DOGAMI MP-20, Investigations of Nickel in Oregon

0 C\1 a: w a.. <( a.. en ::::> 0 w z <( __j __j w () en � INVESTIGATIONS OF NICKEL IN OREGON STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOL.OGY AND MINERAL. IN OUSTRIES DONAL.D .A HUL.L. STATE GEOLOGIST 1978 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 1069 State Office Building, Portland, Oregon 97201 MISCELLANEOUS PAPER 20 INVESTIGATIONS OF NICKEL IN OREGON Len Ramp, Resident Geologist Grants Pass Field Office Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Conducted in conformance with ORS 516.030 . •. 5 1978 GOVERNING BOARD Leeanne MacColl, Chairperson, Portland Talent Robert W. Doty STATE GEOLOGIST John Schwabe Portland Donald A. Hull CONTENTS INTRODUCTION -- - ---- -- -- --- Purpose and Scope of this Report Acknowledgments U.S. Nickel Industry GEOLOGY OF LATERITE DEPOSITS - -- - 3 Previous Work - - - - --- 3 Ultramafic Rocks - ----- --- 3 Composition - - -------- - 3 Distribution ------ - - - 3 Structure - 3 Geochemistry of Nickel ---- 4 Chemical Weathering of Peridotite - - 4 The soi I profile ------- 5 M i nero I ogy -- - ----- 5 Prospecting Guides and Techniques- - 6 OTHER TYPES OF NICKEL DEPOSITS - - 7 Nickel Sulfide Deposits- - - - - - 7 Deposits in Oregon 7 Other areas --- 8 Prospecting techniques 8 Silica-Carbonate Deposits - -- 8 DISTRIBUTION OF LATERITE DEPOSITS - ------ 9 Nickel Mountain Deposits - - ------ --------- 9 Location --------------- --- 9 Geology - ------- ----- 11 Ore deposits ----------- - -- 11 Soil mineralogy - ------- 12 Structure --- ---- ---- 13 Mining and metallurgy ------------ ---- 13 Production- -

Efectos Del Auge Minero En Las Exportaciones No Tradicionales Colombianas (1980-2013)

EFECTOS DEL AUGE MINERO EN LAS EXPORTACIONES NO TRADICIONALES COLOMBIANAS (1980-2013). ANA MILETH DE LA ENCARNACIÓN ANGULO JESSIKA ESTEFANÍA MORENO OSSA AGUSTÍN PARRA RAMÍREZ UNIVERSIDAD LA GRAN COLOMBIA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y ADMINISTRATIVAS PROGRAMA DE ECONOMÍA BOGOTÁ DC 2014 EFECTOS DEL AUGE MINERO EN LAS EXPORTACIONES NO TRADICIONALES COLOMBIANAS (1980-2013). ANA MILETH DE LA ENCARNACIÓN ANGULO JESSIKA ESTEFANÍA MORENO OSSA AGUSTÍN PARRA RAMÍREZ Trabajo de grado para obtener el título de economista. ASESOR: NELSON MANOLO CHAVEZ MUÑOZ ECONOMISTA UNIVERSIDAD LA GRAN COLOMBIA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y ADMINISTRATIVAS PROGRAMA DE ECONOMÍA BOGOTÁ DC 2014 NOTA DE ACEPTACIÓN __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ Firma del jurado __________________________ Firma del jurado Bogotá, Julio 2014 DEDICATORIA A mi tía, hermanos, familia y amigos Que han hecho parte de los acontecimientos Más importantes de mi vida Ana Mileth De La Encarnación Angulo A mi madre, hijo, esposo y seres queridos Que ayudaron a cumplir un sueño más En mi vida personal. Jessika Estefanía Moreno Ossa A mis padres, hermanos, amigos y seres queridos Que han tenido participación activa en esta travesía Y por los que vale pensar y construir un mundo mejor. Agustín Parra Ramírez AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradecemos principalmente a la Universidad La Gran Colombia y a la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Administrativas por abrirnos las puertas del mundo académico, profesional e investigativo, igualmente extendemos nuestros más sinceros agradecimientos al Docente Nelson Manolo Chávez Muñoz por la asesoría metodológica, teórica, conceptual y propositiva y a la Docente María Inés Barbosa Camargo quien fue un apoyo incondicional en el desarrollo de la parte econométrica de la investigación. -

La Mineria En Colombia: Impacto Socioeconómico Y Fiscal

FUNDACIÌN PARA LA EDUCACIÌN SUP ERIOR Y EL DESARROLLO INFORME FINAL LA MINERIA EN COLOMBIA: IMPACTO SOCIOECONÓMICO Y FISCAL Proyecto de la Cámara ASOMINEROS de la ANDI Elaborado por FEDESARROLLO Director del proyecto: Mauricio Cárdenas Mauricio Reina Investigadores asistentes: Eliana Rubiano, Sandra Rozo y Oscar Becerra Bogotá, Abril 8 de 2008 TABLA DE CONTENIDO INTRODUCCIÓN Y RESUMEN EJECUTIVO I. MINERÍA Y DESARROLLO: UN NUEVO PARADIGMA................................ 12 1. CRECIMIENTO ECONÓMICO Y AUGE MINERO EN EL MUNDO .......... 13 2. MINERIA Y DESARROLLO. EL PARADIGMA TRADICIONAL ............... 17 3. MINERÍA Y DESARROLLO: UN PARADIGMA ALTERNATIVO ............. 19 Alternativas conceptuales....................................................................................... 19 El ejemplo de algunos casos exitosos..................................................................... 20 Minería y desarrollo: elementos para una estrategia eficaz.................................. 24 II. LA MINERÍA EN COLOMBIA ............................................................................ 26 1. ANTECEDENTES HISTÓRICOS ................................................................... 27 2. DESEMPEÑO RECIENTE DE LA MINERIA ................................................. 28 Producción y empleo .............................................................................................. 29 Exportaciones e Inversión Extranjera Directa....................................................... 30 Ingresos de la Nación............................................................................................ -

INDEPENDENT TECHNICAL REPORT and RESOURCES ESTIMATION on the EL ALACRAN COPPER GOLD DEPOSIT Department of Cordoba, Colombia

INDEPENDENT TECHNICAL REPORT AND RESOURCES ESTIMATION ON THE EL ALACRAN COPPER GOLD DEPOSIT Department of Cordoba, Colombia For Cordoba Minerals, 200 Burrard Street, Suite 650, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, V6C 3L6 Prepared by Mr. Ian Taylor, BSc(Hons), GCert Geostats. MAusIMM (CP) Dr. Stewart H Redwood, PhD, FIMMM Effective Date: 27 October 2016 Signature Date: 5 January 2017 Reference: MA1604-3-3 Mining Associates Pty Ltd ABN 29 106 771 671 Redwood Exploration & Discovery Inc. Level 4, 67 St Paul’s Terrace PO Box 0832-1784 Spring Hill QLD 4004 AUSTRALIA World Trade Center T 61 7 3831 9154 Panama City, REPUBLIC OF PANAMA F 61 7 3831 6754 W www.miningassociates.com.au Independent Technical Report And Resources Estimation On The El Alacran Copper Gold Deposit El Alacran Deposit. 5 January 2017 TABLE OF CONTENT DEPARTMENT OF CORDOBA, COLOMBIA .................................................................................... I TABLE OF CONTENT ....................................................................................................................II 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 12 2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 16 2.1 PURPOSE OF REPORT ........................................................................................................................ 16 2.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND PURPOSE ............................................................................................ -

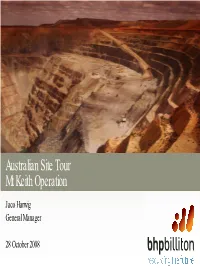

Mt Keith Presentation

Australian Site Tour Mt Keith Operation Jaco Harwig General Manager 28 October 2008 Important notices Reliance on third party information The views expressed here contain information that have been derived from publicly available sources that have not been independently verified. No representation or warranty is made as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information. This presentation should not be relied upon as a recommendation or forecast by BHP Billiton. Forward looking statements This presentation includes forward-looking statements within the meaning of the U.S. Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 regarding future events and the future financial performance of BHP Billiton. These forward-looking statements are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this presentation. For more detail on those risks, you should refer to the sections of our annual report on Form 20- F for the year ended 30 June 2008 entitled “Risk factors” , “Forward looking statements” and “Operating and financial review and prospects” filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. No offer of securities Nothing in this release should be construed as either an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell BHP Billiton securities in any jurisdiction. Cautionary Note to US Investors The SEC generally permits mining companies in their filings with the SEC to disclose only those mineral deposits that the company can economically and legally extract. -

The Cobalt Empire

! " The Wire China # Customize + New WP Engine Quick Links $ Edit Post Leaky Paywall Forms Howdy, David Barboza % Te Wire China About Us Archives Sections Your account Log out | ( | # " $ COVER STORY Te Cobalt Empire China controls much of the world’s supply of cobalt. Will it give the country an insurmountable edge in developing electric vehicles? BY TIM DE CHANT — OCTOBER 18, 2020 " # $ % & ' Illustration by Sam Ward esla’s “Battery Day” in Fremont, California, this past September felt like Lollapalooza for energy nerds. As record-breaking wildfres burned just six miles away,T underscoring Tesla’s mission to rid the world of climate change-causing fossil fuels, the electric vehicle company organized an hour-long celebration of lithium-ion batteries — one of a handful of technological breakthroughs that have made low carbon policies possible. On a giant outdoor stage, Elon Musk, Tesla’s co-founder and chief executive and Drew Baglino, a senior vice president, wore black t-shirts with a close-up image of Tesla’s new battery structure as they waxed poetic about the chemistry of lithium ion batteries. With energy-dense, durable and versatile cells, the nearly 50-year-old lithium ion battery now powers everything from laptops and smartphones to electric vehicles. Te battery’s inventors — John B. Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino — even won the Nobel Prize in chemistry last year. Companies around the world are now racing to build ever larger packs to store cheap and abundant wind and solar power. “Time really matters,” Musk said. “Tis presentation is about accelerating the time to sustainable energy.” Indeed, if you think lithium ion batteries are everywhere today, just wait until tomorrow. -

NICKEL by Peter H

NICKEL By Peter H. kuck Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Barbara J. McNair, statistical assistant, and the world production tables were prepared by Glenn J. Wallace, international data coordinator. Stainless steel accounted for more than 60% of primary nickel A total of 23.70 billion of the cupronickel clad coins was minted consumption in the world (Falconbridge limited, 2005a, p. between December 998 and December 2004. Between 30 ). However, in the United States, this percentage was only billion and 50 billion quarters will have been minted when 44% because of the relatively large number of specialty metal the program ends in December 2008, down somewhat from industries and readily available stocks of scrap. cupronickel previous forecasts. Since each coin weighs 5.67 grams (g) and alloys, electroless plating, electrolytic plating, high-temperature contains 8.33% nickel, ,34 t of nickel ended up in the five nickel-chromium alloys, naval brasses, and superalloys commemoratives released in 2004. and related aerospace alloys are some of the specialty uses. The U.S. Mint began releasing the new golden-colored dollar Increasing amounts of nickel metal foam are being used in the coin in January 2000. Between January 2000 and December 2003, manufacture of rechargeable batteries. .44 billion dollar coins were minted. An additional 5.3 million Nickel in excess of 8% is needed to produce the austenitic were made in 2004. The dollar coin contains 2.0% nickel. The microstructure in 300-series nonmagnetic stainless steels. The coin, which weighs 8.1 g, is clad with pure copper metallurgically nickel content of some austenitic grades can be as high as 22%.