(2013): EU Accession and Civil Society Empowerment: the Case of Maltese Engos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

Chapter 17: Tax Treaties

Chapter 17 Tax Treaties www.pwc.com/mt/doingbusiness Doing Business in Malta Tax treaty policy Since the mid-seventies Malta has sought to expand its However, the tax levied on the companies under the Income tax treaty network. Most of Malta’s treaties are based Tax Act in such situations will be directly limited to 15% on the OECD model although some treaties (particularly as if the treaty rate applied to the company profits. Rather older ones) contain some material variations therefrom. than a refund on the payment of dividends the investors Some of them include special tax incentives for foreign can therefore qualify for the reduced rate at the company enterprises setting up manufacturing establishments in level at the time that the profits are derived and without Malta. These consist typically in low tax rates on dividends any obligation to distribute the profits to benefit from the arising in Malta supported by tax sparing provisions. Malta’s reduced tax rate. Maltese domestic law also provides that economic development, and particularly the growth in its no tax is payable by non-residents on interest and royalties financial services sector, expanded the scope for tax treaties arising in Malta, subject to certain conditions (see Chapter and in fact currently Malta has over 70 double taxation 11) and, as stated above, this rule applies irrespective of the agreements with almost all the important OECD countries. treaty provisions dealing with withholding taxes on these The current list of tax treaties is given in Appendix VII. categories of income. Similarly, no tax is payable by non- A tax treaty concluded by Malta becomes law by Ministerial residents on capital gains arising on transfers of company order and the provisions arising therefrom apply shares or securities, except where such gains are derived notwithstanding any provisions to the contrary under from the transfer of shares or securities in companies whose Maltese domestic tax law. -

Annual Report 2006

89 MMiinniissttrryy ooff FFiinnaannccee _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Annual Reports of Government Departments ~ 2006 Ministry of Finance 90 Special Projects Division BACKGROUND The Special Projects Office has the function to undertake and implement a wide variety of initiatives some of which are of a corporate nature and others involving specific Ministry of Finance departments. The major corporate projects undertaken in the year under review were related to overseeing the development of: (a) Accrual Accounting; (b) eProcurement; and (c) eArchiving. Other assignments undertaken during the period under review range from the organisational reform of the revenue earning departments within the Ministry of Finance to the activities of the Co-ordinating Task Force for Own Resources. ACCRUAL ACCOUNTING Work is continuing on the introduction of accrual accounting at all ministries and their respective government departments. Accrual accounting will have a major impact on the way the internal financial business of Government will be conducted, particularly in areas of asset management and the management of debtors and creditors. This financial reform process will cross ministerial and departmental organisational boundaries and have a major influence on the departmental processes related to their day-to- day financial administration. Accrual accounting will provide more meaningful financial information that will enhance the quality of the Government's financial decision-making -

Doing Business in Malta

www.pwc.com/mt Doing Business in Malta A guide to doing business and investing in Malta October 2012 2013 Doing Business in Malta 1 Contents Foreword Chapter 1: Malta - A Profile 5 Chapter 2: Business and Investment Environment 13 Chapter 3: Investment Incentives 18 Chapter 4: Direct Foreign Investment 30 Chapter 5: Regulatory Environment 39 Chapter 6: Banking, Investment and Insurance Services 44 Chapter 7: Exporting to Malta 51 Chapter 8: Business Entities 54 Chapter 9: Labour Relations and Social Security 66 Chapter 10: Accountancy and Audit Requirements and Practices 74 Chapter 11: Tax System 84 Chapter 12: Tax Administration 94 Chapter 13: Taxation of Companies and Individuals 103 Chapter 14: Partnerships and other entities 113 Chapter 15: Taxation of Individuals 121 Chapter 16: Indirect Taxation 128 Chapter 17: Tax Treaties 136 2 PwC Appendix I - Qualifying companies for Investment Tax Credits 140 Appendix II - Capital Allowances 144 Appendix III - Corporate Tax Calculation 145 Appendix IV - Individual Tax Rates 146 Appendix V - Individual Tax Calculation 148 Appendix VI - Duty Documents and Transfer Act 149 Appendix VII - Tax treaties in force as at August 2011 150 2013 Doing Business in Malta 3 Foreword The Guide has been prepared for the assistance of those interested in doing business in Malta. It does not cover exhaustively the subjects it treats but is intended to answer in a broad manner some of the key questions that may arise. Before taking specific decision or in dealing with specific problems it will often be necessary to refer to the relevant laws, regulations and decisions and to obtain appropriate advice. -

Doing Business in Malta 2016

Doing business in Malta 2016 In association with: Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 – Country profile ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Legal overview ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Conducting business in Malta ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Tax system ................................................................................................................................................................................11 Labour ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Audit ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 21 Trade ........................................................................................................................................................................................ -

COMPLETING YOUR TAX RETURN a Step-By-Step Guide

COMPLETING YOUR TAX RETURN A Step-by-Step Guide Basis YYeearar 2020 Ye ar of Assessment 2021 1 2 This information booklet has been produced by the Office of the Commissioner for Revenue to help you fill in your tax return for the basis year 2020 in a complete and correct manner. Please note that the booklet is a guide only and has no legal force whatsoever. For further information: • Visit our website: www.cfr.gov.mt • Call: Freephone 153 • Email: [email protected] The Office of the Commissioner for Revenue uses the information provided to process your Income Tax Return and Self-Assessment in accordance with the Income Tax Acts and subsidiary legislation. We may check information provided by you, or information about you provided by a third party, with other information held by us. We will not disclose information about you to anyone outside the Office of the Commissioner for Revenue unless permitted by law. The Office of the Commissioner for Revenue treats your personal information in accordance with the Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation) and the Data Protection Act (Cap 586) to protect your privacy. Any queries may be addressed to The Data Controller, Office of the Commissioner for Revenue, Floriana, FRN 1700. 3 CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 6 YOUR TAX RETURN: THE SELF-ASSESSMENT SYSTEM 6 MARRIED COUPLES 8 SEPARATED / DIVORCED COUPLES 9 PARENTS 9 SINGLE PARENTS 9 PERSONAL DETAILS 10 OTHER INFORMATION 11 EMOLUMENT AND BUSINESS INCOME 13 1. Employment or Office 13 2. Trade, Business, Profession or Vocation 14 3. Pensions and Social Security Benefits 16 4. -

2016 Country Review

Malta 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 3 Malta 4 Europe 5 Chapter 2 7 Political Overview 7 History 8 Political Conditions 9 Political Risk Index 16 Political Stability 30 Freedom Rankings 45 Human Rights 57 Government Functions 59 Government Structure 61 Principal Government Officials 65 Leader Biography 68 Leader Biography 68 Foreign Relations 70 National Security 74 Defense Forces 75 Chapter 3 77 Economic Overview 77 Economic Overview 78 Nominal GDP and Components 96 Population and GDP Per Capita 98 Real GDP and Inflation 99 Government Spending and Taxation 100 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 101 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 102 Data in US Dollars 103 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 104 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 106 World Energy Price Summary 107 CO2 Emissions 108 Agriculture Consumption and Production 109 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 111 Metals Consumption and Production 112 World Metals Pricing Summary 115 Economic Performance Index 116 Chapter 4 128 Investment Overview 128 Foreign Investment Climate 129 Foreign Investment Index 133 Corruption Perceptions Index 146 Competitiveness Ranking 157 Taxation 166 Stock Market 167 Partner Links 167 Chapter 5 168 Social Overview 168 People 169 Human Development Index 170 Life Satisfaction Index 174 Happy Planet Index 185 Status of Women 194 Global Gender Gap Index 197 Culture and Arts 207 Etiquette 208 Travel Information 208 Diseases/Health Data 217 Chapter 6 223 Environmental Overview 223 Environmental Issues 224 Environmental Policy 224 Greenhouse Gas Ranking 226 Global Environmental Snapshot 237 Global Environmental Concepts 248 Malta Chapter 1 Country Overview Malta Review 2016 Page 1 of 299 pages Malta Country Overview MALTA Malta is an island nation state located in the Mediterranean Sea to the south of the Italian island of Sicily -- between Europe and North Africa. -

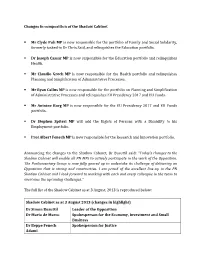

Changes in Composition of the Shadow Cabinet Mr Clyde Puli MP

Changes in composition of the Shadow Cabinet . Mr Clyde Puli MP is now responsible for the portfolio of Family and Social Solidarity, formerly tasked to Dr Chris Said, and relinquishes the Education portfolio. Dr Joseph Cassar MP is now responsible for the Education portfolio and relinquishes Health. Mr Claudio Grech MP is now responsible for the Health portfolio and relinquishes Planning and Simplification of Administrative Processes. Mr Ryan Callus MP is now responsible for the portfolio on Planning and Simplification of Administrative Processes and relinquishes EU Presidency 2017 and EU Funds. Mr Antoine Borg MP is now responsible for the EU Presidency 2017 and EU Funds portfolio. Dr Stephen Spiteri MP will add the Rights of Persons with a Disability to his Employment portfolio. Prof Albert Fenech MP is now responsible for the Research and Innovation portfolio. Announcing the changes to the Shadow Cabinet, Dr Busuttil said: “Today’s changes to the Shadow Cabinet will enable all PN MPs to actively participate in the work of the Opposition. The Parliamentary Group is now fully geared up to undertake its challenge of delivering an Opposition that is strong and constructive. I am proud of the excellent line-up in the PN Shadow Cabinet and I look forward to working with each and every colleague in the team to overcome the upcoming challenges.” The full list of the Shadow Cabinet as at 3 August, 2013 is reproduced below: Shadow Cabinet as at 3 August 2013 (changes in highlight) Dr Simon Busuttil Leader of the Opposition Dr Mario de Marco -

Parliament Report

House of Representatives Annual Review 2006 THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES THE PALACE VALLETTA – MALTA TEL : +356 2559 6000 FAX : +356 2559 6400 WEBSITE: www.parliament.gov.mt Printed at the Government Press CONTENTS Foreward i (A) HOUSE BUSINESS 6 (1) Overview 6 (2) Legislative Programme 7 (3) Parliamentary Questions 10 (4) Ministerial Statements 10 (5) Petitions 10 (6) Motions 11 (7) Papers laid 11 (8) Divisions 11 (B) STANDING COMMITTEES 11 (1) Standing Committee on House Business 13 (2) Standing Committee on Privileges 14 (3) Standing Committee on Public Accounts 14 (4) Standing Committee on Social Affairs 15 (5) Standing Committee on Foreign and European Affairs 17 (6) Standing Committee for the Consideration of Bills 19 (7) Standing Committee on Development Planning 19 (8) National Audit Office Accounts Committee 19 (C) INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITIES 20 (1) Mr Speaker 20 (2) Deputy Speaker 22 (3) Conferences hosted by the House of Representatives 22 (4) Outgoing visits of Maltese parliamentary delegations 22 (5) Incoming visits of parliamentary delegations 28 (6) Parliamentary Friendship Groups 28 (D) ASSOCIATION OF FORMER MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENTS 28 (E) OTHER ACTIVITIES 28 (F) OBITUARIES 31 ANNEXES A. Members of Parliament – 10th Legislature 33 B. Schedule of Meetings of Hon Speaker of the House of Representatives 34 C. Extract from the Standing Orders re Standing Committees 37 D. Meetings of the Standing Committee on House Business 42 E. Meetings of the Standing Committee on Public Accounts 43 F. Meetings of the Standing Committee for Social Affairs 44 G. Meetings of the Standing Committee on Foreign and European Affairs 46 H. -

Newsletter 30

If you need to print this newsletter, please use both sides of recycled paper Contents: • Editorial Note • HSBC-ES Climate Initiative • EkoSkola’s contribution to Eco-Gozo • Kikku the bee • The Moving Drop • Fun run for trees • Activities from our schools July 20 20111111 • Teaching Resources Issue 303030 • YRE Newsletter No. 2 Editorial Note Another scholastic year is through and most of the initiatives that you have been working on have been completed. In this edition of our newsletter we are presenting some of these initiatives and achievements. We believe that sharing such initiatives has two important outcomes: promoting schools’ achievements and sharing good practice. January 20 th , 2011 was a special day for our EkoSkola teachers. It marked the presentation of their degree certificate by the Italian Ambassador, His Excellency E. Luigi Marras. The ceremony marked the crowning moment of an intensive professional master in Intercultural Eco- Management of Schools developed by the University Cà Foscari, Venice. HSBC-ES Climate Initiative Left: The EkoSkola teachers presenting the Green Flag during the thanksgiving mass. Right: The EkoSkola team in a photo line-up after the ceremony! The following were the research projects they presented for the masters: • A Strategic Intercultural and Environmental Management Plan for a Girls’ Secondary School: A potential approach to meet sustainable development challenges by Ms Cynthia Caruana; • A Sustainability Reporting Tool for Schools Leading Maltese Schools towards Sustainability by Ms Audrey Gauci and Ms Marvic Refalo; and Nature Trust (Malta) EkoSkolaEkoSkola Network Network Newsletter Newsletter EkoSkolaEkoSkola Network Network Newsletter Newsletter PO Box 9 Valletta VLT1000 http://www.naturetrustmalta.org / • ‘Walking the talk’ - A Sustainable Mobility Plan for two state owned schools in Paola by Mr Johann Gatt and Ms Elizabeth Saliba. -

The Offices of the President and the Prime Minister of Malta: a Way Forward, and the Work Presented in It, Is My Own

The Offices of the President and the Prime Minister of Malta: A Way Forward Luke Dalli A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Laws, University of Malta, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) Faculty of Laws University of Malta May 2013 University of Malta Library – Electronic Theses & Dissertations (ETD) Repository The copyright of this thesis/dissertation belongs to the author. The author’s rights in respect of this work are as defined by the Copyright Act (Chapter 415) of the Laws of Malta or as modified by any successive legislation. Users may access this full-text thesis/dissertation and can make use of the information contained in accordance with the Copyright Act provided that the author must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the prior permission of the copyright holder. DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Luke Dalli, declare that this thesis entitled The Offices of the President and the Prime Minister of Malta: A Way Forward, and the work presented in it, is my own. I confirm that: The Word Count of the thesis is 35,000. This work was done in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Laws at the Faculty of Laws of the University of Malta. Where any part of this thesis has previously been submitted for a degree or any other qualifications at this University or any other institution, this has been clearly stated. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. -

Thenewfederalist

MAGAZINE OF THE YOUNG EUROPEAN FEDERALISTS ISSUE 2/2006 thenewfederalist new series VOX POPULIS E-GOVERNANCE PETITION DEMOCRACY ELECTIONS POLITICAL BLOGGING PARTICIPATION WHAT’S IN HERE? contents 03 dear reader daniela grech 04 constitution? straight to the emergency room! jan seifert EVOLVING EUROPE 05 europe and the sauna george kipouros 06 a european in the italian parliament daniela grech 09 change in italy and a visit to ventotene federico brunelli 10 a hope for democracy in belarus vaida jazepcikaite 11 hungarian parliamentary (s)elections daniel bartha 12 what caused the turmoil in france fabien cazenave & damien routisseau 13 the plight of polish workers in ireland elizabeth lannoo 14 europe and asylum: a promise betrayed jean pierre gautci EVOLVING REACHING EUROPE 15 e-governance for eu democracy asimakis valavanis 16 do eu blog? jon worth 17 the next generation anne-christine roisin 18 european civil service - a wonderful project jessica pennet REACHING THINKING FEDERALIST 19 vox populis radostina zhelyazkova 21 second citizens' convention in vienna friedhelm frischenschlager & reinout prez 22 european parliament, quo vadis? emmanuel vallens & anders ekberg 24 the services directive: take it or leave it lieven tack FEDERALIST ACTIVE JEF 25 the jef europe foundation thomas heissmeier 26 two stars make a supernova ecaterina matcov 27 life in jef sections vaida jazepcikaite 28 contact ACTIVE JEF WHAT’S THIS? WHO MADE THIS? WHO PAYS? thenewfederalist editorialboard financing The New Federalist is a publication of the Daniela Grech, Editor in Chief JEF-Europe receives financial support Young European Federalists (JEF-Euro- Samuel Müller, Layout Editor from the European Commission and the pe).