Socialsoccer the Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small-Sided Football Laws of the Game

SMALL-SIDED FOOTBALL 2016-2017 451 SMALL-SIDED FOOTBALL LAWS OF THE GAME Revised February 2012 Introduction The following laws of the game are The Football Association’s recommended laws for use in Small- Sided Football. This includes 5, 6 and 7-a-side games but not Mini-Soccer or Futsal, which have their own specific laws. (These are also available from The FA). These Laws were revised in 2012 based on the following principles; • A revision of The FA’s Laws so that they better reflect the game that it is being played in many venues • Applying the general principle of the ‘normal laws of Association Football with exceptions’ and as consequence simplifying the game for both players and referees. • Improving the technical quality of play in the small-sided game • To encourage participation and enjoyment in a safe and controlled environment. Over 1.05 million adults play Small Sided Football every week in over 22000 organised Small Sided Football teams (Sport England Active People Survey 2015). As a consequence Small Sided Football is now the largest form of the recreational game. The laws that people play the game tend to differ from venue to venue and reflect both traditions of play and the constraints of the facility in which the game is taking place. The set of Laws contained in this document are those that the FA will use in its own Small Sided Football competitions and we would recommend their adoption by all organisers of Small Sided Football. However given the diversity of small sided facilities and formats in this country use of these Laws in all circumstances is not mandatory and these revised Laws also allow the FA and the County Football Associations to sanction other formats of Small Sided Football. -

Raaa In-House Soccer Rules of the Game for 4 – 5 Grades

RAAA IN-HOUSE SOCCER RULES OF THE GAME FOR 4TH – 5TH GRADES Administrative Laws 7. Duration of the Game 12. Fouls and Misconduct 8. Start of Play 13. Free Kick (Direct or 1. Field of Play 9. Ball in and out of Play In-Direct) 2. Ball 14. Throw-In 3. Numbers of Players Game Laws 15. Goal Kick 4. Players’ Equipment 16. Corner Kick 5. Referees 10. Method of Scoring 6. Linesman 11. Off-Side Diagram of the soccer field: RAAA In-House Soccer Coach/Parent Handbook Page 1 of 7 Law 1: Field of Play The field size is determined by the Field Director based on the available space at the location. Coaches have the right to postpone a game due to the current weather or state of the playing field by mutual agreement prior to the game. Both teams must report to the playing field by mutual agreement prior to the game to make a determination unless the situation is obvious. Rain is not necessarily a reason to postpone a soccer game, however, thunder and lightning are. RAAA will make weather related decisions to cancel soccer by 4 PM on game days and will post on the RAAA website. Please make sure to check the website if in doubt about the weather. Games will be cancelled for heat indices over 100 degrees. Once the game has started, the referee is in complete charge of the game and the referee is the sole judge as to the suitability of the field of play. If the game is postponed for any reason, the coaches have the responsibility to notify the Referee Director of the postponement and the new game time. -

Futsal Rules

FUTSAL RULES 1) The Court and Ball a) Games will be played in the Sports Hall at UniRec. b) The boundaries will consist of; white lines (sidelines), red lines (goal lines) and the purple half circle (goalkeepers area). c) Regulation size 4 futsal balls will be used. d) All court boundaries and dimensions will be demonstrated for teams if necessary. e) Only music from the UniRec sounds system can be played during the Social Sport competition 2) The Number of Players a) Teams may have a maximum of 10 players per team; 5 players are on the court at one time, 4 court players and 1 goalkeeper. There must be at least one player of each gender on court at all times. b) There are unlimited substitutions. c) The referee must be notified if the goalkeeper is changed. 3) The Player’s Equipment a) All players within a team must wear the same colour playing shirt. Uniforms are highly encouraged, but a coordinated colour will suffice. b) All players must wear non-marking, athletic footwear. c) Shin pads are highly recommended. d) Players may not wear jewellery, any other sharp adornments or anything that may be deemed dangerous to other players. 4) The Duration of the Match a) The games will be 2 x 20 minute halves with a 2 minute break for half time. 5) The Start and Restart of Play a) From a kick off, the ball can travel in any direction. A goal cannot be scored directly from a kick off. b) The opposing team must be inside their own half, at least 3m away. -

IFAB Laws of the Game Changes 2019/2020

IFAB Laws of the Game Changes 2019/2020 WRITTEN BY IFAB The following summarizes the main Law changes for 2019/20: Substitutes - Law 3 [The Players] Changes A player who is being substituted must leave the field by the nearest point on the touchline/goal line (unless the referee indicates the player can leave quickly/immediately at the halfway line or a different point because of safety, injury etc.). Players' Equipment - Law 4 [The Players’ Equipment] Changes Multi-colored/patterned undershirts are allowed if they are the same as the sleeve of the main shirt. Team Officials - Laws 5 [The Referee] & 12 [Fouls and Misconduct] Changes A team official guilty of misconduct will be shown a YC (caution)* or RC (sending-off)*; if the offender cannot be identified, the senior coach who is in the technical area at the time will receive the YC/RC*. Law 12 will have a list of YC/RC offences. Medical Breaks - Law 7 [The Duration of the Match] Changes Difference between ‘cooling’ breaks (90 seconds – 3 minutes) and ‘drinks’ breaks (max 1 minute). Kick-Off - Law 8 [The Start and Restart of Play] Changes The team that wins the toss can now choose to take the kick-off or which goal to attack (previously they only had the choice of which goal to attack). Dropped ball - Laws 8 [The Start and Restart of Play] & 9 [The Ball in and out of Play] Changes If play is stopped inside the penalty area, the ball will be dropped for the goalkeeper. If play is stopped outside the penalty area, the ball will be dropped for one player of the team that last touched the ball at the point of the last touch. -

2021 Modified Rules Overview - FDLSA Rec League

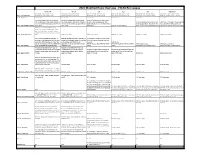

2021 Modified Rules Overview - FDLSA Rec League U4/U5 / U6 U7 / U8 U10 U12 U14 High School Minimum (L x W): 20 yds x 15 yds Minimum (L x W): 25 yds x 20 yds Minimum (L x W): 45 yds x 35 yds Minimum (L x W): 70 yds x 45 yds Minimum (L x W): 100 yds x 50 yds Minimum (L x W): 100 yds x 50 yds Law 1 - The Field of Play Maximum (L x W): 30 yds x 25 yds Maximum (L x W): 35 yds x 30 yds Maximum (L x W): 60 yds x 45 yds Maximum (L x W): 80 yds x 55 yds Maximum (L x W): 130 yds x 100 yds Maximum (L x W): 130 yds x 100 yds Law 2 - The Ball Size three (3) Size three (3) Size four (4) Size four (4) Size five (5) Size five (5) Games will be played with four players per Games will be played with four players per Games will be played with seven players side. No goalkeepers. Each player shall play a side. No goalkeepers. Each player shall play a per side, including a goalkeeper. Each Games will be played with eleven players, SAME AS U14. Two girls on the playing field minimum of 50% of total playing time. Pinnie minimum of 50% of total playing time. Pinnie player shall play a minimum of 50% of total including a goalkeeper. Each player shall should be present. If playing down, the Law 3 - The Number of Players Rule in Place. -

United States Soccer Federation Advice To

UNITED STATES SOCCER FEDERATION ADVICE TO REFEREES ON THE LAWS OF THE GAME UNITED STATES SOCCER FEDERATION ADVICE TO REFEREES ON THE LAWS OF THE GAME Acknowledgments The United States Soccer Federation’s National Referee Development Program is very pleased to acknowledge the work of the instructors who contributed to this tenth, updated edition of the Advice to Referees on the Laws of the Game. The principal authors of the publication were Jim Allen, who doubled as editor, and Dan Heldman. Substantial contributions to this updated edition came from Gil Weber, Ulrich Strom, Wally Beaumont, Michelle Maloney, Tom Frazee, and Randall Reyes (who also does the translation for the Spanish version of the Advice). Many of the additions and changes came about as the result of questions or suggestions from referees, players and coaches across the country. Alfred Kleinaitis Manager of Referee Development and Education July 2010 Advice to Referees on the Laws of the Game Revised 2010 United States Soccer Federation, Inc. 1801 S. Prairie Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 Telephone: 312/808-1300 Fax: 312/808-1301 http://www.ussoccer.com Copyright 2010 United States Soccer Federation, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the United States Soccer Federation, Inc. Table of Contents Acknowledgments Table of Contents Advice to Referees Law 1 - The Field of Play Law 2 - The Ball Law 3 - The Number of Players Law 4 - The Players’ Equipment Law 5 - The Referee Law 6 - The Assistant Referee and Fourth Official Law 7 - The Duration of the Match Law 8 - The Start and Restart of Play Law 9 - The Ball In and Out of Play Law 10 - The Method of Scoring Law 11 - Offside Law 12 - Fouls and Misconduct Part A. -

Boys & Girls 5/6 Division Rules.Pdf

5/6 Year Olds 7 v 7 Rules Specifics Amended Laws Field Size N/A Goal Area N/A Penalty Spot N/A Penalty Area N/A Ball Size 3 Goal Size 4ft x 6ft Game Length 32 Minutes: 4 x 8 Minute Quarters Between Quarters 5 minutes Substitutions Whenever when play is stopped. Ie: throw in, free kick, after a goal Players In Positions None Goalkeeper Yes Contact (ex. Yes, so long as they abide by the fair tackle ruling tackles) Kick Off On center spot, opposition outside the circle Throw Ins 2 feet on ground with arms behind head Fouls, Misconduct indirect free kick, always explain call, 5 yards clear Goal Kick Goalkeeper will kick the ball from the edge of the penalty box Corner Kick As per Usual Offside none Pass backs not applicable Coaching Never on field during play, does substitutions 6 goals max, coaches should ensure they are doing everything Mercy Rule possible to prevent running up a high score 1. FIELD OF PLAY Restarts Cause Kick Off Start game, start of quarters, after scores Out of bounds on sidelines by defense, 2 feet on ground with arms Throw In behind head redo as needed, 2 yds clear Indirect Free Kick Fouls, misconduct redo as needed, 5 yds clear Goal Kick Out of bounds by offense over goal line Edge of penalty area, redo as needed, 5 yds clear Drop Ball Circumstances not covered above redo as needed 2. BALL SIZE Size 3 3. NUMBER OF PLAYERS Two teams of 7 players. Coaches may play 6 players. -

U10 YMCA of NWNC Outdoor Soccer Rules

U10 YMCA of NWNC Outdoor Soccer Rules Law 1 – The Field of Play Dimensions: The field of play must be rectangular. The length of the touchline must be greater than the length of the goal line. Length (yards): 60 Width (yards): 40 Field Markings: Distinctive lines not more than (5) inches wide. The field of play is divided into two halves by a halfway line. The center mark is indicated at the midpoint of the halfway line. A circle with a radius of four (8) yards is marked around it. The Goal Area: 5 yards deep by 16 yards wide The Penalty Area: 10 yards deep by 26 yards wide Goals: 6’6”x12’ Law 2 – The Ball Size four (4) Law 3 – The Number of Players A match is played by two teams, each consisting of not more than 6 players. There will be a goalkeeper (included in the total number). Substitutions: At any stoppage of play and unlimited. Sub must be called in by the official. Playing time: Each player SHALL play a minimum of 50% of the total playing time. Teams and matches may be coed. MAXIMUM ROSTER SIZE: 12 Law 4 – The Players’ Equipment Players shall wear a YMCA provided uniform. Players must also wear shin guards. Cleats are recommended. Non- uniform clothing is allowed based on weather conditions, but uniforms must still distinguish teams. Law 5 – The Referee An OFFICIAL will be used. All infringements shall be briefly explained to the offending player. Law 6 – The Assistant Referees No Assistant Referee will be used for U10 matches. -

A Soccer Guide for Parents

A Soccer Guide For Parents A Soccer Guide for Parents Used with permission from the Florence Soccer Association Table of Contents Why this booklet? __________________________________ 3 A Brief History of the Game _________________________ 3 Suggestions for Parents _____________________________ 3 The Laws of the Game -- A Simplified Explanation ______ 6 Law 1 - The Field of Play _________________________________ Law 2 - The Ball ________________________________________ Law 3 - The Number of Players ____________________________ Law 4 - Players Equipment ________________________________ Law 5 - Referees ________________________________________ Law 6 - The Assistant Referees_____________________________ Law 7 - The Duration of the Match__________________________ Law 8 - The Start and Restart of Play ________________________ Law 9 - The Ball In and Out of Play _________________________ Law 10 - The Method of Scoring ___________________________ Law 11 - Offside ________________________________________ Law 12 - Fouls and Misconduct ____________________________ Law 13 - Free Kicks _____________________________________ Law 14 - The Penalty Kick ________________________________ Law 15 - The Throw-In ___________________________________ Law 16 - The Goal Kick __________________________________ Law 17 - The Corner Kick_________________________________ A Note about Fouls ________________________________ 12 Glossary of soccer terms____________________________ 13 More on Offside __________________________________ 16 Where to find out more... _____ Error! -

Laws of the Game Goalkeeper

Law 3 – Number of Players – 7v7– one of those being a Laws of the Game goalkeeper. The number of players provides the opportunity for the children to further develop their physical and technical abilities and WSA/CSC modifications of the Laws of the Game requires the players to make more decisions and experience for 10U – 7v7 Soccer Games repeating game situations more frequently. Substitutions: At any stoppage of play and unlimited. When subbing a player, have them stand off the field about 1 yard at the center line for the referee to call them into the game. Playing time: Every effort shall be made for each player to play a minimum of 50% of the game. Law 4 – Player Equipment – • team jersey and athlete shorts or sweats– • Shin-guards are MANDATORY, socks covering the shin-guards • Footwear – Tennis shoes or Soccer cleats- no toe cleat – cleats are recommended Law 5 and 6 – Referee – 1 center referee, the center will call offside to the best of his ability. Law 1 – Field of play is rectangular. ** The dimensions are smaller to accommodate the 7v7 game and appropriate for the movement Law 7 - Duration of the game - 2 – 25 minute halves with capabilities of children 10 and younger. approximately a 5 min half time. Field markings – Distinctive outline of the field with a halfway line across the field. The center circle gives the players a concert marking Law 8 – Start or restart of a game - per FIFA - Players line up on their on where to be for kick-off. The penalty area and goal area are defending half of the field. -

Futsal Rules

FUTSAL RULES Each player is responsible for presenting a current UNC ONE CARD or valid government ID at game time. NUMBER OF PLAYERS Number of Players to Start Match: 4 to 5, one of whom shall be a goalkeeper Number of Players to Default Match: 3 Number of Players to Forfeit Match: 0 to 2 Substitution Method: "Flying substitution" (all players but the goalkeeper enter and leave as they please; goalkeeper substitutions can only be made when the ball is out of play and with a referee's consent) PLAYERS' EQUIPMENT Usual Equipment: Numbered shirts, shorts, socks, protective shin-guards and footwear with rubber soles DURATION OF THE GAME Duration: Two equal periods of 16 minutes; running clock. Time-outs: 1 per team per half; none in extra time Half-time: 3 minutes Mercy Rule: If a team is ahead by 7 or more points at 3 minutes or goes ahead by 7 or more points under 3 minutes in the second half, the game will be ended at that point. THE START OF PLAY Procedure: Rock, paper, scissors followed by kickoff; opposing team waits outside center circle; ball deemed in play once it has been touched; the kicker shall not touch ball before someone else touches it; ensuing kick-offs taken after goals scored and at start of second half. BALL IN AND OUT OF PLAY Ball out of play: When it has wholly crossed the goal line or touchline; when the game has been stopped by a referee; when the ball hits the ceiling (restart: kick-in at the place closest to where the ball touched the ceiling). -

Football Rules, Protocol and Etiquette

FOOTBALL COACHING GUIDE Football Rules, Protocol & Etiquette Football Rules, Protocol & Etiquette Table of Contents Table of Contents Teaching Football Rules Unified Sports Rules Protest Procedures Sportsmanship Football Glossary 2 Special Olympics Football Coaching Guide Created: February 2004 Football Rules, Protocol & Etiquette The Rules of Football Teaching the Rules of Football The best time to teach the rules of football is during practice. Please refer to the Official Special Olympics Sports Rules Book for the complete listing of football rules. The International Federation of Football Association’s (FIFA) Fair Play Philosophy is advocated throughout the football world. The following guidelines are taken from FIFA’s Laws of the Game and Universal Guide for Referees. As coach, it is your responsibility to know and understand the rules of the game. It is equally important to teach your players the rules and to make them play within the spirit of the game. Below are selected laws of the 17 laws that govern the game of football. Maintain current copies of the Special Olympics Sports Rules and your national and international federation football rulebooks. Know the differences and carry them to every game. Law V - Referees The referee is responsible for the entire game, including keeping a record of the game and acting as the timekeeper. The referee makes decisions on penalties, cautions and ejects players for misconduct. The referee may also end the game due to inclement weather, spectator interference, etc. Referee determines injury time outs and other time stoppages. All decisions by the referee are final. Law VI - Linesmen Two linesmen are primarily responsible for indicating to the referee when the ball is out of play and which team is entitled to a throw-in, goal kick or corner kick.