Rethinking the Reporting of the Mass Random Shooting – Or Is It an Autogenic Massacre?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Ways of Seeing': the Tasmanian Landscape in Literature

THE TERRITORY OF TRUTH and ‘WAYS OF SEEING’: THE TASMANIAN LANDSCAPE IN LITERATURE ANNA DONALD (19449666) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (English and Cultural Studies) 2013 ii iii ABSTRACT The Territory of Truth examines the ‘need for place’ in humans and the roads by which people travel to find or construct that place, suggesting also what may happen to those who do not find a ‘place’. The novel shares a concern with the function of landscape and place in relation to concepts of identity and belonging: it considers the forces at work upon an individual when they move through differing landscapes and what it might be about those landscapes which attracts or repels. The novel explores interior feelings such as loss, loneliness, and fulfilment, and the ways in which identity is derived from personal, especially familial, relationships Set in Tasmania and Britain, the novel is narrated as a ‘voice play’ in which each character speaks from their ‘way of seeing’, their ‘truth’. This form of narrative was chosen because of the way stories, often those told to us, find a place in our memory: being part of the oral narrative of family, they affect our sense of self and our identity. The Territory of Truth suggests that identity is linked to a sense of self- worth and a belief that one ‘fits’ in to society. The characters demonstrate the ‘four ways of seeing’ as discussed in the exegesis. ‘“Ways of Seeing”: The Tasmanian Landscape in Literature’ considers the way humans identify with ‘place’, drawing on the ideas and theories of critics and commentators such as Edward Relph, Yi-fu Tuan, Roslynn Haynes, Richard Rossiter, Bruce Bennett, and Graham Huggan. -

Knight V Commonwealth of Australia (No 3)

SUPREME COURT OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Case Title: Knight v Commonwealth of Australia (No 3) Citation: [2017] ACTSC 3 Hearing Dates: 4, 7 May, 3 August, 3 November 2015 Decision Date: 13 January 2017 Before: Mossop AsJ Decision: See [233] Catchwords: LIMITATION OF ACTIONS – Application for extension of time – Claim for damages arising out of assault and negligence – Multiple incidents giving rise to claims – Incidents occurred while plaintiff was a cadet at the Royal Military College, Duntroon – Plaintiff subsequently sentenced and imprisoned for separate incident – 27-year delay in commencing proceedings – Whether Limitation Act 1985 (ACT) s 36 permitting the grant of an extension of time applies – Whether an explanation for the delay existed – Whether just and reasonable to grant extension of time – Consideration s 36(3) considerations – Meaning of disability for the purposes of s 36(3)(d) – Broader significance in relation to abuse in the armed services – Significance of absence of other remedies – Proportionality between damages and cost and effort associated with running claim – Whether proceedings amount to abuse of process – Whether use of proceedings as a means of achieving an interstate transfer predominant purpose of bringing proceedings – application dismissed Legislation Cited: Civil Law (Wrongs) Amendment 2003 (No 2) (ACT), s 58 Corrections Act 1986 (Vic), s 74AA Corrections Amendment (Parole) Act 2014 (Vic) Crimes (Sentence Administration) Act 2005 (ACT), s 244 Interpretation of Legislation Act 1984 (Vic) Legislation -

Smiling Assassin Gets Life

ntnews.com.aulllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll NATION ABBOTT TO AXE JOBS CANBERRA: Federal Opposit- ion Leader Tony Abbott yesterday indicated public servant job cuts under a Coalition government may Smiling be even larger than the 12,000 previously targeted, sparking an angry response from unions and disbelief from the government. FLOODWATERS PEAK assassin MELBOURNE: Residents in the flood-besieged Victorian town of Nathalia are increas- ingly confident they can beat the wall of water threaten- ing them, with flooding de- clared to have peaked. About gets life 90 per cent of the town’s 1400 residents have stayed to defend their properties. By AMY DALE — but after ‘‘observing her’’ for some time, he was forced RINEHART LOSES BID SYDNEY: Former US Marine to abandon this plan. SYDNEY: The High Court has Walter Marsh stared past the The 51-year-old then went knocked back Gina Rinehart’s relieved cheers of Michelle on to murder his former boss bid to challenge orders al- Beets’ family and friends yes- in a ‘‘brutal attack’’. lowing her family trust battle terday to greet with a smile In sentencing him yester- to be made public. The court the news that he will spend day, Justice Derek Price yesterday refused to grant the rest of his life in jail. described the murder of Ms Australia’s richest person But behind the grin yester- Beets as ‘‘cruel, merciless leave to appeal against a de- day was the startling revel- and abhorrent’’. cision revoking suppression ation of just how close he The emergency nursing orders made in the NSW came to allegedly murdering unit manager at Sydney’s Supreme Court legal dispute. -

Impact of News Reporting on Victims and Survivors of Traumatic Events

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Online Asia Pacific Media ducatE or Issue 7 Article 4 7-1999 Fair game or fair go? Impact of news reporting on victims and survivors of traumatic events T. McLellan Queensland University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/apme Recommended Citation McLellan, T., Fair game or fair go? Impact of news reporting on victims and survivors of traumatic events, Asia Pacific Media ducatE or, 7, 1999, 53-73. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/apme/vol1/iss7/4 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] TRINA McLELLAN: Fair game or fair go? ... Fair Game Or Fair Go? Impact Of News Reporting On Victims And Survivors Of Traumatic Events When traumatic incidents occur, victims and survivors – as well as their families, friends and immediate communities – respond in varying ways. Over the past century, however, researchers have mapped common psychosocial consequences for victims/survivors in their studies of what has come to be known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Over the same period, journalists and news media managers have adopted local, medium-specific and industry-wide journalistic standards for acceptable ethical and operational behaviours when it comes to covering such incidents. Yet, despite numerous prescriptive codes – and growing public criticism – Australia’s news media continues to confront victims/ survivors in large numbers when they are at their most vulnerable... and sometimes in ways that are, at best, questionable. -

Caged Untold

Contents ENTER THE OCTOGON: D- DIVISION YARDS, FIRST SKIRMISH/FIRST BLOOD. Firstly don�t pre-warn your enemies of your intentions. THE CHOOK PEN: THE PORTABLES OCTOGON, BLINDSHOT: BANG RIGHT BETWEEN THE EYES! FRANK WAGHORN BOILED BEECHWORTH VIOLENCE. B.B.Q. PAEDAPHILE FIZZLED! GEELONG JAIL �RAMBO �PILLED UP� GEELONG JAIL WAS MINE FOR AN HOUR ARARAT JAIL, OUTBOXED! BEANS BY ALL MEANZ! MY BEST FIGHT EVER! Raw, ferocious, blood, sweat and stiches! AT WAR WITH CHOPPER B �DIVISION PENTRIDGE 1990; THE OCTOGON! PAYROLL ICE PICKED! BANG ON CUE! UNLUCKY FOR SOME, PICK OF THE HAT! JULIAN KNIGHT, BANG. LIGHTS OUT NIGHT! Not a word was uttered from him at all. PETER GIBB: I did make an impression on him. KUNG-FOOL LEWIS CAINE. TUNNEL VISION, PATRICK MILLS, BECOMES AIR BORNE! LEGAL VISIT TERMINATED, WASN�T ME! TED EASTMOND MERRY X-MAS TED! TED DEMANDS ME CHARGED HE IS PISSED! DHJANGO: LETS PLAY! SPLIT DECISION! RUNNERS LENT, I WOULD FIGHT FOR. CHEAP SHOT! SMOKE SIGNALS! POT PREDATORS! EXAMPLES MADE, JUST BUSINESS! SPEARED, KOORI PUNISHMENT! HALF TIME HUDDLE! COMPLY OR BE GASSED! GOULBURN YARDS, DEADLY TERRAIN! Attack on sight were orders from every yard! CANTEEN UP! WEAPONS ORDERED! SUNDAYS LOCK N LOAD, NO CHURCH SERVICE! LOCKED IN THE OCTOGON LIVE BAIT! ROCKING TO GHOST TUNES.COMBAT MODE! DUDS, FIZZLED THREATS BUNKER CONTROLLED ATTACK! HUMAN CURTAIN DRAWN OUT COLD! NOT ALL HAPPY FATWAH ME VS THE LEB YARD SOLO! ALL IN RECON COMES UNDONE! GOULBURN RIOT KICKS OFF! CAGE FIGHTING IN TRANSIT NO REFS! C- CLASSO BUS RIDE CANCELLED, ONBOARD CONTRABAND FOUND. STEPPO; ARMED TO PLAY NINJA TURTLE SEX OFFENDERS were NOT welcome! SNAKE PIT! GAVIN PRESTON: GAVS VERBAL CANT FIGHT! PASQUALE BARBARO. -

THE QUEEN V. MARTIN BRYANT

Page 50. IN THE CRIMINAL SITTINGS OF THE SUPREME COURT HELD AT NUMBER 7 COURT, SALAMANCA PLACE, HOBART, BEFORE HIS HONOUR THE CHIEF JUSTICE, ON TUESDAY THE 19TH DAY OF NOVEMBER, 1996 THE QUEEN v. MARTIN BRYANT Appearances: MR. D. BUGG Q.C. and MR. N. PERKS for the Crown MR. J. AVERY for the Accused MR. BUGG Q.C. (Stating facts): Your Honour, Martin Bryant has pleaded guilty to all counts in the indictment which was filed in this Court on the 5th of July. On the 28th of April of this year he travelled to Port Arthur. He drove there in his Volvo sedan which at the time had a surfboard placed on the roof racks on top of the car. The Crown’s case is that at the outset of that journey he intended at least some form of violent confrontation with Mr. And Mrs. Martin of the Seascape tourist accommodation facility at Port Arthur and in all probability his intentions also extended to actions which had the devastating impact on the community and the people of Port Arthur on that day. Page 51. I say this because on the Crown case he had made preparations which were inconsistent with his normal behaviour. He behaved deceptively to those close to him, as to his possession and use of firearms. They were concealed in his house in the body of two pianos and elsewhere within the house out of view of visitors to that property. Yet, when he left the property on the morning of the 28th of April to travel to Port Arthur he left one semi-automatic firearm and a substantial quantity of ammunition in the hallway of the house. -

The Question of “Why?” People Become Lone-‐ Gunmen

TILBURG UNIVERSITY The Question of “Why?” People Become Lone- Gunmen A Literary Research on the Motivation of Lone- Gunmen M. Guijt 25/06/2014 Supervisors: prof. dr. S. Bogaerts, prof. dr. J. Denissen 1. Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents 2 2. Abstract 3 3. Introduction (+ research questions) 4 4. Method 6 5. Martin Bryant 7 5.1. The Situation 8 5.2. The Criminal Proceedings 11 5.3. The Study of a Person 14 5.4. The Suspected Motivation 20 6. Anders Behring Breivik 23 6.1. The Situation 23 6.2. The Criminal Proceedings 27 6.3. The Study of a Person 28 6.4. The Suspected Motivation 32 7. James Eagan Holmes 34 7.1. The Situation 34 7.2. The Criminal Proceedings 35 7.3. The Study of a Person 36 7.4. The Suspected Motivation 37 8. Discussion 38 8.1. How are these cases alike? 38 8.2. How are these cases different? 40 8.3. What could be the motivation? 41 1 | Lone- Gunmen Bachelor Thesis M. Guijt 8.4. What are predictors? 42 9. Conclusion 43 10. References 46 11. Appendix 1: Remembering the Victims 53 2 | Lone- Gunmen Bachelor Thesis M. Guijt 2. Abstract In 1996, 2011, and 2012, three atrocities have been committed that ended in the combined deaths of 124 people and the injuring of 412 people. These three separate killings were all committed by what is known as “lone-gunmen”. These lone-gunmen typically go into a – seemingly randomly selected – public place, pull out a gun or multiple guns, and start shooting. -

Postmaster & the Merton Record 2017

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2017 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Features Records Edited by Merton in Numbers ...............................................................................4 A long road to a busy year ..............................................................60 The Warden & Fellows 2016-17 .....................................................108 Claire Spence-Parsons, Duncan Barker, The College year in photos Dr Vic James (1992) reflects on her most productive year yet Bethany Pedder and Philippa Logan. Elections, Honours & Appointments ..............................................111 From the Warden ..................................................................................6 Mertonians in… Media ........................................................................64 Six Merton alumni reflect on their careers in the media New Students 2016 ............................................................................ 113 Front cover image Flemish astrolabe in the Upper Library. JCR News .................................................................................................8 Merton Cities: Singapore ...................................................................72 Undergraduate Leavers 2017 ............................................................ 115 Photograph by Claire Spence-Parsons. With MCR News .............................................................................................10 Kenneth Tan (1986) on his -

Active Shooter: Recommendations and Analysis for Risk Mitigation

. James P. O’Neill . Police Commissioner . John J. Miller . Deputy Commissioner of . Intelligence and . Counterterrorism ACTIVE SHOOTER James R. Waters RECOMMENDATIONS AND ANALYSIS Chief of Counterterrorism FOR RISK MITIGATION 2016 EDITION AS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................3 RECENT TRENDS ........................................................................................................................6 TRAINING & AWARENESS CHALLENGE RESPONSE .................................................................................... 6 THE TARGETING OF LAW ENFORCEMENT & MILITARY PERSONNEL: IMPLICATIONS FOR PRIVATE SECURITY ........ 7 ATTACKERS INSPIRED BY A RANGE OF IDEOLOGIES PROMOTING VIOLENCE ................................................... 8 SOCIAL MEDIA PROVIDES POTENTIAL INDICATORS, SUPPORTS RESPONSE .................................................... 9 THE POPULARITY OF HANDGUNS, RIFLES, AND BODY ARMOR NECESSITATES SPECIALIZED TRAINING .............. 10 BARRICADE AND HOSTAGE-TAKING REMAIN RARE OCCURRENCES IN ACTIVE SHOOTER EVENTS .................... 10 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................11 POLICY ......................................................................................................................................... -

Fall 2018.Pdf

THE UNDERGRADUATE POLITICAL REVIEW FALL 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT “Volatile Political and Institutional Change: Discourses on our Future” Contributors The Editorial Board Austin Beaudoin, Editor-in-Chief Kyle Adams, Assistant Editor-in-Chief Marianna Kalander, Assistant Editor Shankara Narayanan, Assistant Editor Andrew Spearing, Assistant Editor Advising Professor Oksan Bayulgen, PhD. Contents: Letter from the Editor Austin Beaudoin Sections: Shifting Power Structures and International Disputes A Return to Bipolarity and the Erosion of International Law Austin Beaudoin Isolationist Foreign Policy and the Liberal World Order Emily Coletta Addressing Climate Change Amidst the Rise of Populism Elizabeth Jennerwein Shifting Sands: America, Iran, and the New Middle East Shankara Narayanan History Isn’t Over Yet: Illiberalism and the Rise of China Andrew Spearing Climate and Political Justice: Investing in the Developing World Harry Zehner Domestic Policy and Global Repercussions The Global Implications of Changing American Trade Policy Kyle Adams Brexit: European History and the Implications for Democracy Fizza Alam National Security and Democratic Liberty in the Information Age Emma DeGrandi The Unconventional Role and Rhetoric of the Presidency Marianna Kalander The Resurgence of Conservatism in Britain and the United States Chineze Osakawe Gun Laws and Regulations Throughout the World Aylin Saydam A Letter from the Editor On behalf of the Editorial Board and the Department of Political Science, it is my pleasure to present the Fall 2018 Edition of the Undergraduate Political Review. As the student- run affiliate of the Department of Political Science at the University of Connecticut, UPR has a long and documented history of identifying and illuminating the formative political issues of our time. -

Digital Culture Media and Sport Committee

ELECTORAL MATTERS COMMITTEE Inquiry into the Impact of Social Media on Elections and Electoral Administration Melbourne—Thursday, 19 November 2020 (via videoconference) MEMBERS Mr Lee Tarlamis—Chair Ms Wendy Lovell Mrs Bev McArthur—Deputy Chair Mr Andy Meddick Ms Lizzie Blandthorn Mr Cesar Melhem Mr Matthew Guy Mr Tim Quilty Ms Katie Hall Dr Tim Read Thursday, 19 November 2020 Electoral Matters Committee 41 WITNESS Mr Julian Knight, MP, Chair, Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, UK Parliament. The CHAIR: I declare open the public hearing for the Electoral Matters Committee Inquiry into the Impact of Social Media on Elections and Electoral Administration. I would like to begin this hearing by respectfully acknowledging the Aboriginal peoples, the traditional custodians of the various lands each of us are gathered on today, and pay my respects to their ancestors, elders and families. I particularly welcome any elders or community members who are here today to impart their knowledge of this issue to the committee or who are watching the broadcast of these proceedings. I welcome Julian Knight, MP, Chair of the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee at the UK Parliament. I am Lee Tarlamis, Chair of the committee and a Member for South Eastern Metropolitan Region. The other members of the committee here today are Bev McArthur, our Deputy Chair and a Member for Western Victoria; the Honourable Wendy Lovell, a Member for Northern Victoria; Andy Meddick, a Member for Western Victoria; and Dr Tim Read, the Member for Brunswick. All evidence taken by this committee is protected by parliamentary privilege; therefore you are protected against any action in Australia for what you say here today. -

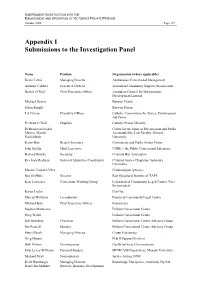

Appendix I Submissions to the Investigation Panel

INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATION INTO THE MANAGEMENT AND OPERATION OF VICTORIA’S PRIVATE PRISONS October 2000 Page 119 Appendix I Submissions to the Investigation Panel Name Position Organisation (where applicable) Kevin Lewis Managing Director Australasian Correctional Management Anthony Calabro Executive Director Australian Community Support Organisation Dennis O’Neill Chief Executive Officer Australian Council for Infrastructure Development Limited Michael Dennis Barwon Prison Julian Knight Barwon Prison Liz Curran Executive Officer Catholic Commission for Justice, Development and Peace Fr Grant O’Neill Chaplain Catholic Prison Ministry Dr Bronwyn Naylor Centre for the Study of Privatisation and Public Martine Marich Accountability, Law Faculty, Monash Gail Hubble University Karen Batt Branch Secretary Community and Public Sector Union John Griffin Chief Executive CORE – the Public Correctional Enterprise Richard Bourke Secretary Criminal Bar Association Rev Judy Redman Outreach Ministries Coordinator Criminal Justice Chaplains’ Advisory Committee Maartje Van-der-Vlies Criminologist (private) Ray Griffiths Director East Gippsland Institute of TAFE Kate Lawrence Corrections Working Group Federation of Community Legal Centres (Vic) Incorporated Karen Taylor Flat Out Marcus Williams Co-ordinator Footscray Community Legal Centre Michael Burt Chief Executive Officer Forensicare Stephen Masterson Fulham Correctional Centre Greg Welsh Fulham Correctional Centre Bill Henebery Chairman Fulham Correctional Centre Advisory Group Jim Pennell Member Fulham