A Bright Millisecond-Duration Radio Burst from a Galactic Magnetar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

• Classifying Stars: HR Diagram • Luminosity, Radius, and Temperature • “Vogt-Russell” Theorem • Main Sequence • Evolution on the HR Diagram

Stars • Classifying stars: HR diagram • Luminosity, radius, and temperature • “Vogt-Russell” theorem • Main sequence • Evolution on the HR diagram Classifying stars • We now have two properties of stars that we can measure: – Luminosity – Color/surface temperature • Using these two characteristics has proved extraordinarily effective in understanding the properties of stars – the Hertzsprung- Russell (HR) diagram If we plot lots of stars on the HR diagram, they fall into groups These groups indicate types of stars, or stages in the evolution of stars Luminosity classes • Class Ia,b : Supergiant • Class II: Bright giant • Class III: Giant • Class IV: Sub-giant • Class V: Dwarf The Sun is a G2 V star Luminosity versus radius and temperature A B R = R R = 2 RSun Sun T = T T = TSun Sun Which star is more luminous? Luminosity versus radius and temperature A B R = R R = 2 RSun Sun T = T T = TSun Sun • Each cm2 of each surface emits the same amount of radiation. • The larger stars emits more radiation because it has a larger surface. It emits 4 times as much radiation. Luminosity versus radius and temperature A1 B R = RSun R = RSun T = TSun T = 2TSun Which star is more luminous? The hotter star is more luminous. Luminosity varies as T4 (Stefan-Boltzmann Law) Luminosity Law 2 4 LA = RATA 2 4 LB RBTB 1 2 If star A is 2 times as hot as star B, and the same radius, then it will be 24 = 16 times as luminous. From a star's luminosity and temperature, we can calculate the radius. -

ASTR 545 Module 2 HR Diagram 08.1.1 Spectral Classes: (A) Write out the Spectral Classes from Hottest to Coolest Stars. Broadly

ASTR 545 Module 2 HR Diagram 08.1.1 Spectral Classes: (a) Write out the spectral classes from hottest to coolest stars. Broadly speaking, what are the primary spectral features that define each class? (b) What four macroscopic properties in a stellar atmosphere predominantly govern the relative strengths of features? (c) Briefly provide a qualitative description of the physical interdependence of these quantities (hint, don’t forget about free electrons from ionized atoms). 08.1.3 Luminosity Classes: (a) For an A star, write the spectral+luminosity class for supergiant, bright giant, giant, subgiant, and main sequence star. From the HR diagram, obtain approximate luminosities for each of these A stars. (b) Compute the radius and surface gravity, log g, of each luminosity class assuming M = 3M⊙. (c) Qualitative describe how the Balmer hydrogen lines change in strength and shape with luminosity class in these A stars as a function of surface gravity. 10.1.2 Spectral Classes and Luminosity Classes: (a,b,c,d) (a) What is the single most important physical macroscopic parameter that defines the Spectral Class of a star? Write out the common Spectral Classes of stars in order of increasing value of this parameter. For one of your Spectral Classes, include the subclass (0-9). (b) Broadly speaking, what are the primary spectral features that define each Spectral Class (you are encouraged to make a small table). How/Why (physically) do each of these depend (change with) the primary macroscopic physical parameter? (c) For an A type star, write the Spectral + Luminosity Class notation for supergiant, bright giant, giant, subgiant, main sequence star, and White Dwarf. -

Ptrsa, 365, 1307, 2007

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A (2007) 365, 1307–1313 doi:10.1098/rsta.2006.1998 Published online 9 February 2007 Giant flares in soft g-ray repeaters and short GRBs BY S. ZANE* Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College of London, Holmbury St Mary, Dorking, Surrey RH5 6NT, UK Soft gamma-ray repeaters (SGRs) are a peculiar family of bursting neutron stars that, occasionally, have been observed to emit extremely energetic giant flares (GFs), with energy release up to approximately 1047 erg sK1. These are exceptional and rare events. It has been recently proposed that GFs, if emitted by extragalactic SGRs, may appear at Earth as short gamma-ray bursts. Here, I will discuss the properties of the GFs observed in SGRs, with particular emphasis on the spectacular event registered from SGR 1806-20 in December 2004. I will review the current scenario for the production of the flare, within the magnetar model, and the observational implications. Keywords: soft gamma-ray repeaters; short gamma-ray bursts; stars: neutron 1. Introduction Soft gamma-ray repeaters (SGRs) are a small group (four known sources and one candidate) of neutron stars (NSs) discovered as bursting gamma-ray sources. During the quiescent state (i.e. outside bursts events), these sources are detected as persistent emitters in the soft X-ray range (less than 10 keV), with a luminosity of approximately 1035 erg sK1 and with a typical blackbody plus power law spectrum. Their NS nature is probed by the detection of periodic X-ray pulsations at a few seconds in three cases. Very recently, a hard and pulsed emission (20–100 keV) has been discovered in two sources (Mereghetti et al. -

Lithium Abundances in Fast Rotating Bright Giant Stars

Stellar Rotation Proceedings [AU Symposium No. 215, © 2003 [AU Andre Maeder & Philippe Eenens, eds. Lithium Abundances in Fast Rotating Bright Giant Stars J.D.Jr do NascimentoI, A. Lebre", R. Konstantinova-Antova' and J. R. De Medeiros! I-Departamento de Fisico Teorica e Experimental, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 59072-970 Natal, R.N., Brazil; 2-GRAAL, UMR 5024 ISTEEM/CNRS, CC 072, Uniuersiie Montpellier II, F-34095 Montpellier Cedex, France; 3 Institute of Astronomy, 72 Tsarigradsko shose, BG-1784 Sofia, Bulgaria Abstract. We present the results of high resolution spectroscopic observations of Li I resonance doublet at A6707.8 A for fast rotating single stars of luminosity class II and lb. We present a discussion on the link between rotation and Li content in intermediate mass giant stars, with emphasis on their evolutionary status. At least one of the observed stars, HD 232862, a G8I1 with an unusual vsini of 20 km/s, present a Li-rich behavior. 1. The Problem and Observations This work brings the first results of a large observational campaign to deter- mine Li, rotation and CNO abundances for a sample of single bright giants and Ib supergiants, along the spectral region F, G and K. Measurements of Li and CNO surface content of evolved stars is of paramount importance to test quan- titative and qualitative theoretical predictions of the effects of nucleosynthesis and subsequent mixing events on the stellar surface abundances. A survey of bright giants and Ib supergiants along the spectral region F, G and K, has been carried out to study the possible link between the rotational be- havior and CNO abundances (do Nascimento & De Medeiros 2003). -

15.2 Patterns Among Stars

15.2 Patterns Among Stars Our goals for learning: What is a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram? What is the significance of the main sequence? What are giants, supergiants, and white dwarfs? Why do the properties of some stars vary? What is a Hertzsprung- Russell diagram? An H-R diagram plots the luminosity and temperature of stars. Luminosity Temperature Most stars fall somewhere on the main sequence of the H-R diagram. Stars with lower T and higher L than main- sequence stars must have larger radii. These stars are called giants and supergiants. Stars with higher T and lower L than main- sequence stars must have smaller radii. These stars are called white dwarfs. Stellar Luminosity Classes A star's full classification includes spectral type (line identities) and luminosity class (line shapes, related to the size of the star): I - supergiant II - bright giant III - giant IV - subgiant V - main sequence Examples: Sun - G2 V Sirius - A1 V Proxima Centauri - M5.5 V Betelgeuse - M2 I H-R diagram depicts: Temperature Color Spectral type Luminosity Luminosity Radius Temperature Which star is the hottest? Luminosity Temperature Which star is the hottest? A Luminosity Temperature Which star is the most luminous? Luminosity Temperature Which star is the most luminous? C Luminosity Temperature Which star is a main- sequence star? Luminosity Temperature Which star is a main- sequence star? D Luminosity Temperature Which star has the largest radius? Luminosity Temperature Which star has the largest radius? Luminosity C Temperature What is the significance of the main sequence? Main-sequence stars are fusing hydrogen into helium in their cores like the Sun. -

The History of Star Formation in Galaxies

Astro2010 Science White Paper: The Galactic Neighborhood (GAN) The History of Star Formation in Galaxies Thomas M. Brown ([email protected]) and Marc Postman ([email protected]) Space Telescope Science Institute Daniela Calzetti ([email protected]) Dept. of Astronomy, University of Massachusetts 24 25 26 I 27 28 29 30 0.5 1.0 1.5 V-I Brown et al. The History of Star Formation in Galaxies Abstract If we are to develop a comprehensive and predictive theory of galaxy formation and evolution, it is essential that we obtain an accurate assessment of how and when galaxies assemble their stel- lar populations, and how this assembly varies with environment. There is strong observational support for the hierarchical assembly of galaxies, but by definition the dwarf galaxies we see to- day are not the same as the dwarf galaxies and proto-galaxies that were disrupted during the as- sembly. Our only insight into those disrupted building blocks comes from sifting through the re- solved field populations of the surviving giant galaxies to reconstruct the star formation history, chemical evolution, and kinematics of their various structures. To obtain the detailed distribution of stellar ages and metallicities over the entire life of a galaxy, one needs multi-band photometry reaching solar-luminosity main sequence stars. The Hubble Space Telescope can obtain such data in the outskirts of Local Group galaxies. To perform these essential studies for a fair sample of the Local Universe will require observational capabilities that allow us to extend the study of resolved stellar populations to much larger galaxy samples that span the full range of galaxy morphologies, while also enabling the study of the more crowded regions of relatively nearby galaxies. -

Spectroscopy of Variable Stars

Spectroscopy of Variable Stars Steve B. Howell and Travis A. Rector The National Optical Astronomy Observatory 950 N. Cherry Ave. Tucson, AZ 85719 USA Introduction A Note from the Authors The goal of this project is to determine the physical characteristics of variable stars (e.g., temperature, radius and luminosity) by analyzing spectra and photometric observations that span several years. The project was originally developed as a The 2.1-meter telescope and research project for teachers participating in the NOAO TLRBSE program. Coudé Feed spectrograph at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Ari- Please note that it is assumed that the instructor and students are familiar with the zona. The 2.1-meter telescope is concepts of photometry and spectroscopy as it is used in astronomy, as well as inside the white dome. The Coudé stellar classification and stellar evolution. This document is an incomplete source Feed spectrograph is in the right of information on these topics, so further study is encouraged. In particular, the half of the building. It also uses “Stellar Spectroscopy” document will be useful for learning how to analyze the the white tower on the right. spectrum of a star. Prerequisites To be able to do this research project, students should have a basic understanding of the following concepts: • Spectroscopy and photometry in astronomy • Stellar evolution • Stellar classification • Inverse-square law and Stefan’s law The control room for the Coudé Description of the Data Feed spectrograph. The spec- trograph is operated by the two The spectra used in this project were obtained with the Coudé Feed telescopes computers on the left. -

Exam Study Tips Exam 1 Will Cover the Day of the Exam

Astronomy Picture of the day ASTR 1020: Stars & Galaxies February 18, 2008 • MasteringAstronomy Homework on The HR Diagram is due Feb. 25th. • Reading: Chapter 15, section 15.2. • Exam 1: February 20thth. (Next Class) Young Stars in the Rho Ophiuchi Cloud Cosmic dust clouds and embedded newborn stars glow at infrared wavelengths in this tantalizing false-color view from the Spitzer Space Telescope. 400 ly distance, view is 5 ly across. 1 2 Exam Study Tips Exam 1 will cover • Study with a friend! • Check PowerPoints (on class website) against • All material discussed in class, readings, your notes, homeworks- are you comfortable and tutorial up through today’s class. with the relevant concepts? • Textbook: Chapters 1 (Sections 1.1-1.2), • Do more quiz and review questions in your text and in MasteringAstronomy. Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 14, Chapter • Check out textbook “Learning Goals” at the 15. beginning of each textbook Chapter and Key • MasteringAstronomy Homeworks on Concepts at end of Chapter. “Scales of the Universe”, “Light and • Review Clicker Questions. Spectroscopy”, “The Sun”, and “The • Exam is closed book but you may bring one sheet of paper (both sides) with notes. Properties of Stars”. 3 4 • Can you use the formula? Examples in The Day of the Exam class, homeworks, sample questions. Bring a #2 pencil and eraser • You may need to “invert” the equation– for example, solve for T using the equation: Bring a calculator if you think you’ll need one wavelength = 2,900,000 nm / T Please be prepared to get started right away -

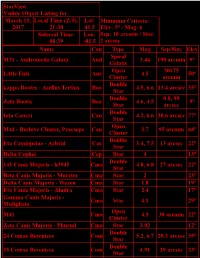

Starview Visible Object Listing For: March 15, 2017 Local Time

StarView Visible Object Listing for: March 15, Local Time (Z5): Lat: Minimum Criteria: 2017 21:30 41.5 Elev: 5° / Mag: 6 Sidereal Time: Lon: Sep: 10 arcmin / Size: 08:39 81.5 2 arcsec Name Con Type Mag Sep/Size Elev Spiral M31 Andromeda Galaxy And 3.44 190 arcmin 9° Galaxy Open 30x75 Little Fish Aur 4.5 50° Cluster arcmin Double kappa Bootes Asellus Tertius Boo 4.5, 6.6 13.4 arcsec 35° Star Double 0.8, 99 Zeta Bootis Boo 4.6, 4.5 9° Star arcsec Double Iota Cancri Can 4.2, 6.6 30.6 arcsec 77° Star Open M44 Beehive Cluster, Praesepe Can 3.7 95 arcmin 68° Cluster Double Eta Cassiopeiae Achrid Cas 3.4, 7.5 13 arcsec 22° Star Delta Cephei Cep Star 4 13° Double 145 Canis Majoris h3945 Cma 4.8, 6.8 27 arcsec 22° Star Beta Canis Majoris Murzim Cma Star 2 23° Delta Canis Majoris Wezen Cma Star 1.8 19° Eta Canis Majoris Aludra Cma Star 2.4 17° Gamma Canis Majoris Cma Star 4.1 29° Muliphein Open M41 Cma 4.5 38 arcmin 22° Cluster Zeta Canis Majoris Phurud Cma Star 3.02 12° Double 24 Comae Berenices Com 5.2, 6.7 20.3 arcsec 35° Star Double 35 Comae Berenices Com 4.91 29 arcsec 33° Star Alpha Canum Venaticorum Cor CVn Double 2.9, 5.5 19.6 arcsec 42° Caroli Star Y Cvn La Superba Cvn Star 5 46° Double Nu Draconis Dra 4.88 63.4 arcsec 14° Star Omicron 2 Eridani Keid, Beid, Double Eri 4.5. -

Vigorous Atmospheric Motions in the Red Supergiant Supernova Progenitor Antares

Vigorous atmospheric motions in the red supergiant supernova progenitor Antares K. Ohnaka1, G. Weigelt2 & K.-H. Hofmann2 1. Instituto de Astronom´ıa, Universidad Catolica´ del Norte, Avenida Angamos 0610, Antofagasta, Chile 2. Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hugel¨ 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany Red supergiants represent a late stage of the evolution of stars more massive than about 9 solar masses. At this evolutionary stage, massive stars develop complex, multi-component at- mospheres. Bright spots were detected in the atmosphere of red supergiants by interferometric imaging1–5. Above the photosphere, the molecular outer atmosphere extends up to about two stellar radii6–14. Furthermore, the hot chromosphere (5,000–8,000 K) and cool gas (<3,500 K) are coexisting within ∼3 stellar radii15–18. The dynamics of the complex atmosphere have been probed by ultraviolet and optical spectroscopy19–22. However, the most direct, unambiguous approach is to measure the velocity at each position over the image of stars as in observations of the Sun. Here we report mapping of the velocity field over the surface and atmosphere of the prototypical red supergiant Antares. The two-dimensional velocity field map obtained from our near-infrared spectro-interferometric imaging reveals vigorous upwelling and downdraft- ing motions of several huge gas clumps at velocities ranging from about −20 to +20 km s−1 in the atmosphere extending out to ∼1.7 stellar radii. Convection alone cannot explain the ob- served turbulent motions and atmospheric extension, suggesting the operation of a yet-to-be identified process in the extended atmosphere. +35 Antares is a well-studied, close red supergiant (RSG) at a distance of 170−25 pc (based on the parallax of 5:891:00 milliarcsecond = mas, ref. -

Astronomy General Information

ASTRONOMY GENERAL INFORMATION HERTZSPRUNG-RUSSELL (H-R) DIAGRAMS -A scatter graph of stars showing the relationship between the stars’ absolute magnitude or luminosities versus their spectral types or classifications and effective temperatures. -Can be used to measure distance to a star cluster by comparing apparent magnitude of stars with abs. magnitudes of stars with known distances (AKA model stars). Observed group plotted and then overlapped via shift in vertical direction. Difference in magnitude bridge equals distance modulus. Known as Spectroscopic Parallax. SPECTRA HARVARD SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (1-D) -Groups stars by surface atmospheric temp. Used in H-R diag. vs. Luminosity/Abs. Mag. Class* Color Descr. Actual Color Mass (M☉) Radius(R☉) Lumin.(L☉) O Blue Blue B Blue-white Deep B-W 2.1-16 1.8-6.6 25-30,000 A White Blue-white 1.4-2.1 1.4-1.8 5-25 F Yellow-white White 1.04-1.4 1.15-1.4 1.5-5 G Yellow Yellowish-W 0.8-1.04 0.96-1.15 0.6-1.5 K Orange Pale Y-O 0.45-0.8 0.7-0.96 0.08-0.6 M Red Lt. Orange-Red 0.08-0.45 *Very weak stars of classes L, T, and Y are not included. -Classes are further divided by Arabic numerals (0-9), and then even further by half subtypes. The lower the number, the hotter (e.g. A0 is hotter than an A7 star) YERKES/MK SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (2-D!) -Groups stars based on both temperature and luminosity based on spectral lines. -

Basic Astronomy Labs

Astronomy Laboratory Exercise 31 The Magnitude Scale On a dark, clear night far from city lights, the unaided human eye can see on the order of five thousand stars. Some stars are bright, others are barely visible, and still others fall somewhere in between. A telescope reveals hundreds of thousands of stars that are too dim for the unaided eye to see. Most stars appear white to the unaided eye, whose cells for detecting color require more light. But the telescope reveals that stars come in a wide palette of colors. This lab explores the modern magnitude scale as a means of describing the brightness, the distance, and the color of a star. The earliest recorded brightness scale was developed by Hipparchus, a natural philosopher of the second century BCE. He ranked stars into six magnitudes according to brightness. The brightest stars were first magnitude, the second brightest stars were second magnitude, and so on until the dimmest stars he could see, which were sixth magnitude. Modern measurements show that the difference between first and sixth magnitude represents a brightness ratio of 100. That is, a first magnitude star is about 100 times brighter than a sixth magnitude star. Thus, each magnitude is 100115 (or about 2. 512) times brighter than the next larger, integral magnitude. Hipparchus' scale only allows integral magnitudes and does not allow for stars outside this range. With the invention of the telescope, it became obvious that a scale was needed to describe dimmer stars. Also, the scale should be able to describe brighter objects, such as some planets, the Moon, and the Sun.