Historic Concrete in Scotland Part 1: History and Development ISBN 978-1-84917-119-9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Lairds of Grant and Earls of Seafield

t5^ %• THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY GAROWNE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD. THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY A HISTORY OF THE LAIRDS OF GRANT AND EARLS OF SEAFIELD BY THE EARL OF CASSILLIS " seasamh gu damgean" Fnbemess THB NORTHERN COUNTIES NEWSPAPER AND PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED 1911 M csm nil TO CAROLINE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD, WHO HAS SO LONG AND SO ABLY RULED STRATHSPEY, AND WHO HAS SYMPATHISED SO MUCH IN THE PRODUCTION OP THIS HISTORY, THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE The material for " The Rulers of Strathspey" was originally collected by the Author for the article on Ogilvie-Grant, Earl of Seafield, in The Scots Peerage, edited by Sir James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon King of Arms. A great deal of the information collected had to be omitted OAving to lack of space. It was thought desirable to publish it in book form, especially as the need of a Genealogical History of the Clan Grant had long been felt. It is true that a most valuable work, " The Chiefs of Grant," by Sir William Fraser, LL.D., was privately printed in 1883, on too large a scale, however, to be readily accessible. The impression, moreover, was limited to 150 copies. This book is therefore published at a moderate price, so that it may be within reach of all the members of the Clan Grant, and of all who are interested in the records of a race which has left its mark on Scottish history and the history of the Highlands. The Chiefs of the Clan, the Lairds of Grant, who succeeded to the Earldom of Seafield and to the extensive lands of the Ogilvies, Earls of Findlater and Seafield, form the main subject of this work. -

Cromdale & Advie Community Council

CROMDALE & ADVIE COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES OF MEETING of Weds 6th Feb 2013 at 7PM Cromdale Village Hall Present Apologies Non –Apologies Iain Reid (IR) Suzanne Mayle (SM) Ann Whiting (AW) Mrs Yvonne Simpson (YS) Dougie Gibson (DG) Northern Cllr Jaci Douglas (JD) Constabulary (NC) Ralph Newlands - BEAR (RN) Carl Stewart -public Pat Fowler - public Pam Gordon - public John Robson - public Jenny Robson - public Pam Brand - public 7:15pm Meeting opened - in the absence of a Chair, IR chaired the meeting. Minutes of Previous Meeting The minutes of the meeting held 5th December were retrospectively agreed by Suzanne Mayle and seconded by Dougie Gibson. Office Bearers: Iain Reid has received a letter of resignation from the Community Council from Ivan McConachie, effective immediately. JD advises that a Chair will need to be selected from the ELECTED Members prior to the upcoming AGM. The make-up of the Community Council now has 3 vacancies, however there are 3 residents willing to get involved - Carl Stewart, Ewan Grant and Rosemary Shreeve. The Community Council will take steps to approach these people and co-opt them prior to the AGM. Matters arising/ongoing items 1. Police Issues - the regular monthly report had been submitted by NC via email. It does not breakdown statistics for the parish as such but seems to include them within the Grantown-on-Spey figures. IR has emailed Inspector MacLeod to see if Cromdale & Advie can be presented with statistics for the parish separately. 2. Bank Account – SM advised via email that the balance of the accounts currently stood at £3807.07 and that the new signatory regime has been put in place. -

Intimations Surnames L

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames L This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames L Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage L’AMY / SCOTT 1863 Sylvester L’Amy, London, to Margaret Sinclair, 2nd daughter of John Scott, Finnart, Greenock, at St George’s, London on 6th May 1863.. see Margaret S. (Greenock Advertiser 9.5.1863) Marriage LACHLAN / 1891 Alexander McLeod to Lizzie, youngest daughter of late MCLEOD James Lachlan, at Arcade Hall, Greenock on 5th February 1891 (Greenock Telegraph 09.02.1891) Marriage LACHLAN / SLATER 1882 Peter, eldest son of John Slater, blacksmith to Mary, youngest daughter of William Lachlan formerly of Port Glasgow at 9 Plantation Place, Port Glasgow on 21.04.1882. (Greenock Telegraph 24.04.1882) see Mary L Death LACZUISKY 1869 Maximillian Maximillian Laczuisky died at 5 Clarence Street, Greenock on 26th December 1869. -

Black's Morayshire Directory, Including the Upper District of Banffshire

tfaU. 2*2. i m HE MOR CTORY. * i e^ % / X BLACKS MORAYSHIRE DIRECTORY, INCLUDING THE UPPER DISTRICTOF BANFFSHIRE. 1863^ ELGIN : PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES BLACK, ELGIN COURANT OFFICE. SOLD BY THE AGENTS FOR THE COURANT; AND BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : ELGIN PRINTED AT THE COURANT OFFICE, PREFACE, Thu ''Morayshire Directory" is issued in the hope that it will be found satisfactorily comprehensive and reliably accurate, The greatest possible care has been taken in verifying every particular contained in it ; but, where names and details are so numerous, absolute accuracy is almost impossible. A few changes have taken place since the first sheets were printed, but, so far as is known, they are unimportant, It is believed the Directory now issued may be fully depended upon as a Book of Reference, and a Guide for the County of Moray and the Upper District of Banffshire, Giving names and information for each town arid parish so fully, which has never before been attempted in a Directory for any County in the JTorth of Scotland, has enlarged the present work to a size far beyond anticipation, and has involved much expense, labour, and loss of time. It is hoped, however, that the completeness and accuracy of the Book, on which its value depends, will explain and atone for a little delay in its appearance. It has become so large that it could not be sold at the figure first mentioned without loss of money to a large extent, The price has therefore been fixed at Two and Sixpence, in order, if possible, to cover outlays, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/blacksmorayshire1863dire INDEX. -

Parish Profile for Abernethy Linked with Boat of Garten, Carrbridge and Kincardine

Parish Profile for Abernethy linked with Boat of Garten, Carrbridge and Kincardine www.abck-churches.org.uk Church of Scotland Welcome! The church families in the villages of Abernethy, Boat of Garten, Carrbridge and Kincardine are delighted you are reading this profile of our very active linked Church of Scotland charge, based close to the Cairngorm Mountains, adjacent to the River Spey and surrounded by the forests and lochs admired and enjoyed by so many. As you read through this document we hope it will help you to form a picture of the life and times of our churches here in the heart of Strathspey. Our hope, too, is that it will encourage you to pray specifically about whether God is calling you to join us here to share in the ministry of growing and discipling God’s people plus helping us to reach out to others with the good news of Jesus Christ. Please be assured that many here are praying for the person of God’s choosing. There may be lots of questions which arise from reading our profiles. Please do not hesitate to lift the phone, or send off a quick email to any of the names on the Contacts page including our Interim Moderator, Bob Anderson. We’d love to hear from you. Church of Scotland Contents of the Profile 1. Welcome to our churches. (2) 2. Description of the person we are looking for to join our teams (4) 3. History of the linkage including a map of the villages. (5/6) 4. The Manse and its setting. -

Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Database Documentation and Description

1 Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Database Documentation and Description Contents of this Document I. Database Description (pp. 2-14) A. Description B. Database field types C. Miscellaneous database information D. Entity Models 1. Overview 2. Case attributes 3. Trial attributes II. List of tables and fields (pp. 15-29) III. Data Value Descriptions (pp. 30-41) IV. Database Provenance (pp. 42-54) A. Descriptions of sources used B. Full bibliography of primary, printed primary and secondary sources V. Methodology (pp. 55-58) VI. Appendices (pp. 59-78) A. Modernised/Standardised Last Names B. Modernised/Standardised First Names C. Parish List – all parishes in seventeenth century Scotland D. Burgh List – Royal burghs in 1707 E. Presbytery List – Presbyteries used in the database F. County List – Counties used in the database G. Copyright and citation protocol 2 Database Documents I. DATABASE DESCRIPTION A. DESCRIPTION (in text form) DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY OF SCOTTISH WITCHCRAFT DATABASE INTRODUCTION The following document is a description and guide to the layout and design of the ‘Survey of Scottish Witchcraft’ database. It is divided into two sections. In the first section appropriate terms and concepts are defined in order to afford accuracy and precision in the discussion of complicated relationships encompassed by the database. This includes relationships between accused witches and their accusers, different accused witches, people and prosecutorial processes, and cultural elements of witchcraft belief and the processes through which they were documented. The second section is a general description of how the database is organised. Please see the document ‘Description of Database Fields’ for a full discussion of every field in the database, including its meaning, use and relationships to other fields and/or tables. -

A Way Forward Draft Community Action Plan Advie 2008

OUR COMMUNITY……….A WAY FORWARD DRAFT COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN ADVIE 2008 OUR COMMUNITY .. A WAY FORWARD Background Our Community .. A Way Forward was carried out as a pilot project, covering the communities of Grantown-on-Spey, Cromdale/Advie and Dulnain Bridge. The work involved gathering information on housing, social and economic issues; conducting a survey of all households; and organising a range of community consultation activities. Residents were asked to identify the best things about their community as well as improvements. Following an analysis of the information and community feedback obtained, priorities for action have been identified. Individual action plans will be finalised in discussion with the project Steering Group and each community. Advie – An Overview Households from Advie and Cromdale were included in the same survey. Findings therefore relate to both communities. In addition, most of the statistical data and information obtained was for both Advie and Cromdale. Population Advie’s population has remained relatively static over the last few years but is projected to increase over the course of the next decade, with the number of households increasing at a faster rate. The population is ageing with a growing proportion of residents aged 60 or over. Employment and the Economy The local economy is reported to be relatively buoyant. Employment patterns are similar to the rest of Highland although there is a tendency for both male and female employees to work longer hours. Agriculture continues to be an important employer, with tourism also important to the local area. Housing Compared to the rest of Highland there is a higher proportion of empty properties and a much higher proportion of private rented accommodation and tied housing. -

Resource Efficiency Directory

Services to Business Resource Efficiency Directory Is Your Profit Going to Waste? Prior to publication, the Resource Efficiency Directory, won the silver Green Apple Award, 2004, in recognition of its positive and novel contribution to encouraging environmental good practise within the business community. Contents Page Introduction 2 The Challenge 3 The Solution 4 General Office 8 Catering, Hospitality and Leisure 18 Transport 26 Packaging 29 Construction and Demolition 31 Horticulture and Grounds Maintenance 34 Manufacturing and Product Design 36 Chemicals 38 Waste Management and Disposal 39 A-Z Summary 41 External Drivers 42 Further Support 46 Full Contact Details 50 If you require this publication in an alternative format and/or language, please contact the Scottish Enterprise Helpline on 0845 607 8787 to discuss your needs. Disclaimer Whilst every effort has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information in the following pages, the authors of this guide accept no responsibility for errors, omissions, amendments or suitability. Introduction Resource Efficiency is an opportunity to boost your profits and your profile. Policy-makers, funding providers, suppliers and customers are influenced by how sustainable you are. This directory helps you become as efficient as possible. What does the Directory Offer? There’s lots of support to help your business become sustainable. This directory puts all the information you need in one place, with specific information for the Dunbartonshire area. The directory will: •explain how to use resources efficiently, showing the benefits to your business • list the sustainable development issues for business, with advice on how to tackle them • give you details of local organisations that provide support •explain issues such as the law and award schemes • give you contacts for further sources of information and support All this information will help you identify the ideas and services which are right for your business. -

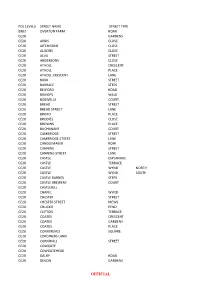

Applicant Data

POL LEVEL5 STREET NAME STREET TYPE BX02 OVERTON FARM ROAD CE20 GARDENS CE20 AIRDS CLOSE CE20 AITCHISONS CLOSE CE20 ALISONS CLOSE CE20 ALVA STREET CE20 ANDERSONS CLOSE CE20 ATHOLL CRESCENT CE20 ATHOLL PLACE CE20 ATHOLL CRESCENT LANE CE20 BANK STREET CE20 BARRACE STEPS CE20 BELFORD ROAD CE20 BISHOPS WALK CE20 BOSWELLS COURT CE20 BREAD STREET CE20 BREAD STREET LANE CE20 BRISTO PLACE CE20 BRODIES CLOSE CE20 BROWNS PLACE CE20 BUCHANANS COURT CE20 CAMBRIDGE STREET CE20 CAMBRIDGE STREET LANE CE20 CANDLEMAKER ROW CE20 CANNING STREET CE20 CANNING STREET LANE CE20 CASTLE ESPLANADE CE20 CASTLE TERRACE CE20 CASTLE WYND NORTH CE20 CASTLE WYND SOUTH CE20 CASTLE BARNES STEPS CE20 CASTLE BREWERY COURT CE20 CASTLEHILL CE20 CHAPEL WYND CE20 CHESTER STREET CE20 CHESTER STREET MEWS CE20 CHUCKIE PEND CE20 CLIFTON TERRACE CE20 COATES CRESCENT CE20 COATES GARDENS CE20 COATES PLACE CE20 CONFERENCE SQUARE CE20 CORDINERS LAND CE20 CORNWALL STREET CE20 COWGATE CE20 COWGATEHEAD CE20 DALRY ROAD CE20 DEVON GARDENS OFFICIAL CE20 DEVON PLACE CE20 DEWAR PLACE CE20 DEWAR PLACE LANE CE20 DOUGLAS CRESCENT CE20 DOUGLAS GARDENS CE20 DOUGLAS GARDENS MEWS CE20 DRUMSHEUGH GARDENS CE20 DRUMSHEUGH PLACE CE20 DUNBAR STREET CE20 DUNLOPS COURT CE20 EARL GREY STREET CE20 EAST FOUNTAINBRIDGE CE20 EDMONSTONES CLOSE CE20 EGLINTON CRESCENT CE20 FESTIVAL SQUARE CE20 FORREST HILL CE20 FORREST ROAD CE20 FOUNTAINBRIDGE CE20 GEORGE IV BRIDGE CE20 GILMOURS CLOSE CE20 GLADSTONES LAND CE20 GLENCAIRN CRESCENT CE20 GRANNYS GREEN STEPS CE20 GRASSMARKET CE20 GREYFRIARS PLACE CE20 GRINDLAY STREET CE20 -

Gps Coördinates Great Britain

GPS COÖRDINATES GREAT BRITAIN 21/09/14 Ingang of toegangsweg camping / Entry or acces way campsite © Parafoeter : http://users.telenet.be/leo.huybrechts/camp.htm Name City D Latitude Longitude Latitude Longitude 7 Holding (CL) Leadketty PKN 56.31795 -3.59494 56 ° 19 ' 5 " -3 ° 35 ' 42 " Abbess Roding Hall Farm (CL) Ongar ESS 51.77999 0.27795 51 ° 46 ' 48 " 0 ° 16 ' 41 " Abbey Farm Caravan Park Ormskirk LAN 53.58198 -2.85753 53 ° 34 ' 55 " -2 ° 51 ' 27 " Abbey Farm Caravan Park Llantysilio DEN 52.98962 -3.18950 52 ° 59 ' 23 " -3 ° 11 ' 22 " Abbey Gate Farm (CS) Axminster DEV 50.76591 -3.00915 50 ° 45 ' 57 " -3 ° 0 ' 33 " Abbey Green Farm (CS) Whixall SHR 52.89395 -2.73481 52 ° 53 ' 38 " -2 ° 44 ' 5 " Abbey Wood Caravan Club Site London LND 51.48693 0.11938 51 ° 29 ' 13 " 0 ° 7 ' 10 " Abbots House Farm Goathland NYO 54.39412 -0.70546 54 ° 23 ' 39 " -0 ° 42 ' 20 " Abbotts Farm Naturist Site North Tuddenham NFK 52.67744 1.00744 52 ° 40 ' 39 " 1 ° 0 ' 27 " Aberafon Campsite Caernarfon GWN 53.01021 -4.38691 53 ° 0 ' 37 " -4 ° 23 ' 13 " Aberbran Caravan Club Site Brecon POW 51.95459 -3.47860 51 ° 57 ' 17 " -3 ° 28 ' 43 " Aberbran Fach Farm Brecon POW 51.95287 -3.47588 51 ° 57 ' 10 " -3 ° 28 ' 33 " Aberbran Fawr Campsite Brecon POW 51.95151 -3.47410 51 ° 57 ' 5 " -3 ° 28 ' 27 " Abererch Sands Holiday Centre Pwllheli GWN 52.89703 -4.37565 52 ° 53 ' 49 " -4 ° 22 ' 32 " Aberfeldy Caravan Park Aberfeldy PKN 56.62243 -3.85789 56 ° 37 ' 21 " -3 ° 51 ' 28 " Abergwynant (CL) Snowdonia GWN 52.73743 -3.96164 52 ° 44 ' 15 " -3 ° 57 ' 42 " Aberlady Caravan -

Guilford County Planning & Inspections Street Listing 4/1/2021

Guilford County Planning & Inspections Street Listing 4/1/2021 Street Name City Jurisdiction Road Status Subdivision DR GREENSBORO RD 10TH ST GIBSONVILLE Gibsonville 11TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 12TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 14TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 15TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 16TH CT GREENSBORO 16TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 17TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 18TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 19TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 1ST ST HIGH POINT High Point 20TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 2ND ST GIBSONVILLE Gibsonville 32ND ST JAMESTOWN Jamestown 3RD ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 4TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 5TH AV GREENSBORO Greensboro 8TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro 9TH ST GREENSBORO Greensboro A C C LN GREENSBORO Greensboro A W MCALISTER DR GREENSBORO Greensboro ABB RD GIBSONVILLE ABBERTON WAY HIGH POINT ABBEY CT GREENSBORO Greensboro ABBEY GLEN DR GIBSONVILLE Gibsonville ABBEYDALE PL GREENSBORO Greensboro ABBEYWOOD PL HIGH POINT High Point Page 1 of 304 Street Name City Jurisdiction Road Status Subdivision ABBIE AV HIGH POINT High Point ABBOTS GLEN CT GREENSBORO Greensboro ABBOTT DR GREENSBORO Greensboro ABBOTT LOOP GUILFORD COUNTY ABBOTTS FORD CT HIGH POINT High Point ABE BRENNER PL GREENSBORO Greensboro ABELIA CT GREENSBORO Greensboro ABER RD WHITSETT ABERDARE DR HIGH POINT High Point ABERDEEN RD HIGH POINT High Point ABERDEEN TER GREENSBORO Greensboro ABERLOUR LN BURLINGTON Burlington ABERNATHY RD WHITSETT ABIGAIL LN GIBSONVILLE Gibsonville ABINGTON DR GREENSBORO Greensboro ABNER PL GREENSBORO Greensboro ABROSE GUILFORD ABSHIRE LN GREENSBORO Greensboro -

Historical Notes on Some Surnames and Patronymics Associated with the Clan Grant

Historical Notes on Some Surnames and Patronymics Associated with the Clan Grant Introduction In 1953, a little book entitled Scots Kith & Kin was first published in Scotland. The primary purpose of the book was to assign hundreds less well-known Scottish surnames and patronymics as ‘septs’ to the larger, more prominent highland clans and lowland families. Although the book has apparently been a commercial success for over half a century, it has probably disseminated more spurious information and hoodwinked more unsuspecting purchasers than any publication since Mao Tse Tung’s Little Red Book. One clue to the book’s lack of intellectual integrity is that no author, editor, or research authority is cited on the title page. Moreover, the 1989 revised edition states in a disclaimer that “…the publishers regret that they cannot enter into correspondence regarding personal family histories” – thereby washing their hands of having to defend, substantiate or otherwise explain what they have published. Anyone who has attended highland games or Scottish festivals in the United States has surely seen the impressive lists of so-called ‘sept’ names posted at the various clan tents. These names have also been imprinted on clan society brochures and newsletters, and more recently, posted on their websites. The purpose of the lists, of course, is to entice unsuspecting inquirers to join their clan society. These lists of ‘associated clan names’ have been compiled over the years, largely from the pages of Scots Kith & Kin and several other equally misleading compilations of more recent vintage. When I first joined the Clan Grant Society in 1977, I asked about the alleged ‘sept’ names and why they were assigned to our clan.