On Money • Coopérative Des Malassis • German Notgeld • Ray Beldner On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARTOGRAPHIC IMAGES of SLOVENIA THROUGH TIME KARTOGRAFSKE UPODOBITVE SLOVENIJE SKOZI ^AS Primo` Ga{Peri~

acta47-2.qxd 17.1.2008 7:26 Page 245 Acta geographica Slovenica, 47-2, 2007, 245–273 CARTOGRAPHIC IMAGES OF SLOVENIA THROUGH TIME KARTOGRAFSKE UPODOBITVE SLOVENIJE SKOZI ^AS Primo` Ga{peri~ PRIMO@ GA[PERI^ Cartographic material is a part of national cultural heritage. Kartografsko gradivo je del kulturne dedi{~ine vsakega naroda. acta47-2.qxd 17.1.2008 7:26 Page 246 Primo` Ga{peri~, Cartographic images of Slovenia through time Cartographic images of Slovenia through time UDC: 912.43(497.4)(091) 528.9(497.4)(091) COBISS: 1.02 ABSTRACT: The territory of Slovenia appears on Europe's oldest maps. Slovenia's location at the junction of differ- ent natural and geographical units and various political formations influenced its traffic and border situation. As a result, for many centuries the territory of Slovenia appeared inaccurately on maps and as part of for- eign national units. With the development of cartographical skills and the recognition of cartography in our area in the 16th century and especially from the 17th century on, Slovene territory was depicted equal- ly on maps of the times through the efforts of Slovene and foreign individuals. At first, maps of individual Slovene regions dominated, but from the middle of the 19th century there are more frequent depictions of the entire Slovene territory. Cartographical work thus also became a means of expressing national demands and hopes. KEY WORDS: geography, historical geography, maps, Slovenia The article was submitted for publication on October 5, 2006. ADDRESS: Primo` Ga{peri~, B. -

2019 International 25.05.2019 > 01.09.2019 Art Exhibitions 2019

International 05 Art Exhibitions 2019 International 25.05.2019 > 01.09.2019 Art Exhibitions 2019 Opposite page Portrait of Pope Benedict XVI 2010, Mixed media on board Michael Triegel 100.5 x 76 cm Institut Papst Benedikt XVI, Harmony in Discord Regensburg Museum de Fundatie Museum de Fundatie 1 2 5 Michael Triegel was born in Efurt, From 1990 to 1997 Michael Triegel The members of this association largely 1 Germany in 1968. He is a painter, studied at the renowned Hochschule use the same figurative form language, Persephone and Orpheus illustrator and graphic artist. His pain- für Grafik und Buchkunst (Academy of though they vary widely in terms of 2012, Mixed media on board Zwolle tings catapult us back in time. His body Fine Arts) in Leipzig, where he was their technique. 200 x 110 cm of work looks like it was created in the taught by Arno Rink and Ulrich Hachulla. Museum Barberini Potsdam early European Renaissance, but on The academy is closely associated with Having grown up in the secular GDR, 2 closer inspection it really is contempo- the Neue Leipziger Schule (New Leipzig Triegel converted to Christianity after Deus absconditus rary. It is a celebration of pure figurative School), a movement in German art the Bishop of Regensburg commi- 2013, Mixed media on canvas painting, with classic religious and pro- that arose following the fall of the Berlin ssioned him to paint a portrait of Pope 160 x 260 cm fane motifs, but Triegel also gives it an Wall, of which Neo Rauch is the most Benedict XVI in 2010. -

Fine Canadian Art

HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE HEFFEL FINE ART FINE CANADIAN ART FINE CANADIAN ART FINE CANADIAN ART MAY 27, 2015 MAY HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE VANCOUVER • CALGARY • TORONTO • OTTAWA • MONTREAL HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE ISBN 978~1~927031~17~9 SALE WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 2015, VANCOUVER FINE CANADIAN ART AUCTION WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 2015 4 PM, CANADIAN POST~WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 7 PM, FINE CANADIAN ART VANCOUVER CONVENTION CENTRE WEST BURRARD ENTRANCE, ROOM 211 1055 CANADA PLACE, VANCOUVER PREVIEW AT GALERIE HEFFEL, MONTREAL 1840 RUE SHERBROOKE OUEST THURSDAY, MAY 7 THROUGH SATURDAY, MAY 9, 11 AM TO 6 PM PREVIEW AT HEFFEL GALLERY, TORONTO 13 & 15 HAZELTON AVENUE THURSDAY, MAY 14 THROUGH SATURDAY, MAY 16, 11 AM TO 6 PM PREVIEW AT HEFFEL GALLERY, VANCOUVER SATURDAY, MAY 23 THROUGH TUESDAY, MAY 26, 11 AM TO 6 PM WEDNESDAY, MAY 27, 10 AM TO 12 PM HEFFEL GALLERY, VANCOUVER 2247 GRANVILLE STREET, VANCOUVER BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA V6H 3G1 TELEPHONE 604 732~6505, FAX 604 732~4245 TOLL FREE 1 800 528~9608 WWW.HEFFEL.COM HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE VANCOUVER • CALGARY • TORONTO • OTTAWA • MONTREAL HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE CATALOGUE SUBSCRIPTIONS A Division of Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel Fine Art Auction House and Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publish a variety of materials beneficial to the art collector. An VANCOUVER Annual Subscription entitles you to receive our Auction Catalogues 2247 Granville Street and Auction Result Sheets. Our Annual Subscription Form can be Vancouver, BC V6H 3G1 found on page 112 of this catalogue. Telephone -

Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017

PenrithIan Milliss: Regional Gallery & Modernism in Sydney and InternationalThe Lewers Trends Bequest Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017 Emu Island: Modernism in Place Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 1 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction 75 Years. A celebration of life, art and exhibition This year Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest celebrates 75 years of art practice and exhibition on this site. In 1942, Gerald Lewers purchased this property to use as an occasional residence while working nearby as manager of quarrying company Farley and Lewers. A decade later, the property became the family home of Gerald and Margo Lewers and their two daughters, Darani and Tanya. It was here the family pursued their individual practices as artists and welcomed many Sydney artists, architects, writers and intellectuals. At this site in Western Sydney, modernist thinking and art practice was nurtured and flourished. Upon the passing of Margo Lewers in 1978, the daughters of Margo and Gerald Lewers sought to honour their mother’s wish that the house and garden at Emu Plains be gifted to the people of Penrith along with artworks which today form the basis of the Gallery’s collection. Received by Penrith City Council in 1980, the Neville Wran led state government supported the gift with additional funds to create a purpose built gallery on site. Opened in 1981, the gallery supports a seasonal exhibition, education and public program. Please see our website for details penrithregionalgallery.org Cover: Frank Hinder Untitled c1945 pencil on paper 24.5 x 17.2 Gift of Frank Hinder, 1983 Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 2 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction Welcome to Penrith Regional Gallery & The of ten early career artists displays the on-going Lewers Bequest Spring Exhibition Program. -

Film Producer Buys Seacole Bust for 101 Times the Estimate

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2454 | antiquestradegazette.com | 15 August 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Face coverings Film producer buys Seacole now mandatory at auction rooms bust for 101 times the estimate across England A terracotta sculpture of Mary Seacole by Alex Capon (1805-81) sparked fierce competition at Dominic Winter. Wearing a face covering when Bidding at the South Cerney auction house attending an auction house in England began with 12 phones competing for the has now become mandatory. sculpture of Seacole, who nursed soldiers The updated guidance also applies to visitors to galleries and museums. during the Crimean War. Since July 24, face coverings have been It eventually came down to a final contest compulsory when on public transport as involving underbidder Art Aid and film well as in supermarkets and shops including producer Billy Peterson of Racing Green dealers’ premises and antique centres. The government announced that this Pictures, which is currently filming a would be extended in England from August biopic on Seacole’s life. 8 to include other indoor spaces such as Peterson will use the bust cinemas, theatres and places of worship. as a prop in the film. It will Auction houses also appear on this list. then be donated to the The measures, brought in by law, apply Mary Seacole Trust Continued on page 5 and be on view at the Florence Nightingale Museum. -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 29, 2019 Curated by Roberta Waddell

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 29, 2019 Curated by Roberta Waddell & Samantha Rippner with Consulting Printer Luther Davis April 4–June 15, 2019 Press Preview, Thursday, April 4, 10–11:30 AM Opening Reception, 6–8 PM, featuring live demonstration by Kayrock Screenprinting _ Charline von Heyl. Untitled, 2007. Screenprint with hand coloring. Sheet: 30 1/8 x 22 1/2 inches. Edition: Unique. Printed by Rob Swainston, Prints of Darkness; published by the artist. Image courtesy the artist and Prints of Darkness. © 2019 Charline von Heyl. Alex Dodge. In the wake of total happiness, 2013. UV screenprint with braille texture on museum board. Sheet: 20 x 32 inches. Edition: 30. Printed by Luther Davis, Axelle Editions; published by Forth Estate Editions. Image courtesy the artist, Forth Estate Editions, and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery. © 2019 Alex Dodge. Nicole Eisenman. Tea Party, 2012. Lithograph. Sheet: 48 3/4 x 37 1/8 inches. Edition: 25. Printed and published by Andrew Mockler, Jungle Press Editions. Image courtesy the artist and Jungle Press Editions. © 2019 Nicole Eisenman. International Print Center New York is pleased to announce its highly anticipated spring exhibition Pulled In Brooklyn, co-curated by Roberta Waddell and Samantha Rippner, in consultation with printer Luther Davis. This exhibition is the first in-depth exploration of the vibrant network of artists, printers, and workshops that has developed and flourished in Brooklyn since the early 1990s. This monumental exhibition is also IPCNY’s first to occupy two adjacent spaces, -

Grosvenor School Inspired 15 July

PRESS RELEASE Grosvenor School Inspired A group exhibition of contemporary linocuts, inspired by the renowned Grosvenor School of Art style 15 th July – 28 th August 2016 Private view: Thursday 14 th July, 6-8pm Looking ahead for Brook’s Budleigh gallery we are excited to announce the upcoming summer exhibition, Grosvenor School Inspired , featuring artists: Paul Cleden, Lisa Takahashi and Andrew Pavitt. The British Grosvenor School of Modern Art was opened in 1925 by Claude Flight and Iain MacNab. Flight taught the art of lino-cutting and MacNab taught wood engraving. Other teachers included Cyril Power who lectured on architecture, Sybil Andrews as Secretary and Lill Tschudi attended as a young Swiss student. Claude Flight, a former engineer, taught students to produce multi-colour linocut prints by using different blocks for each colour. Flight’s work celebrated the speed, movement and hustle of modern life in the 1920s and 30s, with dominant themes of sport and transport. Many contemporary artists attempt to capture the essence of the Grosvenor School by producing these incredibly complex angular linocuts, few however succeed in the way that Paul Cleden, Lisa Takahashi and Andrew Pavitt do. Their prints notably capture the spirit of the genre whilst putting their own individual styling and nuances into the work. ‘My linocuts are in the tradition of Lill Tschudi, Sybil Andrews and Cyril Power, and more recently Michael Rothenstein and Edward Bawden’, quotes exhibiting artist Paul Cleden. ‘ I love to look at figurative movement; consequently sports are often featured because of the dynamic shapes and action, but equally a crowd of rush hour people leaving a train, or people browsing Dorchester market are wonderful inspiration, whenever I see a crowd my sketchbook twitches.’ Paul is an illustrator, printmaker and writer, originally graduated from London, now lives and works in Dorset. -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

Making 18 01–20 05

artonview art o n v i ew ISSUE No.49 I ssue A U n T U o.49 autumn 2007 M N 2007 N AT ION A L G A LLERY OF LLERY A US T R A LI A The 6th Australian print The story of Australian symposium printmaking 18 01–20 05 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra John Lewin Spotted grossbeak 1803–05 from Birds of New South Wales 1813 (detail) hand-coloured etching National Gallery of Australia, Canberra nga.gov.au InternatIonal GallerIes • australIan prIntmakInG • modern poster 29 June – 16 September 2007 23 December 2006 – 6 May 2007 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra National Gallery of Australia, Canberra George Lambert The white glove 1921 (detail) Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney purchased 1922 photograph: Jenni Carter for AGNSW Grace Crowley Painting 1951 oil on composition board National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 1969 nga.gov.au nga.gov.au artonview contents 2 Director’s foreword Publisher National Gallery of Australia nga.gov.au 5 Development office Editor Jeanie Watson 6 Masterpieces for the Nation appeal 2007 Designer MA@D Communication 8 International Galleries Photography 14 The story of Australian printmaking 1801–2005 Eleni Kypridis Barry Le Lievre Brenton McGeachie 24 Conservation: print soup Steve Nebauer John Tassie 28 Birth of the modern poster Designed and produced in Australia by the National Gallery of Australia 34 George Lambert retrospective: heroes and icons Printed in Australia by Pirion Printers, Canberra 37 Travelling exhibitions artonview ISSN 1323-4552 38 New acquisitions Published quarterly: Issue no. 49, Autumn 2007 © National Gallery of Australia 50 Children’s gallery: Tools and techniques of printmaking Print Post Approved 53 Sculpture Garden Sunday pp255003/00078 All rights reserved. -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

A Uct Ion View

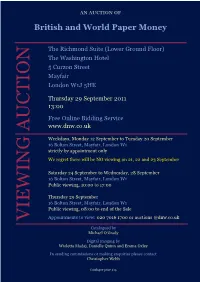

AN AUCTION OF British and World Paper Money The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Thursday 29 September 2011 13:00 Free Online Bidding Service www.dnw.co.uk AUCTION Weekdays, Monday 12 September to Tuesday 20 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 strictly by appointment only We regret there will be NO viewing on 21, 22 and 23 September Saturday 24 September to Wednesday, 28 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Thursday 29 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of the Sale Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or auctions @dnw.co.uk VIEWING Catalogued by Michael O’Grady Digital Imaging by Wioletta Madaj, Danielle Quinn and Emma Oxley In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS Please note: Lots will be sold at a rate of approximately 150 per hour The Sale will be held in one Session starting at 13.00 A Collection of Treasury Notes, the Property of a Gentleman (Part II) ...................................4001-4035 The Celebrated Million Pound Note .........................................................................4036 A Presentation Album to John Benjamin Heath ................................................................................4037 British Banknotes from other properties ..................................................................................4038-4120 The Peter Stanton Collection of Paper Money of Guernsey