Commentaries on the Turner Prize by Leslie Gillon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feral Business Research Network, 2020

RAD- MIN READER Feral Business Research Network, 2020 2020 RADMIN 2O2O Edited by Angela Piccini and Kate Rich ISBN: URL: https://feraltrade.org/radmin/RAD- MIN_READER_2020.pdf Published by Feral Business Research Network in February 2020. This document is copyright of all contributing authors. Some rights reserved. It is published under the CC BY-NC Licence. This licence lets others remix, tweak, and build upon the text in this work for non-commercial purposes. Any new works must also acknowledge the authors and be non-commercial. However, derivative works do not have to be licensed on the same terms. This licence excludes all photographs and images, which have rights reserved to the original artists as listed in this publication. Printing RADMIN READER 2020. DESIGN BY Image: Angela Piccini, University of Bristol LILANI VANE LAST www.vanelast.co.uk 2 RADMIN READER–2O2O 71 CONTENTS P.4 Introduction - Organising Through a RADMIN Lens 1O RADMIN - Call for Festival Participation 12 The Viriconium Palace - ‘The Shares’ a Meal and a Bucket of Money 16 Incidental Unit - W5: Workshop on the Open Brief 28 Common Wallet - Common Wallet: an Experiment in Financial Commoning 34 RADMIN - Budget 36 Minopogon - Working Tasks 44 FoAM - Dark Arts, Grey Areas and Other Contingencies 56 Bristol Co-operative Gym - Upstanding Citizens 6O RADMIN- Raffle 7O Printing Note Image: FoAM Printing RADMIN READER 2019. Image: Kate Rich, University of the West of England (UWE) 7O RADMIN READER–2O2O 3 Organising Feral Business Research Network / through Kate Rich and Angela Piccini a RADMIN lens What is radical admin? We digress. -

Rose Wylie 'Tilt the Horizontal Into a Slant'

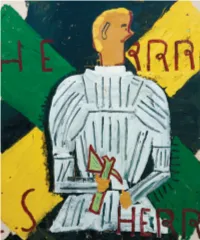

Rose Wylie Tilt The Horizontal Into A Slant 4 TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT 5 INTRO Rose Wylie’s pictures are bold, occasionally chaotic, often unpredictable, and always fiercely independent, without being domineering. Wylie works directly on to large unprimed, unstretched canvases and her inspiration comes from many and varied sources, most of them popular and vernacular. The cutout techniques of collage and the framing devices of film, cartoon strips and Renaissance panels inform her compositions and repeated motifs. Often working from memory, she distils her subjects into succinct observations, using text to give additional emphasis to her recollections. Wylie borrows from first-hand imagery of her everyday life as well as films, newspapers, magazines, and television allowing herself to follow loosely associated trains of thought, often in the initial form of drawings on paper. The ensuing paintings are spontaneous but carefully considered: mixing up ideas and feelings from both external and personal worlds. Rose Wylie favours the particular, not the general; although subjects and meaning are important, the act of focused looking is even more so. Every image is rooted in a specific moment of attention, and while her work is contemporary in terms of its fragmentation and cultural references, it is perhaps more traditional in its commitment to the most fundamental aspects of picturemaking: drawing, colour, and texture. 8 TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT 9 COMING UNSTUCK the power zing back and forth between the painting and us, the viewer? It’s both elegant It may come as a surprise to some, when and inelegant but never either ‘quirky’ or considering Wylie’s work that words like ‘power’ ‘goofy’. -

Artist of the Day 2016 F: +44 (0)20 7439 7733

PRESS RELEASE T: +44 (0)20 7439 7766 ARTIST OF THE DAY 2016 F: +44 (0)20 7439 7733 21 Cork Street 20 June - 2 July 2016 London W1S 3LZ Monday - Friday 11am - 7pm [email protected] Saturday - 11am - 6pm www.flowersgallery.com Flowers Gallery is pleased to announce the 23rd edition of Artist of the Day, a valuable platform for emerging artists since 1983. The two-week exhibition showcases the work of ten artists, nominated by prominent figures in contemporary art. The criteria for selection is talent, originality, promise and the ability to benefit from a one-day solo exhibition of their work at Flowers Gallery, Cork Street. “Every year we look forward to encountering the unknown and unpredictable. The constraint of time to install and promote an exhibition for one day only ensures there is a tangible energy in the gallery, with each day’s show incomparable to the other days. Artist of the Day has given a platform and context to artists who may not have exhibited much before, accompanied by the support and dedication of their selectors. The relationship between the selector and the artist adds an intimate power to the installations, and as a gallery we have gone on to work with many of the selected artists long term.” – Matthew Flowers Past selectors have included Patrick Caulfield, Helen Chadwick, Jake & Dinos Chapman, Tracey Emin, Gilbert & George, Maggi Hambling, Albert Irvin, Cornelia Parker, Bridget Riley and Gavin Turk; while Billy Childish, Adam Dant, Dexter Dalwood, Nicola Hicks, Claerwen James and Seba Kurtis, Untitled, 2015, Lambda C-Type print Lynette Yiadom-Boakye have featured as chosen artists. -

Art and Design Advanced Unit 4: A2 Externally Set Assignment

Pearson Edexcel GCE Art and Design Advanced Unit 4: A2 Externally Set Assignment Timed Examination: 12 hours Paper Reference 6AD04-6CC04 You do not need any other materials. Instructions to Teacher-Examiners Centres will receive this paper in January 2016. It will also be available on the secure content section of the Pearson Edexcel website at this time. This paper should be given to the Teacher–Examiner for confidential reference as soon as it is received in the centre in order to prepare for the externally set assignment. This paper may be released to candidates from 1 February 2016. There is no prescribed time limit for the preparatory study period. The 12-hour timed examination should be the culmination of candidates’ studies. Instructions to Candidates This paper is given to you in advance of the examination so that you can make sufficient preparation. This booklet contains the theme for the Unit 4 Externally Set Assignment for the following specifications: 9AD01 Art, Craft and Design (unendorsed) 9FA01 Fine Art 9TD01 Three-Dimensional Design 9PY01 Photography – Lens and Light-Based Media 9TE01 Textile Design 9GC01 Graphic Communication 9CC01 Critical and Contextual Studies Candidates for all endorsements are advised to read the entire paper. Turn over P46723A ©2016 Pearson Education Ltd. *P46723A* 1/1/1/1/1/1/c2 Each submission for the A2 Externally Set Assignment, whether unendorsed or endorsed, should be based on the theme given in this paper. You are advised to read through the entire paper, as helpful starting points may be found outside your chosen endorsement. If you are entered for an endorsed specification, you should produce work predominantly in your chosen discipline for the Externally Set Assignment. -

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj;Lfdsjlkfdj

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART’S PERFORMANCE EXHIBITION SERIES CONTINUES WITH U.S. PREMIERE OF MARK LECKEY IN THE LONG TAIL Performance 5: Mark Leckey October 1, 2, and 3, 2009, 8:00 p.m. The Abrons Arts Center at the Henry Street Settlement, 466 Grand Street, New York, NY NEW YORK, September 2, 2009—The Museum of Modern Art presents the North American premiere of Mark Leckey in the Long Tail (2009), a performance-based work presented in a theater for performing arts at the Abrons Arts Center on October 1, 2, and 3, 2009, at 8:00 p.m. Throughout the performance—which is part lecture, part monologue, and part living sculpture— Leckey (British, b. 1964) engages the topics of television and broadcasting history, from the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) to the icon of Felix the Cat, while simultaneously addressing the “Long Tail” theory of internet-based economics. Performance 5: Mark Leckey is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator, with Jenny Schlenzka, Assistant Curator for Performance, Department of Media and Performance Art, The Museum of Modern Art. The work made its debut earlier this year at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. Mark Leckey in the Long Tail is a multimedia lecture delivered by the artist in an installation resembling the soundstage of a movie. Incorporating a series of props—a blackboard, a desk, a lectern—the performance involves a live reconstruction of the first television broadcast, with Leckey moving between props and locations throughout. At the start of the lecture Leckey begins at the podium, demonstrating how a doll of Felix the Cat became the first image of the twentieth century transmitted into public consciousness and how, for Leckey, the figure becomes the embodiment of the Long Tail phenomenon of the twenty-first century. -

FRONT DESK / BACK Office

FRONT DESK / BACK OffIce The secret world of galleries in xxx candid pictures and two texts. There’s something not quite the past five years, but allready right about commercial galleries. since the 1990s I look at the They are a kind of schizophrenic back rooms – the other side of space. On the one hand they the art machine – and became explicitly present things with an obsessed by the understatement intellectual and immaterial val- of the façades, the messy, clut- ue, while on the other hand it is tered desks in the small galleries clear that one could eventually and the cold professionalism of possess these things; the expe- the major players’ offices, and, rience has a price tag attached. above all, the uniformity of the They represent two different re- design. They all have the same alities or systems: the discourse MacBooks and iMacs, the same and the market. The discourse desk lamp by Michele de Lucchi is more at home in art institu- and the same designer furniture tions and artist- and curator-run by Charles & Ray Eames, Arne spaces, where looking at art is Jacobsen and Dieter Rams. not corrupted by finance. Selling Have you ever taken a good is, of course, the commercial look at the front desks? It was gallery’s main function, but the at Air de Paris that I first saw a discourse is equally important. gallery position its office partly It is for this reason that looking as a front desk in the midst of and buying are kept apart and the white cube. -

CV 2010! Between Times

Clare Strand CV Born 1973! Living and working in Brighton Uk.! www.clarestrand.co.uk! http://clarestrand.tumblr.com! !www.macdonaldstrand.co.uk.! ! ! Solo Exhibitions! 2015 ! Grimaldi Gavin. london . (Title TBC)! 2014! Further Reading. National Museum Of Krakow. Photomonth, Krakow.! 2013! Arles Discovery Award. Rencontre Arles. France.! 2012! Tacschenspielertrick, Forum Fur Fotografie, Cologne. Germany.! 2011! Sleight, Brancolini Grimaldi Gallery, London.! 2009! Clare Strand Fotographie Und Video, Museum Fur Photograhie Braunschweig,! Germany.! Clare Strand Fotographie Und Video, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany.! 2008! Clare Strand Recent Works, Fotografins Hus, Stockholm Sweden.! 2005! The Betterment Room – Devices for Measuring Achievement, Senko Studio. Denmark.! 2003! Gone Astray, London College of Communication, London.! 2000! Wasted, Galleri Image, Aarhus, Denmark.! 1998! Seeing Red, Museum of Photography Film and Television, Bradford, England; Imago! Festival, Universidad Salamanca, Spain; Viewpoint Gallery, Salford, England and! Royal Photographic Society, Bath England.! 1997! !The Mortuary, F-Stop Gallery, Bath.! ! Group Exhibitions.! 2015! A History of Art, Archetecture, Design from the 1980’s until Today. curated by Christiane Macel. Center Pompidou. Paris France.! European Portraits ( working title) The Centre of Fine Arts, Brussels, Bozor, Nedermands Fotomuseum , Rotterdam and The National Museum of Photography in Thessaloniki .! 2014! (Mis) Understanding Photography, Folkwang Museum, Essen, Germany. Curated by Florian Ebner! -

Artists & Photographs

25_10_11 _ Artists & Photographs Pierre Bergé & associés Société de Ventes Volontaires_agrément n°2002-128 du 04.04.02 12, rue Drouot 75009 Paris T. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 00 F. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 01 Pierre Bergé & associés - Belgique Grand Sablon 40 Grote Zavel Bruxelles B-1000 Brussel T. +32 (0)2 504 80 30 F. +32 (0)2 513 21 65 10, Place Saint-Barthélémy Liège 4000 T. + 32 (0)4 222 26 06 Pierre Bergé & associés - Suisse 11, rue du général Dufour CH-1204 Genève BRUXELLES T. +41 22 737 21 00 F. +41 22 737 21 01 ARTISTS & PHOTOGRAPHS www.pba-auctions.com mardi 25 octobre 2011 1 2 JUST WHAT IS IT THAT MAKES THESE BOOKS SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING ? En 1986, alors étudiant en histoire de l’art à l’Ecole du Louvre, Philippe Nolde découvre « Après une première partie « historique » avec, quelques livres d’artistes de Baldessari au Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, l’exposition, « Fördertürme Chevalements ou Ruscha, une collection des catalogues de la Galerie Sonnabend, nous avons la Mineheads » de Bernd & Hilla Becher. La sérialité et le monde industriel le séduisent. boîte complète d’« Artists & Photographs » édité par Marian Goodman en 1970. Ileana Il retrouve des points communs entre cette œuvre photographique, répétitive et Sonnabend et Marian Goodman sont deux extraordinaires galeries d’art tenues par des typologique, et les musiques industrielles voire les chorégraphies de Trisha Brown, femmes. Une deuxième partie est consacré aux livres et aux œuvres des années ’80 / montrées au Théâtre de la Ville au milieu des années ’80. -

ARTWRITE Diversity In

ARTWRITE INDIA, DiversityARTWRITE PAKISTAN In Art EX. USSR LATIN EXPANSION, 1989 + AMERICA ITING SE IB LE H C X T E I O N N O I V T A A MIDDLE L T I EAST D E A R CIRCUIT OF EXCHANGE MEDIATED T P CENTRE I O R E N T I H N G U O R H T S E R T N E C CHINA AFRICA SOUTH EAST ASIA ARTWRITE: Diversity in Arts ISSN: 1441 - 5712 Special Acknowledgements Jia Guo Joanna Mendelssohn Sub Editor - Ai Weiwei’s Work by Xi Fu Chinese Translation team 4A Gallery PDF Team Museum of Contemporary Art Tamara Dean Yasmin Haas David McNeill Co-Sub Editor - Lupin the Phantom Thief in the Arts: Ruban Nielson (of the Mint Chicks) Banksy by Kim Young-Gu Powerhouse Museum Dr Gene Sherman Edwina Hill Ken and Julia Yonetani Sub Editor - Perpetual Volunteers by Martina Baroncelli Sonic Youth Sub Editor - Benjamin Armstrong by Iris SiYi Shen Gabrielle Wilson Image Captioning team Elinor King Artwrite Team Whip Martina Baroncelli Shanjun Mao Co Editor - For Children Sub Editor - On Censorship: moral panic in art Sub Editor - China and Revolution by Qian Zhao Copywright team Genevieve Barry Chinese Translation Team Sub Editor - A Coming Together of Disparate Forces: career lessons from Dr Gene Sherman by Kim Goodwin Susan Packham Sub Editor - A NSW Aboriginal Art Gallery Sub Editor - What does it mean to be Australian? by Catherine Birrell by Jun Woo Do Sub Editor - Bubble Wrapping Community Arts Sub Editor - Global Warming CAN be Over: by Edwina Hill the art of Ken Yonetani by Vi Girgis Sub Editor - On Censorship: Moral Panic in Art by Qian Zhao Emma Pike Co Editor – Contents -

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 the New Art Large Print Guide

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 12 April – 29 August 2016 The New Art Large Print Guide Please return to exhibition entrance The New Art 1 From 1969 several exhibitions in London and abroad presented conceptual art to wider public view. When Attitudes Become Form at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1969 or Seven Exhibitions at the Tate Gallery in 1972, for example, generated an institutional acceptance and confirmation for conceptual art. It was presented in such exhibitions in different contexts to encompass both an analytical or theoretical conceptual art largely based in language and philosophy, and one that was more inclusive and suggested an expansion of definitions of sculpture. This inclusive view of conceptual art underlines how it was understood as a set of strategies for formulating new approaches to art. One such approach was the increasing use of photography – first as a means of documentation and then recast and conceived as the work itself. Photography also provided a way for sculpture to free itself from objects and re-engage with reality. However, by the mid-1970s some artists were questioning not just the nature of art, but were using conceptual strategies to address what art’s function might be in terms of a social or political purpose. 2 1st Room Wall labels Clockwise from right of wall text John Hilliard born 1945 Camera Recording its Own Condition (7 Apertures, 10 Speeds, 2 Mirrors) 1971 70 photographs, gelatin silver print on paper on card on Perspex Here, Hilliard’s Praktica camera is both subject and object of the work. -

Claire Robins. Curious Lessons in the Museum: the Pedagogic Potential of Artists' Interventions

Bealby, M. S. (2014); Claire Robins. Curious lessons in the museum: the pedagogic potential of artists' interventions. Surrey 2013 Rosetta 16: 42 – 46 http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue16/bealby2.pdf Claire Robins. Curious lessons in the museum: the pedagogic potential of artists' interventions. Surrey, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2013. Pp 260. £65.00. ISBN: 978-1-4094-3617-1 (Hbk). Reviewed by Marsia Sfakianou Bealby University of Birmingham In this publication, Claire Robins discusses art intervention within museums, through a series of 'curious' (in the sense of 'unusual') case-studies - hence the book title. 'Art intervention' is associated with 'conceptual art', i.e. art that stimulates critical thinking beyond traditional aesthetic values. As such, art intervention describes an interaction with a certain space, audience, or previously-existing artwork, in such a manner that their 'normality' is reassessed. A typical example of art intervention - provided by Robins in the introduction - is 'Sandwork' by Andy Goldsworthy.1 A large snake-like feature made from thirty tons of compacted sand, 'Sandwork' was exhibited at the British Museum in 1994, as part of the 'Time Machine' exhibition. The gigantic sculpture aimed at conceptually linking the past (Ancient Egyptian artefacts) with the present (contemporary art). Although there are many memorable examples of artwork provided in her book, it should be underlined that Robins does not merely focus on art. Rather, she places emphasis on the artists who practice art intervention, specifically exploring: i) how artists engage with museum collections through art intervention, ii) how artists contribute to museum education and curation via interventionist artworks, and iii) how art intervention can alter cultural and social 'status-quos' within, and beyond, the museum. -

Michael Craig-Martin B.1941 Untitled, 2000 Acrylic on Canvas 84 X 56 Inches 213.4 X 142.2 Cm

Michael Craig-Martin b.1941 Untitled, 2000 acrylic on canvas 84 x 56 inches 213.4 x 142.2 cm Provenance The Artist WaddingtonGalleries, London Sammlung Froehlich, Stuttgart Exhibitions London, Waddington Galleries, Michael Craig-Martin: Conference, 3May–3 June 2000 (ex-catalogue) Austria, Kunsthaus Bregenz, MichaelCraig-Martin: Signs of Life, 10 June–13 August 2006, illus colour p51 Description ‘My hope in the work is that by bringing certain objects together, you start to see connections, narratives, metaphors between some of them, and then the next one doesn’t fit the pattern, and you have to look again. I try to create as many threads of meaning as possible. But every one of them is at some point denied.’1 Rich with saturated colour, Untitled, 2000 is a striking example of Michael Craig-Martin’s iconic graphic style. Here, on a background of flat, vivid lilac, five seemingly incongruous motifs are united in a playful composition which collapses reference points such as scale, time and space. Craig-Martin first began making line drawings of ordinary objects in 1978 and he has continued this practice ever since. Early drawings were typically made in pencil in an A4 drawing pad, which he would then trace out onto sheets of acetate or drafting film with crepe tape (often black and sometimes red). However in the 1990s, having purchased his first computer, Craig-Martin stopped producing physical drawings, and instead began making them digitally as vector illustrations on a less sophisticated version of CAD, replacing his pencil with a mouse.2 This new method facilitated a greater degree of experimentation, enabling Craig-Martin to play around with the scale of an image, its orientation, colour and the thickness of the line with one click of a button.