The Order of Things: an Archaeology of the Human Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kant's Theoretical Conception Of

KANT’S THEORETICAL CONCEPTION OF GOD Yaron Noam Hoffer Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy, September 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________________ Allen W. Wood, Ph.D. (Chair) _________________________________________ Sandra L. Shapshay, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Timothy O'Connor, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Michel Chaouli, Ph.D 15 September, 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 Yaron Noam Hoffer iii To Mor, who let me make her ends mine and made my ends hers iv Acknowledgments God has never been an important part of my life, growing up in a secular environment. Ironically, only through Kant, the ‘all-destroyer’ of rational theology and champion of enlightenment, I developed an interest in God. I was drawn to Kant’s philosophy since the beginning of my undergraduate studies, thinking that he got something right in many topics, or at least introduced fruitful ways of dealing with them. Early in my Graduate studies I was struck by Kant’s moral argument justifying belief in God’s existence. While I can’t say I was convinced, it somehow resonated with my cautious but inextricable optimism. My appreciation for this argument led me to have a closer look at Kant’s discussion of rational theology and especially his pre-critical writings. From there it was a short step to rediscover early modern metaphysics in general and embark upon the current project. This journey could not have been completed without the intellectual, emotional, and material support I was very fortunate to receive from my teachers, colleagues, friends, and family. -

Rethinking Governmentality

ARTICLE IN PRESS + MODEL Political Geography xx (2006) 1e5 www.elsevier.com/locate/polgeo Rethinking governmentality Stuart Elden* Department of Geography, Durham University, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE, United Kingdom On 1st February 1978 at the Colle`ge de France, Michel Foucault gave the fourth lecture of his course Se´curite´, Territoire, Population [Security, Territory, Population]. This lecture, which became known simply as ‘‘Governmentality’’, was first published in Italian, and then in English in the journal Ideology and Consciousness in 1979. In 1991 it was reprinted in The Foucault Effect, a collection which brought together work by Foucault and those inspired by him (Burch- ell, Gordon, & Miller, 1991). Developing from this single lecture has been a veritable cottage industry of material, across the social sciences, including geography, of ‘governmentality studies’. In late 2004 the full lecture course and the linked course from the following year were pub- lished by Seuil/Gallimard as Se´curite´, Territoire, Population: Cours au Colle`ge de France (1977e1978) and Naissance de la biopolitique: Cours au Colle`ge de France (1978e1979) [The Birth of Biopolitics]. The lectures were edited by Michel Senellart, and the publication was timed to coincide with the 20th anniversary of Foucault’s death. They are currently being translated into English by Graham Burchell, and we publish an excerpt from the first lecture of the Security, Territory, Population course here. Given the interest of geographers in the notion of governmentality, the publication of the lectures is likely to have a significant impact. The concept of governmentality has produced a range of important studies, including those in a range of disciplines (see, for example, Barry, Osborne, & Rose, 1996; Dean, 1999; Lemke, 1997; Senellart, 1995; Walters & Haahr, 2004; Walters & Larner, 2004) as well as some analyses from within geography (Braun, 2000; Cor- bridge, Williams, Srivastava, & Veron, 2005; Hannah, 2000; Huxley, 2007; Legg, 2006). -

HEIDEGGER's TRANSCENDENTALISM Author(S): DANIEL DAHLSTROM Source: Research in Phenomenology, Vol

HEIDEGGER'S TRANSCENDENTALISM Author(s): DANIEL DAHLSTROM Source: Research in Phenomenology, Vol. 35 (2005), pp. 29-54 Published by: Brill Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24721815 Accessed: 23-01-2018 19:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Research in Phenomenology This content downloaded from 142.58.129.109 on Tue, 23 Jan 2018 19:34:17 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms HEIDEGGER S TRANSCENDENTALISM by DANIEL DAHLSTROM Boston University Abstract This paper attempts to marshall some of the evidence of the transcendental character of Heidegger's later thinking, despite his repudiation of any form of transcendental think ing, including that of his own earlier project of fundamental ontology. The transcen dental significance of that early project is first outlined through comparison and contrast with the diverse transcendental turns in the philosophies of Kant and Husserl. The paper then turns to Heidegger's account of the historical source of the notion of tran scendence in Plato's thinking, its legacy in various forms of transcendental philosophy, and his reasons for attempting to think in a post-transcendental way. -

Governing Circulation: a Critique of the Biopolitics of Security

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Governing circulation: A critique of the biopolitics of security Book Section How to cite: Aradau, Claudia and Blanke, Tobias (2010). Governing circulation: A critique of the biopolitics of security. In: de Larrinaga, Miguel and Doucet, Marc G. eds. Security and Global Governmentality: Globalization, Governance and the State. London: Routledge. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2010 Routledge Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415560580/ Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Governing circulation: a critique of the biopolitics of security Claudia Aradau (Open University) and Tobias Blanke (King’s College London) Suggested quotation: Claudia Aradau and Tobias Blanke (2010), ‘Governing Circulation: a critique of the biopolitics of security’ in Miguel de Larrinaga and Marc Doucet (eds), Security and Global Governmentality: Globalization, Power and the State (Basingstoke: Palgrave), pp. 44-58. Michel Foucault’s lectures at the Collège de France on Security, Territory, Population and The Birth of Biopolitics have offered new ways of thinking the transformation of power relations and security practices from the 18 th century on in Europe. While governmental technologies and rationalities had already been aptly explored to understand the multiple ways in which power takes hold of lives to be secured and lives whose riskiness is to be neutralised (e.g. -

Said-Introduction and Chapter 1 of Orientalism

ORIENTALISM Edward W. Said Routledge & Kegan Paul London and Henley 1 First published in 1978 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 39 Store Street, London WCIE 7DD, and Broadway House, Newton Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN Reprinted and first published as a paperback in 1980 Set in Times Roman and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge & Esher © Edward W. Said 1978 No Part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passage in criticism. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Said, Edward W. Orientalism, 1. East – Study and teaching I. Title 950’.07 DS32.8 78-40534 ISBN 0 7100 0040 5 ISBN 0 7100 0555 5 Pbk 2 Grateful acknowledgements is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: Excerpts from Subject of the Day: Being a Selection of Speeches and Writings by George Nathaniel Curzon. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: Excerpts from Revolution in the Middle East and Other Case Studies, proceedings of a seminar, edited by P. J. Vatikiotis. American Jewish Committee: Excerpts from “The Return of Islam” by Bernard Lewis, in Commentary, vol. 61, no. 1 (January 1976).Reprinted from Commentary by permission.Copyright © 1976 by the American Jewish Committee. Basic Books, Inc.: Excerpts from “Renan’s Philological Laboratory” by Edward W. Said, in Art, Politics, and Will: Essarys in Honor of Lionel Trilling, edited by Quentin Anderson et al. Copyright © 1977 by Basic Books, Inc. The Bodley Head and McIntosh & Otis, Inc.: Excerpts from Flaubert in Egypt, translated and edited by Franscis Steegmuller.Reprinted by permission of Francis Steegmuller and The Bodley Head. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Schelling's Organic Form of Philosophy

1 Life as the Schema of Freedom Schelling’s Organic Form of Philosophy ? Subjectivism and the Annihilation of Nature In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the German philosopher F. W. J. Schelling. One major reason for this renewed atten- tion lies in the symphonic power of this thinker’s work, the expanse and complexity of which provides a robust alternative to the anemic theorizing one encounters in contemporary academic philosophy. Too far-reaching to fi t into the categories of either German Idealism or Romanticism, Schelling’s oeuvre is an example of an organic philosophy which, rooted in nature, strives to support the continuous creation of meaning within a unifying and integrated framework. Realizing that the negative force of critique can never satisfy the curiosity of the human spirit, he insists that philosophy must itself be as capable of continuous development as life itself. Advancing such an ambitious project led Schelling to break away from the conceptual current of modern subjectivism to develop a way of doing philosophy fi rmly planted in the sensual world of human experience and nature. For it was only from such an organic standpoint that he believed he would be able to overcome and integrate the dualisms that necessarily follow from modernity’s standpoint of the subject, posited as the otherworldly source of order and form required to regulate the chaotic fl ux of life. As Kant realized, the ideal of unity is the condition of possibility of employing reason systematically. For Schelling, however, Kant failed to pursue the logic of his reasoning to its necessary conclusion, thereby denying continuity between the virtual world of pure reason and the existing reality of nature. -

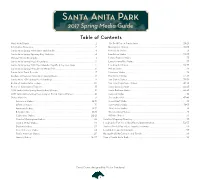

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

The Organization Kid

The Atlantic Monthly | April 2001 THE ORGANIZATION KID The young men and women of America's future elite work their laptops to the bone, rarely question authority, and happily accept their positions at the top of the heap as part of the natural order of life BY DAVID BROOKS few months ago I went to Princeton University to see what the young people who are going to be running our country in a few decades are like. Faculty members gave me the names of a few dozen articulate students, and I sent them e-mails, inviting them out to lunch or dinner in small groups. I would go to sleep in my hotel room at around midnight each night, and when I awoke, my mailbox would be full of replies—sent at 1:15 a.m., 2:59 a.m., 3:23 a.m. In our conversations I would ask the students when they got around to sleeping. One senior told me that she went to bed around two and woke up each morning at seven; she could afford that much rest because she had learned to supplement her full day of work by studying in her sleep. As she was falling asleep she would recite a math problem or a paper topic to herself; she would then sometimes dream about it, and when she woke up, the problem might be solved. I asked several students to describe their daily schedules, and their replies sounded like a session of Future Workaholics of America: crew practice at dawn, classes in the morning, resident-adviser duty, lunch, study groups, classes in the afternoon, tutoring disadvantaged kids in Trenton, a cappella practice, dinner, study, science lab, prayer session, hit the StairMaster, study a few hours more. -

Lepidoptera: Noctuidae, Agaristinae) on Lombok Island (Indonesia) with a Checklist of the Agaristinae of Sumatra, Java, Bali and Lombok (Plate 58) By

Esperiana Band 15: 387-392 Schwanfeld, 12. Januar 2010 ISBN 978-3-938249-10-9 Mimeusemia morinakai KISHIDA, 1995 (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae, Agaristinae) on Lombok Island (Indonesia) with a checklist of the Agaristinae of Sumatra, Java, Bali and Lombok (Plate 58) by Ulf BUCHSBAUM Summary Mimeusemia morinakai KISHIDA, 1995 is recorded for the first time on Lombok Island (Indonesia). The author presents an overview of the collecting site and the collecting methodology. Moreover, a checklist of the Agraristinae of the Sumatra, Java, Bali and Lombok is given. Zusammenfassung Mimeusemia morinakai KISHIDA, 1995 wird erstmals von Lombok (Indonesien) nachgewiesen. Der Autor gibt einen Überblick zum Fundort und beschreibt das Biototop und die Sammelmethodik. Außerdem wird eine Checkliste der Agaristinae der Inseln Sumatra, Java, Bali und Lombok zusammengestellt. key words: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Agaristinae, Mimeusemia morinakai KISHIDA, 1995, biotops, distribution, female genitalia, checklist, Indonesia, Sumatra, Java, Bali, Lombok Introduction Surprisingly very few details about the Insect fauna and especially the Lepidoptera of the Indonesian Islands Bali and Lombok are known. During a trip in December 2003 and January 2004 the author collected on these two islands at various places. In the last years KISHIDA (1992a, 1992b, 1993, 1995, 2000a, 2000b, 2001 & 2003) worked very intensively with Agaristinae and also with the genus Mimeusemia BUTLER, 1875. Some years earlier KIRIAKOFF (1977) published a systematic monography of the Palaearctic and Oriental Agaristinae. Additionally RABENSTEIN & SPEIDEL (1995) reported some details of the life history and biology of some Agaristinae species. It is quite well known that some species of Agaristinae send acoustic contacs and set territoriality signals (ALCOCK et al. -

138904 09 Juvenilefilliesturf.Pdf

breeders’ cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF BREEDERs’ Cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF (GR. I) 6th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR FILLIES, TWO-YEARS-OLD ONE MILE ON THE TURF Weight, 122 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Al Thakhira (GB) Sheikh Joaan Bin Hamad Al Thani Marco Botti B.f.2 Dubawi (IRE) - Dahama (GB) by Green Desert - Bred in Great Britain by Qatar Bloodstock Ltd Chriselliam (IRE) Willie Carson, Miss E. Asprey & Christopher Wright Charles Hills B.f.2 Iffraaj (GB) - Danielli (IRE) by Danehill - Bred in Ireland by Ballylinch Stud Clenor (IRE) Great Friends Stable, Robert Cseplo & Steven Keh Doug O'Neill B.f.2 Oratorio (IRE) - Chantarella (IRE) by Royal Academy - Bred in Ireland by Mrs Lucy Stack Colonel Joan Kathy Harty & Mark DeDomenico, LLC Eoin G. -

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There (The Blackwell

ftoc.indd viii 6/5/10 10:15:56 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/5/10 10:15:35 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Family Guy and Philosophy Kevin Decker Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Heroes and Philosophy The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by David Kyle Johnson Edited by Jason Holt Twilight and Philosophy Lost and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and Edited by Sharon Kaye J. Jeremy Wisnewski 24 and Philosophy Final Fantasy and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Michel S. Beaulieu Battlestar Galactica and Iron Man and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Jason T. Eberl Alice in Wonderland and The Offi ce and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Richard Brian Davis Batman and Philosophy True Blood and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Edited by George Dunn and Robert Arp Rebecca Housel House and Philosophy Mad Men and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Edited by Rod Carveth and Watchman and Philosophy James South Edited by Mark D. White ffirs.indd ii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY WE WANT TO GO TO THERE Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM To pages everywhere .