The Lost World's Pristinity at Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<I>Scutellospora Tepuiensis</I>

MYCOTAXON ISSN (print) 0093-4666 (online) 2154-8889 Mycotaxon, Ltd. ©2017 January–March 2017—Volume 132, pp. 9–18 http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/132.9 Scutellospora tepuiensis sp. nov. from the highland tepuis of Venezuela Zita De Andrade1†, Eduardo Furrazola2 & Gisela Cuenca1* 1 Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas (IVIC), Centro de Ecología, Apartado 20632, Caracas 1020-A, Venezuela 2Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, CITMA, C.P. 11900, Capdevila, Boyeros, La Habana, Cuba * Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract—Examination of soil samples collected from the summit of Sororopán-tepui at La Gran Sabana, Venezuela, revealed an undescribed species of Scutellospora whose spores have an unusual and very complex ornamentation. The new species, named Scutellospora tepuiensis, is the fourth ornamented Scutellospora species described from La Gran Sabana and represents the first report of a glomeromycotan fungus for highland tepuis in the Venezuelan Guayana. Key words—arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, taxonomy, tropical species, Gigasporaceae, Glomeromycetes Introduction The Guayana shield occupies a vast area that extends approximately 1500 km in an east-to-west direction from the coast of Suriname to southwestern Venezuela and adjacent Colombia in South America. This region is mostly characterized by nutrient-poor soils and a flora of notable species richness, high endemism, and diversity of growth forms (Huber 1995). Vast expanses of hard rock (Precambrian quartzite and sandstone) that once covered this area as part of Gondwanaland (Schubert & Huber 1989) have been heavily weathered and fragmented by over a billion years of erosion cycles, leaving behind just a few strikingly isolated mountains (Huber 1995). These table mountains, with their sheer vertical walls and mostly flat summits, are the outstanding physiographic feature of the Venezuelan Guayana (Schubert & Huber 1989). -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Ficha Catalográfica Online

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE BIOLOGIA – IB SUZANA MARIA DOS SANTOS COSTA SYSTEMATIC STUDIES IN CRYPTANGIEAE (CYPERACEAE) ESTUDOS FILOGENÉTICOS E SISTEMÁTICOS EM CRYPTANGIEAE CAMPINAS, SÃO PAULO 2018 SUZANA MARIA DOS SANTOS COSTA SYSTEMATIC STUDIES IN CRYPTANGIEAE (CYPERACEAE) ESTUDOS FILOGENÉTICOS E SISTEMÁTICOS EM CRYPTANGIEAE Thesis presented to the Institute of Biology of the University of Campinas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Plant Biology Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biologia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do Título de Doutora em Biologia Vegetal ESTE ARQUIVO DIGITAL CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA TESE DEFENDIDA PELA ALUNA Suzana Maria dos Santos Costa E ORIENTADA PELA Profa. Maria do Carmo Estanislau do Amaral (UNICAMP) E CO- ORIENTADA pelo Prof. William Wayt Thomas (NYBG). Orientadora: Maria do Carmo Estanislau do Amaral Co-Orientador: William Wayt Thomas CAMPINAS, SÃO PAULO 2018 Agência(s) de fomento e nº(s) de processo(s): CNPq, 142322/2015-6; CAPES Ficha catalográfica Universidade Estadual de Campinas Biblioteca do Instituto de Biologia Mara Janaina de Oliveira - CRB 8/6972 Costa, Suzana Maria dos Santos, 1987- C823s CosSystematic studies in Cryptangieae (Cyperaceae) / Suzana Maria dos Santos Costa. – Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2018. CosOrientador: Maria do Carmo Estanislau do Amaral. CosCoorientador: William Wayt Thomas. CosTese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Biologia. Cos1. Savanas. 2. Campinarana. 3. Campos rupestres. 4. Filogenia - Aspectos moleculares. 5. Cyperaceae. I. Amaral, Maria do Carmo Estanislau do, 1958-. II. Thomas, William Wayt, 1951-. III. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Biologia. IV. Título. -

Why the World's Tallest Waterfall Is Named Angel Falls

terrae incognitae, Vol. 44 No. 1, April, 2012, 16–42 Why the World’s Tallest Waterfall is Named Angel Falls Karen Angel Eureka, California, USA Jimmie Angel (1899–1956) was an aviator and adventurer in the early years of air exploration. This article discusses his discovery of Angel Falls, the world’s tallest waterfall, which bears his name, and the impact of that discovery — and his reputation and dogged determination — on later expeditions into the Venezuelan interior. The author, Angel’s niece, pieces together this fascinating story using a blend of dedicated archival research and painstakingly acquired family history and the reminiscences of friends and acquaintances of Jimmie and his wife Marie. The result is a tale of modern-day exploration and geographic discovery. keywords Jimmie Angel, Angel Falls, Auyántepui, E. Thomas Gilliard, Anne Roe Simpson, George Gaylord Simpson, Venezuela When I began researching the life of American aviator James “Jimmie” Crawford Angel (1899–1956), there were many stories about him in books, newspapers, magazines, and more recently on websites and blogs. Some stories can be verified by the Angel family or other sources; some stories are plausible, but remain unverified; other stories are fabrications. The result is a tangle of true stories and unverified stories. Finding the truth about Jimmie Angel is also complicated because he himself repeated the various unverified stories that became legends about his life.1 As the daughter of Jimmie Angel’s youngest brother Clyde Marshall Angel (1917– 97), I had heard stories about my uncle since childhood, but the family had few documents to support the stories. -

Anura: Dendrobatidae: Anomaloglossus) from the Orinoquian Rainforest, Southern Venezuela

TERMS OF USE This pdf is provided by Magnolia Press for private/research use. Commercial sale or deposition in a public library or website is prohibited. Zootaxa 2413: 37–50 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new dendrobatid frog (Anura: Dendrobatidae: Anomaloglossus) from the Orinoquian rainforest, southern Venezuela CÉSAR L. BARRIO-AMORÓS1,4, JUAN CARLOS SANTOS2 & OLGA JOVANOVIC3 1,4 Fundación AndígenA, Apartado postal 210, 5101-A Mérida, Venezuela 2University of Texas at Austin, Integrative Biology, 1 University Station C0930 Austin TX 78705, USA 3Division of Evolutionary Biology, Technical University of Braunschweig, Spielmannstr 8, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany 4Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract A new species of Anomaloglossus is described from the Venezuelan Guayana; it is the 21st described species of Anomaloglossus from the Guiana Shield, and the 15th from Venezuela. This species inhabits rainforest on granitic substrate on the northwestern edge of the Guiana Shield (Estado Amazonas, Venezuela). The new species is distinguished from congeners by sexual dimorphism, its unique male color pattern (including two bright orange parotoid marks and two orange paracloacal spots on dark brown background), call characteristics and other morphological features. Though to the new species is known only from the northwestern edge of the Guiana Shield, its distribution may be more extensive, as there are no significant biogeographic barriers isolating the type locality from the granitic lowlands of Venezuela. Key words: Amphibia, Dendrobatidae, Anomaloglossus, Venezuela, Guiana Shield Resumen Se describe una nueva especie de Anomaloglossus de la Guayana venezolana, que es la vigesimoprimera descrita del Escudo Guayanés, y la decimoquinta para Venezuela. -

Anura: Dendrobatidae: Colostethus) from Aprada Tepui, Southern Venezuela

Zootaxa 1110: 59–68 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1110 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new dendrobatid frog (Anura: Dendrobatidae: Colostethus) from Aprada tepui, southern Venezuela CÉSAR L. BARRIO-AMORÓS Fundación AndígenA., Apartado postal 210, 5101-A Mérida, Venezuela; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract A new species of Colostethus is described from Venezuelan Guayana. It inhabits the slopes of Aprada tepui, a sandstone table mountain in southern Venezuela. The new species is distinguished from close relatives by its particular pattern, absence of fringes on fingers, presence of a lingual process, and yellow and orange ventral coloration. It is the 18th described species of Colostethus from Venezuelan Guayana. Key words: Amphibia, Dendrobatidae, Colostethus breweri sp. nov., Venezuelan Guayana Introduction In recent years, knowledge of the dendrobatid fauna of the Venezuelan Guayana has increased remarkably. While La Marca (1992) referred four species, Barrio-Amorós et al. (2004) reported 17 species; one more species will appear soon (Barrio-Amorós & Brewer- Carías in press). The discovery of new species has coincided with progressive exploration of the Guiana Shield, one of the most inaccessible and unknown areas in the world. Barrio- Amorós et al. (2004) reviewed the taxonomic history of Colostethus from Venezuelan Guayana. Here, I provide the description of an additional new species from Aprada tepui, situated west of Chimantá massif and Apacara river. This species was collected by Charles Brewer-Carías and colleagues, during ongoing exploration of Venezuelan Guayana. The only known amphibian from the Aprada tepui is Stefania satelles, from 2500 m (Señaris et al. -

Anew Species of the Genus Oreophrynella

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadernos Espinosanos (E-Journal) Volume 45(6):61-67, 2005 A NEW SPECIES OF THE GENUS OREOPHRYNELLA (ANURA; BUFONIDAE) FROM THE GUIANA HIGHLANDS JOSEFA CELSA SEÑARIS1,2 CARLOS DONASCIMIENTO1,3 OSVALDO VILLARREAL1,4 ABSTRACT Oreophrynella weiassipuensis sp. nov. is described from Wei-Assipu-tepui on the Guyana-Brazil border. The new species is distinguished from other species of the genus by the presence of well developed post-orbital crests, toe webbing, dorsal skin minutely granular with scattered large tubercles, and reddish brown dorsal and ventral coloration. KEYWORDS: Anura, Bufonidae, Oreophrynella, new species, Pantepui, Guiana Shield, Guyana, Brazil. INTRODUCTION was described from the summit of Cerro El Sol (Diego-Aransay and Gorzula, 1987), a tepui which is The bufonids of the genus Oreophrynella are a not part of the Roraima formation. Señaris et al. group of noteworthy small toads, endemic to the (1994) reviewed the Guiana highland bufonids and highlands of the Guiana Region in northeastern South described two additional species, O. nigra from America. Members of this genus are frogs of small Kukenán and Yuruaní tepuis, and O. vasquezi from Ilú- size (< 26 mm SVL), characterized by opposable digits tepui. Finally Señaris (1995) described O. cryptica from of the foot, tuberculate dorsal skin, and direct Auyán-tepui. development (McDiarmid, 1971; McDiarmid and On July 2000 a speleological expedition to Wei- Gorzula, 1989; Señaris et al., 1994). Assipu-tepui, conducted by members of the Italian and The genus was created by Boulenger (1895a, b) Venezuelan speleological societies (Carreño et al., 2002; for the newly described species O. -

How to Bring About Forest-Smart Mining: Strategic Entry Points for Institutional Donors

How to bring about forest-smart mining: strategic entry points for institutional donors November 2020 How to bring about forest-smart mining: strategic entry points for institutional donors November 2020 About this report: The World Bank’s PROFOR Trust Fund developed the concept of Forest-Smart Mining in 2017 to raise awareness of different economic sectors’ impacts upon forest health and forest values, such as biodiversity, ecosystem services, human development, supporting and regulating services and cultural values. From 2017 to 2019, Levin Sources, Fauna and Flora International, Swedish Geological AB, and Fairfields Consulting were commissioned by the World Bank/PROFOR Trust fund to investigate good and bad practices of all scales of mining in forest landscapes, and the contextual conditions that support ‘forest-smart’ mining. Three reports and an Executive Summary were published in May 2019, further to a series of events and launches in New York, Geneva, and London which have led to related publications. This report was commissioned by a philanthropic foundation to provide an analysis of the key initiatives and stakeholders working to address the negative impacts of mining on forests. The purpose of the report is to provide a menu of recommendations to inform the development of a new program to bring about forest-smart mining. In the interest of raising awareness and stimulating appetite and action by other institutional donors to step into this space, the client has permitted Levin Sources and Fauna & Flora International to further develop and publish the report. We would like to thank the client for the opportunity to do so. -

Microvegetation on the Top of Mt. Roraima, Venezuela

Fottea 11(1): 171–186, 2011 171 Microvegetation on the top of Mt. Roraima, Venezuela Jan KA š T O V S K Ý 1*, Karolina Fu č í k o v á 2, Tomáš HAUER 1,3 & Markéta Bo h u n i c k á 1 1Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 31, České Budějovice 37005, Czech Republic; *e–mail: [email protected] 2University of Connecticut, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 75 North Eagleville Road, Storrs, CT 06269–3043, U.S.A. 3Institute of Botany of the Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic, Dukelská 135, Třeboň 37982, Czech Republic. Abstract: Venezuelan Table Mountains (tepuis) are among world’s most unique ecological systems and have been shown to have high incidence of endemics. The top of Roraima, the highest Venezuelan tepui, represents an isolated enclave of species without any contact with the surrounding landscape. Daily precipitation enables algae and cyanobacteria to cover the otherwise bare substrate surfaces on the summit in form of a black biofilm. In the present study, 139 samples collected over 4 years from various biotopes (vertical and horizontal moist rock walls, small rock pools, peat bogs, and small streams and waterfalls) were collected and examined for algal diversity and species composition. A very diverse algal flora was recognized in the habitats of the top of Mt. Roraima; 96 Bacillariophyceae, 44 Cyanobacteria including two species new to science, 37 Desmidiales, 5 Zygnematales, 6 Chlorophyta, 1 Klebsormidiales, 1 Rhodophyta, 1 Dinophyta, and 1 Euglenophyta were identified. Crucial part of the total biomass consisted of Cyanobacteria; other significantly represented groups were Zygnematales and Desmidiales. -

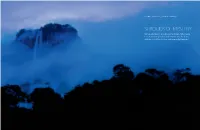

Shrouds of Mystery

Story Giles Foden Photographs Philip Lee Harvey SHROUDS OF MYSTERY Venezuela’s bizarre antediluvian landscape hides many secrets, tempting fearless adventurers over the years with the possibility of riches and even enlightenment The waterfall seemed to fall through eternity. Sifted in the sieve of itself – hovering in the air, staggering but never stopping – it appeared to be part of a world in which time had slowed down, or somehow been canceled altogether. There are verifiable reasons to explain how this impression could form in my head. Water from above was decelerating as it hit water below, water that had itself already slowed down – and so on and on. The phenomenon that is Angel Falls comes down in some of the world’s oldest natural formations: the table- like “tepui” mountains that rise, suddenly and inconceivably, from the Gran Sabana. This vast area of grassland and jungle is the heartland of Venezuela. The tepuis themselves are remnant geological features of Gondwanaland, Myth and legend surround a supercontinent that existed some 180 million years ago, when Africa and South America were conjoined. It was the American pilot Jimmie no wonder I felt out of time. Angel, after whom Angel Falls in Venezuela is Silent and amazed, perched on a rocky outcrop opposite the falls, I watched the cascade’s foaming sections, named. He was born streaming and checking in the roaring flow. At 3,212 feet high, Angel Falls is the world’s tallest waterfall, a “vertical in Missouri in 1899 river” that has mesmerized many before me. With a flash of insight, I realized its movement exemplified humanity’s never-ending Auyántepui, the mountain from which it descends, reads like dance between holism and separation; everything is connected, something out of a novel. -

Reportaje Central Main Article

reportaje central main article 28 www.facesdigital.com La Cueva Charles Brewer Uno de los descubrimientos más importantes de los últimos tiempos según se informa en las publicaciones internacionales. Un regalo de la naturaleza, de dimensiones difíciles de imaginar, encontrado por casualidad, y que hoy es reconocido como la cueva de cuarcita más grande del mundo. International publications have considered it one of the most important discoveries of recent times. A gift of nature, of dimensions which are hard to imagine, found by chance, and that today is recognized as the greatest quartzite cave in the world. Por/By: Alfredo A. Chacón, Javier Mesa y Federico Mayoral Foto/Photo: Marek Audy, Charles Brewer-Carías y Javier Mesa 29 reportaje central main article Ninguno de los exploradores que es- Para revisar los antecedentes al des- tuvo en la Guayana venezolana an- cubrimiento de la extraordinaria tes de 1930 informó haber visto una Cueva Charles Brewer en la cum- of the explor- montaña tan extensa como la Isla bre de ese macizo montañoso que ers who were de Margarita (en Venezuela) o la Isla ahora se llama Chimantá, es preciso in the Vene- Gran Canaria (en España), hasta que remontarnos a enero de 1962, cuan- Nonezuelan Guayana before 1930 informed el explorador Holdridge publicó en do Charles Brewer-Carías regresó to have seen such an extensive mountain N as Margarita Island (in Venezuela) or the 1931 la fotografía de un macizo mon- de dirigir una expedición en la que tañoso de más de 2.000 m. de altura había ido a buscar los restos de la Gran Canaria Island (in Spain), until 1931 al que llamó “Metcalf Mountains”. -

A New GT5 Event in a Previously Aseismic Region of the Brazilian Phanerozoic Parnaiba Basin

A new GT5 event in a previously aseismic region of the Brazilian Phanerozoic Parnaiba Basin. Lucas Barros, Marcelo Assumpção, Marcelo Rocha and Juraci Carvalho T2.3-P1 Figure 6a. – waveform main event The low Brazilian seismicity, with only three Fig. 2 - Ground For hypocentral location an accurate velocity (top) and reference (bottom). Trhuth events continental earthquakes of magnitude five in the model was determined using phase conversion, Figure 6b. – correlation main event and reference. last three decades (Figure 1) and, until recently, clearly identified on the interface sediment- the low number of seismic stations, explain why basement (Figure 5a). it is difficult to detect events at regional In this work, we present a new GT5 event in order Figure 7 – Phase picking correlation of distances that can be classed as Ground True to better define the 3D velocity model for Brazil. eleven events. ROSB Station phase P comp Z. event (GT5). Local velocity model -Components Aftershocks hypocentral location of 7 events with three Z, R and T in VM2, VM4 and VM6. Sp e Ps are phases converted in the stations: VGM2, VGM4 and ROSB) and two events located basement interface x sediments. Ps – P = S – Sp, proportional to the with the addition of VGM5 and VGM6 (Figure 8). thickness of the sediment package Maranhão earthquake of January 3, 2017 – 4.6 mb Figure 5a. – Local network (VI MMI). Detected by 50 stations- 86 phases at Waveform (Ps – P = S – Sp). distances up to 2500 km. 1D Velocity model 3.60 0.00 6.20 0.50 6.40 10.00 8.00 40.00 Hi = 5km Vp/Vs = 1.73 Figure 8 – seven events located with 3 stations and two with 5 stations.