NEP 2020: Implementation Strategies Implementation Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening and Closing Rank of Gujarat Board Candidate -B. Arch ROUND 1

Opening and closing Rank of Gujarat Board candidate -B. Arch ROUND 1 Inst_ Inst_Name Category Opening Closing Code 101 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The M.S.University of Baroda GEN 10003.0 10052.0 101 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The M.S.University of Baroda SEBC 10060.0 10192.0 101 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The M.S.University of Baroda EWSs 10066.0 10088.0 101 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The M.S.University of Baroda SC 10117.0 10277.0 101 Department of Architecture,Faculty of technology & Engineering,The M.S.University of Baroda ST 10220.0 10784.0 102 Faculty of Architecture,CEPT University GEN 10001.0 10053.0 102 Faculty of Architecture,CEPT University EWSs 10058.0 10105.0 102 Faculty of Architecture,CEPT University SEBC 10064.0 10330.0 102 Faculty of Architecture,CEPT University SC 10089.0 10389.0 103 D.C.Patel School of Architecture, Arvindbhai Patel Institute of Environmental Design GEN 10119.0 10558.0 103 D.C.Patel School of Architecture, Arvindbhai Patel Institute of Environmental Design SEBC 10564.0 10793.0 103 D.C.Patel School of Architecture, Arvindbhai Patel Institute of Environmental Design EWSs 10565.0 10639.0 103 D.C.Patel School of Architecture, Arvindbhai Patel Institute of Environmental Design SC 10746.0 10746.0 104 AAERT & SSB, Faculty of Architecture,Sarvajanic college of Engineering & Technology GEN 10028.0 10213.0 104 AAERT & SSB, Faculty of Architecture,Sarvajanic college of -

Seats Vacant Due to Non-Allotment in BE 2020 Round-02

Seats Vacant due to non-allotment in BE 2020 Round-02 Inst_Name Course_name Total Vacant A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING 53 50 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad CIVIL ENGINEERING 27 22 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 27 24 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION ENGG. 27 23 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad FOOD PROCESSING & TECHNOLOGY 53 7 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 79 75 ADANI INSTITUTE OF INFRASTRUCTURE ENGINEERING,AHMEDABAD Civil & Infrastructure Engineering 53 21 ADANI INSTITUTE OF INFRASTRUCTURE ENGINEERING,AHMEDABAD ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 53 37 ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF AERONAUTICAL ENGINEERING 90 82 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING 30 15 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF CIVIL ENGINEERING 30 28 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 60 55 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 111 18 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 90 90 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING 26 25 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad CIVIL ENGINEERING 19 17 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 19 18 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION ENGG. 19 19 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 38 36 Alpha College Of Engg. & Tech., Khatraj, Kalol CIVIL ENGINEERING 75 75 Alpha College Of Engg. -

Admission Committee for Professional Courses Provisional Mba Institute

ADMISSION COMMITTEE FOR PROFESSIONAL COURSES PROVISIONAL MBA INSTITUTE LIST FOR YEAR 2021-22 AS ON 30.06.2021 FEES OF ALL INSTITUTE IS AS PER 2020-21 FEES FOR YEAR 2021-22 MAY BE REVISED. YOU MAY REFER WEBSITE : www.frctech.ac.in P= SFI INSTITUTE; GOVT=GOVERNMENT; GIA=GRANT IN AID W-ONLY FEMALE INSTITUTE TOTAL TOT SEAT SEAT NR FESS OF Type of MQ AL WITH Sr. No. Name of the Institute AFFILIATED UNIVERSITY ADDRESS OF UNIVERSITY AFTER I YEAR 2020- Inst. MQ ACPC EWS 21** Seats as per 2020-21* Ahmedabad Institute of Technology Gota, Ahmedabad (SFI) Beside Vasantnagar Township Gota-Ognaj Road, off Gota Cross Road, GUJARAT TECHNOLOGICAL Ahmedabad-380 060. 1 Ahmedabad Institute of Technology P 67 30 0 30 37 71000 UNIVERSITY Ph. : (02717) 241132 / 241133 Fax : ( 02717) 241132 Email : [email protected] Website: www.aitindia.in Anand Institute of Management, Anand (SFI) GUJARAT TECHNOLOGICAL Shri R K S M Campus, Opp. Town Hall, Anand– 388 001 2 Anand Institute of Management P 67 6 0 6 61 73000 UNIVERSITY Phone / Fax : 02692269977 Email : [email protected] Website:www.aimrksm.org Faculty of Management Studies,Atmiya University Atmiya University, Faculty of Business of Master in Business Administration 3 Commerce (Erstwhile: Atmiya Institute of P ATMIYA UNIVERSITY “Yogidham Gurukul”, Kalawad Road,Rajkot-360 005. 135 60 0 60 75 88000 Technology & Science (MBA) Ph.: 0281-2563445, 0281-2563766 Email : [email protected] Website:www.atmiyauni.net Bhagwan Mahavir College of Management (SFI), Surat New City Light Road, Sr No. 149, Nr. Ashirwad Villa, B/h HeenaBunglows, BHAGWAN MAHAVIR COLLEGE OF BHAGWAN MAHAVIR 4 P BharthanaVesu, Surat. -

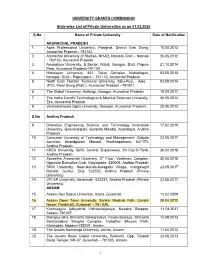

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-Wise List of Private

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-wise List of Private Universities as on 01.02.2020 S.No Name of Private University Date of Notification ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1. Apex Professional University, Pasighat, District East Siang, 10.05.2013 Arunachal Pradesh - 791102. 2. Arunachal University of Studies, NH-52, Namsai, Distt – Namsai 26.05.2012 - 792103, Arunachal Pradesh. 3. Arunodaya University, E-Sector, Nirjuli, Itanagar, Distt. Papum 21.10.2014 Pare, Arunachal Pradesh-791109 4. Himalayan University, 401, Takar Complex, Naharlagun, 03.05.2013 Itanagar, Distt – Papumpare – 791110, Arunachal Pradesh. 5. North East Frontier Technical University, Sibu-Puyi, Aalo 03.09.2014 (PO), West Siang (Distt.), Arunachal Pradesh –791001. 6. The Global University, Hollongi, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 18.09.2017 7. The Indira Gandhi Technological & Medical Sciences University, 26.05.2012 Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. 8. Venkateshwara Open University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 20.06.2012 S.No Andhra Pradesh 9. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation 17.02.2019 University, Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh 10. Centurian University of Technology and Management, Gidijala 23.05.2017 Junction, Anandpuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam- 531173, Andhra Pradesh. 11. KREA University, 5655, Central, Expressway, Sri City-517646, 30.04.2018 Andhra Pradesh 12. Saveetha Amaravati University, 3rd Floor, Vaishnavi Complex, 30.04.2018 Opposite Executive Club, Vijayawada- 520008, Andhra Pradesh 13. SRM University, Neerukonda-Kuragallu Village, mangalagiri 23.05.2017 Mandal, Guntur, Dist- 522502, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 14. VIT-AP University, Amaravati- 522237, Andhra Pradesh (Private 23.05.2017 University) ASSAM 15. Assam Don Bosco University, Azara, Guwahati 12.02.2009 16. Assam Down Town University, Sankar Madhab Path, Gandhi 29.04.2010 Nagar, Panikhaiti, Guwahati – 781 036. -

University Aishe Code

University Aishe Code Aishe Srno Code University Name 1 U-0122 Ahmedabad University (Id: U-0122) 2 U-0830 ANANT NATIONAL UNIVERSITY (Id: U-0830) 3 U-0125 Carlox Teachers University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0125) Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology University, Ahmedabad (Id: U- 4 U-0127 0127) 5 U-0131 Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0131) 6 U-0775 GLS UNIVERSITY (Id: U-0775) 7 U-0135 Gujarat Technological University, Ahmedbabd (Id: U-0135) 8 U-0136 Gujarat University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0136) 9 U-0817 GUJARAT UNIVERSITY OF TRANSPLANTATION SCIENCES (Id: U-0817) 10 U-0137 Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0137) 11 U-0139 Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar (Id: U-0139) 12 U-0922 Indrashil University (Id: U-0922) INSTITUTE OF INFRASTRUCTURE TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT 13 U-0765 (IITRAM) (Id: U-0765) 14 U-0734 LAKULISH YOGA UNIVERSITY, AHMEDABAD (Id: U-0734) 15 U-0146 Nirma University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0146) 16 U-0790 RAI UNIVERSITY (Id: U-0790) 17 U-0595 Rakshashakti University, Gujarat (Id: U-0595) 18 U-0123 Anand Agricultural University, Anand (Id: U-0123) 19 U-0128 Charotar University of Science & Technology, Anand (Id: U-0128) 20 U-0148 Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar (Id: U-0148) 21 U-0150 Sardarkrushinagar Dantiwada Agricultural University, Banaskantha (Id: U-0150) 22 U-0124 Maharaja Krishnakumarsinhji Bhavnagar University (Id: U-0124) 23 U-0126 Central Univeristy of Gujarat, Gandhinagar (Id: U-0126) 24 U-0594 Children University, Gandhinagar (Id: U-0594) Dhirubhai Ambani Institute -

UGTA18 Zones .Xlsx

NATIONAL AWARDS FOR EXECLLENCE IN ARCHITECTURAL THESIS 2018 Zone 01 Sr. No. College Name of College code 1 DL01 School of Planning & Architecture, New Delhi 2 DL03 College of Architecture, Vastu Kala Academy, New Delhi 3DL04Faculty of Architecture & Ekistics, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi 4DL06University School of Architecture & Planning, Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, Delhi 5DL07MBS School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi 6 DL08 K.R.Mangalam School of Architecture & Planning, New Delhi 7HP01Faculty of Architecture, National Institute of Technology, Hamirpur, Haryana 8HP03IEC School of Architecture, Baddi, Himachal Pradesh 9 HP04 Maharaja Agrasen School of Architecture & Design, Maharaja Agrasen University, Baddi, Himachal Pradesh 10 HP05 APG School of Architecture, APG Shimla University, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh 11 HR01 Sushant School of Art & Architecture Ansal University, Gurgaon , Haryana 12 HR02 Department of Architecture, Deenbandhu Chhotu Ram University of Science & Technology, Murthal , Haryana 13 HR03 Gateway College of Architecture & Design, Sonepat , Haryana 14 HR04 Sat Priya School of Architecture and Design, Rohtak, Haryana 15 HR06 School of Architecture R.P. Educational Trust Group of Institutions, Gharaunda Karnal, Haryana 16 HR07 ICL Institute of Architecture and Town Planning, Ambala,01 Haryana 17 HR08 Lingaya’s University’s School of Architecture, Faridabad, Haryana 18 HR09 Om Institute of Architecture & Design, Juglan Hisar, Haryana 19 HR11 Ganga Institute of Architecture & Town Planning, Jhajjar, -

List of Law Colleges Having Deemed / Permanent / Temporary Approval Of

1 College Name & place Courses imparted Status Year of of approval establishment List of Law Colleges having approval of affiliation of the Bar Council of India as on 31st May, 2018 ANDHRA PRADESH College Name & Place Courses imparted Status Year of of approval establishment 1. ANDHRA UNIVERSITY, WALTAIR 1. University Law College , Waltair 3 year course Upto 2010-11 1945 (Dr.B.R. Ambedkar College of Law ) 5 year course(120) Upto2014-2015 2009 (no admission in 5 year course from 2011-12 to 2012-13) 2. Veeravalli College of Law, Rajahmundry 3 year course Upto 2013-14 1995 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1995 3. D.N. Raju Law College, Bhimavaram 3 year course Upto 2011-12 1989 5 year course Upto 2009-10 1989 4. Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Law, Kakinada 3 year course Upto 2014-15 1992 5 year course Upto 2014-15 1992 5. P.S. Raju Law College, Kakinada 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1992 6. M.P.R. Law College, Srikakulam 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1992 7. Shri Shiridi Sai Vidya Parishad Law 3 year course Upto 2013-14 2000 College, Anakapalli 8. M.R.V.R.G.R Law College, 3 year course(180) Upto 2014-15 1986 Viziayanagaram 5 year BA.LLB course Upto 2013-14 1986 9. N. B. M. Law College, Visakhapatnam 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1986 10. N. V. P. Law College, Visakhapatnam 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1980 11. Shri Shiridi Sai Vidya Parishad Law 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2003-04 1998 College, Amalapuram 12. -

List of Beneficiaries Approved Under SHODH Scheme

List of Beneficiaries approved under SHODH Scheme SN STUDENT NAME UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT 1 GARG DIVITA DEVENDRA AHMEDABAD UNIVERSITY LIFE SCIENCES 2 GADESHA VRUNDA AHMEDABAD UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING AND KAMLESH APPLIED SCIENCE 3 JAIN STUTI PRAVEEN AHMEDABAD UNIVERSITY BIOSCIENCES AND RESEARCH LABORATORY 4 ANIYALIYA MANISHA ANAND AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL DHIRUBHAI UNIVERSITY ENTOMOLOGY 5 BALAS DUDABHAI ANAND AGRICULTURAL SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION BHEEKHUBHAI UNIVERSITY ENGINEERING 6 BANSAL SHAILJA ANAND AGRICULTURAL VETERINARY ANATOMY AND RAJENDRA UNIVERSITY HISTOLOGY 7 BHIMANI POOJABEN ANAND AGRICULTURAL AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS CHATURBHAI UNIVERSITY 8 BRIJESH RAJESHBHAI ANAND AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY HUMBAL UNIVERSITY PHARMACOLOGY AND TOXICOLOGY 9 DABHI DHARMESHKUMAR ANAND AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT OF HORTICULTURE MAVJIBHAI UNIVERSITY 10 DHARA RAJENDRAKUMAR ANAND AGRICULTURAL PLANT PATHOLOGY PRAJAPATI UNIVERSITY 11 DHARSHINI M S ANAND AGRICULTURAL GENETICS AND PLANT BREEDING UNIVERSITY 12 DIMPLE VASANT GOR ANAND AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY BIOTECHNOLOGY List of Beneficiaries approved under SHODH Scheme 13 GHADIALI JATINKUMAR ANAND AGRICULTURAL PLANT PHYSIOLOGY JASHVANTBHAI UNIVERSITY 14 GUNDANIYA HIRAL ANAND AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL VINODBHAI UNIVERSITY STATISTICS 15 KALASARIYA NEETA ANAND AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL UKABHAI UNIVERSITY EXTENSION AND COMMUNICATION 16 MAKWANA SANJAYKUMAR ANAND AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT OF AGRONOMY NATVARLAL UNIVERSITY 17 -

Dr. Rahul D. Parikh

Assistant Professor Coordinator - SSIP at NUV Dr. Rahul Parikh School of Science Qualifications BSc, MSc, PhD Ÿ PhD Botany () - The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Thesis Entitled 'Application of tamarindus indica seeds for defluoridation of ground water'. Ÿ MSc Botany () - The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Dissertation entitled 'Regeneration studies on Centella asiatica (L.) Urb.' Ÿ BSc Botany () - The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Contact Details Phone: +-- Email Id: [email protected] Areas of Expertise Phyto-remediation, Plant Ecology, Plant Tissue Culture Profile Dr. Rahul Parikh has joined Navrachana University as Assistant Professor in . Prior to that he worked as Assistant Professor at Shree Swaminarayan College of Science. He did his Ph.D. from The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda on in the field of Metal Biosorption. Lecture Ÿ CSIR NET Lecture conducted on topic 'Stress Physiology' conducted by PG-N-BT-CBC, South Gujarat Awards and Recognition Ÿ Qualified the very prestigious National Eligibility Test (NET) for Lecturer-ship (NET-LS, ) with All India Rank - th, conducted by Council for Scientific & Industrial Research and University Grants Commission (CSIR & UGC), New Delhi, INDIA Ÿ Awarded the nd Prize in Gujarat State in the 'Minaxi-Lalit Science Award Test', a scholarship exam conducted by Gujarat Science Academy, Ahmedabad. () / Courses & Training Received Ÿ Completed an Online Certificate Course on 'Comprehensive Online Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)' conducted by i-Hub and Education Department, Government of Gujarat during July th July to th September Ÿ Completed an Online certificate course on 'Application of Geoinformatics in Ecological Studies' conducted by Indian Institute of Remote Sensing, Dehradun held between th to th July . -

List of Help Centers Courses-Technical

List of Help Centers Courses-Technical મ嫍ુ યમત્રં ી યવુ ા વાવલબં ન યોજના હ쫍ે પ સેꋍટર કો-ઓર્ડીનેટરનો કામકાજના દિવસે અને કચરે ી સમય િરમમયાન જ સપં કક કરવા માટે મવદ્યાર્થીઓ અને વાલીઓન ે નમ્ર મવનતં ી છે. SR. DISTRICT NAME OF HELP CENTERS 1 Ahmedabad R.C.Tech. Inst., Opp. Gujarat HighCourt, S.G.Highway, Ahmedabad. 2 Ahmedabad Govt. Polytechnic, Near Panjrapole,Ambavadi,Ahmedabad. 3 Ahmedabad L.D.College Of Engineering, Opp.Gujarat University,Ahmedabad 4 Ahmedabad Vishwakarma Government EngineeringCollege, Chandkheda 5 Ahmedabad Government Polytechnic for Girls,Navrangpura,Ahmedabad 6 Ahmedabad L.M.College of Pharmacy, Navrangpura 7 Ahmedabad CEPT University, Navragpura 8 Ahmedabad Gujarat Technological University,Chandkheda 9 Ahmedabad Helpdesk Raksha Shakti University 10 Ahmedabad Nirma University, Opp.S.G.V.P, S.GHighway,Ahmedabad 11 Ahmedabad Girls Ploytechnic, Ahmedabad 12 Ahmedabad Sal Institute of pharmacy 13 Ahmedabad A-One Pharmacy College 14 Ahmedabad R. C. Technical Institute, Opp.Gujarat High Court, S G Highway, Sola 15 Ahmedabad Indus University 16 Amreli Dr.J.N.Maheta Government Polytechnic,Bhavnagar Road, Amreli 17 Anand A.R.College of Pharmacy, V.V.NagarM.N.College of Pharmacy, Khambhat 18 Anand M.N.College of Pharmacy, KhambhatCharotar University of Science & 19 Anand Charotar University of Science &Technology, Changa 20 Anand B & B Institute of Technology, VallabhVidhyanagar 21 Anand Birla Vishvakarma Maha Vidhyalaya,Vallabh Vidyanagar 22 Anand Indukaka Ipcowala College of Pharmacy 23 Anand Sardar Vallabhbhai patel Institute of Technology 24 Anand A D Patel Institute of Technology 25 Anand Anand Pharmacy College 26 Anand G H Patel College of Engineering and Technology 27 Anand Madhuben & Bhanubhai Patel Institute of Technology- CVM Universit 28 Anand Indubhai Patel College of Pharmacy & Reserch Center 29 Anand Bhaikaka University 30 Aravali B.M.Shah College of Pharmacy, Modasa 31 Aravali Government EngineeringCollege,,Shamalaji Road, Modasa 32 Banaskantha Government Engg. -

Higher Education

KNOWLEDGE PAPER SERIES HIGHER EDUCATION INSIDE THIS ISSUE PG. 2 Background ESTABLISHMENT OF PG. 3 Type of Universities PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES PG. 4 Procedure to establish a University IN INDIA: GUJARAT PG. 5 VOLUME ONE Key Highlights of Project Report This paper talks about the process of establishment of Private Universities in India PG. 6 with a special focus on the universities in Gujarat. It explains all procedures which are Regulatory Bodies followed in the establishment of the university and the various regulatory bodies of higher education in India recognized by the MHR&D, Government of India. This document is a crisp read to understand in brief the process of university formation. BACKGROUND The Govt. of Gujarat realized that in this era of liberalization and global education, it is germane to attract, encourage and promote the private sector investments in the realm of Higher Education and lay the legislative pathway to establish and incorporate private self-financing Universities in Gujarat. Also, it was the right time to develop and implement a progressive framework that provides for opportunities to deserving private institutions and educational promoters, with relevant and sufficient experience and exposure in the field of higher education, so as to contribute towards the expansion of higher education and research. At that time, many institutions had also approached the In India, "University" means a University state government to allow them to enter in the established or incorporated by or under a field of qualitative higher education of international Central Act, a Provincial Act or a State Act standards and make it available to the students in and includes any such institution as may, the state at their doorsteps. -

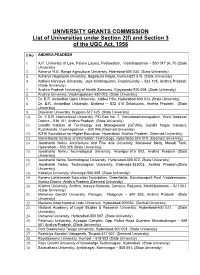

List of Universities Under Section 2(F) and Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION List of Universities under Section 2(f) and Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956 S.No ANDHRA PRADESH 1. A.P. University of Law, Palace Layout, Pedawaltair, Visakhapatnam – 530 017 (A. P) (State University). 2. Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University, Hderabad-500 030. (State University) 3. Acharya Nagarjuna University, Nagarjuna Nagar, Guntur-522 510. (State University) 4. Adikavi Nannaya University, Jaya Krishnapuram, Rajahmundry – 533 105, Andhra Pradesh. (State University) 5. Andhra Pradesh University of Health Sciences, Vijayawada-520 008. (State University) 6. Andhra University, Visakhapatnam-530 003. (State University) 7. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Open University, Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad-500 033. (State University) 8. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University, Etcherla – 532 410 Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh (State University) 9. Dravidian University, Kuppam-517 425. (State University) 10. Dr. Y.S.R. Horticultural University, PO Box No. 7, Venkataramannagudem, West Godavari District – 536 101, Andhra Pradesh. (State University) 11. Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management (GITAM), Gandhi Nagar Campus, Rushikonda, Visakhapatman – 530 045.(Deemed University) 12. ICFAI Foundation for Higher Education, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh. (Deemed University) 13. International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad-500 019. (Deemed University) 14. Jawaharlal Nehru Architecture and Fine Arts University, Mahaveer Marg, Masab Tank, Hyderabad – 500 028 (State University) 15. Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Anantpur-515 002, Andhra Pradesh (State University) 16. Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Hyderabad-500 072. (State University) 17. Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Kakinada-533003, Andhra Pradesh.(State University) 18. Kakatiya University, Warangal-506 009. (State University) 19. Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Greenfields, Kunchanapalli Post, Vaddeswaram, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh (Deemed University) 20.