Nath Sampradaya.FP.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Srimad Bhagawadgita Which Is a Upanisad, Brahma Vidya and Yoga Sastras in the Form of a Dialogue Between Sri Krishna and Arjuna

Newsletter on Bhagavad Gita by Dr. P.V. Nath The following text is a compilation of the single issues of a regular newsletter by e-mail, composed by Dr. Pathikonda Viswambara Nath. It includes the original slokas of the Gita as well as the transliteration, translation and commentaries by Dr. Nath. Copyright to the commentaries on Bhagavad Gita: Dr. P.V. Nath, Great Britain. Inquiries concerning the text please direct to Dr. Nath at "[email protected]". Inquiries concerning the administration of the newsletter and the downloads please direct to [email protected]. To know more about Sri Swamiji, the Sadguru whose blessings made this newsletter possible, please visit: "www.dattapeetham.com" ___________________________________________________________________________ OM SAHA NAVAVATU SAHA NAU BHUNAKTU SAHA VEERYAM KARAVAVAHAI TEJASWI NAVADHEETAMASTU MAA VID VISHAVAHAI May He protect us both (the teacher and the pupil) May He cause us both to enjoy (the Supreme) May we both exert together (to discover the true inner meaning of the scriptures) May our studies be thorough and fruitful. May we never misunderstand each other. ___________________________________________________________________________ The Gita is in the form of dialogue between Krishna, the preceptor and the disciple Arjuna. Sanjaya, the narrator to King Dhritarashtra, intercepts now and then with a comment of his own. There are a total of 18 chapters with 701 verses (slokas.) Each of the chapters has a title and the title ends with the word “Yoga”. The word “Yoga” is derived from the word “Yuj” which means “Unite.” Study of every chapter assists the seeker to unite with the Lord and hence the use of the word “Yoga.” The seeker is he/she who is looking for attaining the union with the “Parabrahman” and experience the “Eternal Bliss.” In Sanskrit the name for the word “seeker” is “Sadhaka”. -

A Translation of the Vijñāna-Bhairava-Tantra (Complete but Lacking Commentary) ©2017 by Christopher Wallis Aka Hareesh

A translation of the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra (complete but lacking commentary) ©2017 by Christopher Wallis aka Hareesh Introductory verse (maṅgala-śloka): “Shiva is also known as ‘Bhairava’ because He brings about the [initial awakening that makes us] cry out in fear of remaining in the dreamstate (bhava-bhaya)—and due to that cry of longing he becomes manifest in the radiant domain of the heart, bestowing absence of fear (abhaya) for those who are terrified. He is also known as Bhairava because he is the Lord of those who delight in his awesome roar (bhīrava), which signals the death of Death! Being the Master of that flock of excellent Yogins who tire of fear and seek release, he is Bhairava—the Supreme, whose form is Consciousness (vijñāna). As the giver of nourishment, he extends his Power throughout the universe!” ~ the great master Rājānaka Kṣemarāja, c. 1020 CE Like most Tantrik scriptures, the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra (c. 850 CE) takes the form of a dialogue between Śiva and Śakti, here called Bhairava and Bhairavī. It begins with the Goddess asking Bhairava: śrutaṃ deva mayā sarvaṃ rudra-yāmala-saṃbhavam | trika-bhedam aśeṣeṇa sārāt sāra-vibhāgaśaḥ || 1 || . 1. O Lord, I have heard the entire teaching of the Trika1 that has arisen from our union, in scriptures of ever greater essentiality, 2. but my doubts have not yet dissolved. What is the true nature of Reality, O Lord? Does it consist of the powers of the mystic alphabet (śabda-rāśi)?2 3. Or, amongst the terrifying forms of Bhairava, is it Navātman?3 Or is it the trinity of śaktis (Parā, Parāparā, and Aparā) that [also] constitute the three ‘heads’ of Triśirobhairava? 4. -

The Pashupatinath Temple Pashupatinath Temple Will Now Be

Om Shri Sai Nathaya Namah: The Pashupatinath Temple will now be seen in Indore With the blessings of almighty Lord Shiva the foundation stone was laid for the building of Shri Sarveshwar Mahadev Temple at Tillor Khurd, Indore, which will be a replica of the ancient and sacred temple of Lord Pashupatinath at Kathmandu, Nepal, along with a Care Home for children with special needs. The ceremony was graced by the presence of revered saints from across the country namely Mahant Shriman Raghumuni Ji (Shi Mahan t, Shri Bada Udasin Akhada), Mahamandaleshwar Guru Sharnanad Ji (Raman Reti - Gokul Mathura), Shri Dahya Bhai Shastri Ji (Nadiad), and political leaders like Shri Kailash Vijayvargiya, Shri Ramesh Mandola, and Shri Jeetu Patwari. The temple being built by the Shiv Om Sai trust about eighteen kilometers from Indore at Tillor Khurd will be exactly like the Pashupatinath Temple from its Architecture, to the other temples of Goddess Mother Annapurna, Vasukinath, Lord Hanuman, Lord Unmat Bhairav and Lord Gane sha that will also be built in the temple complex exactly like in Kathmandu, and also the five faced Holy Lingam. A care home for children with special needs is also being made within the same campus. The main temple will be built on an area of 5500 sq ft and the care home over an area of 25,000 sq ft, with the total campus being spread over an area of 90,000 sq ft. The inspiration for building the temple came one Monday during the month of Shravan in 2014 when, during Shiva puja , one of Guruji’s (founder of the Shiv Om Sai Trust, Shri Manoj Thakkar Ji) disciples mentioned to Guruji that, many years back when he had fallen seriously ill, his father had promised to establish a temple of Lord Shiva along with his family if his health improved; he had gotten better since but the promise remained unfulfilled yet. -

Essays and Addresses on the Śākta Tantra-Śāstra

ŚAKTI AND ŚĀKTA ESSAYS AND ADDRESSES ON THE ŚĀKTA TANTRAŚĀSTRA BY SIR JOHN WOODROFFE THIRD EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED Celephaïs Press Ulthar - Sarkomand - Inquanok – Leeds 2009 First published London: Luzac & co., 1918. Second edition, revised and englarged, London: Luzac and Madras: Ganesh & co., 1919. Third edition, further revised and enlarged, Ganesh / Luzac, 1929; many reprints. This electronic edition issued by Celephaïs Press, somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, and mani(n)fested in the waking world in Leeds, England in the year 2009 of the common error. This work is in the public domain. Release 0.95—06.02.2009 May need furthur proof reading. Please report errors to [email protected] citing release number or revision date. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. HIS edition has been revised and corrected throughout, T and additions have been made to some of the original Chapters. Appendix I of the last edition has been made a new Chapter (VII) in the book, and the former Appendix II has now been attached to Chapter IV. The book has moreover been very considerably enlarged by the addition of eleven new Chapters. New also are the Appendices. The first contains two lectures given by me in French, in 1917, before the Societé Artistique et Literaire Francaise de Calcutta, of which Society Lady Woodroffe was one of the Founders and President. The second represents the sub- stance (published in the French Journal “Le Lotus bleu”) of two lectures I gave in Paris, in the year 1921, before the French Theosophical Society (October 5) and at the Musée Guimet (October 6) at the instance of L’Association Fran- caise des amis de L’Orient. -

Swaroop Sampradaya 1 ______

The Swaroop Sampradaya 1 _______________________________________________________________________________________ The Swaroop Sampradaya Akkalkot Niwasi Shree Swami Samarth “This book attempts to showcase the life of the exalted masters of the Swaroop Sampradaya and gives a brief outlook of the tremendous humanitarian work undertaken by the followers of this sect for the spiritual and material upliftment of the common man” The Swaroop Sampradaya 2 _______________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright 2003 Shree Vitthalrao Joshi charities Trust First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or transmitted by any means - electronic or otherwise -- including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the express permission in writing from: Shree Vitthalrao Joshi Charities Trust, C-28, 'Suyash'/ 'Parijat', 2nd Floor, Near Amar Hind Mandal, Gokhale Road (North), Dadar (West), Mumbai, Pin Code: 400 028, Maharashtra State, INDIA. Shree Vitthalrao Joshi Charities Trust The Swaroop Sampradaya 3 _______________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Swaroop-Sampradaya........................................................................................................... 5 Lord Dattatreya..................................................................................................................... 6 Shrimad Nrusimha Saraswati - Incarnation of Lord Dattareya .......................................... -

Aesthetic Philosophy of Abhina V Agupt A

AESTHETIC PHILOSOPHY OF ABHINA V AGUPT A Dr. Kailash Pati Mishra Department o f Philosophy & Religion Bañaras Hindu University Varanasi-5 2006 Kala Prakashan Varanasi All Rights Reserved By the Author First Edition 2006 ISBN: 81-87566-91-1 Price : Rs. 400.00 Published by Kala Prakashan B. 33/33-A, New Saket Colony, B.H.U., Varanasi-221005 Composing by M/s. Sarita Computers, D. 56/48-A, Aurangabad, Varanasi. To my teacher Prof. Kamalakar Mishra Preface It can not be said categorically that Abhinavagupta propounded his aesthetic theories to support or to prove his Tantric philosophy but it can be said definitely that he expounded his aesthetic philoso phy in light of his Tantric philosophy. Tantrism is non-dualistic as it holds the existence of one Reality, the Consciousness. This one Reality, the consciousness, is manifesting itself in the various forms of knower and known. According to Tantrism the whole world of manifestation is manifesting out of itself (consciousness) and is mainfesting in itself. The whole process of creation and dissolution occurs within the nature of consciousness. In the same way he has propounded Rasadvaita Darsana, the Non-dualistic Philosophy of Aesthetics. The Rasa, the aesthetic experience, lies in the conscious ness, is experienced by the consciousness and in a way it itself is experiencing state of consciousness: As in Tantric metaphysics, one Tattva, Siva, manifests itself in the forms of other tattvas, so the one Rasa, the Santa rasa, assumes the forms of other rasas and finally dissolves in itself. Tantrism is Absolute idealism in its world-view and epistemology. -

Devotional Practices (Part -1)

Devotional Practices (Part -1) Hare Krishna Sunday School International Society for Krishna Consciousness Founder Acarya : His Divine Grace AC. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Price : $4 Name _ Class _ Devotional Practices ( Part - 1) Compiled By : Tapasvini devi dasi Vasantaranjani devi dasi Vishnu das Art Work By: Mahahari das & Jay Baldeva das Hare Krishna Sunday School , , ,-:: . :', . • '> ,'';- ',' "j",.v'. "'.~~ " ""'... ,. A." \'" , ."" ~ .. This book is dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder acarya ofthe Hare Krishna Movement. He taught /IS how to perform pure devotional service unto the lotus feet of Sri Sri Radha & Krishna. Contents Lesson Page No. l. Chanting Hare Krishna 1 2. Wearing Tilak 13 3. Vaisnava Dress and Appearance 28 4. Deity Worship 32 5. Offering Arati 41 6. Offering Obeisances 46 Lesson 1 Chanting Hare Krishna A. Introduction Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu, an incarnation ofKrishna who appeared 500 years ago, taught the easiest method for self-realization - chanting the Hare Krishna Maha-mantra. Hare Krishna Hare Krishna '. Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rams Rams Rama Hare Hare if' ,. These sixteen words make up the Maha-mantra. Maha means "great." Mantra means "a sound vibration that relieves the mind of all anxieties". We chant this mantra every day, but why? B. Chanting is the recommended process for this age. As you know, there are four different ages: Satya-yuga, Treta-yuga, Dvapara-yuga and Kali-yuga. People in Satya yuga lived for almost 100,000 years whereas in Kali-yuga they live for 100 years at best. In each age there is a different process for self realization or understanding God . -

Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism

Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES HANDBUCH DER ORIENTALISTIK SECTION TWO INDIA edited by J. Bronkhorst A. Malinar VOLUME 22/5 Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Volume V: Religious Symbols Hinduism and Migration: Contemporary Communities outside South Asia Some Modern Religious Groups and Teachers Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen (Editor-in-Chief ) Associate Editors Helene Basu Angelika Malinar Vasudha Narayanan Leiden • boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brill’s encyclopedia of Hinduism / edited by Knut A. Jacobsen (editor-in-chief); associate editors, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar, Vasudha Narayanan. p. cm. — (Handbook of oriental studies. Section three, India, ISSN 0169-9377; v. 22/5) ISBN 978-90-04-17896-0 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Hinduism—Encyclopedias. I. Jacobsen, Knut A., 1956- II. Basu, Helene. III. Malinar, Angelika. IV. Narayanan, Vasudha. BL1105.B75 2009 294.503—dc22 2009023320 ISSN 0169-9377 ISBN 978 90 04 17896 0 Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. Printed in the Netherlands Table of Contents, Volume V Prelims Preface .............................................................................................................................................. -

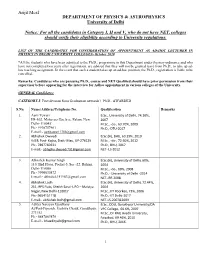

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT of PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS University of Delhi Notice: For all the candidates in Category I, II and V, who do not have NET, colleges should verify their eligibility according to University regulations. LIST OF THE CANDIDATES FOR CONSIDERATION OF APPOINTMENT AS AD-HOC LECTURER IN PHYSICS IN DELHI UNIVERSITY COLLEGES- October 2020 *All the students who have been admitted to the Ph.D., programme in this Department under the new ordinance and who have not completed two years after registration, are advised that they will not be granted leave from Ph.D., to take up ad- hoc teaching assignment. In the event that such a student takes up an ad-hoc position, the Ph.D., registration is liable to be cancelled. Remarks: Candidates who are pursuing Ph.D., course and NET Qualified should have prior permission from their supervisor before appearing for the interview for Adhoc appointment in various colleges of the University. GENERAL Candidates: CATEGORY-I: First division from Graduation onwards + Ph.D., AWARDED S.No. Name/Address/Telephone No. Qualification Remarks 1. Aarti Tewari B.Sc., University of Delhi, 74.10%, H4-102, Mahaveer Enclave, Palam, New 2007 Delhi-110045` M.Sc., -do-, 63.70%, 2009 Ph:- 9910757461 Ph.D.,-DTU-2017 E-mail:- [email protected] 2. Abhishek Dwivedi B.Sc.(H), BHU, 60.39%, 2010 Vill & Post- Kajha, Distt- Mau, UP-276129 M.Sc., -do-, 72.60%, 2012 Ph:- 7897760331 Ph.D., BHU, 2017 E-mail:- [email protected] NET- LS-2012 3. Abhishek Kumar Singh B.Sc.(H), University of Delhi, 60%, 110, IInd Floor, Pocket-5, Sec.-22, Rohini, 2004 Delhi-110086 M.Sc., -do-, 60%, 2008 Ph:- 9990030872 Ph.D.,- University of Delhi -2014 E-mail:- [email protected] NET-JRF-2008 4. -

The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Gokarneshwor

THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE OF GOKARNESHWOR A Thesis Submitted To Central Department of Nepalese History, Culture and Archaeology (NeHCA), Tribhuwan University In the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in Art (MA) Submitted By: Nittam Subedi TU Registration No: 7-2-357-17-2009 Kirtipur, Kathmandu 2016 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The thesis on “The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Gokarneshwor” is written for the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Nepalese History Culture and Archaeology under the Department of Culture, Tribhuvan University. I hereby like to thank to my respected teachers and all those individual as well as institution for their help and support in whatever capacity possible. First of all, I would like to pay my special thanks to Professor Ms. Sabitree Mainali- the Head of Department of NeHCA, Central Department of Tribhuvan University for providing Professor Mr. Madan Rimal, as my thesis guide, who have help me to complete my thesis on time without any hassles. Meantime, I am also grateful to Professor Dr. Ms. Beena Ghimire (Poudel) for her infinite support to complete my thesis. I am also thankful to all my teachers and administration who help me to gather important information related to my thesis topic. I would like to express my indebtedness to my father Mr. Dhurba Bdr. Subedi who have introduce me the respectable person at Gokarneshwor. Also, I express my due respect to Mr. Keshab Bhatta- priest of Gokarneshwor temple; Mr. Nabaraj Poudel- member of Kal Mochan Guthi; Narayan Kaji Shrestha and Sanu Kaji Shrestha-members of Kanti Bhairav Guthi.