Assessing the Extent of Occurrence, Area of Occupancy, Territory Size, and Population Size of Marsh Tapaculo (Scytalopus Iraiensis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programa Federativo De Enfrentamento Ao Coronavírus No Estado De Santa Catarina

+ Programa Federativo de Enfrentamento ao Coronavírus no Estado de Santa Catarina Os valores destinados ao Estado de Santa Catarina, decorrentes da distribuição estabelecida nos termos do Programa Federativo de Enfrentamento ao Coronavírus, são os seguintes: - dentre os recursos a serem aplicados na área de saúde pública: - R$ 219 milhões para o Estado, conforme critérios de população e incidência de COVID-19*; - R$ 102 milhões para os Municípios, conforme critério populacional; - R$ 1,151 bilhões de livre aplicação, pertencentes ao Estado; - R$ 780 milhões de livre aplicação, pertencentes aos Municípios; - R$ 724 milhões pela suspensão no pagamento da dívida* com organismos internacionais e com a União, incluindo dívidas do Estado e dos respectivos Municípios. O total é de R$ 2,977 bilhões, mas além desses valores ainda é necessário somar a eventual dívida com bancos privados. *Observação: os dados relativos à suspensão de dívidas foram fornecidos pelo Ministério da Economia, e os referentes à incidência de COVID-19 em 29/04/2020, pelo Ministério da Saúde. % Recebido Auxílio Recebido pelo Pop. Estimada UF Município pelo Município [IBGE] Município (total nacional de 20+3bi) SC Abdon Batista 2.563 0,04% R$ 315.439,22 SC Abelardo Luz 17.904 0,25% R$ 2.203.520,80 SC Agrolândia 10.864 0,15% R$ 1.337.078,30 SC Agronômica 5.448 0,08% R$ 670.508,34 SC Água Doce 7.145 0,10% R$ 879.365,29 SC Águas de Chapecó 6.486 0,09% R$ 798.259,38 SC Águas Frias 2.366 0,03% R$ 291.193,60 SC Águas Mornas 6.469 0,09% R$ 796.167,12 SC Alfredo Wagner 10.036 0,14% -

Statkraft AS Corporate Responsibility Report 2017 CONTENT

Statkraft AS Corporate Responsibility Report 2017 CONTENT 4 Statkraft around the world 5 Letter from the CEO 6 Statkraft’s contribution 7 Management of corporate responsibility 10 Material topics 11 Social disclosures Health, safety and security Human rights Labour practices 19 Environmental disclosures UN Sustainable Development Goals Biodiversity 23 Economic disclosures Water management Climate change Business ethics APPENDIX 32 About the Corporate Responsibility Report 33 Corporate responsibility statement Social disclosures Environmental disclosures Economic disclosures 45 GRI index 49 UN Global Compact index 50 Auditor’s statement Statkraft around the world TOTAL NUMBER OF POWER PLANTS/ STATKRAFT’S CAPACITY (PRO-RATA) SYMBOLS: FACILITIES (PRO-RATA) = Hydropower Power Power = Wind power generation 353 generation 19 080 MW = Gas power District District = Bio power heating 17 heating 789 MW = District heating =Trading and origination NORWAY 13 769 MW SWEDEN 1 977 MW THE NETHERLANDS UK 152 MW GERMANY 2 694 MW FRANCE TURKEY 122 MW USA San Francisco ALBANIA 72 MW NEPAL 34 MW BULGARIA SERBIA INDIA 136 MW PERU 442 MW BRAZIL 257 MW CHILE 213 MW Since the founding of the company in 1895, Statkraft has The Group’s 353 power plants have a total installed capacity of developed from a national company, focused on developing 19 080 MW (Statkraft’s share). Hydropower is still the dominant Norwegian hydro power resources, into an international company technology, followed by natural gas and wind power. Most of the diversifying also into other sources of renewable energy. Today, installed capacity is in Norway. Statkraft also owns shares in with a total consolidated power generation of 63 TWh in 2017, 17 district heating facilities in Norway and Sweden with a total Statkraft is the second largest power generator in the Nordics and installed capacity of 789 MW. -

Santa Catarina

SEBRAE UF UNIDADE TELEFONE SC Gerência de Desenvolvimento Regional (48) 3221-0843 CAIXA ECONÔMICA FEDERAL COD. IBGE NOME MUNÍCIPIO UF SUPERINTENDÊNCIA EXECUTIVA DO GOVERNO FEDERAL DDD TELEFONE 4200606 MUNICIPIO DE AGUAS MORNAS SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4200903 MUNICIPIO DE ANGELINA SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4201307 MUNICIPIO DE ARAQUARI SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4201505 MUNICIPIO DE ARMAZEM SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4201802 MUNICIPIO DE ATALANTA SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4201901 MUNICIPIO DE AURORA SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4202008 MUNICIPIO DE BALNEARIO CAMBORIU SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4202206 MUNICIPIO DE BENEDITO NOVO SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4202800 MUNICIPIO DE BRACO DO NORTE SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4203204 MUNICIPIO DE CAMBORIU SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4203956 MUNICIPIO DE CAPIVARI DE BAIXO SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4204251 MUNICIPIO DE COCAL DO SUL SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva de Governo FLORIANOPOLIS, SC 48 37225050 4205191 MUNICIPIO DE ERMO SC SEG - Superitendência Executiva -

Plano De Ação Regional De Educação Permanente Em Saúde

Comissão de Integração Ensino-Serviço – CIES Região do Alto Vale do Rio do Peixe PLANO DE AÇÃO REGIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO PERMANENTE EM SAÚDE PAREPS 2019 - 2022 Fevereiro/2019 1 Equipe Responsável pela Elaboração do PAREPS 2015-2018 ELISABETH AP. FRANÇA DACOL – CIES Curitibanos MARJURI PAULA SGARBOSSA – CIES Caçador RICARDO BURATTO – CIES Videira SALIMARA CLAIR MOLIM – CIES Fraiburgo Equipe Responsável pela Atualização do PAREPS 2019-2022 JUCELAINE CRISTINA DOS SANTOS – CIES Curitibanos SALIMARA CLAIR MOLIM – CIES Fraiburgo Fevereiro/2019 2 SUMÁRIO Apresentação 04 1. Introdução 05 2. Objetivos 06 3. Identificação da Região de Saúde 07 4. Consórcio Intermunicipal de Saúde 13 5. Economia da Região 15 6. Perfil Epidemiológico da Região 16 7. Atenção Básica 44 8. Média e Alta Complexidade Ambulatorial 48 9. Atenção Psicossocial 53 10. Urgência/Emergência 54 11. Atenção Hospitalar 56 12. Instituições de Longa Permanência 58 13. Central de Regulação de Leitos 59 14. Ações Desenvolvidas com Recursos da Política Nacional de EPS 60 15. Diagnóstico das Necessidades de Educação Permanente em Saúde 70 16. Recursos da Educação Permanente em Saúde 73 17. Considerações Finais 74 18. Referências 75 3 APRESENTAÇÃO A CIES do Alto Vale do Rio do Peixe apresenta neste documento o Plano de Ação Regional de Educação Permanente em Saúde – PAREPS. O PAREPS foi elaborado em conformidade com a Portaria GM/MS nº. 1.996, de 20 de agosto de 2007 e a partir das discussões entre a CIES e a CIR sobre as demandas levantadas pelos municípios para a definição dos principais desafios na área da saúde pública da região e as intervenções necessárias no campo da educação permanente em saúde. -

Birds of Brazil

BIRDS OF BRAZIL - MP3 SOUND COLLECTION version 2.0 List of recordings 0001 1 Greater Rhea 1 Song 0:17 Rhea americana (20/7/2005, Chapada dos Guimaraes, Mato Grosso, Brazil, 15.20S,55.50W) © Peter Boesman 0006 1 Gray Tinamou 1 Song 0:43 Tinamus tao (15/8/2007 18:30h, Nirgua area, San Felipe, Venezuela, 10.15N,68.30W) © Peter Boesman 0006 2 Gray Tinamou 2 Song 0:24 Tinamus tao (2/1/2008 17:15h, Tarapoto tunnel road, San Martín, Peru, 06.25S,76.15W) © Peter Boesman 0006 3 Gray Tinamou 3 Whistle 0:09 Tinamus tao (15/8/2007 18:30h, Nirgua area, San Felipe, Venezuela, 10.15N,68.30W) © Peter Boesman 0007 1 Solitary Tinamou 1 Song () 0:05 Tinamus solitarius (11/8/2004 08:00h, Serra da Graciosa, Paraná, Brazil, 25.20S,48.55W) © Peter Boesman. 0009 1 Great Tinamou 1 Song 1:31 Tinamus major (3/1/2008 18:45h, Morro de Calzada, San Martín, Peru, 06.00S,77.05W) © Peter Boesman 0009 2 Great Tinamou 2 Song 0:31 Tinamus major (28/7/2009 18:00h, Pantiacolla Lodge, Madre de Dios, Peru, 12.39S,71.14W) © Peter Boesman 0009 3 Great Tinamou 3 Song 0:27 Tinamus major (26/7/2009 17:00h, Pantiacolla Lodge, Madre de Dios, Peru, 12.39S,71.14W) © Peter Boesman 0009 4 Great Tinamou 4 Song 0:46 Tinamus major (22nd July 2010 17h00, ACTS Explornapo, Loreto, Peru, 120 m. 3°10' S, 72°55' W). (Background: Thrush-like Antpitta, Elegant Woodcreeper). © Peter Boesman. 0009 5 Great Tinamou 5 Call 0:11 Tinamus major (17/7/2006 17:30h, Iracema falls, Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas, Brazil, 02.00S,60.00W) © Peter Boesman. -

11 De Junho De 2020

11 de junho de 2020 12.953 8.522 180,8 casos confirmados recuperados casos por 100 mil hab. 186 4.245 1,44% óbitos casos ativos letalidade EVOLUÇÃO DOS CASOS CONFIRMADOS EM SANTA CATARINA EVOLUÇÃO DOS ÓBITOS EM SANTA CATARINA TESTES REALIZADOS 42.702 15.317 540 1.845 PCR testes clínico exames aguardando rápidos epidemiológicos resultado (Lacen) DETALHAMENTO DOS CASOS CONFIRMADOS E ÓBITOS DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE CASOS POR MUNICÍPIO 238 municípios com casos confirmados DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE ÓBITOS POR MUNICÍPIO 64 municípios com óbitos registrados CASOS CONFIRMADOS POR MACRORREGIÃO DE SAÚDE 1357 Planalto Norte e Nordeste 2366 2298 Grande Oeste 1391 Foz do Vale do Rio Itajaí 2021 Itajaí Meio Oeste e Serra Catarinense 1655 Grande 194 Florianópolis Outros estados 2 Outros países 1669 Sul ÓBITOS POR MACRORREGIÃO DE SAÚDE 36 Planalto Norte e Nordeste 28 41 16 Grande Oeste Foz do Vale do Itajaí Rio Itajaí 16 Meio Oeste e Serra Catarinense 18 Grande Florianópolis 31 Sul CASOS E ÓBITOS POR MUNICÍPIO E MACRORREGIÃO DE SAÚDE GRANDE FLORIANÓPOLIS 1655 18 - Gaspar 65 2 - Águas Mornas 3 - Guabiruba 7 1 - Alfredo Wagner - Ibirama 10 - Angelina - Imbuia 1 - Anitápolis - Indaial 87 2 - Antônio Carlos 31 4 - Ituporanga 10 1 - Biguaçu 75 - José Boiteux - Canelinha 22 - Laurentino 3 - Florianópolis 880 9 - Lontras 1 - Garopaba 6 1 - Mirim Doce 1 - Governador Celso Ramos 39 - Petrolândia 1 - Leoberto Leal - Pomerode 25 - Major Gercino - Pouso Redondo 4 1 - Nova Trento 10 - Presidente Getúlio 5 - Palhoça 291 1 - Presidente Nereu - Paulo Lopes 2 - Rio do Campo - Rancho Queimado -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Curitibanos Em Dados Socioeconômicos – 2019/2020

ORGANIZAÇÃO Argos Gumbowsky Maria Luiza Milani Daniela Pedrassani Alexandre Assis Tomporoski Andressa Carla Metzger Jacir Favretto Jairo Marchesan Sandro Luiz Bazzanella Valdir Roque Dallabrida CURITIBANOS EM DADOS SOCIOECONÔMICOS – 2019/2020 2020 CURITIBANOS EM DADOS SOCIOECONÔMICOS – 2019/2020 PARCERIAS Universidade do Contestado – UnC Associação Empresarial de Curitibanos – ACIC Câmara de Diretores Lojistas - CDL ORGANIZAÇÃO EDITORAÇÃO Argos Gumbowsky Camila Candeia Paz Fachi Maria Luiza Milani Elisete Ana Barp Daniela Pedrassani Gabriel Bonetto Bampi Alexandre Assis Tomporoski Gabriela Bueno Andressa Carla Metzger Janice Beker Jacir Favretto Josiane Liebl Miranda Jairo Marchesan Solange Salete Sprandel da Silva Sandro Luiz Bazzanella Valdir Roque Dallabrida Catalogação na fonte – Biblioteca Universitária Universidade do Contestado (UnC) 338.98164 Curitibanos em dados socioeconômicos : 2019/2020 [recurso C975 eletrônico] / Universidade do Contestado ; organização Argos Gumbowsky ... [et al.]. – Mafra, SC : Ed. da UnC, 2020. 86 f. Bibliografia: p. 83-86 ISBN: 978-65-88712-02-3 1. Desenvolvimento econômico – Curitibanos (SC). 2. Curitibanos (SC) – Condições econômicas I. Gumbowsky, Argos (Org.). II. Universidade do Contestado (UnC). III. Título. Bibliotecária: Josiane Liebl Miranda CRB 14/1023 UNIVERSIDADE DO CONTESTADO – UnC SOLANGE SALETE SPRANDEL DA SILVA Reitora LUCIANO BENDLIN Vice-Reitor FUNDAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE DO CONTESTADO – FUnC ISMAEL CARVALHO Presidente ORGANIZAÇÃO Argos Gumbowsky Maria Luiza Milani Daniela Pedrassani Alexandre -

List of References for Avian Distributional Database

List of references for avian distributional database Aastrup,P. and Boertmann,D. (2009.) Biologiske beskyttelsesområder i nationalparkområdet, Nord- og Østgrønland. Faglig rapport fra DMU. Aarhus Universitet. Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser. Pp. 1-92. Accordi,I.A. and Barcellos,A. (2006). Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia. 14:(2): 101-115. Accordi,I.A. (2002). New records of the Sickle-winged Nightjar, Eleothreptus anomalus (Caprimulgidae), from a Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil wetland. Ararajuba. 10:(2): 227-230. Acosta,J.C. and Murúa,F. (2001). Inventario de la avifauna del parque natural Ischigualasto, San Juan, Argentina. Nótulas Faunísticas. 3: 1-4. Adams,M.P., Cooper,J.H., and Collar,N.J. (2003). Extinct and endangered ('E&E') birds: a proposed list for collection catalogues. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 123A: 338-354. Agnolin,F.L. (2009). Sobre en complejo Aratinga mitrata (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae) en el noroeste Argentino. Comentarios sistemáticos. Nótulas Faunísticas - Segunda Serie. 31: 1-5. Ahlström,P. and Mild,K. (2003.) Pipits & wagtails of Europe, Asia and North America. Identification and systematics. Christopher Helm. London, UK. Pp. 1-496. Akinpelu,A.I. (1994). Breeding seasons of three estrildid species in Ife-Ife, Nigeria. Malimbus. 16:(2): 94-99. Akinpelu,A.I. (1994). Moult and weight cycles in two species of Lonchura in Ife-Ife, Nigeria. Malimbus . 16:(2): 88-93. Aleixo,A. (1997). Composition of mixed-species bird flocks and abundance of flocking species in a semideciduous forest of southeastern Brazil. Ararajuba. 5:(1): 11-18. -

(Alopochen Aegyptiaca) in the Contiguous United States Author(S): Corey T

History, Current Distribution, and Status of the Egyptian Goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca) In the Contiguous United States Author(s): Corey T. Callaghan and Daniel M. Brooks Source: The Southwestern Naturalist, 62(4):296-300. Published By: Southwestern Association of Naturalists https://doi.org/10.1894/0038-4909-62.4.296 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1894/0038-4909-62.4.296 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. 296 The Southwestern Naturalist vol. 62, no. 4 THE SOUTHWESTERN NATURALIST 62(4): 296–300 HISTORY, CURRENT DISTRIBUTION, AND STATUS OF THE EGYPTIAN GOOSE (ALOPOCHEN AEGYPTIACA) IN THE CONTIGUOUS UNITED STATES COREY T. C ALLAGHAN* AND DANIEL M. BROOKS Centre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, 2052, Australia (CTC) Houston Museum of Natural Science, Department of Vertebrate Zoology, 5555 Hermann Park Drive, Houston, TX 77030-1799 (DMB) *Correspondent: [email protected] ABSTRACT—We summarize the history, current distribution, and status of Egyptian geese (Alopochen aegyptiaca) in the contiguous United States, using published records and the eBird database of bird observations. -

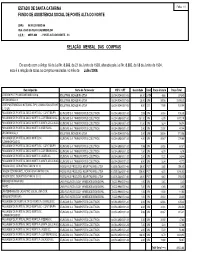

Betha Compras

ESTADO DE SANTA CATARINA Folha: 1/1 FUNDO DE ASSISTENCIA SOCIAL DE PONTE ALTA DO NORTE CNPJ: 95.991.287/0002-56 RUA JOAO DA SILVA CALOMENO,243 C.E.P.: 89535-000 - PONTE ALTA DO NORTE - SC RELAÇÃO MENSAL DAS COMPRAS De acordo com o Artigo 16 da Lei Nr. 8.666, de 21 de Junho de 1993, alterada pela Lei Nr. 8.883, de 08 de Junho de 1994, esta é a relação de todas as compras realizadas no mês de Julho/2009. Bem Adquirido Nome do Fornecedor CNPJ / CPFQuantidadeUnid Preço Unitário Preço Total LEITE EM PO TIPO INSTANTANEO 400 g. INDUSTRIAL MOAGEIRA LTDA 83.054.924/0001-06 80,00 LATA 4,68 374,40 CESTA BASICA_2 INDUSTRIAL MOAGEIRA LTDA 83.054.924/0001-06 35,00 UNI 59,98 2.099,30 LEITE PASTEURIZADO INTEGRAL TIPO LONGA VIDA UAT/UHT INDUSTRIAL MOAGEIRA LTDA 83.054.924/0001-06 6,00 CX 17,99 107,94 C/ 12 UN PASSAGEM DE PONTE ALTA DO NORTE/SC - CURITIBA/PR REUNIDAS S.A. TRANSPORTES COLETIVOS 83.054.395/0001-32 2,958 UN 33,93 100,35 PASSAGEM DE PONTE ALTA DO NORTE A CURITIBANOS/SC. REUNIDAS S.A. TRANSPORTES COLETIVOS 83.054.395/0001-32 261,00 UN 6,79 1.772,19 PASSAGEM DE PONTE ALTA DO NORTE A SANTA CECILIA/SC. REUNIDAS S.A. TRANSPORTES COLETIVOS 83.054.395/0001-32 11,00 UN 5,34 58,74 PASSAGEM DE PONTE ALTA DO NORTE A VIDEIRA/SC. REUNIDAS S.A. TRANSPORTES COLETIVOS 83.054.395/0001-32 2,00 UN 23,92 47,84 CESTA BASICA_2 INDUSTRIAL MOAGEIRA LTDA 83.054.924/0001-06 2,00 UNI 59,98 119,96 PASSAGEM DE PONTE ALTA DO NORTE/SC - REUNIDAS S.A.