Summary of 2011 Massachusetts American Oystercatcher Census

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massachusetts Commercial Fishing Port Profiles

MASSACHUSETTS COMMERCIAL FISHING PORT PROFILES The Massachusetts Commercial Fishing Port Profiles were developed through a collaboration between the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, the University of Massachusetts Boston’s Urban Harbors Institute, and the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance. Using data from commercial regional permits, the Atlantic Coastal Cooperative Statistics Program’s (ACCSP) Standard Atlantic Fisheries Information System (SAFIS) Dealer Database, and harbormaster and fishermen surveys, these profiles provide an overview of the commercial fishing activity and infrastructure within each municipality. The Port Profiles are part of a larger report which describes the status of the Commonwealth’s commercial fishing and port infrastructure, as well as how profile data can inform policy, programming, funding, infrastructure improvements, and other important industry- related decisions. For the full report, visit the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries website. Key Terms: Permitted Harvesters: Commercially permitted harvesters residing in the municipality Vessels: Commercially permitted vessels with the municipality listed as the homeport Trips: Discrete commercial trips unloading fish or shellfish in this municipality Active Permitted Harvesters: Commercially permitted harvesters with at least one reported trans- action in a given year Active Dealers: Permitted dealers with at least one reported purchase from a harvester in a given year Ex-Vessel Value: Total amount ($) paid directly to permitted harvesters by dealers at the first point of sale file Port Port SCITUATE Pro Located on the South Shore, Scituate has three harbors: Scituate, North River, and South River- Humarock. Permitted commercial fisheries, which may or may not be active during the survey period, include: Lobster Pot, Dragger, Gillnetter, Clam Dredge, Scallop Dredge, Rod & Reel, For Hire/ Charter. -

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha's Vineyard

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha’s Vineyard Timothy M. Boland, Executive Director, The Polly Hill Arboretum, West Tisbury, MA 02575 USA Martha’s Vineyard is many things: a place of magical beauty, a historical landscape, an environmental habitat, a summer vacation spot, a year-round home. The island has witnessed wide-scale deforestation several times since its settlement by Europeans in 1602; yet, remarkably, existing habitats rich in biodiversity speak to the resiliency of nature. In fact, despite repeated disturbances, both anthropogenic and natural (hurricanes and fire), the island supports the rarest ecosystem (sand plain) found in Massachusetts (Barbour, H., Simmons, T, Swain, P, and Woolsey, H. 1998). In particular, the scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia Wangenh.) dominates frost bottoms and outwash plains sustaining globally rare lepidopteron species, and formerly supported the existence of an extinct ground-dwelling bird, a lesson for future generations on the importance of habitat preservation. European Settlement and Early Land Transformation In 1602 the British merchant sailor Bartholomew Gosnold arrived in North America having made the six-week boat journey from Falmouth, England. Landing on the nearby mainland the crew found abundant codfish and Gosnold named the land Cape Cod. Further exploration of the chain of nearby islands immediately southwest of Cape Cod included a brief stopover on Cuttyhunk Island, also named by Gosnold. The principle mission was to map and explore the region and it included a dedicated effort to procure the roots of sassafras (Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees) which were believed at the time to be medicinally valuable (Banks, 1917). -

1 Michael Graikoski and Porter Hoagland1 I. Introduction Along The

COMPARING POLICIES FOR ENCOURAGING RETREAT FROM THE MASSACHUSETTS COAST Michael Graikoski and Porter Hoagland1 I. Introduction Along the US Atlantic coast, the lands and infrastructure located on barrier islands and beaches and in backbay estuarine environments face mounting threats from king tides, storm surges, and sea-level rise.2 From the late 19th century to the present, sea-level rise on the United States’ Atlantic coast has been more rapid than any other century-scale increase over the last 2000 years.3 Even slight increases in sea-level rise now have been hypothesized to significantly increase the risks of coastal flooding in many places.4 In New England, some of the most severe northeast storms (“nor’easters”) have become notorious for consequent extreme losses of coastal properties. Some 1 Michael Graikoski, Guest Student, Marine Policy Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution & Porter Hoagland, Senior Research Specialist, Marine Policy Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. This article was prepared under award number NA10OAR4170083 (WHOI Sea Grant Omnibus) from the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Northeast Regional Sea Grant Consortium project 2014-R/P-NERR- 14-1-REG); award number AGS-1518503 from the US National Science Foundation (Dynamics of Coupled Natural and Human Systems [CNH]); award number OCE-1333826 from the US National Science Foundation (Science and Engineering for Sustainability [SEES]) to the Virginia Institute of Marine Science; and with support from the J. Seward Johnson Fund in Support of the Marine Policy Center. The authors thank Chris Hein, John Duff, Di Jin, Peter Rosen, Andy Fallon, Billy Phalen, and Sarah Ertle for helpful insights and suggestions and Jun Qiu for help with the map of Plum Island in Figure 1. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 62, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society Fall 2001 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 62, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright © 2001 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. BULLETIN OF THE MASSACHUSElTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 62(2) FALL 2001 CONTENTS: In Memoriam: Great Moose (Russell Herbert Gardner) . Mark Choquet 34 A Tribute to Russell H. Gardner (Great Moose) . Kathryn Fairbanks 39 Reminiscences of Russell H. Gardner (Great Moose) Bernard A. Otto 41 The Many-Storied Danson Stone of Middleborough, Massachusetts Russell H. Gardner (Great Moose) 44 Discovery and Rediscovery of a Remnant 17th Century Narragansett Burial Ground' in Warwick, Rhode Island Alan Leveillee 46 On the Shore of a Pleistocene Lake: the Wamsutta Site (I9-NF-70) Jim Chandler 52 The Blue Heron Site, Marshfield, Massachusetts (l9-PL-847) . John MacIntyre 63 A Fertility Symbol from Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts . Ethel Twichell 68 Contributors 33 Editor's Note 33 THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, Inc. P.O.Box 700, Middleborough, Massachusetts 02346 MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Officers: Ronald Dalton, 100 Brookhaven Dr., Attleboro, MA 02703 President Donald Gammons, 7 Virginia Dr., Lakeville, MA 02347 Vice President Wilford H. Couts Jr., 127 Washburn Street, Northborough, MA 01532 Clerk Edwin C. Ballard, 26 Heritage Rd., Rehoboth, MA 02769 .. Treasurer Eugene Winter, 54 Trull Ln., Lowell, MA 01852 Museum Coordinator Shirley Blancke, 579 Annursnac Hill Rd., Concord, MA 01742 Bulletin Editor Curtiss Hoffman, 58 Hilldale Rd., Ashland, MA 01721 .................. -

2020 Coastal Massachusetts COASTSWEEP Results (People

COASTSWEEP 2020 - Cleanup Results Town Location Group Name People Pounds Miles TOTALS 703 9016.2 151.64 Arlington Mystic River near River Street 1 2 Arlington Mystic River 1 2.12 1.20 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 4 27.5 3.95 Barnstable Jublilation Way, Osterville 1 0.03 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 2 10.13 0.53 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 1 8 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 2 8.25 1.07 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 3 14.25 1.16 Barnstable Oregon Beach, Cotuit 6 30 Barnstable KalMus Park Beach 2 23.63 0.05 Barnstable Dowes Beach, East Bay Cape Cod Anti-Litter Coalition 4 25.03 0.29 Barnstable Osterville Point, Osterville Cape Cod Anti-Litter Coalition 1 3.78 0.09 Barnstable Louisburg Square, Centerville 2 Barnstable Hathaway's Ponds 2 4.1 0.52 Barnstable Hathaway's Ponds 2 5.37 0.52 Barnstable Eagle Pond, Cotuit Lily & Grace Walker 2 23.75 3.26 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 2 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.07 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.03 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.11 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.18 0.01 Beverly Dane Street Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.36 0.04 Beverly Clifford Ave 2 11.46 0.03 Beverly Near David Lynch Park 1 0.43 0.03 Beverly Rice's Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 3 28.61 0.03 Beverly Rice's Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 3 1.61 Beverly Rice's Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.07 COASTSWEEP 2020 - Cleanup Results Town -

Summary of 2017 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census Data

SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS Bill Byrne, MassWildlife SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS ABSTRACT This report summarizes data on abundance, distribution, and reproductive success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) in Massachusetts during the 2017 breeding season. Observers reported breeding pairs of Piping Plovers present at 147 sites; 180 additional sites were surveyed at least once, but no breeding pairs were detected at them. The population increased 1.4% relative to 2016. The Index Count (statewide census conducted 1-9 June) was 633 pairs, and the Adjusted Total Count (estimated total number of breeding pairs statewide for the entire 2017 breeding season) was 650.5 pairs. A total of 688 chicks were reported fledged in 2017, for an overall productivity of 1.07 fledglings per pair, based on data from 98.4% of pairs. Prepared by: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 2 SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS INTRODUCTION Piping Plovers are small, sand-colored shorebirds that nest on sandy beaches and dunes along the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Newfoundland. The U.S. Atlantic Coast population of Piping Plovers has been federally listed as Threatened, pursuant to the U.S. Endangered Species Act, since 1986. The species is also listed as Threatened by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife pursuant to Massachusetts’ Endangered Species Act. Population monitoring is an integral part of recovery efforts for Atlantic Coast Piping Plovers (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996, Hecht and Melvin 2009a, b). It allows wildlife managers to identify limiting factors, assess effects of management actions and regulatory protection, and track progress toward recovery. -

Ipswich Where to Go • What to See • What to Do

FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:55 PM DESTINATION IPSWICH WHERE TO GO • WHAT TO SEE • WHAT TO DO Nicole Goodhue Boyd Nicole The Salem News PHOTO/ FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:57 PM S2 • Friday, June 23, 2017 June • Friday, DESTINATION IPSWICH DESTINATION Trust in Our Family Business The Salem News • News Salem The Marcorelle’s Fine Wine, Liquor & Beer Specializing in beverage catering, functions and delivery since 1935. 30 Central Street, Ipswich, MA 01938, Phone: 978-356-5400 Proud retailer of Ipswich Ale Brewery products Visit ipswichalebrewery.com for brewery tour & restaurant hours. FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:58 PM S3 The Salem News • News Salem The Family Owned & Operated Since 1922 IPSWICH DESTINATION • Send someone flowers, make someone happy • Colorful Hanging Baskets and 23, 2017 June • Friday, colorful flowering plants for all summer beauty • Annuals and Perennials galore • Fun selection of quality succulents & air plants • Walk in cut flower cooler • Creative Floral Arrangements • One of a Kind Gifts & Cards Friend us on www.gordonblooms.com 24 Essex Rd. l Ipswich, MA l 978.356.2955 FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:58 PM S4 RECREATION • Friday, June 23, 2017 June • Friday, DESTINATION IPSWICH DESTINATION The Salem News • News Salem The File photos The rooftop views from the Great House at the Crane Estate Crane Beach is one of the most popular go-to spots for playing on the sand and in the water. include the “allee” that leads to the Atlantic Ocean. Explore the sprawling waterways and trails Visitors looking to get through the end of October. -

Modeling Population Dynamics of Roseate Terns (Sterna Dougallii) In

Ecological Modelling 368 (2018) 298–311 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Modelling j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolmodel Modeling population dynamics of roseate terns (Sterna dougallii) in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean a,b,c,∗ d e b Manuel García-Quismondo , Ian C.T. Nisbet , Carolyn Mostello , J. Michael Reed a Research Group on Natural Computing, University of Sevilla, ETS Ingeniería Informática, Av. Reina Mercedes, s/n, Sevilla 41012, Spain b Dept. of Biology, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155, USA c Darrin Fresh Water Institute, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 110 8th Street, 307 MRC, Troy, NY 12180, USA d I.C.T. Nisbet & Company, 150 Alder Lane, North Falmouth, MA 02556, USA e Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The endangered population of roseate terns (Sterna dougallii) in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean consists Received 12 September 2017 of a network of large and small breeding colonies on islands. This type of fragmented population poses an Received in revised form 5 December 2017 exceptional opportunity to investigate dispersal, a mechanism that is fundamental in population dynam- Accepted 6 December 2017 ics and is crucial to understand the spatio-temporal and genetic structure of animal populations. Dispersal is difficult to study because it requires concurrent data compilation at multiple sites. Models of popula- Keywords: tion dynamics in birds that focus on dispersal and include a large number of breeding sites are rare in Roseate terns literature. -

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Energy Facilities Siting Board

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS ENERGY FACILITIES SITING BOARD ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 164, § 69J for Approval to Construct, Operate, and ) Maintain Transmission Facilities in Massachusetts ) for the Delivery of Energy from an Offshore Wind ) EFSB 20-01 Energy Facility Located in Federal Waters to an ) NSTAR Electric (d/b/a Eversource Energy) ) Substation Located in the Town of Barnstable, ) Massachusetts. ) ) ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 40A, § 3 for Exemptions from the Operation of the ) Zoning Ordinance of the Town of Barnstable for ) the Construction and Operation of New Transmission Facilities for the Delivery of Energy ) D.P.U. 20-56 from an Offshore Wind Energy Facility Located in ) Federal Waters to an NSTAR Electric (d/b/a. ) Eversource Energy) Substation Located in the ) Town of Barnstable, Massachusetts. ) ) ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 164, § 72 for Approval to Construct, Operate, and ) Maintain Transmission Lines in Massachusetts for ) the Delivery of Energy from an Offshore Wind ) D.P.U 20-57 Energy Facility Located in Federal Waters to an ) NSTAR Electric (d/b/a Eversource Energy) ) Substation Located in the Town of Barnstable, ) Massachusetts. ) ) AFFIDAVIT OF AARON LANG I, Aaron Lang, Esq., do depose and state as follows: 1. I make this affidavit of my own personal knowledge. 2. I am an attorney at Foley Hoag LLP, counsel for Vineyard Wind LLC (“Vineyard Wind”) in this proceeding before the Energy Facilities Siting Board. 3. On September 16, 2020, the Presiding Officer issued a letter to Vineyard Wind containing translation, publication, posting, and service requirements for the Notice of Adjudication and Public Comment Hearing (“Notice”) and the Notice of Public Comment Hearing Please Read Document (“Please Read Document”) in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

Atlantic Cod5 0 5 D

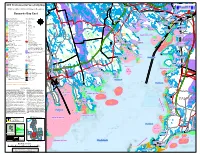

OND P Y D N S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S A S S S S S L S P TARKILN HILL O LINCOLN HILL E C G T G ELLIS POND A i S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S C S S S S Sb S S S S G L b ROBBINS BOG s E B I S r t P o N W o O o n N k NYE BOG Diamondback G y D Þ S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S COWEN CORNER R ! R u e W W S n , d B W "! A W H Þ terrapin W r s D h S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S O S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S ! S S S S S S S S S S l A N WAREHAM CENTER o e O R , o 5 y k B M P S , "! "! r G E "! Year-round o D DEP Environmental Sensitivity Map P S N ok CAMP N PO S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S es H S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SAR S S S S S S S S S S S S S S O t W SNIPATUIT W ED L B O C 5 ra E n P "! LITTLE c ROGERS BOG h O S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S Si N S S S S S S S S S S S S S A S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S BSUTTESRMILKS S p D American lobster G pi A UNION ca W BAY W n DaggerblAaMde grass shrimp POND RI R R VE Þ 4 S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S i S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S )S S S S S S v + ! "! m er "! SAND la W W ÞÞ WAREHAM DICKS POND Þ POND Alewife c Þ S ! ¡[ ! G ! d S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S h W S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S 4 S Sr S S S S S S S S ! i BUTTERMILK e _ S b Þ "! a NOAA Sensitive Habitat and Biological Resources q r b "! m ! h u s M ( BANGS BOG a a B BAY n m a Alewife g OAKDALE r t EAST WAREHAM B S S S S S S S S S S S S S -

Summary of 2020 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census Data

SUMMARY OF THE 2020 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS Bill Byrne, MassWildlife Prepared by: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife March 2021 SUMMARY OF THE 2020 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS ABSTRACT This report summarizes data on abundance, distribution, and reproductive success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) in Massachusetts during the 2020 breeding season. Observers reported breeding pairs of Piping Plovers present at 180 sites; 156 additional sites were surveyed at least once, but no breeding pairs were detected at them. The population increased 6.9% relative to 2019. The Index Count (statewide census conducted 1-9 June) was 779 pairs, and the Adjusted Total Count (estimated total number of breeding pairs statewide for the entire 2020 breeding season) was 794.5 pairs. A total of 1,034 chicks were reported fledged in 2020, for an overall productivity of 1.31 fledglings per pair, based on data from 99.4% of pairs. 2 SUMMARY OF THE 2020 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS INTRODUCTION Piping Plovers are small, sand-colored shorebirds that nest on sandy beaches and dunes along the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Newfoundland. The U.S. Atlantic Coast population of Piping Plovers has been federally listed as Threatened, pursuant to the U.S. Endangered Species Act, since 1986. The species is also listed as Threatened by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife pursuant to the Massachusetts’ Endangered Species Act. Population monitoring is an integral part of recovery efforts for Atlantic Coast Piping Plovers (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996, Hecht and Melvin 2009a, b).