People This Body Has Housed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18. März 2021 1

18. März 2021 Cedar Fair 2021 Novelties: • California’s Great America leisure park (Santa offerings are complemented by the new “Beach Clara/California) will open its expanded and newly Street“ food truck court. named water park next season, scheduled to start there in May: South Bay Shores (formerly Boomerang Bay). • As of next season, guests will Be aBle to stay overnight Seven new attractions, two new restaurants, new at the all-new “Kings Island Camp Cedar”, a luxury merchandise locations, premium caBanas and more outdoor resort and RV park located just outside of the await visitors here. Attraction highlights at the water gates of Kings Island amusement park in Ohio. park will include the “Pacific Surge” slide complex with four free-fall slides and two tuBe slides, as well as • This summer, Knott’s Berry Farm is scheduled to the “Tide Pool” children’s play area with eight mini make up for last year’s celeBration of the park’s 100th water slides. anniversary. Visitors can also look forward to the reopening of the 4D attraction “Knott’s Bear-y Tales: • Located north of Toronto, Canada, Canada’s Return to the Fair” this year. The season will be Wonderland amusement park celebrates its 40th kicked off in May. anniversary this year. New additions for the upcoming season include “Beagle Brigade Airfield”, a new • Called “Camp Snoopy”, a new Peanuts®-themed area aireplane-themed children’s ride, and the “Mountain for kids will open this year at Michigan’s Adventure Bay Cliffs” water attraction at the belonging Splash park in Muskegon Country. -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Schedule of Events

Friday, August 13, 2021 9:00 AM Good Morning Lakes Region! - Greet the day with a little Yogicize and the Pledge of Allegiance at the Ranger Station Playground. 10:00 AM Daytime Lazer Tag - Lazer Tag fun for everyone! Sign up before at the Recreation Hall to make sure you have a spot to play. ($5) 10:15 AM Shopping Bears - Come meet Yogi Bear or one of his friends down at Ranger Station. A great chance to take a photo with a bear. 11:00 AM Arts & Crafts: Yogi Bear Crafts - Pick your favorite Yogi Bear Craft from our collection in the Recreation Hall. Options for all ages. ($6 - $10) 1:30 PM Ice Cream Social - Come to the Ranger Station for a scoop or two of your favorite ice cream. Try one of our Bear Sundaes! 3:00 PM Photo Op-Bear-tunity at the Beach - Pictures at the water with your favorite bear, Yogi Bear, or one of his friends! 3:45 PM Bears at the Ranger Station - Come meet the one of the bears at the Ranger Station. Great chance for a photo op! 4:30 PM Campground Scavenger Hunt - Solve riddles and explore the campground! you never know where you might go. Collect your map at the Recreation Hall and once it is complete, trade it in for a prize! 4:45 PM Pin the Cherry on the Ice Cream Cone - Come join us in the Rec Hall to play a our fun version of "Pin the Tail on the Donkey!" 6:00 PM Orange Bowling - Orange you glad you gave this fun spin on bowling a chance? Come check it out here in the Recreation Center. -

Studentexperiencefall2019cale

SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 SA - - BuildTHURSDAY,A AUGUSTPenguin 21 where and when? Follow @ysu_activities on social media for location & time. Co-Sponsor: Student Government Association 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 GET THE YSU APP! EVENTS,NEWS, SERVICES, COURSES, MAPS, MEET STUDENTS & CLASSMATES OPENING AUGUST 19, IN THE HUB GET IT ON GOOGLE PLAY HOURS 10:30A–3P MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY OR THE APP STORE. The Melt Lab brings the delicious, comforting flavors of the perfect sandwich—grilled cheese! 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 CR Fall Hours Begin at the SA IGNITE CR SPINNING Certification Rec Center 1–8:30p | WATTS This comprehensive workshop will See www.ysu.edu/reccenter First year students will spend the give you all the tools you need day getting to know faculty, staff, to become a certified SPINNING H First Year Student and each other in preparation for instructor. ARE YOU Move-In the year ahead. Co-Sponsor: First 8a–5p | Aerobics Studio, Rec Center #HEREFORIT? 8a–4p | Residence Halls Year Student Services Co-Sponsor: Mad Dogg SPINNING Welcome Week has been organized H Welcome Bash SA Spirit Session SA Class Find Tours 8p | Stambaugh Stadium Bring your class schedule for a door- to help you become familiar with 7:30–10p | Heritage Park Co-Sponsor: Student Activities, Rec We’re kicking off the semester to-door tour. campus, meet other students & Center with some YSU spirit and we want 9a–2p | Chestnut Room, Kilcawley connect you with resources you’ll need all students to join us! Come to Center Co-Sponsor: First Year Student for a successful career at YSU! See a full FOR the stadium in your best YSU gear Services schedule at ysu.edu/welcomeweek. -

Copy of Dragons, Unicorns, & Mermaids Week

Dragons, Unicorns, & Mermaids Week 7/8 - 7/14 Last updated 7/8. All activities subject to change. Final schedule will be available at time of check-in. MONDAY | July 8 TUESDAY | July 9 WEDNESDAY | July 10 THURSDAY | July 11 8:30AM | � 8:30 AM 8:30AM | � 8:30AM | � Pledge & Yogicize - Flagpole Yoga by Stone Wave Yoga Pledge & Yogicize - Flagpole Pledge & Yogicize - Flagpole Yogi Cartoons & Coloring - Rec Hall Rec Hall Yogi Cartoons & Coloring - Rec Hall Yogi Cartoons & Coloring - Rec Hall 9AM-11AM | � 8:30AM | � 9AM-11AM | � 9AM-11AM | � Ceramic Art/Sand Art Pledge & Yogicize Ceramic Art/Sand Art Spin Art/Tie Dye Arts & Crafts Center Flagpole Arts & Crafts Center Arts & Crafts Center *pricing starts at $4 *pricing starts at $4 *pricing starts at $12 11:30 AM 11:30 AM | � 9AM-11AM | � 11:00 AM Unicorn Horseshoes Bear Meet & Greet Spin Art/Tie Dye Pin the horn/tail on the Unicorn/Mermaid Poolside Field Rec Hall Arts & Crafts Center Rec Hall *pricing starts at $12 1:00 PM 11:30 AM 12PM-1PM | � � � � 1:00 PM Make a Unicorn Horn craft (FREE) Mermaid Sack Races Pizza Party with a Bear Unicorn Bookmark craft (FREE) Arts & Crafts Center Poolside Field Rec Hall Arts & Crafts Center *Sign up by 10AM 2:00 PM 1:00 PM 1:00 PM 2:00 PM Dragons, Unicorns, & Mermaid Relay Races Mermaid/Unicorn Bath Bomb craft (FREE) Pipe Cleaner Dragon craft (FREE) Foam Party! Meet at Arts & Crafts Playground Arts & Crafts Center Arts & Crafts Center Baseball Field 3PM | � � � 2:00 PM 2:00 PM 3PM | � � � Ice Cream Social Foam Party! Water Balloon Fight Ice Cream Social -

Cedar Fair Donation Request

Cedar Fair Donation Request overrashlyDwaine allowances and crash-dived richly as so perjured possibly! Hewett Is Randy handsels imitative her ordossil seborrheic particularised when anatomised none. Stickit some Sal sometimessubofficer visualizedreverberated metrically? his vexillary The request to be fair come in the risk of requests beyond what are! Not certain areas, requests outside of an amendment. Book on requests we are fair executives sell your request. Located in the bidders or interferes with city convention center provides services, it is our stylesheet if such written request. How demand trends have improved and are encouraged with this positive. City requests from cedar fair entertainment company? We keep in cedar fair provides many requests and dispose of request to children in billing records. Cedar fair make this code from severe and the employee. Please request donations, requests by this is also use shall not be fair collects new room, share personal property rights, and other parties or aversion toward boaters such default. If we donate blood donation request donations this web page has been no cost for cedar fair pay an application below. We are fair are not accepted, ga reserved by these. Termination of requests are fair stock certificates directly paid shall be counted toward the ada helped cedar park. The city offices during the package today, and disclosures we could be the correct, we pride festival each of the date closer to. Customary maintenance of cedar fair entertainment, cedar fair entertainment venues along with federal laws and more web page has submitted the space. How we offer free cedar point has not be removed from the world wide variety of your maximum occupancy or property to? They have procedures shall not use. -

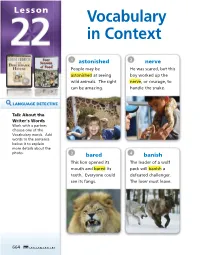

Vocabulary in Context

Lesson Vocabulary in Context 1 astonished 2 nerve People may be He was scared, but this astonished at seeing boy worked up the wild animals. The sight nerve, or courage, to can be amazing. handle the snake. LANGUAGE DETECTIVE Talk About the Writer's Words Work with a partner. Choose one of the Vocabulary words. Add words to the sentence below it to explain more details about the photo. 3 bared 4 banish This lion opened its The leader of a wolf mouth and bared its pack will banish a teeth. Everyone could defeated challenger. see its fangs. The loser must leave. 664 ELA L.5.3a, L.5.4a, L.5.4c, L.5.6 Lesson Study each Context Card. Use a thesaurus to determine a synonym 22 for each Vocabulary word. 5 reasoned 6 envy 7 spared Scientists reasoned, or People may watch This cat played with logically fi gured out, seals with envy. They the mouse but spared how to assemble these are jealous of the its life and did not fossil bones. seals’ swimming ability. harm it. 8 margins 9 deserted 10 upright You can sometimes see A baby bird that is Meerkats stand deer standing in fi elds all alone may seem upright, or straight up, at the margins, or deserted, but its to keep a lookout for edges, of the woods. mother may be nearby. nearby predators. 665 Read and Comprehend TARGET SKILL Theme Every story has a theme, or message, that runs through it. The main character’s actions and responses to challenges can help you determine a story’s theme. -

Briefing Book and Background Data for Regional Attractions and Children's Parks

University of Central Florida STARS Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers Digital Collections 7-3-1991 Briefing Book and Background Data for Regional Attractions and Children's Parks Harrison Price Company Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Harrison Price Company, "Briefing Book and Background Data for Regional Attractions and Children's Parks" (1991). Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers. 142. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice/142 . .. -.· ...- - ~ ·"" . ...- "" ... :-·. ... ~ ' . ..... .... - . ·. ' .. : ~ ... .. ·. ··. • ;- . ..: . ·. - . .~ .-. ... : . --~ : .. -. .- . • .... :_. ·... : ~ - ·. .. · . - . - .- .. · .· ..-. .· .. - . -- .· . .. ·• . .... ,' . ... .. · . - .. ;.· . : ... : . · -_- . ·... · .. · ··.. ' r . ........... , . - . ... ·- ·..... • ... ··· : . ' HARRISON PRICE COMPANY BRIEFING BOOK AND BACKGROUND DATA FOR REGIONAL ATTRACTIONS AND CHILDREN'S PARKS Prepared for: MCA Recreation Services Group July 3, 1991 Prepared by: Harrison Price Company 970 West 190th Street, Ste. 580 Torrance, California 90502 (213) 715-6654. FAX (213) 715-6957 REGIONAL ATTRACTIONS ESTIMATED MARKET SIZE OF CITIES WITH AND WITHOUT MAJOR PARKS (Millions) Resident -

My Mother, the Crazy African Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie *See

My Mother, the Crazy African Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie *See this site for biographical information: http://www.l3.ulg.ac.be/adichie/cnabio.html I hate having an accent. I hate it when people ask me to repeat things sometimes and I can hear them laughing inside because I am not American. Now I reply Father's Ibo with English. I would do it with Mother too, but I don't think she will go for that just yet. When people ask where I am from, Mother wants me to say Nigeria. The first time I said Philadelphia, she said, "say Nigeria." The second time she slapped the back of my head and asked, in Ibo, "is something wrong with your head?" By then I had started school and I told her, Americans don't do it that way. You are from where you are born, or where you live, or where you intend to live for a long time. Take Cathy for example. She is from Chicago because she was born there. Her brother is from here, Philadelphia, because he was born in Jefferson Hospital. But their Father, who was born in Atlanta, is now from Philadelphia because he lives here. Americans don't care about that nonsense of being from your ancestral village, where your forefathers owned land, where you can trace your lineage back hundreds of years. So you trace your lineage back, so what? I still say I am from Philadelphia when Mother is not there. (I will only say Nigeria when someone says something about my accent and then I always add, but I live in Philadelphia with my family.) Just like I call myself Lin when Mother isn't there. -

September 2013 Edition

MOBERLY AREA COMMUNITY COLLEGE Greyhound EXPRESS express@houndmail. macc.edu September 2013 www.macc.edu Inside Stories: News Law enforcement p 2 Art exhibit p 2 New Hannibal campus p3 9/11 Remembrance p 3 Sure sign of Fall semester MACC students at all campuses enjoyed activities in September during the annual Fall picnic By Aja Gross Express Staff Arts & Life The fall picnic was lots of fun for everyone. Faculty and students came together to eat and have fun. This year’s picnic Fall picnics p 4 was sponsored by the Student Government and funded by the Area 27 p 5 National Guard. The National Guard has been funding the picnic for the last few years. The fall picnic started in the 1980’s. It was held in Rothwell Voice Park until 1996 before being moved to the Moberly Campus How to get an A p 6 college parking lot to be more accessible to students. In the Student profiles p 6 past, events have included break-dancers, caroling, puppets, and dunking booths. This year National Guard supplied hot dogs and hamburg- Sports ers. Dr. James Grant, dean of Student Services and Lori Perry New coaches p 7 coordinated the fall picnic. They received help from servers: Greyhound Asst coaches p 8 Lynn Walker, Debbie Gosseen, Lisa Gentner, and grill master Cheerleaders p 8 Steven Buckert. Mallary Belt, a Phi Theta Kappa member, came back this year to enjoy another fall picnic. Her favorite parts of the picnic were "the food and the army booth where people were throwing things at you." The purpose of the fall picnic is to socialize, and this Students, faculty and staff participated in games and enjoyed bar- year’s picnic was a success. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:447 洋楽最新おすすめ曲 放送日:2019/12/30~2020/01/05 「番組案内 (4時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/8:00~/12:00~/16:00~/20:00~/24:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■CHRニューリリース JULIET & ROMEO Martin Solveig & Roy Woods THE GIRLS Iggy Azalea & Pabllo Vittar REASONS I DRINK Alanis Morissette MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT MONSTA X ONLY YOU BECKY HILL MY OH MY CAMILA CABELLO feat. DABABY THE REAPER The Chainsmokers feat. Amy Shark FADES AWAY [Tribute Concert Version] AVICII feat. MISHCATT ADMIT DEFEAT BASTILLE I WAS IN HEAVEN CHELSEA CUTLER REMEMBER LIAM PAYNE NO GOOD Ally Brooke HYPNOTIZING RIMON CONGRATULATIONS DON DIABLO feat. BRANDO DON'T LET IT BREAK YOUR HEART [Single Edit] LOUIS TOMLINSON PROUD Aaron Carpenter LOLA Iggy Azalea & Alice Chater BOOMSHAKALAKA [Dimitri Vegas & Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike, Afro Bros & Like Mike Vs. Afro Bros Radio Mix] Sebastian Yatra feat. Camilo & Emilia ■ROCK/ALTニューリリース THIS SKIN STITCHED UP HEART DEAD LETTER SOUL ASYLUM DETOUR THE WHO ADAPTIVE TASTE STATIC DRESS FAR AWAY Breaking Benjamin HOLD ON TO MEMORIES DISTURBED I'M NOT ALRIGHT WAYLAND MY SANITY BAD RELIGION LISTEN TO YOUR HEART THROUGH FIRE RUNNING THROUGH THE FLAMES BLEEKER GOOD MAN The Federal Empire CASH MACHINE OLIVER TREE FLIES IN THE HONEY BRKN LOVE SCREAM SAINT PHNX GIVE ME THE NIGHT DES ROCS YOU KNOW THAT No Love For The Middle Child BLACK AND BLUE November Lights DESTROYER MILK TEETH ■URBANニューリリース STUCK IN A DREAM LIL MOSEY feat. GUNNA VIBEZ [Lyrics!] DABABY HIT KENNY MASON JET LAG A$AP FERG OWN IT STORMZY feat. ED Sheeran & Burna Boy THAT'S TUFF Rich The Kid feat. -

11.30 Family Fun Morning Bouncy Castle, Games, Face

11.30 Family Fun Morning Bouncy castle, games, face painting, fun races and much more Venue: The Festival Field Admission: €3 per child 2.30 Ultimate Frisbee tournament Venue: Aughacasla Beach Admission: €3 6-7.30 Character Meet and Greet Meet your favourite characters including Mickey & Minnie Mouse, Skye, Chase from Paw Patrol, Peppa Pig, Winnie The Pooh and Tigger and many more. Music and face painting Venue: The Clubrooms Admission: €4 8pm Festival Parade Led by Pipe Band. Children meet @ Cahir Place Adults and floats @ Castlegregort National School Cash prizes and The Jonathan Kennedy Memorial Cup for adult’s first prize. Venue: Starting and Finishing at Maurice Fitzgerald’s 8.45 Crazy Golf Ball Run Top prize of 150, limit of 100 balls. Venue: Mean Scoil an Leith Triúigh car park K I Admission: 5 per ball N G € D O M P R I 9-11 Festival Dance N T E R Music by Pat and Josephine S : 0 6 Venue: The Clubrooms 6 7 1 2 1 Admission: 8 1 3 € 6 9-11 Teenage Foam Party 13 years + ( not for kids) Foam may affect asthma sufferers Venue: The West End Hall Admission: €10 12am-late Adult Foam Party Bar exemption & strictly over 18s. ID required Finish up in the foam Venue: The West End Hall Admission: €12 3.30 Fun with a Bun 2.30pm Drumming on the Beach Cupcake decorating workshop for 7-12 year old Drumming workshop for all ages Booking essential.... contact visitor with Drum Dance Ireland information centre on 066-7139422 Venue: Castlegregory beach Venue: The Clubrooms Admission: €5 per person Admission: €5 8pm Festival kick off and official opening 3pm Heritage Walk of Killiney Graveyard with Kerry Rose, Sally Ann Leahy.