Chapter 36C. North Pacific Ocean Contributors: Thomas Therriault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

The Integrated Coastal Zone Management Based on Ecosystem Services

THE INTEGRATED COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT BASED ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES NAKAGAMI Kenichi, Ritsumeikan University, Japan OBATA Norio, Ritsumeikan University, Japan TAKAO Katsuk, Ritsumeikan University, Japan UEHARA Takuro, Ritsumeikan University, Japan SAKURAI Ryo, Ritsumeikan University, Japan OTA Takahiro, Nagasaki University, Japan YOSHIOKA Taisuke, Ritsumeikan University, Japan NIU Jia, Ritsumeikan University, Japan CHEN Xiaochen, Ritsumeikan University, Japan ,MINEO Keito, Kyoto University, Japan [email protected] The Japanese term “Satoumi” inspires us to pursue sound coastal zone governance by taking sustainable development into consideration with “Establishment of Sato-umi in the coastal sea”. The popular ICZM (Integrated Coastal Zone Management) shows us the potential approach toward a coastal area with harmonious interaction between human-being and natural environment. Seto Inland Sea which has undergone serious environmental degradation and anthropogenic changes. In order to recover and sustain its unparalleled values, rebuilding a sound environmental policy system from top to bottom is highly required. The ecosystem services and their monetary values are also estimated buy CVM necessary for sustainability assessment, due to their powerful roles in representing human-coastal zone relationship and supporting sustainability of a “Satoumi” system. The sustainability assessment framework for Seto Inland Sea, which consists of Inclusive Wealth, “Satoumi”, and ecosystem service approach was developed. Key words: Satoumi, ICZM, Seto Inland Sea, Ecosystem service, CVM, Sustainability Ⅰ.INTRODUCTION Japanese term “Satoumi” refers to coastal zone that has sound bio-productivity and biodiversity through human activities, which is composed of five elements. Three factors support the conservation and revitalization of coastal zone, i.e., material circulation, ecosystem and communication. Another two facilitate the realization of “Satoumi”, i.e., field of activity and executors of activity. -

Ocean Currents and the Pacific Garbage Patch

ocean currents and the Pacific Garbage Patch photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography The image above shows a net tow sample from the Pacific Garbage Patch. The sample contains small fish and many small pieces of plastic. The Garbage Patch is primarily composed of this small plastic “confetti” suspended throughout the surface water of the North Pacific Gyre, and is not a island of trash as suggested by some media outlets. The region where the trash converges in the center of the North Pacific Gyre, in a region where surface currents are weak and convergent, thus concentrating large amounts of trash in an area estimated to be close to the size of Texas. With this slide I often show a video clip about the Garbage Patch. Although the links may change, here is one from ABC that I’ve used several times: www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFMW8srq0Qk this video is a bit over the top but it gets the point across. There is additional information from Scripps Institution of Oceanography SEAPLEX experiment: http://sio.ucsd.edu/Expeditions/Seaplex/ and several videos on youtube.com by searching the phrase “SEAPLEX” Pacific garbage patch tiny plastic bits • the worlds largest dump? • filled with tiny plastic “confetti” large plastic debris from the garbage patch photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography little jellyfish photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography These are some of the things you find in the Garbage Patch. The large pieces of plastic, such as bottles, breakdown into tiny particles. Sometimes animals get caught in large pieces of floating trash: photo: NOAA photo: NOAA photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography How do plants and animals interact with small small pieces of plastic? fish larvae growing on plastic Trash in the ocean can cause various problems for the organisms that live there. -

Grade 3 Unit 2 Overview Open Ocean Habitats Introduction

G3 U2 OVR GRADE 3 UNIT 2 OVERVIEW Open Ocean Habitats Introduction The open ocean has always played a vital role in the culture, subsistence, and economic well-being of Hawai‘i’s inhabitants. The Hawaiian Islands lie in the Pacifi c Ocean, a body of water covering more than one-third of the Earth’s surface. In the following four lessons, students learn about open ocean habitats, from the ocean’s lighter surface to the darker bottom fl oor thousands of feet below the surface. Although organisms are scarce in the deep sea, there is a large diversity of organisms in addition to bottom fi sh such as polycheate worms, crustaceans, and bivalve mollusks. They come to realize that few things in the open ocean have adapted to cope with the increased pressure from the weight of the water column at that depth, in complete darkness and frigid temperatures. Students fi nd out, through instruction, presentations, and website research, that the vast open ocean is divided into zones. The pelagic zone consists of the open ocean habitat that begins at the edge of the continental shelf and extends from the surface to the ocean bottom. This zone is further sub-divided into the photic (sunlight) and disphotic (twilight) zones where most ocean organisms live. Below these two sub-zones is the aphotic (darkness) zone. In this unit, students learn about each of the ocean zones, and identify and note animals living in each zone. They also research and keep records of the evolutionary physical features and functions that animals they study have acquired to survive in harsh open ocean habitats. -

Cenozoic Changes in Pacific Absolute Plate Motion A

CENOZOIC CHANGES IN PACIFIC ABSOLUTE PLATE MOTION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS DECEMBER 2003 By Nile Akel Kevis Sterling Thesis Committee: Paul Wessel, Chairperson Loren Kroenke Fred Duennebier We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science in Geology and Geophysics. THESIS COMMITTEE Chairperson ii Abstract Using the polygonal finite rotation method (PFRM) in conjunction with the hotspot- ting technique, a model of Pacific absolute plate motion (APM) from 65 Ma to the present has been created. This model is based primarily on the Hawaiian-Emperor and Louisville hotspot trails but also incorporates the Cobb, Bowie, Kodiak, Foundation, Caroline, Mar- quesas and Pitcairn hotspot trails. Using this model, distinct changes in Pacific APM have been identified at 48, 27, 23, 18, 12 and 6 Ma. These changes are reflected as kinks in the linear trends of Pacific hotspot trails. The sense of motion and timing of a number of circum-Pacific tectonic events appear to be correlated with these changes in Pacific APM. With the model and discussion presented here it is suggested that Pacific hotpots are fixed with respect to one another and with respect to the mantle. If they are moving as some paleomagnetic results suggest, they must be moving coherently in response to large-scale mantle flow. iii List of Tables 4.1 Initial hotspot locations . -

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future As more and more states are incorporating projections of sea-level rise into coastal planning efforts, the states of California, Oregon, and Washington asked the National Research Council to project sea-level rise along their coasts for the years 2030, 2050, and 2100, taking into account the many factors that affect sea-level rise on a local scale. The projections show a sharp distinction at Cape Mendocino in northern California. South of that point, sea-level rise is expected to be very close to global projections; north of that point, sea-level rise is projected to be less than global projections because seismic strain is pushing the land upward. ny significant sea-level In compliance with a rise will pose enor- 2008 executive order, mous risks to the California state agencies have A been incorporating projec- valuable infrastructure, devel- opment, and wetlands that line tions of sea-level rise into much of the 1,600 mile shore- their coastal planning. This line of California, Oregon, and study provides the first Washington. For example, in comprehensive regional San Francisco Bay, two inter- projections of the changes in national airports, the ports of sea level expected in San Francisco and Oakland, a California, Oregon, and naval air station, freeways, Washington. housing developments, and sports stadiums have been Global Sea-Level Rise built on fill that raised the land Following a few thousand level only a few feet above the years of relative stability, highest tides. The San Francisco International Airport (center) global sea level has been Sea-level change is linked and surrounding areas will begin to flood with as rising since the late 19th or to changes in the Earth’s little as 40 cm (16 inches) of sea-level rise, a early 20th century, when climate. -

Marine Snow Storms: Assessing the Environmental Risks of Ocean Fertilization

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Business and Law 1-1-2009 Marine snow storms: Assessing the environmental risks of ocean fertilization Robin M. Warner University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lawpapers Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Warner, Robin M.: Marine snow storms: Assessing the environmental risks of ocean fertilization 2009, 426-436. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lawpapers/192 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Marine snow storms: Assessing the environmental risks of ocean fertilization Abstract The threats posed by climate change to the global environment have fostered heightened scientific interest in marine geo-engineering schemes designed to boost the capacity of the oceans to absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide. This is the primary goal of a process known as ocean fertilization which seeks to increase the production of organic material in the surface ocean in order to promote further draw down of photosynthesized carbon to the deep ocean. This article describes the process of ocean fertilization, its objectives and potential impacts on the marine environment and some examples of ocean fertilization experiments. It analyses the applicability of international law principles on marine environmental protection to this process and the regulatory gaps and ambiguities in the existing international law framework for such activities. Finally it examines the emerging regulatory for legitimate scientific experiments involving ocean fertilization being developed by the London Convention and London Protocol Scientific Groups and its potential implications for the proponents of ocean fertilization trials. -

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

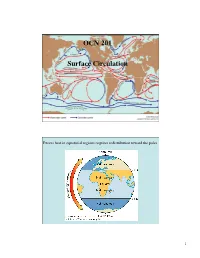

Surface Circulation2016

OCN 201 Surface Circulation Excess heat in equatorial regions requires redistribution toward the poles 1 In the Northern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the right In the Southern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the left Combination of atmospheric cells and Coriolis force yield the wind belts Wind belts drive ocean circulation 2 Surface circulation is one of the main transporters of “excess” heat from the tropics to northern latitudes Gulf Stream http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/Images/gulf_stream_modis_lrg.gif 3 How fast ( in miles per hour) do you think western boundary currents like the Gulf Stream are? A 1 B 2 C 4 D 8 E More! 4 mph = C Path of ocean currents affects agriculture and habitability of regions ~62 ˚N Mean Jan Faeroe temp 40 ˚F Islands ~61˚N Mean Jan Anchorage temp 13˚F Alaska 4 Average surface water temperature (N hemisphere winter) Surface currents are driven by winds, not thermohaline processes 5 Surface currents are shallow, in the upper few hundred metres of the ocean Clockwise gyres in North Atlantic and North Pacific Anti-clockwise gyres in South Atlantic and South Pacific How long do you think it takes for a trip around the North Pacific gyre? A 6 months B 1 year C 10 years D 20 years E 50 years D= ~ 20 years 6 Maximum in surface water salinity shows the gyres excess evaporation over precipitation results in higher surface water salinity Gyres are underneath, and driven by, the bands of Trade Winds and Westerlies 7 Which wind belt is Hawaii in? A Westerlies B Trade -

Chapter 8 the Pacific Ocean After These Two Lengthy Excursions Into

Chapter 8 The Pacific Ocean After these two lengthy excursions into polar oceanography we are now ready to test our understanding of ocean dynamics by looking at one of the three major ocean basins. The Pacific Ocean is not everyone's first choice for such an undertaking, mainly because the traditional industrialized nations border the Atlantic Ocean; and as science always follows economics and politics (Tomczak, 1980), the Atlantic Ocean has been investigated in far more detail than any other. However, if we want to take the summary of ocean dynamics and water mass structure developed in our first five chapters as a starting point, the Pacific Ocean is a much more logical candidate, since it comes closest to our hypothetical ocean which formed the basis of Figures 3.1 and 5.5. We therefore accept the lack of observational knowledge, particularly in the South Pacific Ocean, and see how our ideas of ocean dynamics can help us in interpreting what we know. Bottom topography The Pacific Ocean is the largest of all oceans. In the tropics it spans a zonal distance of 20,000 km from Malacca Strait to Panama. Its meridional extent between Bering Strait and Antarctica is over 15,000 km. With all its adjacent seas it covers an area of 178.106 km2 and represents 40% of the surface area of the world ocean, equivalent to the area of all continents. Without its Southern Ocean part the Pacific Ocean still covers 147.106 km2, about twice the area of the Indian Ocean. Fig. 8.1. The inter-oceanic ridge system of the world ocean (heavy line) and major secondary ridges. -

Marine Pollution: a Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime Lawrence R

Hastings Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 5 1-1972 Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime Lawrence R. Lanctot Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence R. Lanctot, Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime, 24 Hastings L.J. 67 (1972). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol24/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions-A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime By LAWRENCE R. LANCTOT* THE oceans are earth's last significant frontier for man's utiliza- tion. Advances in marine technology are opening previously unreach- able depths to permit the study of the oceans' mysteries and the extrac- tion of valuable natural resources.' Because these vast resources were inaccessible in the past, international law does not provide any certain rules governing the ownership and development of marine resources which lie beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.2 In response to this legal uncertainty and in the face of accelerating technology, the United Nations General Assembly has called a General Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1973 to formulate international conventions gov- erning the development of the seabed and ocean floor., Great interest * J.D., University of San Francisco, 1968; LL.M., Columbia University, 1969; Adjunct Professor of Law, University of San Francisco.