The Prophetic Laments of Samuel the Lamanite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Samuel the Lamanite

Samuel the Lamanite S. Michael Wilcox Samuel the Lamanite was the only Book of Mormon prophet identied as a Lamanite. Apart from his sermon at Zarahemla (Hel. 13—15), no other record of his life or ministry is preserved. Noted chiey for his prophecies about the birth of Jesus Christ, his prophetic words, which were later examined, commended, and updated by the risen Jesus (3 Ne. 23:9—13), were recorded by persons who accepted him as a true prophet and even faced losing their lives for believing his message (3 Ne. 1:9). Approximately ve years before Jesus’ birth, Samuel began to preach repentance in Zarahemla. After the incensed Nephite inhabitants expelled him, the voice of the Lord directed him to return. Climbing to the top of the city wall, he delivered his message unharmed, even though certain citizens sought his life (Hel. 16:2). Thereafter, he ed and “was never heard of more among the Nephites” (Hel. 16:8). Samuel prophesied that Jesus would be born in no more than ve years’ time, with two heavenly signs indicating his birth. First, “one day and a night and a day” of continual light would occur (Hel. 14:4; cf. Zech. 14:7). Second, among celestial wonders, a new star would arise (Hel. 14:5—6). Then speaking of mankind’s need of the atonement and resurrection, he prophesied signs of Jesus’ death: three days of darkness among the Nephites would signal his crucixion, accompanied by storms and earthquakes (14:14—27). Samuel framed these prophecies by pronouncing judgments of God upon his hearers. -

The Zarahemla Record September 1978

THEZARAHEMLA RECORD /ssueNumber 2 September 1978 "And he that witl not harden his heart, to him is given the greater portion of the word..." Alma 9: 18 The MORMON BOOKOF Endof JareditesArrive Jaredite Division and Culture of People- MESOAMERICAN OutlinesCompared: Beginning, Highpointsand Endings First Pottery Endof Olmec Maya Glyphs Appears Culture Begin By RaymondC. Treat The most importanttype of evidenceat the presenttime time range. The first pottery is clatedwithin this range. The so- supportingthe Bookof Mormonis a correlationof the outlines called Pox pottery from Puerto Marquez, Guerrero and the of the Book of Mormon and Mesoamericanarchaeology at Tehuacan Valley is dated 2300-2M B.C. and the newly strategic points along the approximately2800 years of their discovered Swasey pottery from Belize goes back to this time. common history. To understandthe reasonfor this it is Pottery is one of the most important types of evidence in necessaryto understandthat archaeologicalinformation is on- Mesoamericanarchaeology and the first appearanceof pottery ly partialinformation. Therefore, most archaeological informa- is always significant. Mesoamerica itself becomes known as a tion is subjectto morethan one interpretation.There is abun- culture area soon after the appearanceof pottery. dant evidencein Mesoamericanarchaeology supporting the Bookof Mormon,but in manycases a non-believercould offer Highpoint an opposinginterpretation to explainthe evidence.However, Archaeology necessarilydeals with physical things. Therefore the reconstructionof a long culturehistory is lesssubiect to in- an archaeologicalhighpoint is defined in terms of the quantity terpretationsince more data is gatheredto constructit than and quality of materialremains. Spiritual values of a culture are any other single type of archaeologicalevidence. This is much more difficult to detect. -

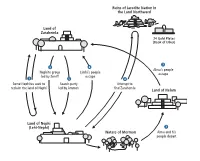

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

Conversion of Alma the Younger

Conversion of Alma the Younger Mosiah 27 I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. Mosiah 27:29 he first Alma mentioned in the Book of Mormon Before the angel left, he told Alma to remember was a priest of wicked King Noah who later the power of God and to quit trying to destroy the Tbecame a prophet and leader of the Church in Church (see Mosiah 27:16). Zarahemla after hearing the words of Abinadi. Many Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah fell people believed his words and were baptized. But the to the earth. They knew that the angel was sent four sons of King Mosiah and the son of the prophet from God and that the power of God had caused the Alma, who was also called Alma, were unbelievers; ground to shake and tremble. Alma’s astonishment they persecuted those who believed in Christ and was so great that he could not speak, and he was so tried to destroy the Church through false teachings. weak that he could not move even his hands. The Many Church members were deceived by these sons of Mosiah carried him to his father. (See Mosiah teachings and led to sin because of the wickedness of 27:18–19.) Alma the Younger. (See Mosiah 27:1–10.) When Alma the Elder saw his son, he rejoiced As Alma and the sons of Mosiah continued to rebel because he knew what the Lord had done for him. against God, an angel of the Lord appeared to them, Alma and the other Church leaders fasted and speaking to them with a voice as loud as thunder, prayed for Alma the Younger. -

Christmas in Zarahemla Written by Mary Ashworth & Tamara Fackrell

Christmas in Zarahemla Written by Mary Ashworth & Tamara Fackrell Narrator: From the dawn of Creation, mankind looked forward to the central event of the Holy Scriptures—the coming of the promised Messiah—the KING OF KINGS. The dispensations of Adam and Enoch, Noah, Abraham and Moses all kept and treasured this most precious message. A Redeemer would come to save the world from sin and error. The children of the covenant, those descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, made their way to Egypt in the time of famine, to find their brother Joseph in a position of power. There they flourished, and then became enslaved. At last the 400-year sojourn in Egypt came to an end with the mighty Proclamation of Moses, “Let my people go.” The Red Sea parted for these children of the covenant and they gave thanks for their escape. Arriving in the Promised Land, they built a Temple to the Most High God. For a thousand years they kept alive the treasured Word. The Law of Moses was their constant reminder of the coming of the Redeemer. Voice of Sariah: The prophet Isaiah Spoke: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son and shall call his name Immanuel. For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace. “(Isaiah 9:6) Choir: O Little Town of Bethlehem Narrator: The beautiful Temple of Solomon was destroyed by the invading Babylonians in 587 B.C. -

What Does the Book of Mormon Teach About Prophets?

What Does the Book of Mormon Teach about Prophets? “He ... cried with a loud voice, and prophesied unto the people whatsoever things the Lord put into his heart.” Helaman 13:4 KnoWhy # 284 March 8, 2017 Four Prophets by Robert T. Barrett via lds.org Principle When Samuel the Lamanite prophesied on the walls of to foretell coming events, to utter prophecies, which is Zarahemla, he spoke the words that “the Lord put into only one of the several prophetic functions.”1 A careful his heart” (Helaman 13:4). When the prophet Alma the look at the Book of Mormon shows, as Elder Widtsoe Younger met his soon-to-be companion, Amulek, he noted, that prophets do a lot more than tell the future. told him that he had “been called to preach the word of God among all this people, according to the spirit of Although about half of the references to prophets and revelation and prophecy” (Alma 8:24). Jacob, the son of prophecy in the Book of Mormon involve cases in which Lehi, said that he had “many revelations and the spirit the prophet was involved in telling about things to come, of prophecy” (Jacob 4:6). The Nephites often appointed they are often shown doing many other things as well.2 as their chief captains “some one that had the spirit of The prophet Alma, for example, was able to know the revelation and also prophecy” (3 Nephi 3:19). All told, thoughts of Zeezrom “according to the spirit of prophe- the Book of Mormon mentions prophets or prophecy cy” (Alma 12:7), an act of discerning the present rather over 350 times. -

Priesthood Concepts in the Book of Mormon

s u N S T O N E Unique perspectives on Church leadership and organi zation PRIESTHOOD CONCEPTS IN THE BOOK OF MORMON By Paul James Toscano THE BOOK OF MORMON IS PROBABLY THE EARLI- people." The phrasing and context of this verse suggests that est Mormon scriptural text containing concepts relating to boththe words "priest" and "teacher" were not used in our modern the structure and the nature of priesthood. This book, printed sense to designate offices within a priestly order or structure, between August 1829 and March 1830, is the first published such as deacon, priest, bishop, elder, high priest, or apostle. scripture of Mormonism but was preceded by seventeen other Nor were they used to designate ecclesiastical offices, such as then unpublished revelations, many of which eventually appearedcounselor, stake president, quorum president, or Church presi- in the 1833 Book of Commandments and later in the 1835 dent. They appear to refer only to religious functions. Possibly, edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. Prior to their publica- the teacher was one who expounded and admonished the tion, most or all of these revelations existed in handwritten formpeople; the priest ~vas possibly one who mediated between and undoubtedly had limited circulation. God and his people, perhaps to administer the ordinances of While the content of many of these revelations (now sec-the gospel and the rituals of the law of Moses, for we are told tions 2-18) indicate that priesthood concepts were being dis- by Nephi that "notwithstanding we believe in Christ, we keep cussed in the early Church, from 1830 until 1833 the Book the law of Moses" (2 Nephi 25: 24). -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS LETTERS viii ARTICLES • --David Eccles: A Man for His Time Leonard J. Arrington, 1 • --Leonard James Arrington (1917-1999): A Bibliography David J. Whittaker, 11 • --"Remember Me in My Affliction": Louisa Beaman Young and Eliza R. Snow Letters, 1849 Todd Compton, 46 • --"Joseph's Measures": The Continuation of Esoterica by Schismatic Members of the Council of Fifty Matthew S. Moore, 70 • -A LDS International Trio, 1974-97 Kahlile Mehr, 101 VISUAL IMAGES • --Setting the Record Straight Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 121 ENCOUNTER ESSAY • --What Is Patty Sessions to Me? Donna Toland Smart, 132 REVIEW ESSAY • --A Legacy of the Sesquicentennial: A Selection of Twelve Books Craig S. Smith, 152 REVIEWS 164 --Leonard J. Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian Paul M. Edwards, 166 --Leonard J. Arrington, Madelyn Cannon Stewart Silver: Poet, Teacher, Homemaker Lavina Fielding Anderson, 169 --Terryl L. -

Mosiah Like the Lamanites, Who Know Nothing King Benjamin Teaches Sons About God's Commandments and See Mosiah, Chapter 1 Mysteries

!139 A Plain English Reference to have faltered in unbelief. We would be The Book of Mosiah like the Lamanites, who know nothing King Benjamin teaches sons about God's commandments and See Mosiah, Chapter 1 mysteries. They don't believe these things because they are misguided by This peace among all the people in the their forefathers' false traditions. land of Zarahemla lasted for the rest of Remember this, for these records are King Benjamin's days. He had three true. sons, Mosiah, Helorum and Helaman, and taught them the writing language of And these plates Nephi made, which their forefathers — modified Egyptian. contain our forefathers' words from the time they left Jerusalem until now, are He did this so they would become men also true. Remember to search them of understanding, knowing the diligently so you may profit from them. prophecies the Lord had given their forefathers (engraved on Nephi's I want you to obey God’s commands plates). so you will prosper in the land, according to the promises He made to Benjamin also taught his sons our forefathers." concerning the records engraved on the brass plates, saying, King Benjamin taught many more things to his sons not written here. "My sons, I want you to remember, if it were not for these plates containing As he grew old and realized he would records and commandments, we would soon die, he felt it necessary to confer now be in ignorance, not knowing the the kingdom upon one of his sons. And mysteries of God. It would have been so he called for Mosiah, named after impossible for our forefather Lehi to his grandfather, and said to him, have remembered all these things, and "My son, I want you to make a to have taught them to his children proclamation throughout all the land of without these plates. -

How Can People Today Avoid Being Destroyed Like the Nephites Were? Four Hundred Years Pass Not Away Save

KnoWhy #327 June 16, 2017 Samuel at the Wall 2 by Jorge Cocco How Can People Today Avoid Being Destroyed Like the Nephites Were? Four hundred years pass not away save ... heavy destruction ... cometh unto this people, and nothing can save this people save it be repentance and faith on the Lord Jesus Christ. Helaman 13:5–6 The Know fas In August of 1830, Joseph discovered that a man named ing can save this people save it be repentance and faith Hiram Page had used a stone to receive two revelations on the Lord Jesus Christ” (Helaman 13:5–6, emphasis on behalf of the entire Church. Joseph was surprised to added).5 Four hundred years later, as destruction was find that so many people believed Page’s supposed reve- falling on the people, they apparently had not listened, lations and enquired of the Lord concerning the issue.1 as Mormon stated that the people no longer had any The response confirmed that “no one shall be appoint- faith (Moroni 8:14).6 ed to receive commandments and revelations in this church excepting my servant Joseph Smith, Jun.” (Doc- Samuel told the Nephites that if they continued to care trine and Covenants 28:2). Yet some continued to listen more about their riches than about the poor, the Lord to others rather than the prophet. Eventually, the Lord “curseth your riches, that they become slippery, that ye had to warn the church to “beware of pride, lest ye be- cannot hold them” (Helaman 13:31, emphasis added).7 come as the Nephites of old” (Doctrine and Covenants This kind of economic havoc is exactly what took place