Quest for a Hockey Franchise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How US Sports Financing and Recruiting Models Can Restore

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 42 Issue 1 Article 23 2009 Perfect Pitch: How U.S. Sports Financing and Recruiting Models Can Restore Harmony between FIFA and the EU Christine Snyder Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Recommended Citation Christine Snyder, Perfect Pitch: How U.S. Sports Financing and Recruiting Models Can Restore Harmony between FIFA and the EU, 42 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 499 (2009) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol42/iss1/23 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. PERFECT PITCH:HOW U.S. SPORTS FINANCING AND RECRUITING MODELS CAN RESTORE HARMONY BETWEEN FIFA AND THE EU Christine Snyder* When the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the world governing body for football, announced its plan to implement a new rule restricting the number of foreign players eligible to play for club teams the world over, the European Union took notice. Prior court rulings on a similar rule found that such a rule conflicts with the protection for the free movement of workers under the EC Treaty. Despite this conflict, the Presi- dent of FIFA pressed forward, citing three main justifications for implemen- tation of the new rule. This Note examines each of those justifications and proposes alternative solutions based on U.S. -

2018-19 Lehigh Valley Phantoms

2018-19 Lehigh Valley Phantoms Skaters Pos Ht Wt Shot Hometown Date of Birth 2017-18 Team(s) Gms G-A-P PIM 2 De HAAS, James D 6-3 212 L Mississauga, ON 5/5/1994 (24) Lehigh Valley 36 1-10-11 10 Reading (ECHL) 23 5-13-18 6 5 MYERS, Philippe D 6-5 202 R Moncton, NB 1/25/1997 (21) Lehigh Valley 50 5-16-21 54 6 SAMUELSSON, Philip D 6-2 194 L Leksand, Sweden 7/26/1991 (27) Charlotte (AHL) 76 4-17-21 48 7 PALMQUIST, Zach D 6-0 192 L South St. Paul, MN 12/9/1990 (27) Iowa (AHL) 67 6-28-34 42 9 BARDREAU, Cole C 5-10 193 R Fairport, NY 7/22/1993 (25) Lehigh Valley 45 11-19-30 59 10 CAREY, Greg F 6-0 204 L Hamilton, ON 4/5/1990 (28) Lehigh Valley 72 31-22-53 32 12 GOULBOURNE, Tyrell LW 6-0 200 L Edmonton, AB 1/26/1994 (23) Lehigh Valley 63 8-11-19 79 Philadelphia (NHL) 9 0-0-0 2 13 McDONALD, Colin RW 6-2 220 R Wethersfield, CT 9/30/1984 (34) Lehigh Valley 56 8-17-25 21 16 AUBE-KUBEL, Nic RW 5-11 196 R Sorel, PQ 5/10/1996 (22) Lehigh Valley 72 18-28-46 86 17 RUBTSOV, German C 6-0 187 L Chekhov, Russia 6/27/1998 (20) Chicoutimi (QMJHL) 11 3-8-11 0 Acadie-Bathurst (QMJHL) 38 12-20-32 19 FAZLEEV, Radel C 6-1 192 L Kazan, Russia 1/7/1996 (22) Lehigh Valley 63 4-15-19 24 21 VECCHIONE, Mike C 5-10 194 R Saugus, MA 2/25/1993 (25) Lehigh Valley 65 17-23-40 24 22 CONNER, Chris RW 5-7 181 L Westland, MI 12/23/1983 (34) Lehigh Valley 65 17-20-37 22 23 LEIER, Taylor LW 5-11 180 L Saskatoon, SASK 2/15/1994 (24) Philadelphia (NHL) 39 1-4-5 6 24 TWARYNSKI, Carsen LW 6-2 198 L Calgary, AB 11/24/1997 (20) Kelowna (WHL) 68 45-27-72 87 Lehigh Valley 5 1-1-2 0 25 BUNNAMAN, Connor F 6-1 207 L Guelph, ON 4/16/1998 (20) Kitchener (OHL) 66 27-23-50 31 26 VARONE, Phil C 5-10 186 L Vaughan, ON 12/4/1990 (27) Lehigh Valley 74 23-47-70 36 37 FRIEDMAN, Mark D 5-10 191 R Toronto, ON 12/25/1995 (22) Lehigh Valley 65 2-14-16 18 38 KAŠE, David F 5-11 170 L Kadan, Czech Rep. -

Springfield Hockey LLC Asks Fans to Help Name the Team

Springfield Hockey LLC Asks Fans to Help Name the Team Name the Team survey for the American Hockey League franchise to be conducted in partnership with the Springfield Republican and MassLive.com Wednesday, 06.1.2016 / 9:00 AM ET / News Springfield Hockey LLC, in partnership with the Springfield Republican and MassLive, is seeking fan suggestions for the name of the city’s new AHL franchise. The Name the Team online survey will run from Wednesday, June 1st at 5:00 AM until Friday, June 3rd at 12:00 PM. Fans can submit suggestions on the MassLive website by visiting www.MassLive.com/NameTheTeam. The team’s name will inspire the logo, uniforms, and branding for the organization. The team is looking for names that reflect the excitement and energy of a Springfield on the rise. The team will review all the entries and announce the winner in the coming weeks. “Our organization is deeply committed to community engagement. This is a fun and unique opportunity for hockey fans of all ages to get involved with the new team and we can’t wait to see all the creative names that they come up with,” said Attorney Frank Fitzgerald, spokesperson for the franchise. Springfield Hockey, LLC is a broad-based group of local investors committed to building an exciting and innovative brand of sports entertainment and maintaining professional hockey as a civic asset for the region. The franchise is the minor league affiliate of the Florida Panthers. The team will compete in the Atlantic Division of the AHL’s Eastern Conference and play its home games at the MassMutual Center in Springfield, Mass. -

Télécharger La Page En Format

Portail de l'éducation de Historica Canada Canada's Game - The Modern Era Overview This lesson plan is based on viewing the Footprints videos for Gordie Howe, Bobby Orr, Father David Bauer, Bobby Hull,Wayne Gretzky, and The Forum. Throughout hockey's history, though they are not presented in the Footprints, francophone players like Guy Lafleur, Mario Lemieux, Raymond Bourque, Jacques Lemaire, and Patrick Roy also made a significant contribution to the sport. Parents still watch their children skate around cold arenas before the sun is up and backyard rinks remain national landmarks. But hockey is no longer just Canada's game. Now played in cities better known for their golf courses than their ice rinks, hockey is an international game. Hockey superstars and hallowed ice rinks became national icons as the game matured and Canadians negotiated their role in the modern era. Aims To increase student awareness of the development of the game of hockey in Canada; to increase student recognition of the contributions made by hockey players as innovators and their contributions to the game; to examine their accomplishments in their historical context; to explore how hockey has evolved into the modern game; to understand the role of memory and commemoration in our understanding of the past and present; and to critically investigate myth-making as a way of understanding the game’s relationship to national identity. Background Frozen fans huddled in the open air and helmet-less players battled for the puck in a -28 degree Celsius wind chill. The festive celebration was the second-ever outdoor National Hockey League game, held on 22 November 2003. -

Our Online Shop Offers Outlet Nike Football Jersey,Authentic New Nike Jerseys,Nfl Kids Jersey,China Wholesale Cheap Football

Our online shop offers Outlet Nike Football Jersey,Authentic new nike jerseys,nfl kids jersey,China wholesale cheap football jersey,Cheap NHL Jerseys.Cheap price and good quality,IF you want to buy good jerseys,click here!ANAHEIM ?a If you see by the pure numbers,nfl stitched jerseys, Peter Holland??s fourth season surrounded the Ontario Hockey League didn?¡¥t characterize a drastic amendment from his third. Look beyond the numbers and you?¡¥ll find that?the 20-year-old center?took a significant step ahead. Holland amended his goal absolute with the Guelph Storm from 30 to 37 and his digit of points?from 79 to 88. The improvements are modest merely it is the manner he went almost it that has folk seeing him in a different light. The lack of consistency among his game has hung around Holland?¡¥s neck among junior hockey and the Ducks?¡¥ altitude elect surrounded 2009 was cognizant enough to acquaint that his converge prior to last season. ?¡ãThat?¡¥s kind of been flagged about me as the past pair of years immediately,nike new nfl jerseys,nfl custom jerseys,?¡À Holland said.??¡ÀObviously you go aboard the things that folk tell you to go on so I was trying to go on my consistency. I thought I did smart well this daily.?¡À ?¡ãThat comes with maturity also Being capable to activity the same game every night. It?¡¥s never a matter of being a 120 percent an night and 80 percen the?next. It?¡¥s almost being consistent at that 95-100 percent region.?¡À Looking after Holland said spending another season surrounded Guelph certified beneficial The long stretches where he went without points shrank to a minimum. -

Hartford Wolf Pack 2018-19 Roster As of 4/4/19

Hartford Wolf Pack 2018-19 Roster as of 4/4/19 Pos. Player Ht. Wt. Catch Birthplace Date of Birth Age 2017-18 Team(s) GP W L OT GAA 31 G HALVERSON, Brandon 6-4 209 L Traverse City, MI 3/29/96 23 NY Rangers (NHL) 1 0 0 0 4.80 Wolf Pack (AHL) 5 1 4 0 3.42 Greenville (ECHL) 24 8 11 3 3.74 35 G HUSKA, Adam 6-4 227 L Zvolen, Slovakia 5/12/97 21 Univ. of Connecticut 27 8 16 2 2.59 Pos. Player Ht. Wt. Shot Birthplace Date of Birth Age 2017-18 Team(s) GP G A Pts. PIM 6 D REGISTER, Matt 6-2 225 L Calgary, Alta. 9/2/89 29 Colorado (ECHL) 72 17 48 65 51 10 LW DMOWSKI, Ryan 6-1 205 L East Lyme, CT 3/18/97 22 UMass-Lowell (H-East) 35 11 11 22 12 11 LW GROPP, Ryan 6-3 187 L Kamloops, BC 9/16/96 22 Wolf Pack (AHL) 59 14 7 21 14 14 D CRAWLEY, Brandon 6-1 204 L Glen Rock, NJ 2/2/97 22 Wolf Pack (AHL) 64 2 3 5 99 15 RW BUTLER, Bobby 6-0 188 R Marlborough, MA 4/26/87 31 Milwaukee (AHL) 67 24 21 45 36 17 C JONES, Nick 5-11 189 R Edmonton, Alta. 6/2/96 22 U. North Dakota (NCHC) 34 15 15 30 16 18 RW ZERTER-GOSSAGE, Lewis 6-2 195 R Montreal, Que. 5/23/95 23 Harvard University (ECAC) 32 10 19 29 12 19 C FOGARTY, Steven 6-3 210 R Chambersburg, PA 4/19/93 25 NY Rangers (NHL) 1 0 0 0 2 Wolf Pack (AHL) 63 9 11 20 22 20 D WESLEY, Josh 6-3 195 R Hartford, CT 4/9/96 22 Charlotte (AHL) 17 0 1 1 10 Florida (ECHL) 21 0 4 4 12 21 C McBRIDE, Shawn 6-2 200 L Victoria, B.C. -

One Half of Canadians Are NHL Fans TORONTO

MEDIA INQUIRIES: Lorne Bozinoff, President [email protected] 416.960.9603 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE One half of Canadians are NHL fans TORONTO October 6th, 2014 Montreal Canadiens most popular team TORONTO OCTOBER 6th, 2014 ‐ In a random sampling of public opinion taken by the HIGHLIGHTS: Forum Poll™ among 1504 Canadians 18 years of age and older, just more than one half (53%) are NHL hockey fans, which may represent as many as 14 million fans Just more than one half across the country. Being a fan is most common to the youngest (60%), males (60%), (53%) are NHL hockey fans, the wealthiest ($100K to $250K ‐ 58%), in Alberta (62%) and among Conservative which may represent as voters (59%) and among those with children (58%). Although those who claim many as 14 million fans Canadian ethnic background are slightly more likely than others to be fans (56%), across the country. South Asians and those from the British Isles are also fans (53% and 54%, respectively ‐ caution: very small base sizes). Hockey fans are most likely to describe themselves as "regular fans who watch Most are regular fans, more than a tenth are extreme fans some games and know all the Hockey fans are most likely to describe themselves as "regular fans who watch some rules" (40%) and this may games and know all the rules" (40%) and this may represent close to 6 million represent close to 6 million viewers. Just more than a quarter are "part time fans who watch a few games and viewers. the playoffs" (27%, or about 4 million fans). -

2009-2010 Colorado Avalanche Media Guide

Qwest_AVS_MediaGuide.pdf 8/3/09 1:12:35 PM UCQRGQRFCDDGAG?J GEF³NCCB LRCPLCR PMTGBCPMDRFC Colorado MJMP?BMT?J?LAFCÍ Upgrade your speed. CUG@CP³NRGA?QR LRCPLCRDPMKUCQR®. Available only in select areas Choice of connection speeds up to: C M Y For always-on Internet households, wide-load CM Mbps data transfers and multi-HD video downloads. MY CY CMY For HD movies, video chat, content sharing K Mbps and frequent multi-tasking. For real-time movie streaming, Mbps gaming and fast music downloads. For basic Internet browsing, Mbps shopping and e-mail. ���.���.���� qwest.com/avs Qwest Connect: Service not available in all areas. Connection speeds are based on sync rates. Download speeds will be up to 15% lower due to network requirements and may vary for reasons such as customer location, websites accessed, Internet congestion and customer equipment. Fiber-optics exists from the neighborhood terminal to the Internet. Speed tiers of 7 Mbps and lower are provided over fiber optics in selected areas only. Requires compatible modem. Subject to additional restrictions and subscriber agreement. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Copyright © 2009 Qwest. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Joe Sakic ...........................................................................2-3 FRANCHISE RECORD BOOK Avalanche Directory ............................................................... 4 All-Time Record ..........................................................134-135 GM’s, Coaches ................................................................. -

Icehogs Monday, May 10 Chicago Wolves (11-17-1-0) 2 P.M

Rockford IceHogs Monday, May 10 Chicago Wolves (11-17-1-0) 2 p.m. CST (18-8-1-2) --- --- 23 points Triphahn Ice Arena Hoffman Estates, IL 39 points (6th, Central) Game #30, Road #14 Series 2-6-0-0 (1st, Central) WATCH: WIFR 23.2 Antenna TV, AHLTV ICEHOGS AT A GLANCE LISTEN: SportsFan Radio WNTA-AM 1330, IceHogs.com, SportsFanRadio1330.com Overall 11-17-1-0 Streak 0-2-0-0 Home 7-9-0-0 Home Streak 0-1-0-0 LAST GAME: Road 4-8-1-0 Road Streak 0-1-0-0 » Goaltender Matt Tomkins provided 29 key saves on Mother’s Day, but the Iowa Wild caught OT 3-1 Last 5 2-3-0-0 breaks late in the first period and early in the second for a 2-0 victory over the Rockford IceHogs at Shootout 2-0 Last 10 4-6-0-0 BMO Harris Bank Center Sunday afternoon. ICEHOGS LEADING SCORERS Player Goals Assists Points GAME NOTES Cody Franson 4 11 15 Hogs and Wild Celebrate Mother's Day and Close Season Series\ Dylan McLaughlin 4 9 13 The Rockford IceHogs and Iowa Wild closed their 10-game season series and two-game Mother's Evan Barratt 4 8 12 Day Weekend set at BMO Harris Bank Center on Sunday with the Wild skating away with a 2-0 vic- Chris Wilkie 6 5 11 tory. The IceHogs wrapped up the season series with a 4-5-1-0 head-to-head record. The matchup was the first time the IceHogs have played on Mother’s Day since 2008 in Game 6 of their second- 2020-21 RFD vs. -

The 1917 Allan Cup Championship

The 1917 Allan Cup Championship From January to February 1917 four teams strived for the championship of the Thunder Bay League who would then play for the Allan Cup against five other teams. The four Thunder Bay teams consisted of the 141st Battalion, Port Arthur, Fort William, and Schreiber. Whichever team won would then be playing from February to March 1917 for the Allan Cup, won by the 61st Winnipeg Battalion in 1916. Due to last year’s winner being overseas, they would be replaced by the Winnipeg Victorias and the 221st Winnipeg Battalion. Starting on January 1st of 1917, Port Arthur was up against Fort William in a very physical game of hockey. Fort William stayed in the lead since the beginning of the game, only giving Port Arthur one goal against them during the whole Port Arthur News Chronicle game, and won with a high score of 6-1. January 2, 1917 After Port Arthur took the win on the fourth, the 141st Battalion went head to head against Fort William, again keeping the score tied for most of the game. Luckily they did not have to go into overtime and instead, while Fort William had a lead of 3-2 in the third period of the game, the soldiers turned the play around and scored three more goals within nine minutes left of the game, ultimately defeating Fort William Three days after Port Arthur’s loss on the first they had to play the 141st Battalion in a racing fight to win. By third period they were tied 2-2 and were forced to go into overtime. -

Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 9 September 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 783016864] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Journal of the History of Sport Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713672545 Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson To cite this Article Wilson, JJ(2005) 'Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War', International Journal of the History of Sport, 22: 3, 315 — 343 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09523360500048746 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523360500048746 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

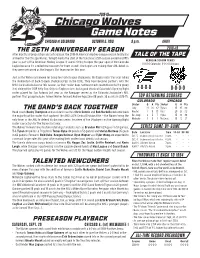

Chicago Wolves Game Notes

2018-19 !!!!!CHICAGO!WOLVES ! GAME!NOTES CHICAGO at COLORADO OCTOBER 5, 2018 8 p.m. AHLTV THE!=>TH!ANNIVERSARY!SEASON 2018-19 After months of preparation and anticipation, the 2018-19 American Hockey League season finally has TALE!OF!THE!TAPE arrived for the Chicago Wolves. Tonight marks the start of the franchise’s 25th season overall and 18th year as part of the American Hockey League. It seems fitting to open the year against the Colorado REGULAR-SEASON SERIES 0-0-0-0 Colorado | 0-0-0-0 Chicago Eagles because it’s a milestone occasion for them as well. The Eagles are making their AHL debut as they were welcomed as the league’s 31st team earlier this year. LAST MEETING April 22, 2018 Just as the Wolves are known for being four-time league champions, the Eagles enter this year riding the momentum of back-to-back championships in the ECHL. They have become partners with the NHL’s Colorado Avalanche this season, so their roster does not bear much resemblance to the group that claimed the 2018 Kelly Cup. Only six Eagles return, but a good chunk of Colorado’s Opening Night 0-0-0-0 0-0-0-0 roster played for San Antonio last year as the Rampage served as the Colorado Avalanche’s NHL partner. That group includes former Wolves forward Andrew Agozzino (18 goals, 36 assists in 2016-17). TOP RETURNING SCORERS COLORADO CHICAGO Skater G A Pts Skater G A Pts THE!BANDCS!BACK!TOGETHER Joly 41 26 67 Tynan 15 45 60 Head coach Rocky Thompson and assistant coaches Chris Dennis and Bob Nardella welcome back Nantel 4 11 15 Pirri 29 23 52 the majority of the roster that captured the AHL’s 2018 Central Division title -- the Wolves being the De Jong 2 5 7 Hyka 15 33 48 only team in the AHL to defend its division crown.