Re-Markings.Com RE-MARKINGS V O L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

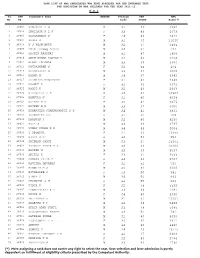

(*) Mere Assigning a Rank Does Not Confer Any Right to Select the Seat

RANK LIST OF MBA CANDIDATES WHO HAVE APPEARED FOR THE ENTRANCE TEST FOR ADMISSION TO MBA COLLEGES FOR THE YEAR 2011-12. M.B.A Sl CET Candidate Name GENDER Version CET MBA No. NO. Code SCORE Rank(*) 1 AC001 VANISHRI K S F A1 40 4392 2 AC003 SHAILAJA N L N F A3 43 2673 3 AC004 YASHASWINI S F A4 44 2422 4 AC005 SAGAR S M A1 32 11020 5 AC006 N J YESHWANTH M A2 37 6484 6 AC008 UMER FAROOQ AHMED M A4 61 124 7 AC009 SACHIN ARAKERI M A1 47 1408 8 AC010 ARUN KUMAR CHAVAN V M A2 43 2658 9 AC011 GUNDU YAMAGAR M A3 39 4960 10 AC014 KAVYASHREE S F A2 54 464 11 AC015 DHANANJAYA B M A3 34 9005 12 AC016 MADHU M M A4 37 6342 13 AC017 JHENKARA MANJUNATH F A1 43 2849 14 AC021 RASHMI R F A1 34 9371 15 AC022 RAMIT K M A2 43 2663 16 AC024 NIVEDITHA H C F A4 32 10807 17 AC025 MANJULA N F A1 40 4324 18 AC026 NAYANA M C F A2 41 3875 19 AC027 NAVEEN H M M A3 37 6600 20 AC028 BHARATESH CHAKRAVARTHI S B M A4 41 3821 21 AC029 PRAMEETHA PAI F A1 61 105 22 AC030 DARSHAN S M A2 40 4236 23 AC031 MALA S M A3 43 2747 24 AC032 VINAY KUMAR K N M A4 45 2004 25 AC033 G APOORVA F A1 30 12955 26 AC034 NAVYA S N F A2 53 554 27 AC035 SRIDHAR SADGI M A3 27 15261 28 AC036 PRADEEP KUMAR M K M A4 33 10106 29 AC038 NAVEEN M M A2 39 5037 30 AC039 ANITHA K F A3 37 6533 31 AC040 MANASA PRIYA H F A4 43 2767 32 AC041 KAVITHA DEVADAS F A1 51 726 33 AC042 MANOHAR M S M A2 42 3205 34 AC043 HITHASREE S F A3 50 941 35 AC044 VINAY G M A4 50 894 36 AC045 CHANDINI S M F A1 55 364 37 AC046 VIDYA R F A2 38 5592 38 AC047 THONTADARYA K V M A3 48 1281 39 AC048 DIVYA M F A4 40 4330 40 AC049 ANILKUMAR V M A1 31 12201 41 AC050 ADARSHA Y P M A2 38 5888 42 AC051 SHAIK ADAM SHAFI M A3 38 5685 43 AC052 VASUDHENDRA BADAMI M A4 51 781 44 AC053 SATEESH KUMAR M A1 40 4326 45 AC054 YASHASWINI Y K F A2 42 3311 46 AC055 ANROOP M A3 40 4430 47 AC056 SANJAY V M A4 29 13775 48 AC057 MADHURI CHANDRA V E F A1 37 6408 49 AC058 DEEPIKA T R F A2 43 2784 50 AC059 AMRUTHESH M M A3 46 1730 (*) Mere assigning a rank does not confer any right to select the seat. -

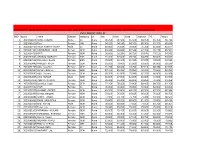

Evgc Result 2020-21

Guest teacher result for the post of EVGC for the session 2020-21(fresh vacancies) in r/o those applicants who filled the application form EVGC RESULT 2020-21 SNO appid name Gender category ph Sec SrSec Grad Diploma PG Result 1 2020028476 SUNIL KUMAR Male SC None 96.250 96.560 85.560 89.650 85.350 89.799 2 2020061620 Ritu Female OBC None 94.620 94.140 84.500 88.300 85.700 88.690 3 2020009413 VICKY KUMAR YADAV Male SC None 80.000 95.820 92.000 76.250 85.000 85.877 4 2020002142 HARSIMRAN KAUR Female GEN None 83.600 93.000 82.540 92.200 76.170 85.561 5 2020034430 KRITI Female GEN None 95.000 93.250 86.720 83.840 74.110 84.982 6 2020063541 APURVA BAJPAYEE Female EWS None 91.200 87.400 69.720 84.250 87.400 83.457 7 2020042552 Deepanky Gupta Female EWS None 79.000 92.400 81.590 87.970 74.000 83.191 8 2020050445 HARLEEN KAUR Female GEN None 85.500 78.400 81.800 83.600 86.800 83.190 9 2020051239 Aditi Kaushish Female GEN None 91.200 84.600 74.250 87.910 80.380 82.963 10 2020002007 Himani Bishnoi Female GEN None 87.400 85.250 78.550 93.200 72.600 82.950 11 2020039592 Aditi Sharma Female GEN None 89.300 81.000 73.940 82.200 86.000 81.968 12 2020032695 ANIL KUMAR Male GEN None 85.000 87.000 82.000 85.000 72.000 81.550 13 2020012376 ASMITA NAGPAL Female GEN None 89.300 95.200 68.000 80.050 79.100 81.358 14 2020058350 Sanchita Singh Female GEN None 72.200 78.600 73.900 89.400 84.550 81.208 15 2020047922 JYOTI Female SC None 90.000 92.000 78.000 70.000 82.000 81.000 16 2020039379 JASMINE OBEROI Female GEN None 85.500 67.800 84.170 80.500 87.500 80.944 -

Filmography Dilip Kumar – the Substance and the Shadow

DILIP KUMAR: THE SUBSTANCE AND THE SHADOW Filmography Year Film Heroine Music Director 1944 Jwar Bhata Mridula Anil Biswas 1945 Pratima Swarnlata Arun Kumar 1946 Milan Meera Mishra Anil Biswas 1947 Jugnu Noor Jehan Feroz Nizami 1948 Anokha Pyar Nargis Anil Biswas 1948 Ghar Ki Izzat Mumtaz Shanti Gobindram 1948 Mela Nargis Naushad 1948 Nadiya Ke Par Kamini Kaushal C Ramchandra 1948 Shaheed Kamini Kaushal Ghulam Haider 1949 Andaz Nargis Naushad 1949 Shabnam Kamini Kaushal S D Burman 1950 Arzoo Kamini Kaushal Anil Biswas 1950 Babul Nargis Naushad 1950 Jogan Nargis Bulo C Rani 1951 Deedar Nargis Naushad 1951 Hulchul Nargis Mohd. Shafi and Sajjad Hussain 1951 Tarana Madhubala Anil Biswas 1952 Aan Nimmi and Nadira Naushad 1952 Daag Usha Kiran and Nimmi Shankar Jaikishan 1952 Sangdil Madhubala Sajjad Hussain 1953 Footpath Meena Kumari Khayyam 1953 Shikast Nalini Jaywant Shankar Jaikishan 1954 Amar Madhubala Naushad 1955 Azaad Meena Kumari C Ramchandra 1955 Insaniyat Bina Rai C Ramchandra 1955 Uran Khatola Nimmi Naushad 1955 Devdas Suchitra Sen, Vyjayanti S D Burman Mala 1957 Naya Daur Vyjayantimala O P Nayyar 1957 Musafir Usha Kiran, Suchitra Salil Chaudhury Sen 1 DILIP KUMAR: THE SUBSTANCE AND THE SHADOW 1958 Madhumati Vyjayantimala Salil Chaudhury 1958 Uahudi Meena Kumari Shankar Jaikishan 1959 Paigam Vyjayantimala, B Saroja C Ramchandra Devi 1960 Kohinoor Meena Kumari Naushad 1960 Mughal-e-Azam Madhubala Naushad 1960 Kala Bazaar (Guest Appearance) 1961 Gunga Jumna Vyjayantimala Naushad 1964 Leader Vyjayantimala Naushad 1966 Dil Diya Dara Liya -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

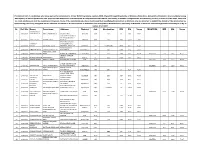

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

O Przygodach Bengalczyków W Indyjsko-Japońskim Ogrodzie Fikcji

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository Monika Browarczyk Uniwersytet Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu O przygodach Bengalczyków w indyjsko-japońskim ogrodzie fi kcji The Japanese Wife Aparny Sen i Kunala Basu Europejskie stereotypy na wyrafi nowanego kulturalnie erudytę i intelektuali- stę namaszczają Francuza; na subkontynencie indyjskim jego odpowiednikiem w obiegowej opinii jest Bengalczyk postrzegany jako przedstawiciel inteligen- cji i awangardy artystycznej – jeśli nie twórca, to choćby subtelny koneser sztuk. Źródła intelektualnego wysublimowania mieszkańców Bengalu indyj- ski – a szczególnie północnoindyjski vox populi, choć populi ogranicza się do niewielkiej stosunkowo grupy odbiorców kultury – odnajduje w pionierskim i bliskim kontakcie Bengalu z kulturą brytyjskich kolonizatorów. Kontakt ten inspirował twórców regionu do wprowadzenia nowatorskich przemian w róż- nych dziedzinach sztuki, co z kolei stało się natchnieniem dla artystów z innych części subkontynentu, zwłaszcza zaś właśnie z północy. W licznym panteonie wybitnych autorów bengalskich szczególne miejsce zajmują oddaleni od siebie w czasie Rabindranath Tagore (wym. Tagor) (1861−1941) i Satyajit Ray (wym. Satjadźit Raj) (1921−1992), którzy w swoich dziedzinach – literaturze i fi lmie1 – stali się rozpoznawanymi i docenianymi w całym świecie ikonami kultury nawet nie bengalskiej, ale indyjskiej2. Co więcej, Ray sięgał wielokrotnie do twórczości Rabindranatha Tagore’a, przekładając jego literaturę na swój własny język kina autorskiego. 1 Choć nie ograniczali się tylko do twórczości w jednej dyscyplinie. Ray pisał również opo- wiadania i powieści, a Rabindranath Tagore, najsławniejszy indyjski poeta, był także powieściopi- sarzem, nowelistą, dramaturgiem, eseistą, kompozytorem i malarzem. Por. Elżbieta Walter, Wpro- wadzenie, w: Rabindranath Tagore. Poeta świata, red. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

24012004 Dt Mpr 01 D L C

DLD‰‰†‰KDLD‰‰†‰DLD‰‰†‰MDLD‰‰†‰C THE TIMES OF INDIA Janet Jackson find your first name Saturday, to music buffs: January 24, 2004 I’m All For You! initial here Bottom-pinching ghost scares women Page 11 In this case, it’s hint of its presen- back to the basics ce,’’ claims Suza- for an entirely nne Botsch, a vic- ‘supernatural’ re- tim, ‘‘I have bru- ason. Here are ises to prove that the ‘scary’ detai- I was attacked.’’ ls: women in a Fr- A local magist- ench town have rate maintains taken to wearing that ‘‘the inciden- padded underwe- ts are for real.’’ ar after reports of attacks Town residents are main- by a sharp-clawed ghost taining all-night vigils ho- who pinches the bottoms of ping to catch the phantom its victims. in the act. After all, every- ‘‘The ghost crept up beh- body feels the pinch when a ind me without giving any town is host to a ghost. OF INDIA DABBAWALLAS TO IIM: WORDS OF BIZDOM MANOJ KESHARWANI Mumbai’s famous dabbawallas share the secrets of their success with students of 50 management institutes at a seminar hosted by IIM-Lucknow JYOTHI PRABHAKAR long-term business enterprises.’’ is excited by the knowledge he gained at the sem- cision. The modus operandi involves a dab- Times News Network During the seminar, management students inar: ‘‘It is the dream of any management stu- bawalla leaving lunch-boxes collected individu- learnt how dabbawallas dent to learn from the ex- ally from homes at the nearest railway station. heir clockwork precision and manageri- have not only managed to LEARNING EXPERIENCE perience of those who From here, the boxes go through a series of tran- al skills left Prince Charles impressed. -

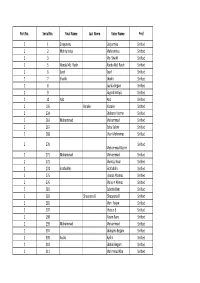

55 Nagpur Central Panchnama List.Xlsx

Part No. Serial No. Final Name Last Name Voter Name Prof 2 1 Sirajunnisa Sirajunnisa Shifted 2 2 Mehrunnisa Mehrunnisa Shifted 2 3 Mo. Sheikh Shifted 2 5 Abeda Md. Raish Abeda Md. Raish Shifted 2 6 Syed Syed Shifted 2 7 Shaikh Shaikh Shifted 2 8 Sayida Begam Shifted 2 9 Sayyad Imtiyaj Shifted 2 10 Aziz Aziz Shifted 2 105 Korake Korake Shifted 2 234 Shabana Yasmin Shifted 2 261 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 267 Babu Salam Shifted 2 268 Khan Mohmmad Shifted 2 270 Shifted Mohammad Bashir 2 271 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 272 Mumtaj Noor Shifted 2 274 Sirafuddin Sirafuddin Shifted 2 275 Isharat Ahamad Shifted 2 276 Maisum Ahmad Shifted 2 281 Zubeda Bano Shifted 2 283 Shaqeena B Shaqeena B Shifted 2 285 Moh. Faijan Shifted 2 297 Khatun B Shifted 2 298 Nasim Bano Shifted 2 299 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 307 Shahjaha Begam Shifted 2 309 Aysha Aysha Shifted 2 310 Shahin Begam Shifted 2 311 Mohmmad Kha Shifted 2 312 Jubeda B Shifted 2 313 Mahajbin Mahajbin Shifted 2 314 Ayyub Ayyub Shifted 2 315 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 316 Yakub Kha Shifted 2 317 Mahbub Kha Shifted 2 318 Sheikh Ilati Shifted 2 325 Kaji Jaibunnisa Shifted 2 326 Kaji Vahid Shifted 2 327 Moh. Aslam Shifted 2 328 Shaheda Begum Shaheda Begum Shifted Mohammad Aslam Mohammad Aslam 2 329 Shirin Bano Shifted 2 330 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 333 Sadeeq Ulla Khan Sadeeq Ulla Khan Shifted Shahnajbano Shahnajbano 2 334 Shifted Sadikaulla Kha Sadikaulla Kha 2 335 Sabeer Ulla Khan Sabeer Ulla Khan Shifted 2 336 Shifted Atiya Kausar Sadeeq Atiya Kausar Sadeeq 2 337 Shifted Ullah Ullah Faridabano Sazid Faridabano Sazid 2 339 Shifted Ahmed Khan Ahmed Khan 2 340 Jabir Akhtar Shifted 2 341 Imran Kha Shifted 2 342 Shifted Shahin Afroz Sadeeq Shahin Afroz Sadeeq 2 346 Jabin Akhtar Jabin Akhtar Shifted 2 347 Raisa Parvin Raisa Parvin Shifted 2 348 Raisa Parvin Raisa Parvin Shifted 2 361 Farida Begam Shifted Nazma Anzum Yunus Nazma Anzum Yunus 2 364 Shifted Khan Khan 2 388 Moh. -

Hindi DVD Database 2014-2015 Full-Ready

Malayalam Entertainment Portal Presents Hindi DVD Database 2014-2015 2014 Full (Fourth Edition) • Details of more than 290 Hindi Movie DVD Titles Compiled by Rajiv Nedungadi Disclaimer All contents provided in this file, available through any media or source, or online through any website or groups or forums, are only the details or information collected or compiled to provide information about music and movies to general public. These reports or information are compiled or collected from the inlay cards accompanied with the copyrighted CDs or from information on websites and we do not guarantee any accuracy of any information and is not responsible for missing information or for results obtained from the use of this information and especially states that it has no financial liability whatsoever to the users of this report. The prices of items and copyright holders mentioned may vary from time to time. The database is only for reference and does not include songs or videos. Titles can be purchased from the respective copyright owners or leading music stores. This database has been compiled by Rajiv Nedungadi, who owns a copy of the original Audio or Video CD or DVD or Blu Ray of the titles mentioned in the database. The synopsis of movies mentioned in the database are from the inlay card of the disc or from the free encyclopedia www.wikipedia.org . Media Arranged By: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Lifeline/762365430471414 © 2010-2013 Kiran Data Services | 2013-2015 Malayalam Entertainment Portal MALAYALAM ENTERTAINMENT PORTAL For Exclusive -

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’S Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy)

Anil Biswas – Filmography Source: Hamraz’s Hindi Film Geet Kosh (Digitization: Ketan Dholakia, Vinayak Gore, and Balaji Murthy) Contents Anil Biswas – Filmography ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1) Dharam Ki Devi ..................................................................................................................... 3 2) Fida-e-Vatan (alias Tasveer-e-vafa) ...................................................................................... 3 3) Piya Ki Jogan (alias Purchased Bride) ................................................................................... 3 4) Pratima (alias Prem Murti) ..................................................................................................... 4 5) Prem Bandhan (alias Victims of Love) .................................................................................. 4 6) Sangdil Samaj ......................................................................................................................... 4 7) Sher Ka Panja ......................................................................................................................... 5 8) Shokh Dilruba ......................................................................................................................... 5 9) Bulldog ................................................................................................................................... 5 10) Dukhiari (alias A Tale of Selfless Love) -

PORTRAYAL of SEXUAL MINORITIES in HINDI FILMS By

Articles Global Media Journal – Indian Edition/ISSN 2249-5835 Sponsored by the University of Calcutta/ www.caluniv.ac.in Summer Issue / June 2012 Vol. 3/No.1 PORTRAYAL OF SEXUAL MINORITIES IN HINDI FILMS Sanjeev Kumar Sabharwal Assistant Professor Amity School of Communication Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow Campus, Uttar Pradesh, India Website: http://www.amity.edu/lucknow Email:[email protected] and Reetika Sen Academic Coordinator Amity School of Communication Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow Campus, Uttar Pradesh, India Website: http://www.amity.edu/lucknow Email: [email protected] Abstract: Sexual minority or Alternative sexuality comprises of all those people who fall under the categories of Gay, Lesbian, Transgender, Eunuchs. This paper basically compares the portrayal of sexual minorities in Mainstream and Alternative Hindi Cinema. It talks about how Mainstream Hindi cinema which is the most widely distributed cinema in India and abroad has traditionally adopted an attitude of denial or mockery towards LGBTQ community. Representations of sexual Minorities have veered between the sarcasm, comic and the criminal. Where as Alternative Cinema which is confined to film festivals and a handful selected group of viewers portrays sexual minorities in more realistic manner and is successful in raising, expressing & suggesting possible solutions to their problems in more effective manner as compared to the main stream cinema. This is a qualitative as well as quantitative research and the methodology adopted to find out the answers to the questions is content analysis of four Hindi films and survey. Two films of mainstream and two of alternative cinema were selected randomly. Both secondary and primary data was collected, from various reliable sources like journals, websites, articles, movie reviews of different newspapers etc.