Evaluation of Community-Based Conservation Approaches: Management of Protected Areas in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

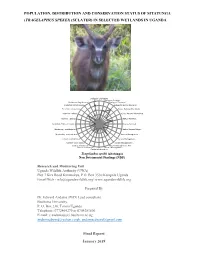

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching | Chimpreports

5.7.2021 Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching | ChimpReports News Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching Arafat Nzito • July 4, 2021 1 minute read Two Rwandese nationals identified as Habimana Sabanitah and Sobomana Augustine have been sentenced to 12 years in jail for illegal entry and killing of protected wildlife species. The two, both residents of Rwamwanja refugee settlement in Kamwenge district, were found in possession of a dead bush buck inside Katonga Wildlife Reserve. LUISA CERANO - Long-Cardigan aus Mohair-Mix - 34 - braun - Damen Luisa Cerano | Sponsored By using this website, you agree that we and our partners may set cookies for purposes such as customisingRead Next Scontenttory and advertising.TranslateI Understand » https://chimpreports.com/two-rwandese-nationals-sentenced-to-12-years-in-jail-for-poaching/ 1/7 5.7.2021 Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching | ChimpReports According to the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), the two were arrested on June 28, 2021 by UWA personnel inside Katonga Wildlife Reserve. “They were found in possession of a dead bush buck, 2 pangas, 2 sharp spears and 8 wire snares that were used to kill the animal,” UWA stated. Upon arrest, the suspects were transferred to Kyegegwa police station and later produced before the Chief Magistrate’s Court of Kyenjojo to take plea. The accused pleaded guilty to the counts as charged of illegal entry and killing a protected wildlife species. Prosecution led by Latif Amis argued that the two deprived the wider public and national economy the benefits of conservation including tourism, employment and foreign exchange earnings. -

Important Bird Areas in Uganda. Status and Trends 2008

IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS IN UGANDA Status and Trends 2008 NatureUganda The East Africa Natural History Society Important Bird Areas in Uganda Status and Trends 2008 Compiled by: Michael Opige Odull and Achilles Byaruhanga Edited by: Ambrose R. B Mugisha and Julius Arinaitwe Map illustrations by: David Mushabe Graphic designs by: Some Graphics Ltd January 2009 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non commercial purposes is authorized without further written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Production of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written notice of the copyright holder. Citation: NatureUganda (2009). Important Bird Areas in Uganda, Status and Trends 2008. Copyright © NatureUganda – The East Africa Natural History Society About NatureUganda NatureUganda is a Non Governmental Organization working towards the conservation of species, sites and habitats not only for birds but other taxa too. It is the BirdLife partner in Uganda and a member of IUCN. The organization is involved in various research, conservation and advocacy work in many sites across the country. These three pillars are achieved through conservation projects, environmental education programmes and community involvement in conservation among others. All is aimed at promoting the understanding, appreciation and conservation of nature. For more information please contact: NatureUganda The East Africa Natural History Society Plot 83 Tufnell Drive, Kamwokya. P.O.Box 27034, Kampala Uganda Email [email protected] Website: www.natureuganda.org DISCLAIMER This status report has been produced with financial assistance of the European Union (EuropeAid/ ENV/2007/132-278. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of Birdlife International and can under no normal circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. -

RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where Science Comes to Life

RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where science comes to life Contents Knowing 2 Introducing the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science and an explanation of how and why the RSPB does science. A decade of science at the RSPB 9 A selection of ten case studies of great science from the RSPB over the last decade: 01 Species monitoring and the State of Nature 02 Farmland biodiversity and wildlife-friendly farming schemes 03 Conservation science in the uplands 04 Pinewood ecology and management 05 Predation and lowland breeding wading birds 06 Persecution of raptors 07 Seabird tracking 08 Saving the critically endangered sociable lapwing 09 Saving South Asia's vultures from extinction 10 RSPB science supports global site-based conservation Spotlight on our experts 51 Meet some of the team and find out what it is like to be a conservation scientist at the RSPB. Funding and partnerships 63 List of funders, partners and PhD students whom we have worked with over the last decade. Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) Conservation rooted in know ledge Introduction from Dr David W. Gibbons Welcome to the RSPB Centre for Conservation The Centre does not have a single, physical Head of RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Science. This new initiative, launched in location. Our scientists will continue to work from February 2014, will showcase, promote and a range of RSPB’s addresses, be that at our UK build the RSPB’s scientific programme, helping HQ in Sandy, at RSPB Scotland’s HQ in Edinburgh, us to discover solutions to 21st century or at a range of other addresses in the UK and conservation problems. -

Proposal for Uganda

AFB.PPRC.27-28.2 AFB/PPRC.26-27/2 21 June 2021 Adaptation Fund Board Project and Programme Review Committee PROPOSAL FOR UGANDA AFB/PPRC.27-28/2 Background 1. The Operational Policies and Guidelines (OPG) for Parties to Access Resources from the Adaptation Fund (the Fund), adopted by the Adaptation Fund Board (the Board), state in paragraph 45 that regular adaptation project and programme proposals, i.e. those that request funding exceeding US$ 1 million, would undergo either a one-step, or a two-step approval process. In case of the one-step process, the proponent would directly submit a fully-developed project proposal. In the two-step process, the proponent would first submit a brief project concept, which would be reviewed by the Project and Programme Review Committee (PPRC) and would have to receive the endorsement of the Board. In the second step, the fully-developed project/programme document would be reviewed by the PPRC, and would ultimately require the Board’s approval. 2. The Templates approved by the Board (Annex 5 of the OPG, as amended in March 2016) do not include a separate template for project and programme concepts but provide that these are to be submitted using the project and programme proposal template. The section on Adaptation Fund Project Review Criteria states: For regular projects using the two-step approval process, only the first four criteria will be applied when reviewing the 1st step for regular project concept. In addition, the information provided in the 1st step approval process with respect to the review criteria for the regular project concept could be less detailed than the information in the request for approval template submitted at the 2nd step approval process. -

Vote:022 Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Antiquities

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:022 Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Antiquities QUARTER 4: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q4 by End Q 4 End Q4 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 2.086 1.043 2.086 1.989 100.0% 95.3% 95.3% Non Wage 7.259 3.621 6.775 6.765 93.3% 93.2% 99.9% Devt. GoU 6.082 2.783 5.470 5.470 89.9% 89.9% 100.0% Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% GoU Total 15.426 7.447 14.330 14.224 92.9% 92.2% 99.3% Total GoU+Ext Fin 15.426 7.447 14.330 14.224 92.9% 92.2% 99.3% (MTEF) Arrears 0.364 0.364 0.364 0.364 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% Total Budget 15.790 7.811 14.694 14.588 93.1% 92.4% 99.3% A.I.A Total 85.005 0.033 154.197 83.589 181.4% 98.3% 54.2% Grand Total 100.795 7.843 168.892 98.177 167.6% 97.4% 58.1% Total Vote Budget 100.431 7.479 168.528 97.813 167.8% 97.4% 58.0% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 1901 Tourism, Wildlife Conservation and 95.02 163.47 92.78 172.0% 97.6% 56.8% Museums Program: 1949 General Administration, Policy and Planning 5.41 5.06 5.04 93.5% 93.0% 99.5% Total for Vote 100.43 168.53 97.81 167.8% 97.4% 58.0% Matters to note in budget execution Although the approved budget for the Vote was Ushs 100.4 billion, a total of Ushs 168 billion was realized/released. -

Guidelines for Biodiversity Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes

Natural Resource Use and Management Series No. 14 Guidelines for Biodiversity Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes 2014 1 Guidelines for Biodiversity Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes 2 Natural Resource Use and Management GUIDELINES FOR BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPES Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non commercial purposes is authorized only with further written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Production of this publication for resale or other commer- cial purposes is prohibited without prior written notice of the copyright holder. Citation: NatureUganda, Tree Talk, Tropical Biology Association (2014), Guidelines for Biodiversity Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes in Uganda, NatureUganda, Tree Talk, Tropical Biology Association. Copyright ©NatureUganda – The East Africa Natural History Society Bwindi Mgahinga Conservation Trust (BMCT) Building Plot 1 Katalima Crescent, Lower Naguru P.O.Box 27034, Kampala Uganda Email: [email protected] Website: www.natureuganda.org Twitter: @NatureUganda Facebook: NatureUganda i Guidelines for Biodiversity Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Guidelines to Conservation of Biodiversity in Agricultural Landscapes were produced with funding from the British American Tobacco Biodiversity Partnership (BATBP) under the project ‘Addressing sustainable management for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in tobacco growing regions of Uganda’. This project is coordinated by Tropical -

Uganda Wildlife Assessment PDFX

UGANDA WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING REPORT ASSESSMENT APRIL 2018 Alessandra Rossi TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Reproduction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organisations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published by: TRAFFIC International David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK © TRAFFIC 2018. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN no: UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Suggested citation: Rossi, A. (2018). Uganda Wildlife Trafficking Assessment. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Front cover photographs and credit: Mountain gorilla Gorilla beringei beringei © Richard Barrett / WWF-UK Tree pangolin Manis tricuspis © John E. Newby / WWF Lion Panthera leo © Shutterstock / Mogens Trolle / WWF-Sweden Leopard Panthera pardus © WWF-US / Jeff Muller Grey Crowned-Crane Balearica regulorum © Martin Harvey / WWF Johnston's three-horned chameleon Trioceros johnstoni © Jgdb500 / Wikipedia Shoebill Balaeniceps rex © Christiaan van der Hoeven / WWF-Netherlands African Elephant Loxodonta africana © WWF / Carlos Drews Head of a hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius © Howard Buffett / WWF-US Design by: Hallie Sacks This report was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. -

Payment for Ecosystems Services: a Pathway for Environmental Conservation in Uganda

Payment for Ecosystems Services: A Pathway for Environmental Conservation in Uganda BY DR. EMMANUEL KASIMBAZI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, SCHOOL OF LAW, MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Ecosystems in Uganda • Uganda is gifted by nature, its geographical location has endowed it with a range of geographical features which range from glacier topped mountains, tropical rain forests, and dry deciduous acacia bush lands, to vast lakes and rivers, wetlands as well as fertile agricultural landscapes. • It was called the Pearl of Africa by the Britain’s World War II Prime minister, Sir Winston Churchill on his visit in 1907 to Uganda and was attracted to the magnificent scenery (landscape), wildlife and friendly natives (culture). To him, the beauty of it all could only be described as a pearl. Structure of the Presentation 1. Introduction: Ecosystems in Uganda 2. What is payment of ecosystems Services (PES) 3. Some benefits of PES 4. Legal and Policy Framework for Implementing PES 5. Some Projects that Implementing PES 6. The Challenges of Implementing in PES to conserve the Environment 7. Conclusion and strategies for PES to achieve environmental conservation Map of Uganda What is payment of ecosystems Services (PES)? PES is a product of an ecosystem service where there is a buyer such as companies, governments or an organization that is able and willing to pay for the conservation of the specific ecosystem service and there must be a seller or provider such as local communities, receiving a financial resource, who, in exchange, must promise to maintain that ecosystem service. Types of PES There are various types of PES. • Carbon sequestration and storage. -

Republic of Uganda Giraffe Conservation Status Report

Country Profile Republic of Uganda Giraffe Conservation Status Report Sub-region: East Africa General statistics Size of country: 236,040 km² Size of protected areas / percentage protected area coverage: 8% (Sub)species Rothschild’s giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi) Conservation Status IUCN Red List (IUCN 2012): Giraffa camelopardalis (as a species) – Least Concern Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi – Endangered In the Republic of Uganda: In the Republic of Uganda (referred to as Uganda in this report), giraffe are protected under the Game (Preservation and Control) Act of 1959 (Chapter 198). Giraffe are listed under Part A of the First Schedule of the Act as animals that may not be hunted or captured in Uganda. Issues/threats Uganda is home to the Rothschild’s giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi), one of the most imperilled giraffe (sub)species remaining in the wild. Illegal hunting, agricultural expansion, human encroachment, and habitat degradation, fragmentation and destruction have led to the extirpation of Rothschild’s giraffe from almost all of its former range (GCF 2013; USAID 2011; Fennessy & Brenneman 2010; Sidney 1965). Only a few small and isolated populations of Rothschild’s giraffe remain in Uganda (and Kenya), all of which are now confined to national parks and other protected areas (GCF 2013; Fennessy & Brenneman 2010). In the 1960s, wildlife numbers and diversity in Uganda was high, roaming freely both inside and outside of protected areas in the country (Rwetsiba & Nuwamanya 2010; Olupot et al. 2009; Rwetsiba & Wanyama 2005). The breakdown of rule and law in the country during the 1970s and early 1980s resulted in large- scale illegal hunting for bush meat by starving local people and soldiers, causing a significant decease of wildlife numbers, including giraffe (Rwetsiba et al. -

12 Day Primates & Predators

Uganda is a unique destination offering a wonderful mix of savannah and forest parks. Gorilla and chimp tracking are highlights, but many smaller primates can be seen as well. Uganda also offers great savannah safaris, but not all of the Big Five are present. Black rhino is extinct, and the status of the white rhino was the same until they were reintroduced in Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary in 2005. Cheetah is very rarely seen. Lion is quite common in Queen Elizabeth and Murchison Falls national parks. They can often be found hunting Uganda kob, which gives them away with their alarm calls. Giraffe can only be found in Murchison Falls, Lake Mburo and Kidepo Valley national parks, while zebra exists only in Kidepo and Lake Mburo national parks and Katonga wildlife reserve. Uganda is also a prime birding destination. You will see most of these species at some point in this wonderful full coverage itinerary throughout Uganda 12 Day Primates & Predators ITINERARY UGANDA Day 1: Monday 15 July 2019 Today, you will be collected from Entebbe Airport and transferred to Hotel No 5 for one night. Approximate driving time: 30 mins Accommodation at No.5 Boutique Hotel Ltd in a Luxury Double Room on a bed and breakfast basis for 1 night. In : Monday 15-Jul-2019 Out : Tuesday 16-Jul-2019 Nestled in the leafy suburbs of Entebbe, Hotel No.5 is a stylish boutique hotel. From the moment you arrive, you are warmly welcomed and cared for. With just ten luxury rooms and five apartments, many opening onto the garden and swimming pool, this is a great option for guests looking for an intimate stay in a tranquil setting. -

Uganda's Kibale National Park

Natural Resources and Environmental Issues Volume 7 University Education in Natural Resources Article 20 1998 Education's role in sustainable development: Uganda's Kibale National Park R. J. Lilieholm Department of Forest Resources, Utah State University, Logan K. B. Paul Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Lincoln University, Jefferson City, MO T. L. Sharik Department of Forest Resources, Utah State University, Logan R. Loether East Africa Studies Abroad, Durango, CO Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/nrei Recommended Citation Lilieholm, R. J.; Paul, K. B.; Sharik, T. L.; and Loether, R. (1998) "Education's role in sustainable development: Uganda's Kibale National Park," Natural Resources and Environmental Issues: Vol. 7 , Article 20. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/nrei/vol7/iss1/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources and Environmental Issues by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lilieholm et al.: Education's role in sustainable development EDUCATION’S ROLE IN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: UGANDA’S KIBALE NATIONAL PARK R.J. Lilieholm, K.B. Paul, T.L. Sharik, and R. Loether1 1 The authors are, respectively, Associate Professor, Department of Forest Resources, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5215 USA; Professor, Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Lincoln University, Jefferson City, MO 65101, USA; Professor and Head, Department of Forest Resources, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5215 USA; and Owner, East Africa Studies Abroad, P.O. Box 253, Durango, CO 81302 USA.