Decathlon Training Concepts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESULTS 400 Metres Hurdles Women - Final

Doha (QAT) 27 September - 6 October 2019 RESULTS 400 Metres Hurdles Women - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 29 Doha 4 Oct 2019 Championships Record CR 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 29 Doha 4 Oct 2019 World Leading WL 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 29 Doha 4 Oct 2019 Area Record AR National Record NR Personal Best PB Season Best SB 4 October 2019 21:29 START TIME 26° C 61 % TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 7 Feb 90 6 52.16 WR 0.200 2 Sydney MCLAUGHLIN USA 7 Aug 99 4 52.23 PB 0.161 3 Rushell CLAYTON JAM 18 Oct 92 5 53.74 PB 0.137 4 Lea SPRUNGER SUI 5 Mar 90 9 54.06 NR 0.199 5 Zuzana HEJNOVÁ CZE 19 Dec 86 8 54.23 0.141 6 Ashley SPENCER USA 8 Jun 93 2 54.45 (.444) 0.163 7 Anna RYZHYKOVA UKR 24 Nov 89 3 54.45 (.445) SB 0.173 8 Sage WATSON CAN 20 Jun 94 7 54.82 0.186 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE 2019 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD (USA) Doha 4 Oct 19 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD (USA) Doha 4 Oct 52.23 Sydney MCLAUGHLIN (USA) Doha 4 Oct 19 52.23 Sydney MCLAUGHLIN (USA) Doha 4 Oct 52.34 Yuliya PECHONKINA (RUS) Tula (Arsenal Stadium) 8 Aug 03 53.11 Ashley SPENCER (USA) Des Moines, IA (USA) 28 Jul 52.42 Melaine WALKER (JAM) Berlin (Olympiastadion) 20 Aug 09 53.73 Shamier LITTLE (USA) Lausanne (Pontaise) 5 Jul 52.47 Lashinda DEMUS (USA) Daegu (DS) 1 Sep 11 53.74 Rushell CLAYTON (JAM) Doha 4 Oct 52.61 Kim BATTEN (USA) Göteborg (Ullevi Stadium) 11 Aug 95 54.06 Lea SPRUNGER (SUI) Doha 4 Oct 52.62 Tonja -

A Proposal to Change the Women's Hurdles Events by Sergio Guarda

VIEWPOINT Ptrgi -i^^ by l/V\F 8:2; 23-26. 1993 A proposal to change the 1 Introduction women's hurdles events The Sprint hurdles race, more or less, as we now know it. was 'invented' at Oxford University in 1864. The dislance was 12(1 by Sergio Guarda Etcheverry yards, with an approach and finish of 15 yards and a 10 yards spacing between 10 hurdles, 3 foot 6 inches in height. These measurements formed the basis for the event when it was included in the firsi modern Olympic Games, held at Athens in 1896. There, measurements became the metric equivalents. 1 Ul metres dislance. 10 hurdles 106.7cm in height and 9.14 metres apart, a dislance from starl line lo first hurdle of 13.72 metres and from lasl hurdle to finish of 14.02 meires. The first gold medal for the Olympic event was won by Thomas Curtis (USA) wilh a lime of 17 •V5 sec. From thai dale to the present, the rules of this event have noi been modified despite the progress made in lhe construc tion of the hurdles, in the quality of the track surface, in the quality of the shoes, in the selection of lhe athletes and in the spe cific training methodology and planning. Thc 400 metres Hurdles for men was incorporated in the programme for lhe Sergio Guarda Etcheverry is a professor 1900 Olympic Games, held in Paris. The of phvsical education al the Ufiivcisiiy of winner on this firsl occasion was Waller Santiago. Chile, andanteinberofihe Tewksbury (USA) with a time of 57.6 sec. -

HEEL and TOE ONLINE the Official Organ of the Victorian Race Walking

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2019/2020 Number 40 Tuesday 30 June 2020 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours: Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 VRWC COMPETITION RESTARTS THIS SATURDAY Here is the big news we have all been waiting for. Our VRWC winter roadwalking season will commence on Saturday afternoon at Middle Park. Club Secretary Terry Swan advises the the club committee meet tonight (Tuesday) and has given the green light. There will be 3 Open races as follows VRWC Roadraces, Middle Park, Saturday 6th July 1:45pm 1km Roadwalk Open (no timelimit) 2.00pm 3km Roadwalk Open (no timelimit) 2.30pm 10km Roadwalk Open (timelimit 70 minutes) Each race will be capped at 20 walkers. Places will be allocated in order of entry. No exceptions can be made for late entries. $10 per race entry. Walkers can only walk in ONE race. Multiple race entries are not possible. Race entries close at 6PM Thursday. No entries will be allowed on the day. You can enter in one of two ways • Online entry via the VRWC web portal at http://vrwc.org.au/wp1/race-entries-2/race-entry-sat-04jul20/. We prefer payment by Credit Card or Paypal within the portal when you register. Ignore the fact that the portal says entries close at 10PM on Wednesday. -

The Olympics and Economics 2012 Contents

The Olympics and Economics 2012 Contents The Olympics and Economics 2012 .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Interview with Michael Johnson ............................................................................................................................................ 2 (Sprinter, four-time Olympic gold medallist and world record holder) Impact on the UK: 2012 Olympics Likely to Provide Economic As Well As Sporting Benefits ..................................... 4 Interview with Matthew Syed .................................................................................................................................................. 6 (Journalist, author and table tennis champion and a two-time Olympian) Gold Goes Where Growth Environment Is Best—Using Our GES to Predict Olympic Medals .................................... 8 Interview with Tim Hollingsworth ......................................................................................................................................... 12 (Chief Executive of the British Paralympic Association) Summer Olympics and Local House Prices: The Cases of Los Angeles and Atlanta ................................................... 14 The Olympics as a Winning FX Strategy ............................................................................................................................... 16 Impact of Olympics on Stock Markets .................................................................................................................................. -

Women's 400 Metres

Games of the XXXII Olympiad • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 400 Metres Entrants: 51 Event starts: August 3 Age (Days) Born SB PB 1066 OBOYA Bendere AUS 21y 103d 2000 51.61 51.21 -19 2019 Oceanian Champion // 200 pb: 24.33 -19 (24.91 -21). 1 Commonwealth Youth Games 2017; ht COM 2018; 1 Oceanian 2019; sf WCH 2019. 1 Australian 2021. Born- Gambela (Ethiopia), her family came to Australia in 2003. Coach-John Quinn In 2021: 4 Sydney Illawong 200; 1 Wollongong; 1 Australian Capital Territory; 1 Sydney; 1 New South Wales State; 1 Sydney Classic; 1 Melbourne Track Classic; 1 Brisbane Classic; 1 Australian; 1 Gold Coast Oceania Mixed 4x400; 1 Townsville; 1 Gold Coast Winter Series #1 200/400; 1 Cairns 1112 WALLI Susanne AUT 25y 85d 1996 51.99 51.99 -21 13x Austrian Champion at 400m (8 in + 5 out) // 200 pb: 23.54 -21. sf World Youth 2013; 8 WJC 2014; ht EIC 2019/2021; 1 Balkan 2021. 1 Austrian 2017-2021. 1 indoor 2013/2014/2015/2016/2018/2019/2020/2021 (1 indoor 200 2014/2016/2019/2020/2021) In 2021: 3 Vienna T&F; 2 Ostrava Czech Indoor Gala ‘B’; 7 Linz 60 (Feb 6); 4 Linz 60 (Feb 13); 1 Vienna ‘Road to Toruń’; 1 Austrian indoor 200/400; 4ht EIC; 1ht Linz 300; 3 Šamorín PTS; 1 Austrian Clubs 100; 6 Chorzów Kusocinski; 1 Austrian; 1 Balkan; 1 Linz 200; 1 Graz 200 1131 MILLER-UIBO Shaunae BAH 27y 106d 1994 49.08 48.37 -19 NR 2016 Olympic 400m Champion after a memorable finish versus Allyson Felix (then another memorable finish in London 2017, for different reasons) 200 pb: 21.74 -19 (22.03 -21). -

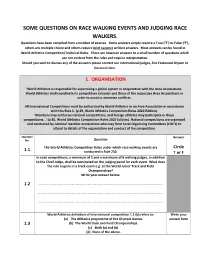

Some Questions on Race Walking Events and Judging Race Walkers

SOME QUESTIONS ON RACE WALKING EVENTS AND JUDGING RACE WALKERS. Questions have been compiled from a number of sources. Some answers simply require a True (‘T’) or False (‘F’), others are multiple choice and others require brief succinct written answers. Most answers can be found in World Athletics Competition/Technical Rules. There are however answers to a small number of questions which are not evident from the rules and require interpretation. Should you wish to discuss any of the answers please contact our international judges, Zoe Eastwood-Bryson or Kirsten Croker. 1. ORGANISATION ‘World Athletics is responsible for supervising a global system in cooperation with the Area Associations. World Athletics shall coordinate its competition calendar and those of the respective Area Associations in order to avoid or minimise conflicts. All International Competitions must be authorised by World Athletics or an Area Association in accordance with this Rule 1. (p 29, World Athletics Competition Rules 2020 Edition). ‘Members may authorise national competitions, and foreign athletes may participate in those competitions…’ (p 30, World Athletics Competition Rules 2020 Edition). National competitions are organised and conducted by national member associations who may form Local Organising Committees (LOC’s) to attend to details of the organisation and conduct of the competition. Question Answer Question No. The World Athletics Competition Rules under which race walking events are Circle 1.1 conducted is Rule 230. T or F In road competitions, a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 8 walking judges, in addition to the Chief Judge, shall be nominated on the judging panel for each event. -

OFSAA Track & Field Records

OFSAA Track & Field Records - Midget Boys EVENT RECORD NAME SCHOOL TOWN OR CITY YEAR SET 100 metres ET 10.89 Keith Dormond Graham B. Warren JHS North York 1981 200 metres ET 22.28 Marcus Renford Tommy Douglas SS Woodbridge 2017 400 metres ET 49.82 Ian Butcher Bishop Reding HS Milton 2002 400 metres ET 49.35 Dillon Landon Thousand Islands SS Brockville 2017 800 metres ET 1:53.24 Kevin Sullivan North Park C & VS Brantford 1989 1500 metres ET 3:54.31 Kevin Sullivan North Park C & VS Brantford 1989 3000 metres HT 8:40.3 Chris Brewster Catholic Central HS London 1979 3000 metres ET 8:47.94 Thomas Witkowicz All Saints CSS Whitby 2015 100 m hurdles (0.838 m) ET 13.26 Jermain Martinborough Pickering HS Pickering 1997 100 m hurdles (0.838 m) ET 13.41 Liam Mather London Central SS London 2015 300 m hurdles (0.838 m) ET 39.12 Jermain Martinborough Pickering HS Pickering 1997 300 m hurdles (0.838 m) ET 39.79 Mark Skerl Cardinal Newman Hamilton 2018 4 x 100 m relay ET 43.90 Jalon Rose, Jadon Rose Our Lady of Mt Carmel SS Mississauga 2018 Jaden Amoroso, Adam Magdziak High jump 2.04 m Michael Ponikvar Denis Morris HS St. Catharines 1995 High jump 1.95 m Jeff Webb Eden High School St. Catharines 2007 Pole vault 4.45 m Drew Barrett King City SS King City 1992 Pole vault 3.75 m Joel Mueller Ridgeway-Crystal Beach HS Ridgeway 2012 Long jump 6.79 m Bobby Lewelleyn George Harvey CI York 1986 Long jump 6.67 m Marcus Renford Tommy Douglas SS Woodbridge 2017 Triple jump 14.17 m Devon Davis Pickering HS Pickering 1994 Triple jump 14.17 m Kriss Peterson Sandwich -

Issue No: 380 February/March 2018 Editor

Issue No: 380 February/March 2018 Editor: Dave Ainsworth AWARD FOR ESSEX OFFICIAL For a second time, Loughton's hard working Pauline Wilson (Centurion 798) received the trophy as "Enfield League Official-of-the-Year" having helped out at 9 of their 2017 events. An honour truly deserved. The presentation was made by former Centurions' President Carl Lawton (C750) after the opening race of the League's 2018 series, held at Enfield's Queen Elizabeth II Stadium on a cold Saturday afternoon (20 January). RACE WALKING ASSOCIATION AGM This was held for a first time in the Clubhouse at Pingles Stadium - home of Nuneaton Harriers Athletic Club, which has a floodlit 8-lane 400 metres' all- weather track. Attendance at this delayed AGM was 22 and, during a business-like meeting, they elected a new President - International Judge Noel Carmody of Cambridge Harriers and an esteemed Metropolitan Police AA Life Member. The Vice President's post remained blank, so is to be looked at by the General Committee - any suggestions? If so, please speak up. The following positions were unopposed: Chairman: Glyn Jones Hon Championships Secretary: Peter Marlow Hon General Secretary: Colin Vesty Coaching & Development: Mark Wall Hon Treasurer: Mark Easton Press & Publicity Officer: John Constandinou International Chair: Pam Ficken Hon Auditor: John Elrick A position of Minutes Secretary wasn't filled when Chris Flint stepped down after many years of diligent service - Colin Vesty has taken on this duty along with his General Secretary's role. Ron Wallwork MBE, active in race walking since 1958, the inaugural Commonwealth Games gold medallist in 1966 (Jamaica) and now a successful Enfield League Organiser was elected an RWA Life Member - most deserved! ALBERT DAVID LEVY RIP - Notification from Mrs Gill Levy I am so sad to have to tell you that David passed away - much sooner than we anticipated. -

ABSTRACT Show an Overshoot Following a 400 Metre Run. However, the Overshoot Was Relatively Larger and More Long-Lived Following

62 Brit.J.Sports Med. - Vol. 20, No. 2 June 1986, pp. 62-65 HEART RATE OVERSHOOT IN RUNNING EVENTS K. YAMAJI, PhD* and R. J. SHEPHARD, MD, PhD** Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.20.2.62 on 1 June 1986. Downloaded from *Faculty ofEducation, Toyama University, Toyama City, Japan **School of Physical and Health Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada ABSTRACT The phenomenon of heart rate overshoot has been examined in 6 high-school athletes aged 15-16 years and in 8 university athletes aged 19-20 years. The incidence was 100% over distances of 50, 100 and 200 metres, and only one subject failed to show an overshoot following a 400 metre run. However, the overshoot was relatively larger and more long-lived following the shorter runs. While an accumulation of anaerobic metabolites seems the most likely explanation of the phenomenon over the longer distances, in the 50 metre event the Valsalva manoeuvre may also make some contribution. Key words: Heart rate, Overshoot, Valsalva manoeuvre, Lactate accumulation, Isometric exercise, Isotonic exercise. INTRODUCTION their school. The latter had trained 2 to 3 times per week for Yamaji and Shephard (1985) previously demonstrated that 2-5 years as members of the track and field club at their the threshold intensity of effort needed to cause a post- university, but were not elite sprinters. Physical exercise overshoot of heart rate was as low as 140 beats/ characteristics and track times are summarised in Table 1. min in some subjects. The incidence of overshoot increased with loading, reaching 65% with maximum aerobic work Exercise bouts. -

Men's 200 Metres

Games of the XXXII Olympiad • Biographical Entry List • Men Men’s 200 Metres Entrants: 57 Event starts: August 3 Age (Days) Born SB PB * 1136 GARDINER Steven BAH 25y 321d 1995 20.24 19.75 -18 NR 2019 World Champion // 400 pb: 43.87 -18 (44.47 -21). sf WJC 200 2014 (6 4x400); sf WCH 400 2015; sf OLY 400 2016 (3 4x400); 2 WCH 400 2017 (but no relay medal as Bahamas were eliminated in the heats having rested Gardiner). 1 Bahamian 400 2015/2016/2017/2019/2021. Coach-Gary Evans. 1.96 tall In 2021: 1 Carolina 200; (all 400) 1 Gainesville Tom Jones Olympic; dnf Fort Worth US F&F Open; 1 Nashville Music City Carnival; 1 Bahamian; 1 Székesfehérvár Gyulai 1153 BURKE Mario BAR 24y 134d 1997 20.08 20.08 -19 3x Barbadian Champion at 100m // 100 pb: 9.95w, 9.98 -19 (10.32 -21). 5 World Youth 100 2013; 3 WJC 100 2016; qf WCH 100 2017/2019; 3 North/Central American & Caribbean under-23 100 2019. 1 Barbadian 100 2017/2018/2019. 1 NCAA 4x100 2017/2018 & 2 NCAA indoor 60 2019, representing the University of Houston In 2021: 6 Texas Relays invitational 100 (5 200 ‘B’); 3 Prairie View Sprint Summit 100; 4 Miramar Invitational 100 ‘B’; 7 Austin Texas Invitational 100 ‘B’; 7 Houston Tom Tellez Invitational 100; 4 Clermont FL ‘Pure Summer’ 100; 2 Barbadian 100; 8ht Marietta Stars & Stripes 100 1203 VANDERBEMDEN Robin BEL 27y 170d 1994 21.08 20.43 -18 World, European & European indoor relay medals // 20.40w -18 (21.22i -21). -

State Records – April 2013

STATE RECORDS as at April 2013 (E) = Electronic Record UNDER 7 GIRLS Event Name Centre Performance Date 50 Metres Annette Cavanagh Blacktown 8.0 24-Mar-79 Andrea Parker Hills District 8.0 24-Mar-79 50 Metres (E) Alannah Martin Doonside 9.01 4-Mar-12 70 Metres Karolyn Cassidy Hills District 10.8 11-Mar-78 Jo-anne Swan Camden 10.8 16-Mar-80 100 Metres Belinda Ruiz Lake Illawarra 15.9 7-Mar-82 100 Metres (E) Montana Monk Wallsend RSL 17.50 6-Mar-11 200 Metres Jo-anne Swan Camden 33.1 15-Mar-80 Long Jump Sally Eggleton Ku-Ring-Gai 3.60m 21-Feb-82 Belinda Jones Hornsby 3.60m 21-Feb-82 Shot Put (1kg) Kylie Standing Bankstown 8.01m 20-Mar-83 Discus (350gm) Mallory Bassett Hornsby 21.24m 3-Mar-07 UNDER 7 BOYS Event Name Centre Performance Date 50 Metres Scott Weaver Scully Park 7.4 12-Mar-77 50 Metres (E) James Apostolakis Illawong 8.96 6-Mar-11 Lachlan Herbert Ku-Ring-Gai 8.96 3-Mar-13 70 Metres Graham Garnett Hornsby 10.8 18-Mar-73 Jonathon Weaver Scully Park 10.8 11-Mar-78 Adam Davis Greystanes 10.8 25-Mar-79 Jeffrey Poulter Bankstown 10.8 16-Mar-80 100 Metres Alan Powderly Walcha 15.4 7-Mar-82 100 Metres (E) James Apostolakis Illawong 17.30 6-Mar-11 Kalani Vella Albion Park 17.30 3-Mar-13 200 Metres Enzo Granata Holroyd 32.6 19-Mar-83 Long Jump Mark Lever Hornsby 3.71m 5-Feb-77 Greg Hammond Hornsby 3.71m 21-Mar-81 Shot Put (1kg) Blake Toohey Sutherland 10.20m 7-Mar-10 Discus (350gm) Anthony Krkovski Port Hacking 23.09m 5-Mar-05 UNDER 8 GIRLS Event Name Centre Performance Date 70 Metres Annette Cavanagh Blacktown 10.3 16-Mar-80 70 Metres (E) -

Jamie Baulch Visited Stawell in 1999

PEOPLE OF PRO RUNNING - By David Griffin The Richest professional footrace in the world has long been an attraction for international sprinters. Adding colour and prestige to the time-honoured event, the road to Stawell is well worn by athletes from faraway lands trying their luck. One of the great Stawell Gift wins by an international athlete came in 1975 when two-time Olympian Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa from Madagascar flew down the track from the scratch mark. Warren Edmondson from the US won in 1977, and who can forget the Scottish flyer George McNeil winning in 1981 after ten attempts. There have been others of course but overall, the grass and handicaps of Australia’s premier gift has been a tough nut to crack for the visitors. Olympic stars like John Drummond, Asafa Powell, Kim Collins, Michael Frater and Obedele Thompson found the going tough on the cosy confines of Central Park. English Olympian Jamie Baulch visited Stawell in 1999. The quarter mile specialist was fresh off his win in the 1999 world indoor 400 metre championships and was in Australia training with Olympic 100 metre gold medallist Linford Christie. Baulch was part of an elite British travelling group that included the ‘who’s who’ of British athletics. Now living in Cardiff, the Welsh 46-year-old reflects on the Stawell Gift weekend and his only professional race in Australia. EPISODE 12: JAMIE BAULCH “I was in Australia training with Colin Jackson, Linford Christie and Darren Campbell and the rest of the group. We decided to stay and train in Australia for three months.