A Holistic Aboriginal Framework for Individual Healing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOSM Activity Report Dr

NOSM Activity Report Dr. Roger Strasser, Dean-CEO January-February 2019 NOSM Announces Incoming Dean and CEO Dr. Sarita Verma appointed as Medical School’s next leader. The Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) is pleased to announce the appointment of Dr. Sarita Verma as Dean and CEO of NOSM effective July 1, 2019. The NOSM Board of Directors unanimously approved the appointment on December 12, 2018. “We are thrilled to welcome Dr. Verma to NOSM and to the wider campus of Northern Ontario,” says Dr. Pierre Zundel, Chair of the NOSM Board of Directors and Interim President and Vice Chancellor of Laurentian University. “Dr. Verma’s passion, vision and experience will continue to propel NOSM toward world leadership in distributed, community-engaged and socially accountable medical education.” Dr. Verma is currently Vice President, Education at the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC) and until January 2016, was Associate Vice-Provost, Relations with Health Care Institutions and Special Advisor to the Dean of Medicine at the University of Toronto. Formerly the Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Medicine (2008-2015) and Associate Vice-Provost, Health Professions Education (2010- 2015), she is a family physician who originally trained as a lawyer at the University of Ottawa (1981) and later completed her medical degree at McMaster University (1991). “I’m grateful to the Board for the opportunity to lead this incredible medical school, and honoured to continue with the momentum created in the past 15 years,” says Dr. Sarita Verma. “I am deeply committed to serving the people of Northern Ontario, to leading progress in Indigenous and Francophone health and cultivating innovation in clinical research.” Dr. -

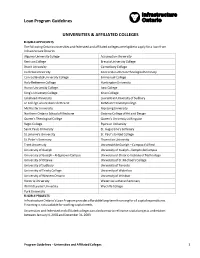

Loans Guidelines

Loan Program Guidelines UNIVERSITIES & AFFILIATED COLLEGES ELIGIBLE APPLICANTS The following Ontario universities and federated and affiliated colleges are eligible to apply for a loan from Infrastructure Ontario: Algoma University College Assumption University Renison College Brescia University College Brock University Canterbury College Carleton University Concordia Lutheran Theological Seminary Conrad Grebal University College Emmanuel College Holy Redeemer College Huntington University Huron University College Iona Coll ege King’s University College Knox College Lakehead University Laurentian University of Sudbury Le Collège universitaire de Hearst McMaster Divinity College McMaster University Nipissing University Northern Ontario School of Medicine Ontario College of Art and Design Queen’s Theological College Queen’s University at Kingston Regis College Ryerson University Saint Pauls University St. Augustine’s Seminary St. Jerome’s University St. Paul’s United College St. Peter’s Seminary Thorneloe University Trent University Université de Guelph – Campus d’Alfred University of Guelph University of Guelph – Kemptville Campus University of Guelph – Ridgetown Campus University of Ontario Institute of Technology University of Ottawa University of St. Michael’s College University of Sudbury University of Toronto University of Trinity College University of Waterloo University of Western Ontario University of Windsor Victoria University Waterloo Lutheran Seminary Wilfrid Laurier University Wycliffe College York University ELIGIBLE PROJECTS -

Crown Controlled Corporations

EXHIBIT THREE Crown Controlled Corporations CORPORATIONS WHOSE ACCOUNTS ARE AUDITED BY AN AUDITOR OTHER THAN THE PROVINCIAL AUDITOR, WITH FULL ACCESS BY THE PROVINCIAL AUDITOR TO AUDIT REPORTS, WORKING PAPERS AND OTHER RELATED DOCUMENTS Art Gallery of Ontario Crown Foundation Baycrest Hospital Crown Foundation Big Thunder Sports Park Ltd. Board of Funeral Services Brock University Foundation Carleton University Foundation CIAR Foundation (Canadian Institute for Advanced Research) Canadian Opera Company Crown Foundation Canadian Stage Company Crown Foundation Dairy Farmers of Ontario Deposit Insurance Corporation of Ontario Education Quality and Accountability Office Foundation at Queen’s University at Kingston Grand River Hospital Crown Foundation Lakehead University Foundation Laurentian University of Sudbury Foundation McMaster University Foundation McMichael Canadian Art Collection Metropolitan Toronto Convention Centre Corporation 38 Office of the Provincial Auditor Moosonee Development Area Board Mount Sinai Hospital Crown Foundation National Ballet of Canada Crown Foundation Nipissing University Foundation North York General Hospital Crown Foundation Ontario Casino Corporation Ontario Foundation for the Arts Ontario Hydro Sevices Company Inc. Ontario Mortgage Corporation Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement Board Ontario Pension Board Ontario Power Generation Inc. Ontario Superbuild Corporation Ontario Trillium Foundation Ottawa Congress Centre Royal Botanical Gardens Crown Foundation Royal Ontario Museum Royal Ontario Museum Crown -

French at the University of Ottawa Volume II State of Affairs for Programs and Services in French

University of Ottawa French at the University of Ottawa Volume II State of Affairs for Programs and Services in French Task Force on Programs and Services in French September 2006 www.uOttawa.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 3 2. CURRENT CONTEXT ................................................................. 4 3. UNIVERSITY ENVIRONMENT ..................................................... 6 Profile of university officials.............................................................................. 6 Profile of faculty.............................................................................................. 7 Profile of support staff ..................................................................................... 7 4. ACADEMIC PROGRAMS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA ............ 9 Language of instruction in undergraduate programs ............................................ 9 Language of instruction in undergraduate courses..............................................11 Small-group undergraduate courses .................................................................12 Graduate studies ...........................................................................................13 Immersion programs and courses ....................................................................14 Cooperative education programs......................................................................15 5. RECRUITMENT ACTIVITIES AND SCHOLARSHIPS ....................... 17 Recruitment -

Student Transitions Project WebBased Resources

Ontario Native Education Counselling Association Student Transitions Project WebBased Resources Index Section Content Page 1 Schools and Education Institutions for First Nations, Inuit and Métis 3 ‐ Alternative Schools ‐ First Nations Schools ‐ Post‐Secondary Institutions in Ontario 2 Community Education Services 5 3 Aboriginal Student Centres, Colleges 6 4 Aboriginal Services, Universities 8 5 Organizations Supporting First Nations, Inuit and Métis 11 6 Language and Culture 12 7 Academic Support 15 8 For Counsellors and Educators 19 9 Career Support 23 10 Health and Wellness 27 11 Financial Assistance 30 12 Employment Assistance for Students and Graduates 32 13 Applying for Post‐Secondary 33 14 Child Care 34 15 Safety 35 16 Youth Voices 36 17 Youth Employment 38 18 Advocacy in Education 40 19 Social Media 41 20 Other Resources 42 This document has been prepared by the Ontario Native Education Counselling Association March 2011 ONECA Student Transitions Project Web‐Based Resources, March 2011 Page 2 Section 1 – Schools and Education Institutions for First Nations, Métis and Inuit 1.1 Alternative schools, Ontario Contact the local Friendship Centre for an alternative high school near you Amos Key Jr. E‐Learning Institute – high school course on line http://www.amoskeyjr.com/ Kawenni:io/Gaweni:yo Elementary/High School Six Nations Keewaytinook Internet High School (KiHS) for Aboriginal youth in small communities – on line high school courses, university prep courses, student awards http://kihs.knet.ca/drupal/ Matawa Learning Centre Odawa -

APC071017-6.2 University of Windsor Academic Policy Committee

APC071017-6.2 University of Windsor Academic Policy Committee 6.2: University of Windsor’s Grading Scale (Background) Item for: Information Rationale: See attached Page 1 of 9 Received by Senate March 21, 2002 Sa020321-7.5.2.3 7.5.2.3: APC Working Group Report on Re-Evaluation of the University=s Grading Scale Item for: Information Forwarded by: Academic Policy Committee Following the Academic Policy Committee=s appointment of working groups, the Working Group on Evaluating the University=s Grading Scale, consisting of Professor Jeff Berryman, Dr. Sirinimal Withane, Ms. Cathy Maskell and Mr. Jerry McCorkell first met on Tuesday, the 16th of October, 2001 in the Faculty of Law. In addition to the Committee members, Ms. Charlene Yates of the Registrar=s Office was seconded to the Committee to assist it. The Committee members wish to record their thanks to Ms. Yates for her diligence and assistance. At the first meeting of the Committee, the terms of reference were discussed. The main issue placed before the Working Group was to investigate whether the current 13 point grade scale, and corresponding letter grades, used by the University of Windsor disadvantaged our students when applying to graduate programs or other scholarship opportunities. In particular, the Working Group was asked to determine whether there was a widely adopted scale and grading scheme used by other Universities in Canada and North America. It was suggested to the Working Group that the four-point scale is used by more universities in Canada and North America, and that scholarship granting agencies and graduate programs are more familiar with this scale and can therefore make comparisons if student applicants come from a wide variety of academic disciplines as well as universities. -

Understanding Indigenous Canadian Traditional Health and Healing

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2008 Understanding Indigenous Canadian Traditional Health and Healing (Gus) Louis Paul Hill Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Hill, (Gus) Louis Paul, "Understanding Indigenous Canadian Traditional Health and Healing" (2008). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1050. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1050 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING INDIGENOUS CANADIAN TRADITIONAL HEALTH AND HEALING By: (Gus) Louis Paul Hill MSW (Wilfrid Laurier University, 2001) BSW - Native Human Services (Laurentian University, 2000) DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of Social Work In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree Wilfrid Laurier University 2008 © (Gus) Louis Paul Hill 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38005-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38005-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde -

Point-Of-Sale Tax Exemption Stays in Place

Page 1 Volume 22 Issue 5 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 JUNE 2010 Point-of-sale tax exemption stays in place UOI OFFICES –The good news is that First Nations have won a hard- fought battle to retain their point-of-sale tax exemption in Ontario, says Anishinabek Nation Grand Council Chief Patrick Madahbee. "But our concern is that in this day and age we should be put in a situation where we are negotiating our treaty and inherent rights. We are allies of the Crown - not subjects. And we will continue to insist that Canada uphold their own court rulings that they must consult us and ac- commodate our interests in all matters that affect us and our traditional territories." Madahbee praised citizens of the 40 Anishinabek Nation communi- ties for their steadfast resistance to government efforts to impose the new 13% Harmonized Sales tax against them effective July 1. "It was our demonstrations of solidarity and plans for more peace- Whitefish River gift ful direct action that convinced Canada they should not cross the line On behalf of Whitefish River First Nation, council member George Francis presented Grand Council Chief we drew in the sand," said Madahbee. "My most sincere thanks to our Patrick Madahbee with a mounted eagle during the annual general assembly of the Anishinabek Nation in Fort Elders, men, women and youth warriors." William First Nation. Madahbee said the gift would be on display in the newly-constructed hub at the Union of Anishinabek and other First Nations negotiators succeeded in secur- Ontario Indians offices on Nipissing First Nation. -

2020 Msoa Architecture Program Report (APR)

McEwen School of Architecture Laurentian University Architecture Program Report for Initial Accreditation Submitted: September 15, 2020 MSoA Revised: December 3, 2020 Acknowledgments The McEwen School of Architecture acknowledges the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850 and recognizes that our School in Downtown Sudbury and the Laurentian University campus are located on the traditional lands of the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek. The City of Greater Sudbury also includes the traditional lands of Wahnapitae First Nation. We are truly honoured to have been able to work with so many inspiring Indigenous communities, partners, and colleagues throughout Northeastern Ontario since the School opened in 2013. Miigwech. This report has been compiled from a collective effort over many years, by a committed group of faculty, staff, students, university administrators and colleagues, as well as community members, who have played pivotal roles in the founding of not only a new school of architecture, but one that challenges the way we think about architectural education in relation to our Northern Ontario context. Many people from the School and the University have contributed to this report. I would like to offer special gratitude to our Administrative Assistants, Victoria Dominico and Tina Cyr, for devoting their time to this effort. Our Founding Director, Dr. Terrance Galvin, has provided invaluable guidance and devoted significant energy into the accreditation process since the School’s inception, and this report is no exception. Dr. David T Fortin, Director McEwen School of Architecture (MSoA) Laurentian University (LU) Architecture Program Report for Initial Accreditation Submitted to the Canadian Architectural Certification Board (CACB) Dr. David T. Fortin Director & Associate Professor Dr. -

A University for Timmins?

Research Paper No. 26| November 2017 A University for Timmins? Possibilities and Realities By Ken Coates northernpolicy.ca Who We Are Some of the key players in this model, and their roles, President & CEO are as follows: Charles Cirtwill Board: The Board of Directors sets strategic direction for Northern Policy Institute. Directors serve on operational committees dealing with finance, fundraising and Board of Directors governance, and collectively the Board holds the Martin Bayer (Chair) Dr. George C. Macey CEO accountable for achieving our Strategic Plan Thérèse Bergeron- (Vice-Chair & Secretary) goals. The Board’s principal responsibility is to protect Hopson (Vice Chair) Emilio Rigato (Treasurer) and promote the interests, reputation, and stature of Michael Atkins Hal J. McGonigal Northern Policy Institute. Pierre Bélanger Dawn Madahbee Leach Terry Bursey Gerry Munt President & CEO: Recommends strategic direction, Dr. Harley d’Entremont Dr. Brian Tucker develops plans and processes, and secures and Alex Freedman Diana Fuller Henninger allocates resources to achieve it. Advisory Council: A group of committed individuals interested in supporting, but not directing, the work of Northern Policy Institute. Leaders in their fields, they Advisory Council provide advice on potential researchers or points of Kim-Jo Bliss contact in the wider community. Allyson Pele Don Drummond Ogiima Due Peltier John Fior Research Advisory Board: A group of academic Peter Politis Ronald Garbutt researchers who provide guidance and input on Tina Sartoretto Audrey Gilbeau potential research directions, potential authors, Bill Spinney JP Gladu and draft studies and commentaries. They are David Thompson Peter Goring Northern Policy Institute’s formal link to the academic Frank Kallonen community. -

PRESS RELEASE for Immediate Release – June 7, 2021 Statement on Residential School Discovery the Association of Catholic Colle

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release – June 7, 2021 Statement on Residential School Discovery The Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities in Canada (ACCUC) is saddened and appalled to learn of the terrible discovery of 215 children's bodies at the former Kamloops Residential School. We are deeply disturbed by the role our church has played in this case and in the residential schools in general, and we understand that this discovery is likely only the first of more to come. To the entire Tk'emlups te Secwépemc First Nation and to the Indigenous community of Canada, we offer our deepest condolences and prayers. As the leaders of Canada’s Catholic universities and colleges, we feel it is imperative that the suffering and loss of life experienced at the residential schools are never forgotten. As centres of learning, we re-commit our institutions to the importance of Indigenous education, and to listening and working with our Indigenous communities towards the goals of conscientization, reconciliation and healing. To these ends, we also request that the complete records of the residential schools be preserved and made available to all those who seek to learn from this horrific chapter in history. Most urgently and with a filial heart, we join other Canadian Catholic organizations in urging the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops to request Pope Francis formally apologize to the survivors, their families, and to all of the Indigenous communities of Canada. We believe that the Holy Father’s apology will be important for addressing the Church’s reprehensible involvement in the federal residential school system, as well as serving as a critical start for the process of healing the multiple wounds of our Indigenous brothers and sisters. -

Ed 036 264 Institution Pub Date Edes Price

ECCUMENT RESUME ED 036 264 HE 001 314 TITLE CAMPUS AND FORUM; THIRD ANNUAL REVIEW, 1968-69. INSTITUTION COMMITTEE CF PRESIDENTS OF UNIVERSITIES OF ONTARIC, TORONTO. PUB DATE 69 NOTE 78P. EDES PRICE EDES PRICE MF-$0.50 HC-$4.00 DiSCRIPTORS *CCOPEEATIVE PLANNING, *COOPERATIVE PROGRAMS, *FINANCIAL SUPPORT, FOREIGN STUDENTS, *HIGHER EDUCATION, *INTERINSTITUTIONAL COOPERATION, STATE AID IDENTIFIERS *CANADA, ONTARIC ABSTRACT THE CREATICN OF THE COMMITTEE OF PRESIDENTS IN 1962 WAS A SIGNIFICANT STEP TOWARD SYSTEMATIC COOPERATION AMONG ONTARIO UNIVERSITIES. THIS CCCPEEATION, WHICH HAS CONSISTENTLY INCREASED, WAS THE RESPONSE TO GROWING DEPENDENCE ON PUBLIC FUNDS, AND TO INCREASED GOVERNMENT INTEREST IN HOW FUNDS WERE SPENT. THE UNIVERSITIES HAVE COOPERATED IN ESTABLISHING GRADUATE PROGRAMS, AN INTERLIBRARY LOAN SERVICE, COMMCN APPLICATION FORMS FOR ADMISSION, ENROLLMENT PROJECTIONS, AND OTHER PROJECTS. THE OPERATING GRANTS FORMULA, INTRODUCED IN 1967, HAS BEEN MCSI SUCCESSFUL. UNDER THIS FORMULA, EACH CATEGORY OF STUDENTS IS WEIGHTED AND EACH UNIVERSITY'S WEIGHTED ENROLLMENT AS CF DECEMBER 1IS MULTIPLIED BY THE VALUE OF A "BASIC INCOME UNIT." EMERGING UNIVERSITIES GET A SUPPLEMENT FOR A STATED NUMBER CF YEARS. OTHER ISSUES THAT HAVE BEEN CONSIDERED ARE THE NUMBER OF FOREIGN STUDENTS AND FACULTY AT CANADIAN INSTITUTIONS, THE RCLE OF FACULTY AND STUDENTS IN DECISION MAKING, STUDENT AID PROGRAMS, PROVISION Of STUDENT RESIDENCES AND STUDENT UNREST. APPENDICES CCNTAIN DATA ON THE MEMBERS, SUBCOMMITTEES AND EXPENDITURES CI THE COMMITTEE, A BRIEF ON RELATIONS BETWEEN UNIVERSITIES AND GOVERNMENTS, AND A PROPOSAL FOR ESTABLISHING A COUNCIL OF UNIVERSITIES OF CNTARIO. (AF) Committee of Presidents ofUniversities of Ontario Comite des Presidents d'Universitede ('Ontario CAMPUS ANDFORUM Third AnnualReview, 1968-69 U.S.