Italian Sound Italian Sounds, Lost and Found: Introduction to Volume 4, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Classical Repertoire : the Unbridgeable Gulf Between Contemporary Practice and Historical Reality

Performing Classical repertoire : the unbridgeable gulf between contemporary practice and historical reality Autor(en): Brown, Clive Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis : eine Veröffentlichung der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, Lehr- und Forschungsinstitut für Alte Musik an der Musik-Akademie der Stadt Basel Band (Jahr): 30 (2006) Heft [1] PDF erstellt am: 23.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-868963 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch 31 PERFORMING CLASSICAL REPERTOIRE: THE UNBRIDGEABLE GULF BETWEEN CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE AND HISTORICAL REALITY by Clive Brown In 1990 I was amused to see a CD of masses by Mozart, performed with period instruments, displayed in the window of Blackwell's Music Shop in Oxford with the slogan: „Mozart as he would have heard it". -

The Profane Choral Compositions of Lorenzo Perosi

THE PROFANE CHORAL COMPOSITIONS OF LORENZO PEROSI By KEVIN TODD PADWORSKI B.A., Eastern University, 2008 M.M., University of Denver, 2013 A TMUS Project submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment Of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts College of Music 2019 1 THE PROFANE CHORAL COMPOSITIONS OF LORENZO PEROSI By KEVIN TODD PADWORSKI Approved APRIL 8, 2019 ___________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Swanson Associate Director of Choral Studies and Assistant Professor of Music __________________________________________ Dr. Yonatan Malin Associate Professor of Music Theory __________________________________________ Dr. Steven Bruns Associate Dean for Graduate Studies; Associate Professor of Music Theory 2 Table of Contents Title Page Committee Approvals 1 Table of Contents 2 Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Biography 6 Profane Choral Compositions 23 Conclusion 32 Appendices 33 Appendix I: Complete List of the Profane Compositions Appendix II: Poetic Texts of Selected Profane Compositions Bibliography 36 3 Abstract The vocal music created in Italy during the late 1800s and early 1900s is often considered to be the height of European vocal art forms, and the era when the operatic and choral genres broke their way into mainstream appreciation. One specific composer’s career was paramount to the rise of this movement: Monsignor Don Lorenzo Perosi. At the turn of the twentieth century, his early premieres of choral oratorios and symphonic poems of massive scale thoroughly impressed notable musical colleagues worldwide and quickly received mass adoration and accolades. In addition to these large works, Perosi produced a prolific number of liturgical choral compositions that shaped the sound and style of choral music of the Roman Catholic Church for over half a century. -

Immigrant Musicians on the New York Jazz Scene by Ofer Gazit A

Sounds Like Home: Immigrant Musicians on the New York Jazz Scene By Ofer Gazit A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Benjamin Brinner, Chair Professor Jocelyne Guilbault Professor George Lewis Professor Scott Saul Summer 2016 Abstract Sounds Like Home: Immigrant Musicians On the New York Jazz Scene By Ofer Gazit Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Benjamin Brinner, Chair At a time of mass migration and growing xenophobia, what can we learn about the reception, incorporation, and alienation of immigrants in American society from listening to the ways they perform jazz, the ‘national music’ of their new host country? Ethnographies of contemporary migrations emphasize the palpable presence of national borders and social boundaries in the everyday life of immigrants. Ethnomusicological literature on migrant and border musics has focused primarily on the role of music in evoking a sense of home and expressing group identity and solidarity in the face of assimilation. In jazz scholarship, the articulation and crossing of genre boundaries has been tied to jazz as a symbol of national cultural identity, both in the U.S and in jazz scenes around the world. While these works cover important aspects of the relationship between nationalism, immigration and music, the role of jazz in facilitating the crossing of national borders and blurring social boundaries between immigrant and native-born musicians in the U.S. has received relatively little attention to date. -

Towards a Cultural History of Italian Oratorio Around 1700: Circulations, Contexts, and Comparisons

This is a working paper with minimal footnotes that was not written towards publication—at least not in its present form. Rather, it aims to provide some of the wider historiographical and methodological background for the specific (book) project I am working on at the Italian Academy. Please do not circulate this paper further or quote it without prior written consent. Huub van der Linden, 1 November 2013. Towards a cultural history of Italian oratorio around 1700: Circulations, contexts, and comparisons Huub van der Linden “Parlare e scrivere di musica implica sempre una storia degli ascolti possibili.” Luciano Berio, Intervista sulla musica (1981) 1. Oratorio around 1700: Historiographical issues since 1900 In the years around 1900, one Italian composer was hailed both in Italy and abroad as the future of Italian sacred music. Nowadays almost no one has heard of him. It was Don Lorenzo Perosi (1872-1956), the director of the Sistine Chapel. He was widely seen as one of the most promising new composers in Italy, to such a degree that the Italian press spoke of il momento perosiano (“the Perosian moment”) and that his oratorios appeared to usher in a new flourishing of the genre.1 His oratorios were performed all over Europe as well as in the USA, and received wide-spread attention in the press and music magazines. They also gave rise to the modern historiography of the genre. Like all historiography, that of Italian oratorio is shaped by its own historical context, and like all writing about music, it is related also to music making. -

Eighteenth-Century Reception of Italian Opera in London

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2013 Eighteenth-century reception of Italian opera in London. Kaylyn Kinder University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Kinder, Kaylyn, "Eighteenth-century reception of Italian opera in London." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 753. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/753 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY RECEPTION OF ITALIAN OPERA IN LONDON By Kaylyn Kinder B.M., Southeast Missouri State University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Division of Music History of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Department of Music University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2013 EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY RECEPTION OF ITALIAN OPERA IN LONDON By Kaylyn Kinder B.M., Southeast Missouri State University, 2009 A Thesis Approved on July 18, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Jack Ashworth, Thesis Director Douglas Shadle Daniel Weeks ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jack Ashworth, for his guidance and patience over the past two years. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. -

Programma Presentazione Del Libro “Moreschi

L’Associazione presentano il Festival Moreschi 2009 “In coro per l’Angelo di Roma” il Comune di Monte Compatri Coro Alessandro Moreschi Direttore Alessandro Vicari Coro di Voci Bianche dell’Arcum Direttore Paolo Lucci Nicholas Clapton, sopranista Orchestra d’archi dell’Associazione Moreschi Presenta Silvia Coletti 24 Maggio 2009 ore 19.00 a Monte Compatri presso il Duomo dell’Assunta in cielo Programma Presentazione del libro “Moreschi. L’Angelo di Roma” di Nicholas Clapton Traduzione: Giuliana Gentili - Edizioni Controluce Con la partecipazione: dell’autore, Nichola Clapton; del Presidente, Claudina Robbiati; della Traduttrice, Giuliana Gentili, dell’editore, Armando Guidoni; del Sindaco di Monte Compatri, Marco De Carolis Concerto del controtenore Nicholas Clapton George Friderich Handel (1685-1759) Where'er you walk (dal "Semele") George Friderich Handel (1685-1759) Verdi prati (dal "Alcina") George Friderich Handel (1685-1759) Stille amare (dal "Tolomeo") Christoph von Gluck (1714-1787) Che farò senza Euridice? (da "Orfeo ed Eurdice") Con l’Orchestra d’archi dell’Associazione Moreschi Direttore: Alessandro Vicari Concerto del Coro di Voci Bianche dell’Arcum Anonimo Sec. XIII Alleluja, alto re di gloria (elab. Paolo Lucci) Giovanni Animuccia(ca 1514-1571) Laudate Dio (trascr. Lavinio Virgili) Giovanni P.gi da Palestrina (1525-1594) Jesu! Rex admirabilis Felice Anerio (1560-1614) O Jesu mi dolcissimo Anonimo Tu del Libano il candore (elab. A.do Boreggi) Anonimo O Madre, tu dai cieli (elab. Arnaldo Boreggi) Lorenzo Perosi (1872-1956) Signor che in ciel (trascr. Arnaldo Boreggi) Giulio Cesare Paribeni (1881-1964) Gesù in sogno Bonaventura Somma (1893-1960) Campane a sera Nino Rota (1911-1979) Ovunque il guardo io giro Paolo Lucci (1948) Nil nostri miserere? George Friedrich Haendel (1685-1759) Joy to the world (trascr. -

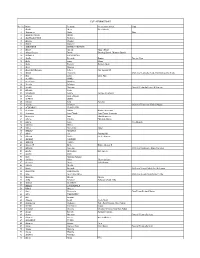

Nr. Crt Nume Prenume Pseudonim Artistic Grup 1 Abaribi Diego Diego Abaribi 2 Abatangelo Giulio Klune 3 ABATANTUONO DIEGO 4 ABATE

LISTA MEMBRI UNART Nr. Crt Nume Prenume Pseudonim Artistic Grup 1 Abaribi Diego Diego Abaribi 2 Abatangelo Giulio Klune 3 ABATANTUONO DIEGO 4 ABATEGIOVANNI FRANCA 5 Abbado Claudio 6 Abbiati Giovanni 7 ABBONDATI MANOLO CRISTIAN 8 Abbott Vincent Vinnie Abbott 9 Abbott (Estate) Darrell Dimebag Darrell, Diamond Darrell 10 ABDALLA SAID CAROLA 11 Abeille Riccardo Ronnie Dancing Crap 12 Abela Laura L'Aura 13 Abels Zachary Zachary Abels 14 Abeni Maurizio 15 Abossolo Mbossoro Fabien Sisi / Logobit Gt 16 Abriani Emanuela Orchestra Teatro alla Scala, Filarmonica della Scala 17 Abur Ioana Ioana Abur 18 ACAMPA MARIO 19 Accademia Bizantina 20 Accardo Salvatore 21 Accolla Giuseppe Coro del Teatro La Fenice di Venezia 22 Achenza Paolo 23 Achermann Jerome Jerome Achermann 24 Achiaua Andrei-Marian 25 ACHILLI GIULIA 26 Achoun Sofia Samaha 27 Acierno Salvatore Orchestra Teatro San Carlo di Napoli 28 ACQUAROLI FRANCESCO 29 Acquaviva Battista Battista Acquaviva, 30 Acquaviva Jean-Claude Jean-Claude Acquaviva 31 Acquaviva John John Acquaviva 32 Adamo Cristian Christian Adamo 33 Adamo Ivano New Disorder 34 Addabbo Matteo 35 Addea Alessandro Addal 36 ADEZIO GIULIANA 37 Adiele Eric Sporting Life 38 Adisson Gaelle Gaelle Adisson 39 ADORNI LORENZO 40 ADRIANI LAURA 41 Afanasieff Walter Walter Afanasieff 42 Affilastro Giuseppe Orchestra Fondazione Arturo Toscanini 43 Agache Alexandrina Dida Agache 44 Agache Iulian 45 Agate Girolamo Antonio 46 Agebjorn Johan Johan Agebjorn 47 Agebjorn Hanna Sally Shapiro 48 Agliardi Niccolò 49 Agosti Riccardo Orchestra Teatro Carlo -

Italian-Australian Musicians, ‘Argentino’ Tango Bands and the Australian Tango Band Era

2011 © John Whiteoak, Context 35/36 (2010/2011): 93–110. Italian-Australian Musicians, ‘Argentino’ Tango Bands and the Australian Tango Band Era John Whiteoak For more than two decades from the commencement of Italian mass migration to Australia post-World War II, Italian-Australian affinity with Hispanic music was dynamically expressed through the immense popularity of Latin-American inflected dance music within the Italian communities, and the formation of numerous ‘Italian-Latin’ bands with names like Duo Moreno, El Bajon, El Combo Tropicale, Estrellita, Mambo, Los Amigos, Los Muchachos, Mokambo, Sombrero, Tequila and so forth. For venue proprietors wanting to offer live ‘Latin- American’ music, the obvious choice was to hire an Italian band. Even today, if one attends an Italian community gala night or club dinner-dance, the first or second dance number is likely to be a cha-cha-cha, mambo, tango, or else a Latinised Italian hit song played and sung in a way that is unmistakably Italian-Latin—to a packed dance floor. This article is the fifteenth in a series of publications relating to a major monograph project, The Tango Touch: ‘Latin’ and ‘Continental’ Influences on Music and Dance before Australian ‘Multiculturalism.’1 The present article explains how the Italian affinity for Hispanic music was first manifested in Australian popular culture in the form of Italian-led ‘Argentino tango,’ ‘gaucho-tango,’ ‘Gypsy-tango,’ ‘rumba,’ ‘cosmopolitan’ or ‘all-nations’ bands, and through individual talented and entrepreneurial Italian-Australians who were noted for their expertise in Hispanic and related musics. It describes how a real or perceived Italian affinity with Hispanic and other so-called ‘tango band music’ opened a gateway to professional opportunity for various Italian-Australians, piano accordionists in particular. -

EJ Full Draft**

Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy By Edward Lee Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfacation of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair Professor James Q. Davies Professor Ian Duncan Professor Nicholas Mathew Summer 2020 Abstract Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy by Edward Lee Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair This dissertation emerged out of an archival study of Italian opera libretti published between 1800 and 1835. Many of these libretti, in contrast to their eighteenth- century counterparts, contain lengthy historical introductions, extended scenic descriptions, anthropological footnotes, and even bibliographies, all of which suggest that many operas depended on the absorption of a printed text to inflect or supplement the spectacle onstage. This dissertation thus explores how literature— and, specifically, the act of reading—shaped the composition and early reception of works by Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and their contemporaries. Rather than offering a straightforward comparative study between literary and musical texts, the various chapters track the often elusive ways that literature and music commingle in the consumption of opera by exploring a series of modes through which Italians engaged with their national past. In doing so, the dissertation follows recent, anthropologically inspired studies that have focused on spectatorship, embodiment, and attention. But while these chapters attempt to reconstruct the perceptive filters that educated classes would have brought to the opera, they also reject the historicist fantasy that spectator experience can ever be recovered, arguing instead that great rewards can be found in a sympathetic hearing of music as it appears to us today. -

“Notes on Sprezzatura: Current Influences on Italian Jazz.” Irene

“Notes on Sprezzatura: Current Influences on Italian Jazz.” Irene Monteverde, December 2015 Abstract: Italians have a certain “Sprezzatura” when it comes to art, and jazz in particular - “an effortlessness mastery, a discreet modesty, accomplishment mixed with unaffectedness.” This paper examines the accomplishments of some of today’s top Italian jazz musicians and uses some personal accounts to try to extrapolate the exact recipe for the “Sprezzatura” in jazz. Stefano Battaglia, Franco Santarnecchi, Enrico Rava, and Alessio Riccio are just a few Italian jazz musicians that embody the “effortless, unaffected modesty,” whether on stage, in a classroom or during an interview. At the same time, Italians maintain a hallowed respect for the American-born tradition; Enrico Rava recently performed an entire concert of arranged Michael Jackson songs, while Stefano Battaglia produced a CD of Alec Wilder compositions. Italy is a country dividend geographically, socially, ideologically, and familially, a factor that seems to drives groups to carry-out business underground. It may be an attitude long-ingrained in Italian culture, but could this be why the jazz scene seems to thrive in underground circles? Could the “discreetness” be attributed to a country divided? According to Francesco Martinelli, jazz writer and festival coordinator, “Italian government has little influence on Italian life.” If anything, the government makes it harder for good music to shine through to the public. Independent jazz schools struggle to stay afloat while unqualified -

Mazzini's Filosofia Della Musica: an Early Nineteenth-Century Vision Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture MAZZINI’S FILOSOFIA DELLA MUSICA: AN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY VISION OF OPERATIC REFORM A Thesis in Musicology by Claire Thompson © 2012 Claire Thompson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2012 ii The thesis of Claire Thompson was reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles Youmans Associate Professor of Musicology Thesis Adviser Marie Sumner Lott Assistant Professor of Musicology Sue Haug Director of the School of Music *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT Although he is better known for his political writings and for heading a series of failed revolutions in mid-nineteenth century Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini also delved into the realm of music aesthetics with his treatise Filosofia della Musica. Ignoring technical considerations, Mazzini concerned himself with the broader social implications of opera, calling for operatic reform to combat Italian opera’s materialism, its lack of unifying characteristics, and its privileging of melody over all other considerations. Mazzini frames his argument for the transformation of opera into a social art within the context of a larger Hegelian dialectic, which pits Italian music (which Mazzini associates with melody and the individual) against German music (which Mazzini associates with harmony and society). The resulting synthesis, according to Mazzini, would be a moral operatic drama, situating individuals within a greater society, and manifesting itself in a cosmopolitan or pan-European style of music. This thesis explores Mazzini’s treatise, including the context of its creation, the biases it demonstrates, the philosophical issues it raises about the nature and role of music, and the individual details of Mazzini’s vision of reform. -

Note by Martin Pearlman the Castrato Voice One of The

Note by Martin Pearlman © Martin Pearlman, 2020 The castrato voice One of the great gaps in our knowledge of "original instruments" is in our lack of experience with the castrato voice, a voice type that was at one time enormously popular in opera and religious music but that completely disappeared over a century ago. The first European accounts of the castrato voice, the high male soprano or contralto, come from the mid-sixteenth century, when it was heard in the Sistine Chapel and other church choirs where, due to the biblical injunction, "let women remain silent in church" (I Corinthians), only men were allowed to sing. But castrati quickly moved beyond the church. Already by the beginning of the seventeenth century, they were frequently assigned male and female roles in the earliest operas, most famously perhaps in Monteverdi's L'Orfeo and L'incoronazione di Poppea. By the end of that century, castrati had become popular stars of opera, taking the kinds of leading heroic roles that were later assigned to the modern tenor voice. Impresarios like Handel were able to keep their companies afloat with the star power of names like Farinelli, Senesino and Guadagni, despite their extremely high fees, and composers such as Mozart and Gluck (in the original version of Orfeo) wrote for them. The most successful castrati were highly esteemed throughout most of Europe, even though the practice of castrating young boys was officially forbidden. The eighteenth-century historian Charles Burney described being sent from one Italian city to another to find places where the operations were performed, but everyone claimed that it was done somewhere else: "The operation most certainly is against law in all these places, as well as against nature; and all the Italians are so much ashamed of it, that in every province they transfer it to some other." By the end of the eighteenth century, the popularity of the castrato voice was on the decline throughout Europe because of moral and humanitarian objections, as well as changes in musical tastes.