The Mythological Role of the Hymen in Virginity Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

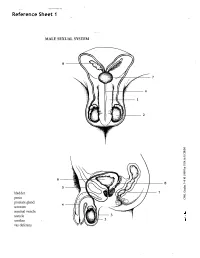

Reference Sheet 1

MALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 8 7 8 OJ 7 .£l"00\.....• ;:; ::>0\~ <Il '"~IQ)I"->. ~cru::>s ~ 6 5 bladder penis prostate gland 4 scrotum seminal vesicle testicle urethra vas deferens FEMALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 2 1 8 " \ 5 ... - ... j 4 labia \ ""\ bladderFallopian"k. "'"f"";".'''¥'&.tube\'WIT / I cervixt r r' \ \ clitorisurethrauterus 7 \ ~~ ;~f4f~ ~:iJ 3 ovaryvagina / ~ 2 / \ \\"- 9 6 adapted from F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System Reference Sheet 3: GLOSSARY Anus – The opening in the buttocks from which bowel movements come when a person goes to the bathroom. It is part of the digestive system; it gets rid of body wastes. Buttocks – The medical word for a person’s “bottom” or “rear end.” Cervix – The opening of the uterus into the vagina. Circumcision – An operation to remove the foreskin from the penis. Cowper’s Glands – Glands on either side of the urethra that make a discharge which lines the urethra when a man gets an erection, making it less acid-like to protect the sperm. Clitoris – The part of the female genitals that’s full of nerves and becomes erect. It has a glans and a shaft like the penis, but only its glans is on the out side of the body, and it’s much smaller. Discharge – Liquid. Urine and semen are kinds of discharge, but the word is usually used to describe either the normal wetness of the vagina or the abnormal wetness that may come from an infection in the penis or vagina. Duct – Tube, the fallopian tubes may be called oviducts, because they are the path for an ovum. -

Age and Sexual Consent

Per Se or Power? Age and Sexual Consent Joseph J. Fischel* ABSTRACT: Legal theorists, liberal philosophers, and feminist scholars have written extensively on questions surrounding consent and sexual consent, with particular attention paid to the sorts of conditions that validate or vitiate consent, and to whether or not consent is an adequate metric to determine ethical and legal conduct. So too, many have written on the historical construction of childhood, and how this concept has influenced contemporary legal culture and more broadly informed civil society and its social divisions. Far less has been written, however, on a potent point of contact between these two fields: age of consent laws governing sexual activity. Partially on account of this under-theorization, such statutes are often taken for granted as reflecting rather than creating distinctions between adults and youth, between consensual competency and incapacity, and between the time for innocence and the time for sex. In this Article, I argue for relatively modest reforms to contemporary age of consent statutes but propose a theoretic reconstruction of the principles that inform them. After briefly historicizing age of consent statutes in the United States (Part I), I assert that the concept of sexual autonomy ought to govern legal regulations concerning age, age difference, and sexual activity (Part II). A commitment to sexual autonomy portends a lowered age of sexual consent, decriminalization of sex between minors, heightened legal supervision focusing on age difference and relations of dependence, more robust standards of consent for sex between minors and between minors and adults, and greater attention to the ways concerns about age, age difference, and sex both reflect and displace more normatively apt questions around gender, gendered power and submission, and queer sexuality (Part III). -

'Virginity Is a Virtue: Prevent Early Sex': Teacher Perceptions of Sex

`Virginity is a virtue: prevent early sex': teacher perceptions of sex education in a Ugandan secondary school Article (Accepted Version) Iyer, Padmini and Aggleton, Peter (2014) ‘Virginity is a virtue: prevent early sex’: teacher perceptions of sex education in a Ugandan secondary school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 35 (3). pp. 432-448. ISSN 0142-5692 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/55733/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk British Journal of Sociology of Education, 2014 Vol. -

Preparation for Your Sex Life

1 Preparation for Your Sex Life Will every woman bleed during her first sexual intercourse? • Absolutely not. Not every woman has obvious bleeding after her first sexual intercourse. • Bleeding is due to hymen breaking during penetration of the penis into the vagina. We usually refer it as "spotting". It is normal and generally resolves. • Some girls may not have hymen at birth, or the hymen may have been broken already when engaging in vigorous sports. Therefore, there may be no bleeding. Is it true that all women will experience intolerable pain during their first sexual intercourse? • It varies among individuals. Only a small proportion of women report intolerable pain during their first sexual intercourse. The remaining report mild pain, tolerable pain or painless feeling. • Applying lubricants to genitals may relieve the discomfort associated with sexual intercourse; however, if you experience intolerable pain or have heavy or persistent bleeding during or after sexual intercourse, please seek medical advice promptly. How to avoid having menses during honeymoon? • To prepare in advance, taking hormonal pills like oral contraceptive pills or progestogens under doctor's guidance can control menstrual cycle and thereby avoid having menses during honeymoon. Is it true that women will get Honeymoon Cystitis easily during honeymoon? • During sexual intercourse, bacteria around perineum and anus may move upward to the bladder causing cystitis. Symptoms include frequent urination, difficulty and pain when urinating. • There may be more frequent sexual activity during honeymoon period, and so is the chance of having cystitis. The condition is therefore known as "honeymoon cystitis". • Preventive measures include perineal hygiene, drinking plenty of water, empty your bladder after sexual intercourse and avoid the habit of withholding urine. -

Representations of Virginity in the Media

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons Gender & Sexuality Studies Student Work Collection School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences 2020 Representations of Virginity in the Media DAKOTA MURRAY [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/gender_studies Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation MURRAY, DAKOTA, "Representations of Virginity in the Media" (2020). Gender & Sexuality Studies Student Work Collection. 52. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/gender_studies/52 This Undergraduate Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gender & Sexuality Studies Student Work Collection by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. REPRESENTATIONS OF VIRGINITY IN T H E M E D I A D A KO TA MURRAY TSOC 455 VIRGINITY - WHAT IS IT? CONVENTIONAL DEFINITION: SOMEONE WHO HASN’T HAD SEX IN REALITY, VIRGINITY IS A sex means different things to COMPLEXTERM TO DEFINE different people, so virginity can mean different things too NEWSFLASH! The state of your ❖ Some believe sex requires penetration hymen does NOT ❖ Many LGBTQ+ will never have control your penis-in-vagina sex virginity* ❖ Others believe that oral sex counts ❖ Many believe that non-consensual sex does not count *All hymens are not created equal. So many things other than intercourse can wear the hymen away, including horseback riding, biking, gymnastics, using tampons, fingering, and masturbation, which basically leads to "breaking" the hymen without ever having sex. Some women are even born without hymens. -

MR Imaging of Vaginal Morphology, Paravaginal Attachments and Ligaments

MR imaging of vaginal morph:ingynious 05/06/15 10:09 Pagina 53 Original article MR imaging of vaginal morphology, paravaginal attachments and ligaments. Normal features VITTORIO PILONI Iniziativa Medica, Diagnostic Imaging Centre, Monselice (Padova), Italy Abstract: Aim: To define the MR appearance of the intact vaginal and paravaginal anatomy. Method: the pelvic MR examinations achieved with external coil of 25 nulliparous women (group A), mean age 31.3 range 28-35 years without pelvic floor dysfunctions, were compared with those of 8 women who had cesarean delivery (group B), mean age 34.1 range 31-40 years, for evidence of (a) vaginal morphology, length and axis inclination; (b) perineal body’s position with respect to the hymen plane; and (c) visibility of paravaginal attachments and lig- aments. Results: in both groups, axial MR images showed that the upper vagina had an horizontal, linear shape in over 91%; the middle vagi- na an H-shape or W-shape in 74% and 26%, respectively; and the lower vagina a U-shape in 82% of cases. Vaginal length, axis inclination and distance of perineal body to the hymen were not significantly different between the two groups (mean ± SD 77.3 ± 3.2 mm vs 74.3 ± 5.2 mm; 70.1 ± 4.8 degrees vs 74.04 ± 1.6 degrees; and +3.2 ± 2.4 mm vs + 2.4 ± 1.8 mm, in group A and B, respectively, P > 0.05). Overall, the lower third vaginal morphology was the less easily identifiable structure (visibility score, 2); the uterosacral ligaments and the parau- rethral ligaments were the most frequently depicted attachments (visibility score, 3 and 4, respectively); the distance of the perineal body to the hymen was the most consistent reference landmark (mean +3 mm, range -2 to + 5 mm, visibility score 4). -

Evaluation of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Evaluation of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Christine M. Corbin, MD Northwest Gynecology Associates, LLC April 26, 2011 Outline l Review of normal menstrual cycle physiology l Review of normal uterine anatomy l Pathophysiology l Evaluation/Work-up l Treatment Options - Tried and true-not so new - Technology era options Menstrual cycle l Menstruation l Proliferative phase -- Follicular phase l Ovulation l Secretory phase -- Luteal phase l Menstruation....again! Menstruation l Eumenorrhea- normal, predictable menstruation - Typically 2-7 days in length - Approximately 35 ml (range 10-80 ml WNL - Gradually increasing estrogen in early follicular phase slows flow - Remember...first day of bleeding = first day of “cycle” Proliferative Phase/Follicular Phase l Gradual increase of estrogen from developing follicle l Uterine lining “proliferates” in response l Increasing levels of FSH from anterior pituitary l Follicles stimulated and compete for dominance l “Dominant follicle” reaches maturity l Estradiol increased due to follicle formation l Estradiol initially suppresses production of LH Proliferative Phase/Follicular Phase l Length of follicular phase varies from woman to woman l Often shorter in perimenopausal women which leads to shorter intervals between periods l Increasing estrogen causes alteration in cervical mucus l Mature follicle is approximately 2 cm on ultrasound measurement just prior to ovulation Ovulation l Increasing estradiol surpasses threshold and stimulates release of LH from anterior pituitary l Two different receptors for -

Hymen Variations

Hymen Variations What is the hymen? The hymen is a thin piece of tissue located at the opening of the vagina. Hymens come in different shapes, the most common shapes are crescent or annular (circular). The hymen needs to be open to allow menstrual blood and normal secretions to pass through the vagina. Anatomic variations of the normal hymen. (A) normal, What is an imperforate hymen? (B) imperforate, (C) microperforate, (D) cribiform, and If there is an imperforate hymen, the hymen tissue (E) septate. completely covers the vaginal opening. This prevents Reprinted with permission from Laufer MR. Office Evaluation of the Child and menstrual blood and normal secretions from exiting the Adolescent. In Emans SJ, Laufer MR, editors. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 6th ed. Philadelphia [PA]: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & vagina. Wilkins; 2012. P. 5 An imperforate hymen may be diagnosed at birth, but more commonly, it is found during puberty. If noted at birth and it is not causing any issues with urination, the How are hymen variations treated? imperforate hymen can be managed after puberty Treatment of extra hymen tissue (imperforate, begins. When the hymen is imperforate, the vagina microperforate, septate, or cribiform hymens) is a becomes filled with a large amount of blood, which may minor outpatient procedure, called a“ hymenectomy” – cause pain or difficulty urinating. during which the excess tissue is removed. The hymen tissue does not grow back. Once it is removed, the vaginal opening is an adequate size for What are other hymen variations? the flow of menstrual blood and normal vaginal secretions, tampon use, and vaginal intercourse. -

Virginity- an Update on Uncharted Territory Mehak Nagpal1 and T

em & yst Se S xu e a v l i t D c i Reproductive System & Sexual s u o Nagpal and Rao, Reprod Syst Sex Disord 2016, 5:2 d r o d r e p r e DOI: 10.4172/2161-038X.1000178 s R Disorders: Current Research ISSN: 2161-038X Review Article Open Access Virginity- An Update on Uncharted Territory Mehak Nagpal1 and T. S. Sathyanarayana Rao2* 1Department of Psychiatry, E.S.I.C Model Hospital & PGIMSR, New Delhi, India 2Department of Psychiatry, JSS Medical College Hospital, JSS University, Mysuru, India *Corresponding author: Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Department of Psychiatry, JSS Medical College Hospital, JSS University, Mysuru, India, Tel: 0821-254-8400; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: June 4, 2016; Acc date: June 23, 2016; Pub date: June 29, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Nagpal M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Traditionally cultures around the world place a high value on virginity in women leading to tremendous pressure on girls and their families. Today it continues to play the role of a major determinant in their future sexual lives. Historically and socially it is considered an exalted virtue denoting purity. However, with the recent changes in sexual freedom amongst women, it is necessary to examine certain recent issues with reference to feminine sexuality as well its bio-psycho-social roots. It is important to understand the significance of social constraints on sexuality and reproduction within the different cultural systems along with the dominant influence of religious sentiments on virginity. -

Abstinence-Only Sex Education in the United States: How Abstinence Curricula Have Harmed America

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 5-30-2017 Abstinence-only Sex Education in the United States: How Abstinence Curricula Have Harmed America Moira N. Lynch Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lynch, Moira N., "Abstinence-only Sex Education in the United States: How Abstinence Curricula Have Harmed America" (2017). University Honors Theses. Paper 380. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.372 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Abstinence-only Sex Education in the United States: How Abstinence Curricula Have Harmed America by Moira Lynch An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Community Health Education Thesis Adviser Tina Burdsall Portland State University 2015 Lynch i Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Womena Faqs: Do Menstrual Cups Affect Hymens/Virginity?

WOMENA FAQS: DO MENSTRUAL CUPS AFFECT HYMENS/VIRGINITY? WOMENA SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS1 Many people believe that - girls are born with a hymen in the form of a solid membrane covering the vaginal opening. - the hymen can be identified through physical or visual examination. - the hymen is always broken at first vaginal sexual intercourse, causing bleeding. - therefore, a lack of blood on the wedding night proves the bride is not a virgin. However, there is increasing evidence and awareness that none of these beliefs are correct. Usually there is no solid membrane covering the vagina. Instead, there is folded mucosal tissue inside the vagina. Some now call it a ‘hymenal ring/rim’ or ‘vaginal corona’. The appearance of the hymen/corona varies among individuals, and may change over time. Hormones make the corona more elastic in puberty. Daily activities (such as cycling, sports, inserting tampons or menstrual cups) may affect appearance. It is impossible to test whether a girl or woman is a virgin by inspecting her corona, either visually, or by inserting two fingers into the vagina (the ‘two-finger test’). The UN strongly recommends against these “virginity tests” as they are inaccurate, and harmful. Bleeding at first vaginal intercourse does not always happen. There are only few studies, but estimates range from around 30% to around 70%. Virginity before marriage is an important value in many religions and cultures. The definition of ‘virginity’ varies between communities and among religious leaders. Many agree that virginity is defined by first vaginal intercourse, not by bleeding. WoMena believes in providing best available evidence, so that women and girls, and their communities, can make informed choice. -

Love Without a Name: Celibates and Friendship

LOVE WITHOUT A NAME: CELIBATES AND FRIENDSHIP Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theological Studies By Sr. Eucharia P. Gomba UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio DECEMBER, 2010 LOVE WITHOUT A NAME: CELIBATES AND FRIENDSHIP APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ Jana Bennett, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Matthew Levering, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ William Roberts, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Chairperson ii ABSTRACT LOVE WITHOUT A NAME: CELIBATES AND FRIENDSHIP Name: Gomba, Sr.Eucharia P. University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Jana M. Bennett This research paper seeks to examine/investigate the role of friendship among men and women who took the vow of consecrated chastity. Despite their close connection with God, priests and nuns are human. They crave for intimacy and more often fall in love. This becomes complicated and sometimes devastating. The dual challenge faced by these celibates is to grow in communion with God and develop good relationships with people. This thesis attempts to meet that challenge by showing that human friendship enhances our understanding of friendship with God. Celibate life is not a solitary enterprise, but is what happens to us in relationship to others in friendship. Through biblical and theological reflection and a close analysis of the vow of chastity, I wish to show that it is possible to live great friendships in celibacy without the relationship being transformed into a marital romance. Chaste celibacy is a renunciation of what is beautiful in a human person for the sake of the Kingdom.