Educational Aspects of Karate: Discussing Their Representations in Filming1*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2020

January 2020 6:10 PM ET/3:10 PM PT 3:30 PM ET/12:30 PM PT 3:05 PM ET/12:05 PM PT 5:10 PM CT/4:10 PM MT 2:30 PM CT/1:30 PM MT 2:05 PM CT/1:05 PM MT The Trailer Show Three Wishes Leaves of Grass 6:50 PM ET/3:50 PM PT 5:30 PM ET/2:30 PM PT 4:55 PM ET/1:55 PM PT 5:50 PM CT/4:50 PM MT 4:30 PM CT/3:30 PM MT 3:55 PM CT/2:55 PM MT The Karate Kid Feast of Love The Burning Bed 9:00 PM ET/6:00 PM PT 7:20 PM ET/4:20 PM PT 6:45 PM ET/3:45 PM PT 8:00 PM CT/7:00 PM MT 6:20 PM CT/5:20 PM MT 5:45 PM CT/4:45 PM MT The Karate Kid: Part II Half Past Dead Rain Man WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 1 10:55 PM ET/7:55 PM PT 9:00 PM ET/6:00 PM PT 9:00 PM ET/6:00 PM PT 12:30 AM ET/9:30 PM PT 9:55 PM CT/8:55 PM MT 8:00 PM CT/7:00 PM MT 8:00 PM CT/7:00 PM MT 11:30 PM CT/10:30 PM MT Airplane II: The Sequel The Karate Kid III Convoy The Professional 10:55 PM ET/7:55 PM PT 10:55 PM ET/7:55 PM PT 2:00 AM ET/11:00 PM PT 9:55 PM CT/8:55 PM MT 9:55 PM CT/8:55 PM MT 1:00 AM CT/12:00 AM MT THURSDAY, JANUARY 2 12:50 AM ET/9:50 PM PT Assassination Primal Fear The Tuxedo 11:50 PM CT/10:50 PM MT 3:40 AM ET/12:40 AM PT 2:40 AM CT/1:40 AM MT Colors FRIDAY, JANUARY 3 SATURDAY, JANUARY 4 2:55 AM ET/11:55 PM PT 12:25 AM ET/9:25 PM PT 1:10 AM ET/10:10 PM PT Showgirls 1:55 AM CT/12:55 AM MT 11:25 PM CT/10:25 PM MT 12:10 AM CT/11:10 PM MT 6:00 AM ET/3:00 AM PT 5:00 AM CT/4:00 AM MT Assassination Half Past Dead The Professional 4:25 AM ET/1:25 AM PT 2:05 AM ET/11:05 PM PT 3:05 AM ET/12:05 AM PT The Doors: Mr. -

Hawaii's Film & Television Legacy

FilmHawaii HAWAII FILM OFFICE | State of Hawaii, Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism| 250 South Hotel St., 5th Floor | Honolulu, HI 96813 Mailing Address: P.O. Box 2359 | Honolulu, HI 96804 | Phone (808) 586-2570 | Fax (808) 586-2572 | [email protected] Hawaii’s Film & Television Legacy __________________________ More than a century of Made-in-Hawaii films and television shows. The sleek helicopter began its descent against a backdrop of breathtaking tropical mountains and rain forests, finally hovering in the face of a plunging waterfall, then settling on the landing pad of Jurassic Park. It is a memorable live action moment from the Steven Spielberg motion picture, which widened our view of what is real and what is make believe. Spielberg’s scene was taken from Michael Crichton’s best selling novel, set on an imaginary island off the shore of the Central American nation of Costa Rica. But it was shot on the island of Kauai, in the Hawaiian archipelago. The picture grossed $920 million. Outsized creatures, of course, were not new to the movies or to Hawaii when Spielberg's velociraptors were running wild on Kauai and Oahu. Dino deLaurentis and Paramount had filmed the Jessica Lange remake of King Kong on Kauai's Na Pali Coast in 1976. In 1997, Disney remade Mighty Joe Young against the backdrop of the Kaaawa Valley, demonstrating for the umpteenth time that Hawaii does a beautiful job of standing in for Equatorial Africa. And TriStar used rural areas of Honolulu County as Tahiti, Panama, and Jamaica for a new Godzilla. -

The Karate Kid Part II 1986

A Je:rry int:raub oduction of A John G. Avildsen Film KARATE KID II Written by Robert Mark Kamen REV. SECOND DRAFT st 25, 1985 • A lie becomes truth only if you want to believe it • .•. Miyagi • KARATE KID II OPEH TO: • The CREDITS ROLLIHG over a reprise of selected scenes from Karate Kid I which will illuminate first-time viewers and remind our loyal following what's gone on before. The scenes build to the last dramatic moment of the tournament, Daniel's winning kick. Bill Conti's soaring score~ The crowd's overwhelming enthusiasm. Miyagl's satisfied, all-knowing smile. FADE OUT. FADE IH: 1 IHT. SHOWER 1 Steam and the sound of a SHOWER FILL the SCREEH. Daniel!s V~O. from the shower. DANIEL CO.S.) Hey, Mr. Miyagi, I was thinking. MIYAGI stands outside the shower holding a towel. MIYAGI About what, Daniel-san? DANIEL CO.S.) • That maybe we should have a strategy now. MIYAGI For what? DANIEL (0.S.) My tournament career. MIYAGI Miyagi already has one. The SHOWER STOPS, DANIEL's wet head pops out. DAHIEL Yeah? What is it? Miyagi hands l1im the towel. MIYAGI Permanent retirement. Miyagi turns and exits, leaving Daniel slightly bemused and dripping. • CUT TO: 2 EXT. COMPETITION HALL - DAY 2 Daniel is signing the last of a group of autographs of young, adoring fans. TTiyagi stands by his side. The • REFEREE and the ANNOUNCER come walking over. REFEREE Very impressive win, son~ You showed a lot of poise under pressure. DAHIEL ThanJ; you. ANNOUHCER Reople will be talking about that last kick for years. -

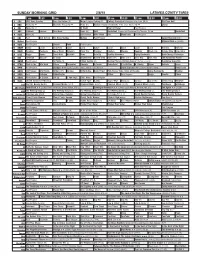

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

The Karate Kid Spider-Man 3 the Karate Kid II Monsters, Inc. The

The Karate Kid Spider-Man 3 The Karate Kid II Monsters, Inc. The Karate Kid III The Dark Knight Spider-Man The Dark Knight Rises Spider-Man 2 Star Wars Episode VI: Return of The Jedi The Karate Kid- Staring Ralph Macchio and Pat Morita. A handy man/martial arts master named Mr. Miyagi agrees to teach a bullied boy named Daniel karate and shows him that there is more to the martial art than fighting. Daniel must win a karate tournament if he wants to not be bullied any more. Return to menu The Karate Kid; part II- Mr. Miyagi and Daniel are back for more. Daniel accompanies his mentor to Okinawa Mr. Miyagi home to see his dying father and to confront his old rival, while Daniel makes an enemy of his own. Daniel finds a new love in Okinawa. Return to menu The Karate Kid; part III- The Cobra Kais dojo owner Kreese life has been tattered after Daniel and Mr. Miyagi defeat them in the karate tournament. Kreese visits his old Vietnam war buddy to give him the news. His buddy vows that he will get Kreese his revenge on them. He gets a fierce fighter to challenge Daniel in the upcoming karate tournament. Return to menu Spider-Man- Tobey Maguire as Peter Parker and Spider-Man. When bitten by a genetically modified spider, a nerdy, shy, and awkward high school student gains spider- like abilities that he will eventually use to fight evil. Return to menu Spider-Man 2 – Peter Parker is beset with troubles in his failing personal life as he battles a brilliant scientist named Doctor Otto Octavius. -

Worldradiohistory.Com › Archive-Billboard › 90S › 1990 › BB

IN THIS ISSUE # t% * ***-x*;: *3- DIGIT 908 006817973 4401 9013 MAR92QGZ PolyGram Has `Fine' MONJTY GREENLY APT A Future In U.S., Says 3740 ELM LONG BEACH CA 90807 Label's Global Chief PAGE 6 Simmons Links Rush Labels With Columbia PAGE 6 R THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT March 31, 1990/$4.50 (U.S.), $5.50 (CAN.), £3.50 (U.K.) Newest Sell -Thru Megahit Pubs, Writers On Lyric Sidelines A `Honey' In Sales, Rentals Trade Groups Won't Fight Labeling Bills vol- BY EARL PAIGE disers because it's a family movie. BY BILL HOLLAND feels the industry needs to take We also see it promising as a gift Tennessee Stickering Bill Appears untary self-regulation more serious- LOS ANGELES -The Buena Vista item." WASHINGTON, D.C. -The leading To Have Fizzled Out ... See Page 5 ly. Home Video release "Honey, I Video buyer Gail Reed at 54 -store associations of music publishers and "NMPA has no position on this as Shrunk The Kids," the last of three Spec's Music in Miami says, "Every songwriters have decided not to join ers and writers, have joined the re- yet," Murphy says. "While no one is for a moment there shouldn't closely watched early -1990 sell - piece rented." In terms of sales, the music industry fight against the cently formed Coalition Against Lyr- saying through blockbusters, jumped out though, she says the Disney comedy passage of state record-labeling bills ics Legislation. be First Amendment protection, free of the box with solid showings in is running "100 pieces" behind at this time. -

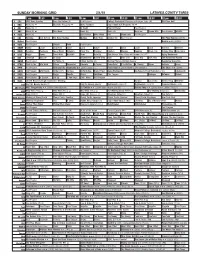

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Build a Be4er Neplix, Win a Million Dollars?

Build a Be)er Ne,lix, Win a Million Dollars? Lester Mackey 2012 USA Science and Engineering FesDval Nelix • Rents & streams movies and TV shows • 100,000 movie Dtles • 26 million customers Recommends “Movies You’ll ♥” Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ Hated it! Loved it! Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ How This Works Top Secret Now I’m Cinematch Computer Program I don’t unhappy! like this movie. Your Predicted Rang: Back at Ne,lix How can we Let’s have a improve contest! Cinematch? What should the prize be? How about $1 million? The Ne,lix Prize October 2, 2006 • Contest open to the world • 100 million movie rangs released to public • Goal: Create computer program to predict rangs • $1 Million Grand Prize for beang Cinematch accuracy by 10% • $50,000 Progress Prize for the team with the best predicDons each year 5,100 teams from 186 countries entered Dinosaur Planet David Weiss David Lin Lester Mackey Team Dinosaur Planet The Rangs • Training Set – What computer programs use to learn customer preferences – Each entry: July 5, 1999 – 100,500,000 rangs in total – 480,000 customers and 18,000 movies The Rangs: A Closer Look Highest Rated Movies The Shawshank RedempDon Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King Raiders of the Lost Ark Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers Finding Nemo The Green Mile Most Divisive Movies Fahrenheit 9/11 Napoleon Dynamite Pearl Harbor Miss Congeniality Lost in Translaon The Royal Tenenbaums How the Contest Worked • Quiz Set & Test Set – Used to evaluate accuracy of computer programs – Each entry: Rang Sept. -

Four Star Films, Box Office Hits, Indies and Imports, Movies A

Four Star Films, Box Office Hits, Indies and Imports, Movies A - Z FOUR STAR FILMS Top rated movies and made-for-TV films airing the week of the week of June 27 - July 3, 2021 American Graffiti (1973) Cinemax Mon. 4:12 a.m. The Exorcist (1973) TMC Sun. 8 p.m. Father of the Bride (1950) TCM Sun. 3:15 p.m. Finding Nemo (2003) Freeform Sat. 3:10 p.m. Forrest Gump (1994) Paramount Mon. 7 p.m. Paramount Mon. 10 p.m. VH1 Wed. 4 p.m. VH1 Wed. 7:30 p.m. Giant (1956) TCM Mon. 3 a.m. Glory (1989) Encore Sun. 11:32 a.m. Encore Sun. 9 p.m. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1967) Sundance Sun. 3:30 p.m. L.A. Confidential (1997) Encore Sun. 7:39 a.m. Encore Sun. 11:06 p.m. The Lady Vanishes (1938) TCM Sun. 3:30 a.m. The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) TCM Sun. 10:45 a.m. The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) TCM Sun. 11:15 p.m. Monsieur Hulot's Holiday (1953) TCM Mon. 8:30 p.m. North by Northwest (1959) TCM Sat. 12:15 p.m. Once (2006) Cinemax Mon. 2:44 a.m. Ordinary People (1980) EPIX Tues. 3:45 p.m. Psycho (1960) TCM Sun. 5 p.m. Rear Window (1954) TCM Sat. 7:15 p.m. Saving Private Ryan (1998) BBC America Wed. 8 p.m. BBC America Thur. 4 p.m. Shadow of a Doubt (1943) TCM Sat. 9:15 p.m. -

The Karate Kid Part Iii & the Next Karate Kid

THE KARATE KID PART III & THE NEXT KARATE KID - DOUBLE FEATURE - BD Short Synopsis: It’s a karate combo as the 3rd and 4th installments of the successfully Karate Kid franchise are paired together in one nostalgic Blu-ray collection! Karate Kid III - Daniel (Ralph Macchio) and Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) take up where they left off, returning from Okinawa and hoping for a peaceful life in their bonsai shop. But their serenity is shattered when Daniel is blackmailed into competing against the vicious “Bad Boy of Karate,” Mike Barnes (Sean Kanan). The Next Karate Kid - Mr. Miyagi is back and he takes a new pupil under his wing, troubled teenager Julie Pierce (Oscar®-winner Hillary Swank) who learns to control the grief and anger from the loss of her parents with the discipline of karate. Critic Quotes/Reviews: Karate Kid III - “…a high school Rocky, the underdog triumphant.“ – Caryn James, The New York Times The Next Karate Kid – “…a good coming of age story with the Karate Kid feel.” – Earl Cressey, DVD Talk Target Audience: 80s Movie Buffs, Action Fans, Viewers of Cobra Kai Notable Cast/Crew: Ralph Macchio (The Outsiders, Cobra Kai), Pat Morita, Hilary Swank (FX’s, Trust, What They Had) Key selling points: • Cobra Kai Season 2 premieres in early 2019 starring Ralph Macchio and William Zabka. • The Karate Kid franchise has generated over $420m at the box office and has sold over 6.8m units on DVD and Blu-ray. Clip Link: https://youtu.be/aBc38Lg3v1w Website Link: https://www.millcreekent.com/karate-kid-part-3-the-the-next-karate-kid-double- feature-blu-ray.html Title UPC Item # Format Genre SRP Aspect Ratio Rating Runtime # Disc The Karate Kid Part III & The Next Karate Kid - Double Feature – BD 683904633835 63383 Blu-ray Action $14.98 Widescreen PG 3 hr 39 min 1. -

CITIZ EN Make a Significant Impact in the 2008 Elections

~PACIFIC Voting Power Asian Pacific Americans ~ ~CITIZ EN make a significant impact in the 2008 elections. JACL challenges U.S. detentions. - p.\(;E 3 Equality. Lost: Same-sex Marriage is ~ Civil ·Rights Issue of the 21 st Century The elections are over, but workers return to their nonnallives, Tun for many couples the battle and Larry need to fight on towards an JACL to Continue to Press has just begun. uncertain future. To illustrate their cause, Aaron's color for Marriage Equality By LYNDA LIN ful crayon artwork urging people to vote Following passage of Proposition 8 in Assistant Editor "no" on Proposition 8 still hangs in the California, the JACL has joined with other civil front window of their home. rights groups to subrnit an amicus brief in sup It's been a painful few weeks for For them and many other same-sex port of the Petition for Writ Mandate in the case Tim Ky and his husband Larry couples, Nov. 4 marked both a major of Strauss, et al v. Horton, et al. Riesenbach. After California voters milestone in the fight for equality with the The Writ requests that the Calif. Supreme reinstated the ban on same-sex mar election of the nation's first African Court issue an order invalidating Proposition 8 in riages, their six-year-old son Aaron American president and a major setback its entirety. asked, "Will you pretend you're not with the passage of Proposition 8 in As an amici, JACL supports the petitioners' gay?" California and similar constitutional bans claim that no Californian should be denied equal "No," Tun responded. -

Aspectos Educacionais Do Karate: Discutindo Suas Representações No Cinema1

SEÇÃO: ARTIGOS Aspectos educacionais do karate: discutindo suas representações no cinema1 Rafael Cava Mori2 ORCID: 0000-0001-6301-2795 Gilmar Araújo de Oliveira3 ORCID: 0000-0002-7617-6235 Resumo O karate é uma luta originária de Okinawa, ilha ao sul do Japão. Historicamente, atravessou três períodos: a partir do século XVII, como bujutsu, técnica clandestina de luta; depois, como budo, quando foi convertido em luta tradicional japonesa, em fins do século XIX, propugnando valores educacionais e identitários; e finalmente, como esporte de luta, quando foi associado a performance motora e competitividade, no século XX. Ao considerar o papel do karate como veiculador de valores de um Japão idealizado – japonesidade –, este trabalho analisa representações cinematográficas dessa luta. A análise focou nos aspectos educativos retratados nos filmes, a série estadunidense The karate kid e o japonês Kuro obi, sendo conduzida conforme três categorias: a relação entre teoria e prática; ruídos e conflitos entre professor e aluno; e formação do aluno como futuro professor. Os resultados revelam que as obras criticam a esportivização do karate, enfatizando a representação de aspectos educacionais associados aos períodos do bujutsu e, principalmente, do budo. Também, colaboram para reafirmar e atualizar a japonesidade, ao tratar os princípios do budo e sua transmissão educacional de forma idealizada, sem aludir a seu caráter moderno. Ainda, os filmes apresentam divergências em relação à proposta contemporânea de uma pedagogia das lutas, fundamentada na ciência da motricidade humana. Por outro lado, as produções cinematográficas contribuem para a área educacional na medida em que possibilitam discussões a respeito dos processos formativos e seus percalços, retratados de forma original, recorrendo aos conceitos de yin/ yang relacionados aos princípios zen -budistas do budo.