57 Folk Horror, Ostension and Robin Redbreast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marble Hornets, the Slender Man, and The

DIGITAL FOLKLORE: MARBLE HORNETS, THE SLENDER MAN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF FOLK HORROR IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Dana Keller B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Dana Keller, 2013 Abstract In June 2009 a group of forum-goers on the popular culture website, Something Awful, created a monster called the Slender Man. Inhumanly tall, pale, black-clad, and with the power to control minds, the Slender Man references many classic, canonical horror monsters while simultaneously expressing an acute anxiety about the contemporary digital context that birthed him. This anxiety is apparent in the collective legends that have risen around the Slender Man since 2009, but it figures particularly strongly in the Web series Marble Hornets (Troy Wagner and Joseph DeLage June 2009 - ). This thesis examines Marble Hornets as an example of an emerging trend in digital, online cinema that it defines as “folk horror”: a subgenre of horror that is produced by online communities of everyday people— or folk—as opposed to professional crews working within the film industry. Works of folk horror address the questions and anxieties of our current, digital age by reflecting the changing roles and behaviours of the everyday person, who is becoming increasingly involved with the products of popular culture. After providing a context for understanding folk horror, this thesis analyzes Marble Hornets through the lens of folkloric narrative structures such as legends and folktales, and vernacular modes of filmmaking such as cinéma direct and found footage horror. -

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018)

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Contents ARTICLES Mother, Monstrous: Motherhood, Grief, and the Supernatural in Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Médée Shauna Louise Caffrey 4 ‘Most foul, strange and unnatural’: Refractions of Modernity in Conor McPherson’s The Weir Matthew Fogarty 17 John Banville’s (Post)modern Reinvention of the Gothic Tale: Boundary, Extimacy, and Disparity in Eclipse (2000) Mehdi Ghassemi 38 The Ballerina Body-Horror: Spectatorship, Female Subjectivity and the Abject in Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) Charlotte Gough 51 In the Shadow of Cymraeg: Machen’s ‘The White People’ and Welsh Coding in the Use of Esoteric and Gothicised Languages Angela Elise Schoch/Davidson 70 BOOK REVIEWS: LITERARY AND CULTURAL CRITICISM Jessica Gildersleeve, Don’t Look Now Anthony Ballas 95 Plant Horror: Approaches to the Monstrous Vegetal in Fiction and Film, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Angela Tenga Maria Beville 99 Gustavo Subero, Gender and Sexuality in Latin American Horror Cinema: Embodiments of Evil Edmund Cueva 103 Ecogothic in Nineteenth-Century American Literature, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Matthew Wynn Sivils Sarah Cullen 108 Monsters in the Classroom: Essays on Teaching What Scares Us, ed. by Adam Golub and Heather Hayton Laura Davidel 112 Scottish Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion, ed. by Carol Margaret Davison and Monica Germanà James Machin 118 The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Catherine Spooner, Post-Millennial Gothic: Comedy, Romance, and the Rise of Happy Gothic Barry Murnane 121 Anna Watz, Angela Carter and Surrealism: ‘A Feminist Libertarian Aesthetic’ John Sears 128 S. T. Joshi, Varieties of the Weird Tale Phil Smith 131 BOOK REVIEWS: FICTION A Suggestion of Ghosts: Supernatural Fiction by Women 1854-1900, ed. -

Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic

‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Irene Bulla All rights reserved ABSTRACT ‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla This dissertation analyzes the ways in which monstrosity is articulated in fantastic literature, a genre or mode that is inherently devoted to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable. Through the readings of a number of nineteenth-century texts and the analysis of the fiction of two twentieth-century writers (H. P. Lovecraft and Tommaso Landolfi), I show how the intersection of the monstrous theme with the fantastic literary mode forces us to consider how a third term, that of language, intervenes in many guises in the negotiation of the relationship between humanity and monstrosity. I argue that fantastic texts engage with monstrosity as a linguistic problem, using it to explore the limits of discourse and constructing through it a specific language for the indescribable. The monster is framed as a bizarre, uninterpretable sign, whose disruptive presence in the text hints towards a critique of overconfident rational constructions of ‘reality’ and the self. The dissertation is divided into three main sections. The first reconstructs the critical debate surrounding fantastic literature – a decades-long effort of definition modeling the same tension staged by the literary fantastic; the second offers a focused reading of three short stories from the second half of the nineteenth century (“What Was It?,” 1859, by Fitz-James O’Brien, the second version of “Le Horla,” 1887, by Guy de Maupassant, and “The Damned Thing,” 1893, by Ambrose Bierce) in light of the organizing principle of apophasis; the last section investigates the notion of monstrous language in the fiction of H. -

Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 Pm

1 Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 p.m. - 3:15 p.m. Pre-Opening Refreshment Ballroom Foyer ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 3:30 p.m. - 4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Ballroom Host: Jeri Zulli, Conference Director Welcome from the President: Dale Knickerbocker Guest of Honor Reading: Jeff VanderMeer Ballroom “DEAD ALIVE: Astronauts versus Hummingbirds versus Giant Marmots” Host: Benjamin J. Robertson University of Colorado, Boulder ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 4:30 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 1. (GaH) Cosmic Horror, Existential Dread, and the Limits of Mortality Belle Isle Chair: Jude Wright Peru State College Dead Cthulhu Waits Dreaming of Corn in June: Intersections Between Folk Horror and Cosmic Horror Doug Ford State College of Florida The Immortal Existential Crisis Illuminates The Monstrous Human in Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf Jordan Moran State College of Florida Hell . With a Beach: Christian Horror in Michael Bishop's "The Door Gunner" Joe Sanders Shadetree Scholar 2 2. (CYA/FTV) Superhero Surprise! Gender Constructions in Marvel, SpecFic, and DC Captiva A Chair: Emily Midkiff Northeastern State University "Every Woman Has a Crazy Side"? The Young Adult and Middle Grade Feminist Reclamation of Harley Quinn Anastasia Salter University of Central Florida An Elaborate Contraption: Pervasive Games as Mechanisms of Control in Ernest Cline's Ready Player One Jack Murray University of Central Florida 3. (FTFN/CYA) Orienting Oneself with Fairy Stories Captiva B Chair: Jennifer Eastman Attebery Idaho State University Fairy-Tale Socialization and the Many Lands of Oz Jill Terry Rudy Brigham Young University From Android to Human – Examining Technology to Explore Identity and Humanity in The Lunar Chronicles Hannah Mummert University of Southern Mississippi The Gentry and The Little People: Resolving the Conflicting Legacy of Fairy Fiction Savannah Hughes University of Maine, Stonecoast 3 4. -

NVS 10-1 Announcements Page;

Announcements: CFPs, conference notices, & current & forthcoming projects and publications of interest to neo-Victorian scholars (compiled by the NVS Editorial Team) ***** CFPs: Journals, Special Issues & Collections (Entries that are only listed, without full details, were highlighted in a previous issue of NVS. Entries are listed in order of abstract/submission deadlines.) In Frankenstein’s Wake Special Issue of The International Review of Science Fiction (2018) Submissions due: 29 January 2018. Articles should be approximately 6,000 words long and written in accordance with the style sheet available at the SF Foundation website and submitted to journaleditor@sf- foundation.org. Journal website: https://www.sf- foundation.org/publications/foundation/index.html Dickens and Wills; Engaging Dickens; Obscure or Under-read Dickens 3 Special Issues of Dickens Quarterly Submissions due: 1 September 2018. Please submit articles in two forms: an electronic version to [email protected] and a hard copy to the journal’s address: 100 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 7NE England. Essays should range between 6,000 and 8,000 words, although shorter submissions will be considered. For further instructions, see ‘Dickens Quarterly: A Guide for Contributors’, available as a PDF file from the website of the Dickens Society dickenssociety.org. Journal Website: https://www.press.jhu.edu/journals/dickens-quarterly Neo-Victorian Studies 10:1 (2017) pp. 193-200 194 Announcements _____________________________________________________________ Perspectives on the Non-Human in Literature and Culture (Routledge) Submissions due: no deadline. Please address any questions about this series or the submission process to Karen Raber at [email protected]. Series website: https://www.routledge.com/Perspectives-on-the-Non- Human-in-Literature-and-Culture/book-series/PNHLC Journal of Historical Fictions Submissions due: no deadline. -

Mark Gatiss Got His Ideas for the Medusa Touch

FINAL CUT When cult TV comedy The League Of Gentlemen devoted an episode to bizarre SM games in a provincial B&B, it looked like someone on the team must have remarkable inside knowledge. So we sent Liz Tray to find out just where writer Mark Gatiss got his ideas for The Medusa Touch invention. It turns out that Mark based his character on a chance meeting at a wedding. “He was a photographer and would say things like [in sleazy voice] ‘I’d like to photograph you, you’re very beautiful – let me tell you about the recdum, a beautiful organ’. He actually said ‘recdum’ with a ‘d’!” So none of this remarkable tale was based on actual personal experience of the perv scene? Apparently not. “But,” Mark recalls, “I did cover a Dungeon In The Sky event for Boyz magazine about six years ago. I was not trying to be cynical but it was so funny. I Deep breaths: Daddy (Steve Pemberton) ready to embark on a went to a spanking workshop and it was little light asphyxiation with his Medusa-suited neophytes gloriously unerotic. The demonstration irst televised in 1999, The League his head underwater. So I drowned him, was on a pillow instead of a bottom and Of Gentlemen has become a fucked him and went home. No, I’m just it was covered with white chalk marks FBritish TV comedic institution kidding! We needed a way that all the showing you how to improve your aim. It and a cult hit worldwide. So we clearly characters would die.” was like a WI jam-making workshop.” couldn’t ignore the League’s recent sortie Inspiration for the inflatable suits into the world of extreme SM breath came, unsurprisingly, from late night TV. -

5 July 2013 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 29 JUNE 2013 Thinking 'Is That It?', and Stayed in India for a Further 18 Months

Radio 4 Listings for 29 June – 5 July 2013 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 29 JUNE 2013 thinking 'is that it?', and stayed in India for a further 18 months. how we make it. Today 100 hours of video are uploaded onto YouTube every minute... six billion hours of video are watched SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b02ypklq) On this walk, around Cannock Chase in Staffordshire, Tara is every month. And by the time you finish reading this The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. accompanied by his son, Clive, Clive's wife, Jodie, and their description, those figures may already be out of date. Followed by Weather. two children. The BBC Arts Editor, Will Gompertz, in searching for the next Producer: Karen Gregor. generation of cultural Zeitgeisters, meets the people who are SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b02ymgwl) moving YouTube up to the next level: 'YouTubers' like David Mitchell - The Reason I Jump Benjamin Cook, who posts regular episodes of 'Becoming SAT 06:30 Farming Today (b0366wml) YouTube' on his channel Nine Brass Monkeys; Andy Taylor, Episode 5 Farming Today This Week who's 'Little Dot Studios' aims to bridge the gap between television and YouTube; and Ben McOwen Wilson who is By Naoki Higashida A third of people living in rural areas face poverty, despite the Director of Content Partnerships for YouTube in Europe. Translated by David Mitchell and KA Yoshida, and introduced fact that most of them are in work. by David Mitchell And that's not all that's worrying. People in their thirties are Producer: Paul Kobrak. -

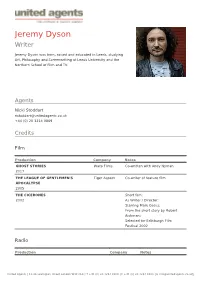

Jeremy Dyson Writer

Jeremy Dyson Writer Jeremy Dyson was born, raised and educated in Leeds, studying Art, Philosophy and Screenwriting at Leeds University and the Northern School of Film and TV. Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Film Production Company Notes GHOST STORIES Warp Films Co-written with Andy Nyman 2017 THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S Tiger Aspect Co-writer of feature film APOCALYPSE 2005 THE CICERONES Short film; 2002 As Writer / Director; Starring Mark Gatiss; From the short story by Robert Aickman; Selected for Edinburgh Film Festival 2002 Radio Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] THE UNSETTLED DUST: THE STRANGE STORIES BBC Radio 4 OF ROBERT AICKMAN 2011 RINGING THE CHANGES BBC Radio 4 Co-written with Mark 2000 Gatiss Adapted from the short story by Robert Aickman ON THE TOWN WITH THE LEAGUE OF BBC Radio 4 Co-writer GENTLEMEN Sony Silver Award 1997 Television Production Company Notes THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S BBC2 ANNIVERSARY SPECIALS 2017 TRACEY ULLMAN'S SHOW BBC1 2016 - 2017 PSYCHOBITCHES (SERIES 1 & 2) Tiger Aspect/Sky Arts Director/Co-writer 2012 - 2015 Nominated for two British Comedy Awards 2013; Winner of the Rose d'Or for Best TV Comedy THE ARMSTRONG & MILLER Hat Trick / BBC1 Series 1, 2 & 3 SHOW Script Editor/ Writer 2007 - 2010 BAFTA Award Best Comedy 2010 BILLY GOAT Hat Trick / BBC 1 x 60' 2008 Northern Ireland /BBC1 FUNLAND BBC2 Co-creator, co-writer and Associate 2006 -

SCB Distributors Spring 2013 Catalog

SCB DISTRIBUTORS SPRING 2013 SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT SCB DISTRIBUTORS IS Birch Bench Press PROUD TO INTRODUCE Bongout Cassowary Press Coffee Table Comics Déjà vu Lifestyle Creations Grapevine Press Honest Publishing Penny-Ante Editions SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT The cover image is from page 113 of The Swan, published by Merlin Unwin, found on page 83 of this catalog. Catalog layout by Dan Nolte, based on an original design by Rama Crouch-Wong My First Kafka Runaways, Rodents, & Giant Bugs By Matthue Roth Illustrated by Rohan Daniel Eason “Matthue Roth is the kind of person you move to San Francisco to meet.” – Kirk Read, How I Learned to Snap An adaptation of 3 Kafka stories into startling, creepy, fun stories for all ages, featuring: ■ runaway children who meet up with monsters ■ a giant talking bug ■ a secret world of mouse-people This subversive debut takes a place alongside Sendak, Gorey, and Lemony Snicket. ■ endorsed by Neil Gaiman Matthue Roth wrote Yom Kippur a Go-Go and Never Mind the Goldbergs, nominated as an ALA Best Book and named a Best Book by the NY Public Library. He produced the animated series G-dcast, and wrote the feature film 1/20. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the chef KAFKA, REIMAGINED AND ILLUSTRATED Itta Roth. www.matthue.com Rohan Daniel Eason, who studied painting in London, illustrated Anna and the Witch's Bottle and Tancredi. My First Kafka ISBN: 978-1-935548-25-6 $18.95 | hardcover 8 x 10 32 pages 32 B&W Illustrations Ages 7 & Up June Children’s Picture Book Literature ONE PEACE BOOKS SCB DISTRIBUTORS..|..SPRING 2013..|..1 Terminal Atrocity Zone: Ballard J.G. -

A Field in England

INSIGHT REPORT A Field In England bfi.org.uk 1 Contents Introduction 3 Executive Summary 4 Section One: Overview 5 Section Two: Planning and Execution 6 Section Three: Results 9 Section Four: Conclusions 14 2 INTRODUCTION The following is the report on the DAY AND DATERELEASEOFA Field In England. It uses a wide range of data to measure performance on all platforms, and tries to address the key questions about the significance of the release. A Field In England was released on 5 July 2013 The conclusions are based on an objective view on cinema screens, DVD, VOD and free terrestrial of the data, interviews both before and after broadcast on Film4. the film’s release, and on experience of the UK distribution and exhibition market. The BFI Distribution Fund supported the release of the project with £56,701, which contributed The report evaluates the performance of an to a P&A spend of £112,000. The total production individual film but it also tries to explain the budget was £316,879. context of the release and to suggest lessons for other films trying similar strategies. This report uses a number of measures to assess the success of the release: s "OXOFFICEREPORTSDAILYFOROPENING weekend, weekly thereafter) s /PENINGWEEKENDEXITPOLLSFROM&IRST-OVIES )NTERNATIONALFOR0ICTUREHOUSECINEMA s $6$"LU 2AYSALES/PENINGWEEKEND s 4ELEVISIONRATINGS s /NLINEMONITORING"RILLIANT.OISEFOR Picturehouse Cinemas) 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY sA Field In EnglandISANEXPERIMENTAL GENRE s4HEPRIMARYAUDIENCEWAS!"#n YEARS busting film set in the English Civil War OLD ANDFREQUENTCINEMAGOERSINTHE ANDDIRECTEDBY"EN7HEATLEYDown Terrace, bracket, who might have already been aware Kill List, Sightseers). of Wheatley’s work. -

Man up – Biographies

Presents MAN UP A film by Ben Palmer (88 min., UK, 2015) Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia LOGLINE When Nancy is mistaken for Jack’s blind date under the clock at Waterloo Station, she decides to take fate into her own hands and just go with it. What could possibly go wrong? MAN UP is an honest, heart-warming romantic comedy about taking chances and rolling with the consequences. One night, two people, on a first date like no other... SHORT SYNOPSIS Meet Nancy (Lake Bell): 34, single, hung-over, and exhausted by her well meaning but clueless friends’ continual matchmaking. 10 times bitten, 100 times shy, after an especially disastrous set-up at her friends’ engagement party, Nancy is basically done with dating. She’s reached the end of her rope, and is more than happy to hole up, seal up, and resign herself to a life alone. That is until Jack (Simon Pegg) mistakes Nancy for his blind date under the clock at Waterloo Station, and she does the unthinkable and just… goes with it. Because what if pretending to be someone else finally makes her man up, and become her painfully honest, awesomely unconventional, and slightly unstable true self? Best just to let the evening unfold, roll with the consequences, and see if one unpredictable, complicated, rather unique night can bring these two messy souls together. -

Digital Cinema and the Legacy of George Lucas

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Digital cinema and the legacy of George Lucas Willis, Daniel Award date: 2021 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. We exercise best efforts on our behalf and, in such instances, encourage the individual to consult the physical thesis for further information.