Thomas Hornsby Ferril

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

American Heritage Day

American Heritage Day DEAR PARENTS, Each year the elementary school students at Valley Christian Academy prepare a speech depicting the life of a great American man or woman. The speech is written in the first person and should include the character’s birth, death, and major accomplishments. Parents should feel free to help their children write these speeches. A good way to write the speech is to find a child’s biography and follow the story line as you construct the speech. This will make for a more interesting speech rather than a mere recitation of facts from the encyclopedia. Students will be awarded extra points for including spiritual application in their speeches. Please adhere to the following time limits. K-1 Speeches must be 1-3 minutes in length with a minimum of 175 words. 2-3 Speeches must be 2-5 minutes in length with a minimum of 350 words. 4-6 Speeches must be 3-10 minutes in length with a minimum of 525 words. Students will give their speeches in class. They should be sure to have their speeches memorized well enough so they do not need any prompts. Please be aware that students who need frequent prompting will receive a low grade. Also, any student with a speech that doesn’t meet the minimum requirement will receive a “D” or “F.” Students must portray a different character each year. One of the goals of this assignment is to help our children learn about different men and women who have made America great. Help your child choose characters from whom they can learn much. -

Dr. Sperling Blasts Kerr for Remarks

San n1E- Request Voucher Po- Today's Weather and Santa t Lira : No rain Students receising benefit% un- ar- today and tomorrow except der Public Law 634 (War go, light rain in extreme north; Orphans) should file souchers temperatures are expected to PARTAN I LY for November in the Regis- DA be near normal. Southwest trar's Office, ADM102 window winds 5-10 mph. SAN JOSE STATE COLLEGE No. 9. Vol. 63 1111110 SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA. MONDAY, DECEMBER 6, 1965 No. 48 Prof Blasts 'Make It Funny' e State College Dr. Sperling Blasts Hiring Policy Another Draft Story An SJS professor has accused By RICH THAW "You are hereby ordered for (c) deferment "might be ow state college administrators of en- Kerr for Remarks Spartan Daily Saigon(?) induction into the Armed Forces in the afternon mailing." couraging the hiring of student Corespondent of the United States, and to re- The opening to the featur, Dr. John Sperling, SJS assistant puses to institute sununer pro- ally, we will support it. If it does instructors to teach classes that Says the Editor: port at 1654 The Alameda, San story might be "A funny thin. professor of humanities, has ac- grams. not, we will insist on changes or should be taught by more experi- "Thaw, write another story Jose, California, on Dec. 15, happened to me on the way t, cused University of California Pres. Gov. Edmund Brown echoed the oppose it. We certainly will not enced professors, and the overload- on the draft. lalake it humorous. 1965 at 6 a.m. (morning). -

13.09.2018 Orcid # 0000-0002-3893-543X

JAST, 2018; 49: 59-76 Submitted: 11.07.2018 Accepted: 13.09.2018 ORCID # 0000-0002-3893-543X Dystopian Misogyny: Returning to 1970s Feminist Theory through Kelly Sue DeConnick’s Bitch Planet Kaan Gazne Abstract Although the Civil Rights Movement led the way for African American equality during the 1960s, activist women struggled to find a permanent place in the movement since key leaders, such as Stokely Carmichael, were openly discriminating against them and marginalizing their concerns. Women of color, radical women, working class women, and lesbians were ignored, and looked to “women’s liberation,” a branch of feminism which focused on consciousness- raising and social action, for answers. Women’s liberationists were also committed to theory making, and expressed their radical social and political ideas through countless essays and manifestos, such as Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto (1967), Jo Freeman’s BITCH Manifesto (1968), the Redstockings Manifesto (1969), and the Radicalesbians’ The Woman-Identified Woman (1970). Kelly Sue DeConnick’s American comic book series Bitch Planet (2014–present) is a modern adaptation of the issues expressed in these radical second wave feminist manifestos. Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future ruled by men where disobedient women—those who refuse to conform to traditional female gender roles, such as being subordinate, attractive (thin), and obedient “housewives”—are exiled to a different planet, Bitch Planet, as punishment. Although Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future, as this article will argue, it uses the theoretical framework of radical second wave feminists to explore the problems of contemporary American women. 59 Kaan Gazne Keywords Comic books, Misogyny, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Dystopia Distopik Cinsiyetçilik: Kelly Sue DeConnick’in Bitch Planet Eseri ile 1970’lerin Feminist Kuramına Geri Dönüş Öz Sivil Haklar Hareketi Afrikalı Amerikalıların eşitliği yolunda önemli bir rol üstlenmesine rağmen, birçok aktivist kadın kendilerine bu hareketin içinde bir yer edinmekte zorlandılar. -

Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books

The Visualization of the Twisted Tongue: Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books JEFFREY K. JOHNSON HERE IS A WELL-ESTABLISHED TRADITION WITHIN THE ENTERTAINMENT and publishing industries of depicting mentally and physically challenged characters. While many of the early renderings were sideshowesque amusements or one-dimensional melodramas, numerous contemporary works have utilized characters with disabilities in well- rounded and nonstereotypical ways. Although it would appear that many in society have begun to demand more realistic portrayals of characters with physical and mental challenges, one impediment that is still often typified by coarse caricatures is that of stuttering. The speech impediment labeled stuttering is often used as a crude formulaic storytelling device that adheres to basic misconceptions about the condition. Stuttering is frequently used as visual shorthand to communicate humor, nervousness, weakness, or unheroic/villainous characters. Because almost all the monographs written about the por- trayals of disabilities in film and television fail to mention stuttering, the purpose of this article is to examine the basic categorical formulas used in depicting stuttering in the mainstream popular culture areas of film, television, and comic books.' Though the subject may seem minor or unimportant, it does in fact provide an outlet to observe the relationship between a physical condition and the popular conception of the mental and personality traits that accompany it. One widely accepted definition of stuttering is, "the interruption of the flow of speech by hesitations, prolongation of sounds and blockages sufficient to cause anxiety and impair verbal communication" (Carlisle 4). The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 41, No. -

World Stage Curriculum

World Stage Curriculum Washington Irving’s Tour 1832 TEACHER You have been given a completed world stage and a world stage that your students can complete. This world stage is a snapshot of the world with Oklahoma, Cherokee Nation and Muscogee Creek Nation, at its center. The Pawnee, Comanche, and Kiowa were out to the west. Europe is to the north and east. Africa is to the south and east. South America is south and a bit east. Asia and the Pacific are to the west. Use a globe to show your students that these directions are accurate. Students - Directions 1. Your teacher will assign one of these actors to you. 2. After research, note the age of the actor in 1832, the year that Irving, Ellsworth, Pourtalès, and Latrobe took a Tour on the Oklahoma prairies. 3. Place the name and age of the actor in the right place on the World Stage. 4. Write a biographical sketch about the actor. 5. Make a report to the class, sharing the biographical sketch, the age of the actor in 1832, and the place the actor was at that time. 6. Listen to all the other reports and place all of the actors in their correct locations with their correct ages in 1832. Students - Information 1. The majority of the characters can be found in your public library in biographies and encyclopedia. You will need a library card to access this information. There is enough information about each actor for a biographical sketch. 2. Other actors can be found on the Internet. -

Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris Triseriata), Great Lakes/ St

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata), Great Lakes/ St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population, in Canada Western Chorus Frog 2014 1 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2014. Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata), Great Lakes / St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population, in Canada [Proposed], Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series, Environment Canada, Ottawa, v + 46 pp For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca). Cover illustration: © Raymond Belhumeur Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de la rainette faux-grillon de l’Ouest (Pseudacris triseriata), population des Grands Lacs et Saint-Laurent et du Bouclier canadien, au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog 2014 (Great Lakes / St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population) PREFACE The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years of the publication of the final document on the Species at Risk Public Registry. -

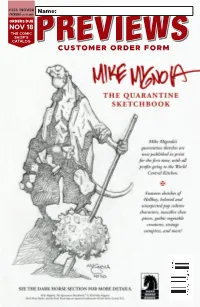

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

Mountain Men on Film Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 1-1-2016 Mountain Men on Film Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Citation Information Hall, Kenneth Estes. 2016. Mountain Men on Film. Studies in the Western. Vol.24 97-119. http://www.westernforschungszentrum.de/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mountain Men on Film Copyright Statement This document was published with permission from the journal. It was originally published in the Studies in the Western. This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/596 Peter Bischoff 53 Warshow, Robert. "Movie Chronicle: The Western." Partisan Re- view, 21 (1954), 190-203. (Quoted from reference number 33) Mountain Men on Film 54 Webb, Walter Prescott. The Great Plains. Boston: Ginn and Kenneth E. Hall Company, 1931. 55 West, Ray B. , Jr., ed. Rocky Mountain Reader. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1946. 56 Westbrook, Max. "The Authentic Western." Western American Literatu,e, 13 (Fall 1978), 213-25. 57 The Western Literature Association (sponsored by). A Literary History of the American West. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1987. -

Tough Paradise-Book Summaries

WHY AM I READING THIS? In 1995 the Idaho Humanities Council received an Exemplary Award from the National Endowment for the Humanities to conduct a special project highlighting the literature of Idaho and the Intermountain West. “Tough Paradise” explores the relationships between place and human psychology and values. Representing various periods in regional history, various cultural groups, various values, the books in this theme highlight the variety of ways that humans may respond to the challenging landscape of Idaho and the northern Intermountain West. Developed by Susan Swetnam, Professor of English, Idaho State University (1995) Book List 1. Balsamroot: A Memoir by Mary Clearman Blew 2. Bloodlines: Odyssey of a Native Daughter by Janet Campbell Hale 3. Buffalo Coat by Carol Ryrie Brink 4. Heart of a Western Woman by Leslie Leek 5. Hole in the Sky by William Kittredge 6. Home Below Hell’s Canyon by Grace Jordan 7. Honey in the Horn by H. L. Davis 8. Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson 9. Journal of a Trapper Osborne Russell 10. Letters of a Woman Homesteader by Elinore Pruitt Stewart 11. Lives of the Saints in Southeast Idaho by Susan H. Swetnam 1 12. Lochsa Road by Kim Stafford 13. Myths of the Idaho Indians by Deward Walker, Jr. 14. Passages West: Nineteen Stories of Youth and Identity by Hugh Nichols 15. Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place by Terry Tempest Williams 16. Sheep May Safely Graze by Louie Attebery 17. Stories That Make the World by Rodney Frey 18. Stump Ranch Pioneer by Nelle Portrey Davis 19. -

From the Files of the Museum

The Henry L. Ferguson Museum Newsletter Vol. 27, No. 1 • Spring 2012 (631) 788-7239 • P.O. Box 554 Fishers Island, NY 06390 • [email protected] • www.fergusonmuseum.org From the President Spring is well underway on Fishers Island as I write this new annual show featuring the artwork of Charles B. Fer- annual greeting on behalf of the Museum. After one of the guson. This promises to be one of our most popular shows mildest winters in my memory, spring has brought a strange and a great tribute to Charlie. We are also mounting a special mix of weather conditions with temperatures well into the exhibit that honors the wonderful legacy of gardens and par- 80s during March followed by chilly days in April and May. ties at Bunty and the late Tom Armstrong’s Hoover Hall and For those interested in phenology, the bloom time of many of Hooverness. We hope that all will come celebrate with us at our plants has been well ahead of schedule this year. The early our opening party on Saturday, June 30th, 5 to 7 p.m. bloom time raises questions regarding the first appearances of The Land Trust continues to pursue land acquisitions un- butterflies and other pollinators and the first arrivals of migra- der the able guidance of our Vice-President Bob Miller. One tory birds. Will these events coincide with bloom time as they of our recent projects is the management of Silver Eel Pre- have in the past or is the timing out of synch? It will be in- serve, a parcel of land that was purchased with open space teresting to track the timing of spring happenings as the years funding by the Town of Southold.