Cultural Trauma, the Nanking Massacre” and Chinese Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POST SOLANT AMITY with the Members of “G” Company, 2Nd Battalion, 6Th Marine Regiment Volume 7, Issue 3

POST SOLANT AMITY With the Members of “G” Company, 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment Volume 7, Issue 3 September 2009 Trivia Question 2: Uh, on a Sailor’s Unfaded Memories of Solant Amity I anchor at the mouth to the harbor, effectively blocking her escape, lighter note: Did Chesty Puller (Editor’s note: The PSA newsletter clear submarine, USS Nautilus, had should she try. have a tattoo? (Answer 2, page 4) is now in its seventh year of publica- been tailing the Santa Maria at the tion. Before that only emails flashed time. The next day we docked and stayed The only radio traffic that I passed back and forth among our lot. A few there for four days, where a drink was a request for the whale boat to months back, Tom DeLange reached We at first and unexpectedly en- cost 100 cruzeiros...a DIME? come back and pick us up. Again, out to our website and when asked countered Vera Cruz, the Santa no answers were provided and to provide thoughts of our distant Maria‘s sister ship. The result: a questions were discouraged. The yesteryear connection he responded full and resounding ―General Quar- upside? Well, I didn‘t have to dig a with a flood of “stuff” both interest- ters! General Quarters! All hands foxhole. :-) ing and instructional of those six man your battle stations. This is not months we all shared so VERY long a drill.‖ From my station as star- Speaking of jogging memories, ago. Enjoy!) board lookout I watched the pas- wasn‘t it in Dakar, Senegal that a The Belgian Congo was where I got certain group of Marines dropped During the Santa Maria incident I sengers of the Vera Cruz happily to go ashore and play Marine. -

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

Eugene B. Sledge MBM August 2020 FINAL.Pdf (3.688

HISTORY | LEGENDS Eugene B. Sledge and Mobile: 75 Years After “The War” Mobilian Eugene Sledge is recognized the world over as a USMC combat veteran of World War II, but there is even more to know, and admire, about “Ugin” of Georgia Cottage. text by AARON TREHUB • photos courtesy AUBURN UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES xactly 75 years ago this spring, in May and June 1945, Mo- bile native and U.S. Marine Corps PFC Eugene Bondurant Sledge was fighting on Okinawa as a mortarman with Com- pany K, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment of the 1st Ma- Erine Division. Sledge was already a combat veteran by this time, having received his baptism of fire on Peleliu in September and October 1944. He was 21 years old. Years later, Sledge described the fighting on Okinawa in mid-May 1945 and the recurring nightmares that it inspired. “The increasing dread of going back into action obsessed me,” he wrote. “It became the subject of the most tortuous and persistent of all the ghastly war nightmares that have haunted me for many, many years. The dream is always the same, going back up to the lines during the bloody, muddy month of May on Okinawa. It remains blurred and vague, but oc- casionally still comes, even after the nightmares about the shock and violence of Peleliu have faded and been lifted from me like a curse.” Nightmares haunted Sledge for decades after the war: as a com- bat veteran and student attending Alabama Polytechnic Institute (Auburn University) on the G.I. Bill in the late 1940s; as a young husband and father pursuing graduate degrees at API and the Uni- versity of Florida in the late 1950s; and as a professor of biology at the University of Montevallo from the 1960s through the 1980s. -

America's Military and the Struggle Between the Overseas And

C O R P O R A T I O N The Crisis Within America’s Military and the Struggle Between the Overseas and Guardian Paradigms Paula G. Thornhill For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1420 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9300-4 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface At some point during their military service, almost everyone who wears a uniform wonders about the gap between the military they thought they joined and the reality of the military in which they serve. -

Trauma and Mythologies of the Old West in the Western Novels Of

Trauma and Mythologies of the Old West in the Western Novels of Cormac McCarthy A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2012 Antony Harrison School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Abstract ........................................................................................ 3 Declaration/Copyright ..................................................................4 Acknowledgements ......................................................................5 Introduction ..................................................................................6 Chapter One: Trauma, Myth and the Quest Narrative in The Crossing..............63 Chapter Two: Trauma and Heroic Masculinity in All the Pretty Horses and Cities of the Plain................................111 Chapter Three: Trauma: Past, Present, Future and National Identity in No Country for Old Men and The Road........................................181 Conclusion.....................................................................................253 Bibliography..................................................................................262 Word Count: 83,426 2 Abstract This thesis explores how McCarthy uses figures of trauma to interrogate the creation of myth in three categories: mythic narrative, mythic masculinity, and mythic national identity. Focusing on McCarthy‟s five most recent novels, All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, Cities of the Plain, No Country for Old Men and The Road, I argue -

WWII Pacific PP.Pdf

Short Documentaries on War in the Pacific • The Pacific: Historical Background Part 1 (HBO) • The Pacific: Anatomy of a War (HBO) Japanese Aggression Builds • In the early 1900s Japan had a severe lack of natural resources. • Their plan was to invade and conquer neighboring lands that had the natural resources that they wanted. • Japanese expansion in East Asia began in 1931 with the invasion of Manchuria and continued in 1937 with a brutal attack on China. • On September 27, 1940, Japan signed a pact with Germany and Italy, thus entering the military alliance known as the “Axis Powers.” • The United States wanted to curb Japan Vs. the Japan’s aggressive actions. • They also wanted to force a United States withdrawal of Japanese forces from Manchuria and China. • So, the United States imposed economic sanctions on Japan. • Japan now faced severe shortages of oil, along with their shortage of other natural resources. • The Japanese were also driven by the ambition to displace the United States as the dominant Pacific power. • To solve these issues, Japan decided to attack the United States and British forces in Asia and seize the resources of Southeast Asia. Japan Attacks Pearl Harbor • However, because America is bigger and more powerful than Japan, a surprise assault is the only realistic way to defeat the U.S. • Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands on December 7, 1941. • When the first Japanese bombs struck Pearl Harbor shortly before eight in the morning, the American forces were utterly unprepared. • Anchored ships, such as the Nevada, the Utah, and the Arizona, provided easy targets for bombs and torpedoes. -

A Rhetorical History of the Office of Legal Counsel

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 A Rhetorical history of the Office of Legal Counsel William O’Donnal Saas University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Rhetoric Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Repository Citation Saas, William O’Donnal, "A Rhetorical history of the Office of Legal Counsel" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 321. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1547803 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF LEGAL COUNSEL by William O‟Donnal Saas Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Communication Studies Department of Communication Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by William O. -

Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2001 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, March 2004 Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi Laszlo Berkowits, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Tim Cole, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by István Deák, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Eva Hevesi Ehrlich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Charles Fenyvesi; Copyright © 2001 by Paul Hanebrink, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Albert Lichtmann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by George S. Pick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum In Charles Fenyvesi's contribution “The World that Was Lost,” four stanzas from Czeslaw Milosz's poem “Dedication” are reprinted with the permission of the author. Contents -

Filosofická Fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bakalářská diplomová práce Monika Křižánková 2014 2014 Křižánková Monika 2014 Monika Křižánková Hřbet Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Monika Křižánková Pacific War Experience of E.B. Sledge and R. Leckie: US Marines, Suffering Heroes, and Brave Victims Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Dušan Kolcún 2014 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 1 I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Dušan Kolcún; for his insightful comments, suggestions, and advice that were guiding my every step, thought, and word. But the greatest and the deepest gratitude is dedicated to my father who introduced me to the compelling stories hidden behind names such as Guadalcanal or Midway. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 5 1 The Second World War in American Literature ....................................................... 8 1.1 War Memoirs ................................................................................................... 10 1.2 With the Old Breed and Helmet for My Pillow ................................................ 14 2 Beyond the U.S. Marine Corps ............................................................................... 21 2.1 Robert -

Copyright by James Joshua Hudson 2015

Copyright by James Joshua Hudson 2015 The Dissertation Committee for James Joshua Hudson Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History Committee: Huaiyin Li, Supervisor Mark Metzler Mary Neuburger David Sena William Hurst River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History by James Joshua Hudson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Dedication For my good friend Hou Xiaohua River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History James Joshua Hudson, PhD. The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Huaiyin Li This work is a modern history of Changsha, the capital city of Hunan province, from the late nineteenth to mid twentieth centuries. The story begins by discussing a battle that occurred in the city during the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), a civil war that erupted in China during the mid nineteenth century. The events of this battle, but especially its memorialization in local temples in the years following the rebellion, established a local identity of resistance to Christianity and western imperialism. By the 1890’s this culture of resistance contributed to a series of riots that erupted in south China, related to the distribution of anti-Christian tracts and placards from publishing houses in Changsha. During these years a local gentry named Ye Dehui (1864-1927) emerged as a prominent businessman, grain merchant, and community leader. -

Navajo Code Talkers in WWII

CASUALTIES AT SAIPAN 0. CASUALTIES AT SAIPAN - Story Preface 1. NAVAJOS and THE LONG WALK 2. NAVAJO and the ANCESTRAL LANDS 3. NAVAJO FAMILY LIFE 4. LIFE on the NAVAJO RESERVATION 5. THE NAVAJO NATION 6. PHILIP JOHNSTON and the CODE TALKERS 7. MEET the NAVAJO CODE TALKERS 8. WEST LOCH DISASTER 9. AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT on SAIPAN 10. CODE TALKERS and the BATTLE of SAIPAN 11. BANZAI CHARGE at SAIPAN 12. HARI-KARI on SAIPAN 13. CASUALTIES AT SAIPAN 14. BATTLE of PELELIU - LANDINGS 15. CASUALTIES at PELELIU 16. SECRETS of the CODE TALKERS 17. BELATED HONORS This photo, taken by a member of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, depicts “Scenes of wreckage in the town of Garapan, Saipan, Island.” National Archives Identifier number 292588. Click on the image to expand its view. At 4:15 p.m. Saipan time, on July 9th, the island was officially declared "secured." Four months later, one hundred B-29s left Saipan for their first massive air raid over Tokyo. The Saipan casualty toll was stunning: Japanese known dead: 23, 811 Japanese dead in caves: "Uncounted thousands" Japanese Prisoners of war: 298 Korean Prisoners of war: 438 Americans wounded in action: 13,061 Americans killed in action: 3,225 Americans missing in action: 326 News that Saipan had been lost to the Allies shocked the Japanese government. The Premier, Hideki Tojo, resigned. So did his entire cabinet. (Tojo was hanged for war crimes in 1948.) General Holland Smith declared that the victory on Saipan "opened the way to the home islands." The famous Japanese General Saito had observed (scroll down 95%) that "the fate of the Empire will be decided in this one action." As key participants in the Allied effort, the Navajo code talkers played a fundamental role in causing another Japanese admiral to observe: Our war was lost with the loss of Saipan. -

Accession Sheet

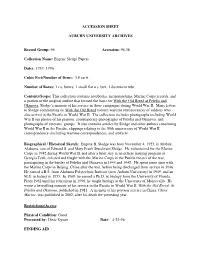

ACCESSION SHEET AUBURN UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES Record Group: 96 Accession: 96-38 Collection Name: Eugene Sledge Papers Dates: 1937- 1996 Cubic Feet/Number of Items:. 3.8 cu ft. Number of Boxes: 3 r.c. boxes, 1 small flat o.s. box, 1 document tube Contents/Scope: This collection contains notebooks, memorandums, Marine Corps records, and a portion of the original outline that formed the basis for With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, Sledge’s memoir of his service in those campaigns during World War II. Many letters to Sledge commenting on With the Old Breed contain wartime reminiscences of soldiers who also served in the Pacific in World War II. The collection includes photographs including World War II era photos of his platoon, contemporary photographs of Peleliu and Okinawa, and photographs of veterans’ groups. It also contains articles by Sledge and other authors concerning World War II in the Pacific, clippings relating to the 50th anniversary of World War II, correspondence (including wartime correspondence), and artifacts. Biographical / Historical Sketch: Eugene B. Sledge was born November 4, 1923, in Mobile, Alabama, son of Edward S. and Mary Frank Sturdivant Sledge. He volunteered for the Marine Corps in 1942 during World War II, and after a brief stay in an officer training program at Georgia Tech, enlisted and fought with the Marine Corps in the Pacific theater of the war, participating in the battles of Peleliu and Okinawa in 1944 and 1945. He spent some time with the Marine Corps in Beijing, China after the war, before being discharged from service in 1946.