Jute Workers' Strikes in Titagarh in the Late 1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Population Growth in the Municipalities of North 24 Parganas, It Is Clear That North 24 Parganas Has Retained a High Level of Urbanization Since Independence

World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development WWJMRD 2018; 4(3): 68-73 www.wwjmrd.com International Journal Peer Reviewed Journal Urban Population Growth in the Municipalities of Refereed Journal Indexed Journal North 24 Parganas: A Spatio-Temporal Analysis UGC Approved Journal Impact Factor MJIF: 4.25 E-ISSN: 2454-6615 Mashihur Rahaman Mashihur Rahaman Abstract Research Scholar The rapid growth of urban population causes various problems in urban centres like increased P.G. Department of unemployment, economic instability, lacks of urban facilities, unhygienic environmental conditions Geography, Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar, etc. People were well aware about the importance of population studies from very beginning. Odisha, India Explosively growing of urban population has attracted the attention of urban geographers and town planners. For country like India, it is very important to study the decadal variation of population growth, it helps in realizing problems. The population growth and socio-economic changes are closely related to each other. In present study North 24 Parana’s has been chosen as study area. The level of urbanization remained high in the district (57.6 % in 2011). Rapid increase in urbanization can be attributed to growth of Kolkata metropolis.Barasat is now within greater Kolkata (Kolkata 124).From 1991 onwards the real estate business in this district thrived and projects were taken which are more of residential type than business type. The aim of the present paper is to investigate the change in urban population growth rate of municipality wise during the three decades 1981-91, 1991- 2001 and 2001-2011. Due to push-pull factors the rural-urban migration is causing the process of urbanization. -

Government of West Bengal Office of the Sub-Divisional Magistrate & Sub-Divisional Officer, Barrackpore, North 24 Parganas P

Government of West Bengal Office of the Sub-Divisional Magistrate & Sub-Divisional Officer, Barrackpore, North 24 Parganas Phone-033 2592 0616; Fax-033 2592 0814 e-mail: [email protected] ORDER In partial modification of this office Memo No. 167(9)/ConlBkp dated 04.02.2021 in connection with ensuing West Bengal Legislative Assembly General Election, 2021 the following officers are drafted as Assistant Returning Officer under 103 — Bizpur Assembly Constituency to 114-Dum Dum Assembly Constituency (copy enclosed). Sub-Divisional Magistrate & Sub-Divisional Officer Barrackpore, North 24 Parganas Memo No. /ConfBkp Date 20.02.2021 Copy forwarded for information to:- 1. The District Magistrate & District Election Officer, North 24 Parganas, Barasat 2. The Commissioner of Police, Barrackpore Police Commissionerate, Barrackpore 3. The Additional District Magistrate (General), North 24 Parganas, Barasat 4. The Returning Officer, Assembly Constituency 5. The Officer-in-Charge, Election, Barrackpore 6. The Officer-in-Charge, Training Cell, Barrackpore 7. The N.D.C., Barrackpore 8. The (Head of the Office) 9. Sri / Smt. , Assistant Returning Officer, Assembly Constituency Sub-Divisional Magistrate & Sub-Divisional Officer Barrackpore, North 24 Parganas List of AROs in connection with General Election to WBLA, 2021 AC No. & SI. Name of ARO Name No. Designation of ARO Mobile No. Senior Revenue Officer - II & Block Land & Land I AtanuDas 9903211705 Reforms Officer, Barrackpore - I Revenue Officer (1), Block Land & Land Reforms 2 SanjoyKumarDas 8582843535 Officer's Office, Barrackpore - 103 - Bijpur Revenue Officer (II), Block Land & Land Reforms 3 Subhashia Dasgupta 9851088820 Officer's Office, Barrackpore - 4 Santu Das C.D.P.O., ICDS, Kanchrapara 8927802757 8240454775 / 5 Sekh Kabir Ali Sub - Inspector of Schools, Bizpur Circle 8768788652 8336959188 I 1 Samit Sarkar, WBCS (Exe.) B.D.O., Barrackpore-1 7439311972 2 Gour Chandra Mandal 104 - Naihati it. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

AS, Total Pages: 48 State Nodal Officer, NUHM

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT NATIONAL HEALTH MISSION (NHM) GN -29, 1ST FLOOR, GRANTHAGAR BHAWAN, SWASTHYA BHAWAN PREMISES,SECTOR-V SALT LAKE, BIDHANNAGAR, KOLKATA - 700091. ~ 033 - 2357 - 7928, A 033 - 2357 - 7930, Email ID: [email protected]; website: www.wbhealth.gov.in Memo No. HFW INUHM-887 /2016/2 , C) 0 Date: Jq .4.2018 From : State Nodal Officer, NUHM Government of West Bengal To : Managing Director, Basumati Corporation Ltd. (A Government of West Bengal Undertaking) Sub: Work order for supplying "Induction Training Module of MAS under NUHM" Sir, Apropos the captioned subject, I am to inform you that your firm has been selected for supplying the materials to the CMOH office of the districts and ULB office as per the following table: Printing Quantity Specification Rate including Materials delivery charges +GST (In Rs) Induction Training 150000 copies Size: AS, Total Pages: 48 Rs.12.38 per book Module of MAS Paper: Inside 130 GSM Art paper & +Rs. 1.48 (12% under NUHM- A Cover 200 GSM GST) Handbook Printing: Multi Colour allover Binding: Side stitch with perfect binding Packing: Kraft paper/plastic Packet packing The detail list of consignees with quantity to be supplied has been annexed in Annexure A(Name of the Districts & SPMU) & Annexure B (Name of the ULBs). Prior to printing, the proof of the matter has to be approved by the State Programme Management Unit, NUHM. The entire supply will have to be delivered at the districts and ULBs within 30(Thirty) days from the issuance of this letter. The receipt of delivery should submit at the time of payment. -

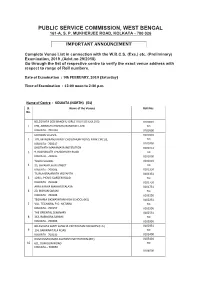

Complete Names and Addresses of the Venues of the Upcoming West

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 026 IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT Complete Venue List in connection with the W.B.C.S. (Exe.) etc. (Preliminary) Examination, 2019 ,(Advt.no 29/2018) Go through the list of respective centre to verify the exact venue address with respect to range of Roll numbers. Date of Examination : 9th FEBRUARY, 2019 (Saturday) Time of Examination : 12:00 noon to 2:30 p.m. Name of Centre : KOLKATA (NORTH) (01) Sl. Name of the Venues Roll Nos. No. BELEGHATA DESHBANDHU GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL (HS) 0100001 1 69B, ABINASH CHANDRA BANERJEE LANE TO KOLKATA - 700 010 0100500 MODERN SCHOOL 0100501 2 17B, MANORANJAN ROY CHOUDHURY ROAD, PARK CIRCUS, TO KOLKATA - 700017 0100750 BHUTNATH MAHAMAYA INSTITUTION 0100751 3 9, RADHANATH CHOWDHURY ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700015 0101000 TOWN SCHOOL 0101001 4 33, SHYAMPUKUR STREET TO KOLKATA - 700004 0101350 TILJALA BRAJANATH VIDYAPITH 0101351 5 129/1, PICNIC GARDEN ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700039 0101750 ARYA KANYA MAHAVIDYALAYA 0101751 6 20, BIDHAN SARANI TO KOLKATA - 700006 0102250 TEGHARIA SIKSHAYATAN HIGH SCHOOL (HS) 0102251 7 VILL. TEGHARIA, P.O. HATIARA TO KOLKATA - 700157 0102550 THE ORIENTAL SEMINARY 0102551 8 363, RABINDRA SARANI TO KOLKATA - 700006 0102950 BELEGHATA SANTI SANGHA VIDYAYATAN FOR BOYS (H.S.) 0102951 9 1/4, BARWARITALA ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700010 0103400 DUM DUM KUMAR ASUTOSH INSTITUTIOIN (BR.) 0103401 10 6/1, DUM DUM ROAD TO KOLKATA – 700030 0104000 KHANNA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0104001 11 9, SHIVKUMAR KHANNA SARANI TO KOLKATA – 700015 0104350 KHANNA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'B'; 0104351 12 9, SHIVKUMAR KHANNA SARANI TO KOLKATA - 700015 0104700 BELEGHATA SANTI SANGHA VIDYAYATAN FOR GIRLS 0104701 13 1/8, BAROWARITALA ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700010 0105250 BELEGHATA DESHBANDHU HIGH SCHOOL (BR.) 0105251 14 17/2E, BELEGHATA MAIN ROAD TO KOLKATA – 700010 0105700 BAGMARI MANIKTALA GOVT. -

COVID Session Sites North 24 Parganas 10.3.21

COVID Session Sites North 24 Parganas 10.3.21 Sl No District /Block/ ULB/ Hospital Session Site name Address Functional Status Ashoknagar Kalyangarh 1 Ashoknagar SGH Govt. Functional Municipality 2 Bangaon Municipality Bongaon SDH & SSH Govt. Functional 3 Baranagar Municipality Baranagar SGH Govt. Functional 4 Barasat Municipality Barasat DH Govt. Functional 5 Barrackpur - I Barrackpore SDH Govt. Functional 6 Bhatpara Municipality Bhatpara SGH Govt. Functional Bidhannagar Municipal 7 Salt Lake SDH Govt. Functional Corporation 8 Habra Municipality Habra SGH Govt. Functional 9 Kamarhati Municipality Session 1 Academic Building Govt. Functional Session 2 Academic Building, Sagar Dutta Medical college 10 Kamarhati Municipality Govt. Functional and hospital 11 Kamarhati Municipality Session 3 Lecture Theater Govt. Functional 12 Kamarhati Municipality Session 4 Physiology Dept Govt. Functional 13 Kamarhati Municipality Session 5 Central Library Govt. Functional 14 Kamarhati Municipality Collage of Medicine & Sagore Dutta MCH Govt. Functional 15 Khardaha Municipality Balaram SGH Govt. Functional 16 Naihati Municipality Naihati SGH Govt. Functional 17 Panihati Municipality Panihati SGH Govt. Functional 18 Amdanga Amdanga RH Govt. Functional 19 Bagda Bagdah RH Govt. Functional 20 Barasat - I Chhotojagulia BPHC Govt. Functional 21 Barasat - II Madhyamgram RH Govt. Functional 22 Barrackpur - I Nanna RH Govt. Functional 23 Barrackpur - II Bandipur BPHC Govt. Functional 24 Bongaon Sundarpur BPHC Govt. Functional 25 Deganga Biswanathpur RH Govt. Functional 26 Gaighata Chandpara RH Govt. Functional 27 Habra - I Maslandpur RH Govt. Functional 28 Habra - II Sabdalpur RH Govt. Functional 29 Rajarhat Rekjoani RH Govt. Functional 30 Amdanga Adhata PHC Govt. Functional 31 Amdanga Beraberia PHC Govt. Functional 32 Amdanga Maricha PHC Govt. Functional 33 Bagda Koniara PHC Govt. -

HFW-27038/17/2019-NHM SEC-Dept.Of H&FW/3641

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL HEALTH & FAMILYWELFAREDEPARTMENT NATIONALHEALTHMISSION(NHM) GN-29, 2ndFLOOR,GRANTHAGARBHAWAN, SWASTHYABHAWANPREMISES,SECTOR-V - SALTLAKE,BIDHANNAGAR,KOLKATA- 700 091. NATIONAL URBAN HEALTH MISSION ~ 033 - 2333-0432, !Ali 033 - 2357 - 7930, e-Mail 10: [email protected]; website: www.wbhealth.gov.in Memo No. HFW-27038/17/2019-NHM SEC-Dept.of H&FW/ l_Glt1 Date: 11/11/2019 From : Additional Mission Director, NHM & Joint Secretary, Government of West Bengal To Chief Medical Officer of Health, (Howrah / North 24 Parganas / Basirhat HD) Sub: Meeting on Infrastructure strengthening works under NUHM Madam / Sir, A meeting will be held on 19th November, 2019 from 11.00 A.M.at Muktodhara, 5th Floor, Meeting Hall, Swasthya Sathi Building, Swasthya Bhawan, Kolkata - 700 091 to review the infrastructure strengthening works and utilisation offund under NUHMin different ULBsunder your district. Agenda of the review meeting are as follows- 1. Construction of new U-PHCbuildings 2. Procurement and installation of lab-equipments 3. Financial review The following officials of your district and ULBs as mentioned below may please be requested to make it convenient to attend the meeting. Level Participants 1. Consultant Epidemiologist, NUHM / District Programme Coordinator, NHM, DPMU (in absence of Consultant Epidemiologist, NUHM, District Programme Coordinator, NHMmay be allowed to participate) 2. Assistant Engineer / Sub-Assistant Engineer, NHM, DPMU (in absence of District Assistant Engineer, NHM, Sub-Assistant Engineer, NHM may be allowed to participate) 3. Accounts Manager, NUHM / District Accounts Manager, NHM, DPMU (in absence of Accounts Manager, NUHM,District Accounts Manager, NHM may be allowed to participate) 1. Nodal Officer, NUHM(Municipal Corporation / Municipality) 2. -

Titagarh Municipality 1, B.T

TITAGARH MUNICIPALITY 1, B.T. Road, Titagarh, North 24-Parganas, Kolkata -700119. EMPLOYMENT NOTICE For details visit our website: www.titagarhmunicipality.in & wwrv.sudawb.org and Notice Sd/- Chairperson Dated: 08.02.2021. Titagarh Municipality 'B:ard of Administrators of Titagarh Municipality * .- c -J-- (g !a <_""r c- - , - --- -' -_- l<:s ,l ] b;z' I Ali \lembers of Board of Administraton of Titrgmh \,[unici0ilitv : The Director, suDA, ILGUS ghavan.Hi ato*a_s**.-=.1\i,\-s*=*=.E"_,,\u\\arar\D-rDb. ---\]r.-D^r=_,irctMaqisttate,sfo<l,f -<Vo.go",==. The I S.D.O., Banackpore,North Z+ eiguna*. 6 ' \\\\\e\$\ers s\ Se\ect\on commrttee tor engagement of Health officer of Titagarh Municipality 1 ' The lr co-ordinator, Titagarh Municipality-- with tr." Jir""tio', to make-neces*ry urrurg"ment, 8 Notice Board, Titagarh Municipality as discussed. 9. Guard File Prn Chairperson, Titagarh Municipality & Chairman of Selection Committee for engagement of Health Officer of Titagarh Municipality s ,,"0mffiroalrr 31s1a6.OrJ.t'i1!i Phone No.2501-0359 E-Mail r. n. titagad;ffi ffiii,L];lJtr OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF ADMINTSTRATORS OF TITAGARH MUNICIPALITY 1. B.T. Road. Titagarh. North 24-Parganas. Kolkata - 700119. EMPLOVMENT NOTICE No. Recruitment/TW2}2l I I Dated: 08.02.2021. In terms of the letter No.SUDA-ll0l7(18)/l/202015608 dated O4.ll.2O2O of Director, SUDA issued in light of Notification No.925IMA/O/C-9/2A-712015 dated 02.11.2020 of the Joint Secretary to the GoW. of West Bengal, ttD&MA Deptt., Nagarayan, applications are invited on line at the website of Titagarh Municipality (www.titagar.hmunicipality.in) & at the website of Urban Development & Municipal Affairs Department ( t^i hJ to . -

Affected Zone Wise Division of Containment Zones in North 24 Parganas

Affected Zone wise Division of Containment Zones in North 24 Parganas SL No Muni/Block Ward/GP Affected Zone Police Station 1 BSF Camp, Alambazar Baranagar 4 2 Kumarpara Lane,Jhilbagan, Kol-35 Baranagar 3 8 Deshbandhu Road(West) Baranagar 4 13 Gopal Lal Thakur Road, Baranagar Baranagar 5 14 Banhoogly , Rabindranagar Baranagar 6 17 Nabin Chandra Das Road, Sreepalli Baranagar 7 18 A K Mukherjee Road Baranagar A. K Mukherjee Rd 8Baranagar 19 Baranagar Baranagar, Subhas Nagar, Noa para 9 21 Bir Anantaram Mondal Lane Baranagar 10 25 Jogendra Basak Road, Baranagar Baranagar 11 26 Jogendra Basak Road, Baranagar Baranagar 12 27 Ramchand Mukherjee Lane Baranagar 13 32 MNK Road (S) Baranagar 14 33 JN Banerjee lane Baranagar 15 34 B.K. Maitra Road Baranagar 15 Kazipara Barasat 16 Barasat 17 31 Hridaypur Barasat 18 5 Sadhu Mukherjee Road. Titagarh Sumagalpur Old Calcutta Road, Barrackpore, 19 10 Titagarh Barrackpore Talpukur 20 19 Gandhi more near Mother Teresa Hospital Titagarh 21 23 N.N.BAGCHI RD Titagarh Anandaprasad Banerjee Road, Rathtala, 22 7 Katadanga, South A B Road, Singapara, Bhatpara Bhatpara 23 12 Kelabagan Bakar Mahalla, Bhatpara Bhatpara 24 Bhatpara 13 KANKINARA Bhatpara 25 17 Puranitala, Jagaddal Jagaddal 26 19 Rajpukurpath, Authpur, Jagaddal Jagaddal 27 27 Gurdaha natun pally, Shyamnagar Bhatpara 28 33 UTTAR PANPUR, BHATPARA, JAGADDAL Bhatpara Apollo Nursing Home/ Hostel, Gopalpur, Bat- 29 3 Narayanpur tala, Narayanpur Rajarhat, Nutanpara, Pragati Sangha, PO 30 4 Narayanpur Dhapa NISHIKANAN,TEGHARIA,DHALIPARA, 6 (part) CHARNOCK HOSTEL, -

Municipal General Election, 2015 (List of Winning Candidates) Name of the Municipality : Titagarh

Municipal General Election, 2015 (List of Winning Candidates) Name of the Municipality : Titagarh Name of Ward Name of Winning Sl.No. Address Party Affiliation CONTACT NO. REMARKS Municipality No. Candidate 23/A, PARK ROAD, P.O.- & P.S.-TITAGARH, DIST-NORTH 24 COMMUNIST PARTY OF 1 Titagarh 1 ARUN KUMAR SINGH 9331846645 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700119 INDIA (MARXIST) 26 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA PATH,PO&PS:TITAGARH,DIST- ALL INDIA TRINAMUL 2 Titagarh 2 SUSHMITA YADAV 8583084547 24PGS(N),KOLKATA-700119 CONGRESS K.J.M. LINE NO.-14/15, S. V. PATH, P.O. & P.S.-TITAGARH, ALL INDIA TRINAMUL 3 Titagarh 3 OMPRAKASH GOND 9831303154 DIST-NORTH 24 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700119 CONGRESS 9/11 S.S. PATH, BANSBAGAN, P.O.-+P.S-TITAGARH, NORTH 24 ALL INDIA TRINAMUL 4 Titagarh 4 ASHA SHARMA 8100177586 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700119 CONGRESS S. M. SIDING, BOWBAZAR, P.O& P.S- TITAGARH, DIST- NORTH ALL INDIA TRINAMUL 5 Titagarh 5 SUNITA CHOWDHARY 8961202094 24 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700119 CONGRESS 2 NO RAMKRISHNA DEO PATH, TITAGARH, NORTH 24 ALL INDIA TRINAMUL 6 Titagarh 6 ATINDRA KUMAR SHAW 9007084046 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700119(NEAR STANDARD NEW LINE) CONGRESS 33, B.T.ROAD, HOUSE OF MAHANANDA SINGH, MUCHI 7 Titagarh 7 MANISH SHUKLA PARA, P.O.-TALPUKUR, P.S.-TITAGARH, DIST-NORTH 24 IND 9330918786 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700123 2NO M G ROAD, PAPER MILL MORE, P.O & P.S- TITAGARH, ALL INDIA TRINAMUL 8 Titagarh 8 OM PRAKASH SHAW 9831244628 NORTH 24 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700119 CONGRESS A.N.DEO ROAD, PURANI BAZAR, WARD NO.-10, P.O. & P.S.- INDIAN NATIONAL 9 Titagarh 9 NIRMALA DEVI SHAW 9748370310 TITAGARH, DIST-NORTH 24 PARGANAS, KOLKATA-700119 CONGRESS TITAGARH NO 1 JUTEMILL LINE, ROOM NO 393, M. -

Jagatdal Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-106-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-677-9 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 150 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town, Ward & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-13 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns, Ward and Villages 14-16 by Population Size | -

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/Husband Middle Name Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP.ID-CL.ID. Account No. Invest Type Amount Transferred Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF PAN Number Aadhar Number 74/153 GANDHI NAGAR A ARULMOZHI NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 636102 IN301774-10480786-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 160.00 15-Sep-2019 ATTUR 1/26, VALLAL SEETHAKATHI SALAI A CHELLAPPA NA KILAKARAI (PO), INDIA Tamil Nadu 623517 12010900-00960311-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 60.00 15-Sep-2019 RAMANATHAPURAM KILAKARAI OLD NO E 109 NEW NO D A IRUDAYAM NA 6 DALMIA COLONY INDIA Tamil Nadu 621651 IN301637-40636357-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 KALAKUDI VIA LALGUDI OPP ANANDA PRINTERS I A J RAMACHANDRA JAYARAMACHAR STAGE DEVRAJ URS INDIA Karnataka 577201 IN300360-10245686-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 8.00 15-Sep-2019 ACNPR4902M NAGAR SHIMOGA NEW NO.12 3RD CROSS STREET VADIVEL NAGAR A J VIJAYAKUMAR NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 632001 12010600-01683966-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 100.00 15-Sep-2019 SANKARAN PALAYAM VELLORE THIRUMANGALAM A M NIZAR NA OZHUKUPARAKKAL P O INDIA Kerala 691533 12023900-00295421-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 AYUR AYUR FLAT - 503 SAI DATTA A MALLIKARJUNAPPA ANAGABHUSHANAPPA TOWERS RAMNAGAR INDIA Andhra Pradesh 515001 IN302863-10200863-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 80.00 15-Sep-2019 AGYPA3274E