Failure of Hydrostatic Equilibrium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydrostatic Shapes

7 Hydrostatic shapes It is primarily the interplay between gravity and contact forces that shapes the macroscopic world around us. The seas, the air, planets and stars all owe their shape to gravity, and even our own bodies bear witness to the strength of gravity at the surface of our massive planet. What physics principles determine the shape of the surface of the sea? The sea is obviously horizontal at short distances, but bends below the horizon at larger distances following the planet’s curvature. The Earth as a whole is spherical and so is the sea, but that is only the first approximation. The Moon’s gravity tugs at the water in the seas and raises tides, and even the massive Earth itself is flattened by the centrifugal forces of its own rotation. Disregarding surface tension, the simple answer is that in hydrostatic equi- librium with gravity, an interface between two fluids of different densities, for example the sea and the atmosphere, must coincide with a surface of constant ¡A potential, an equipotential surface. Otherwise, if an interface crosses an equipo- ¡ A ¡ A tential surface, there will arise a tangential component of gravity which can only ¡ ©¼AAA be balanced by shear contact forces that a fluid at rest is unable to supply. An ¡ AAA ¡ g AUA iceberg rising out of the sea does not obey this principle because it is solid, not ¡ ? A fluid. But if you try to build a little local “waterberg”, it quickly subsides back into the sea again, conforming to an equipotential surface. Hydrostatic balance in a gravitational field also implies that surfaces of con- A triangular “waterberg” in the sea. -

Astronomy 201 Review 2 Answers What Is Hydrostatic Equilibrium? How Does Hydrostatic Equilibrium Maintain the Su

Astronomy 201 Review 2 Answers What is hydrostatic equilibrium? How does hydrostatic equilibrium maintain the Sun©s stable size? Hydrostatic equilibrium, also known as gravitational equilibrium, describes a balance between gravity and pressure. Gravity works to contract while pressure works to expand. Hydrostatic equilibrium is the state where the force of gravity pulling inward is balanced by pressure pushing outward. In the core of the Sun, hydrogen is being fused into helium via nuclear fusion. This creates a large amount of energy flowing from the core which effectively creates an outward-pushing pressure. Gravity, on the other hand, is working to contract the Sun towards its center. The outward pressure of hot gas is balanced by the inward force of gravity, and not just in the core, but at every point within the Sun. What is the Sun composed of? Explain how the Sun formed from a cloud of gas. Why wasn©t the contracting cloud of gas in hydrostatic equilibrium until fusion began? The Sun is primarily composed of hydrogen (70%) and helium (28%) with the remaining mass in the form of heavier elements (2%). The Sun was formed from a collapsing cloud of interstellar gas. Gravity contracted the cloud of gas and in doing so the interior temperature of the cloud increased because the contraction converted gravitational potential energy into thermal energy (contraction leads to heating). The cloud of gas was not in hydrostatic equilibrium because although the contraction produced heat, it did not produce enough heat (pressure) to counter the gravitational collapse and the cloud continued to collapse. -

STARS in HYDROSTATIC EQUILIBRIUM Gravitational Energy

STARS IN HYDROSTATIC EQUILIBRIUM Gravitational energy and hydrostatic equilibrium We shall consider stars in a hydrostatic equilibrium, but not necessarily in a thermal equilibrium. Let us define some terms: U = kinetic, or in general internal energy density [ erg cm −3], (eql.1a) U u ≡ erg g −1 , (eql.1b) ρ R M 2 Eth ≡ U4πr dr = u dMr = thermal energy of a star, [erg], (eql.1c) Z Z 0 0 M GM dM Ω= − r r = gravitational energy of a star, [erg], (eql.1d) Z r 0 Etot = Eth +Ω = total energy of a star , [erg] . (eql.1e) We shall use the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium dP GM = − r ρ, (eql.2) dr r and the relation between the mass and radius dM r =4πr2ρ, (eql.3) dr to find a relations between thermal and gravitational energy of a star. As we shall be changing variables many times we shall adopt a convention of using ”c” as a symbol of a stellar center and the lower limit of an integral, and ”s” as a symbol of a stellar surface and the upper limit of an integral. We shall be transforming an integral formula (eql.1d) so, as to relate it to (eql.1c) : s s s GM dM GM GM ρ Ω= − r r = − r 4πr2ρdr = − r 4πr3dr = (eql.4) Z r Z r Z r2 c c c s s s dP s 4πr3dr = 4πr3dP =4πr3P − 12πr2P dr = Z dr Z c Z c c c s −3 P 4πr2dr =Ω. Z c Our final result: gravitational energy of a star in a hydrostatic equilibrium is equal to three times the integral of pressure within the star over its entire volume. -

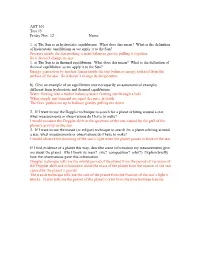

1. A) the Sun Is in Hydrostatic Equilibrium. What Does

AST 301 Test #3 Friday Nov. 12 Name:___________________________________ 1. a) The Sun is in hydrostatic equilibrium. What does this mean? What is the definition of hydrostatic equilibrium as we apply it to the Sun? Pressure inside the star pushing it apart balances gravity pulling it together. So it doesn’t change its size. 1. a) The Sun is in thermal equilibrium. What does this mean? What is the definition of thermal equilibrium as we apply it to the Sun? Energy generation by nuclear fusion inside the star balances energy radiated from the surface of the star. So it doesn’t change its temperature. b) Give an example of an equilibrium (not necessarily an astronomical example) different from hydrostatic and thermal equilibrium. Water flowing into a bucket balances water flowing out through a hole. When supply and demand are equal the price is stable. The floor pushes me up to balance gravity pulling me down. 2. If I want to use the Doppler technique to search for a planet orbiting around a star, what measurements or observations do I have to make? I would measure the Doppler shift in the spectrum of the star caused by the pull of the planet’s gravity on the star. 2. If I want to use the transit (or eclipse) technique to search for a planet orbiting around a star, what measurements or observations do I have to make? I would observe the dimming of the star’s light when the planet passes in front of the star. If I find evidence of a planet this way, describe some information my measurements give me about the planet. -

Astronomy 241: Review Questions #1 Distributed: September 20, 2012 Review the Questions Below, and Be Prepared to Discuss Them I

Astronomy 241: Review Questions #1 Distributed: September 20, 2012 Review the questions below, and be prepared to discuss them in class on Sep. 25. Modified versions of some of these questions will be used in the midterm exam on Sep. 27. 1. State Kepler’s three laws, and give an example of how each is used. 2. You are in a rocket in a circular low Earth orbit (orbital radius aleo =6600km).Whatve- 1 locity change ∆v do you need to escape Earth’s gravity with a final velocity v =2.8kms− ? ∞ Assume your rocket delivers a brief burst of thrust, and ignore the gravity of the Moon or other solar system objects. 3. Consider a airless, rapidly-spinning planet whose axis of rotation is perpendicular to the plane of its orbit around the Sun. How will the local equilibrium surface temperature temperature T depend on latitude ! (measured, as always, in degrees from the planet’s equator)? You may neglect heat conduction and internal heat sources. 3 4. Given that the density of seawater is 1025 kg m− ,howdeepdoyouneedtodivebefore the total pressure (ocean plus atmosphere) is 2P0,wherethetypicalpressureattheEarth’s 5 1 2 surface is P =1.013 10 kg m− s− ? 0 × 5. An asteroid of mass m M approaches the Earth on a hyperbolic trajectory as shown " E in Fig. 1. This figure also defines the initial velocity v0 and “impact parameter” b.Ignore the gravity of the Moon or other solar system objects. (a) What are the energy E and angular momentum L of this orbit? (Hint: one is easily evaluated when the asteroid is far away, the other when it makes its closest approach.) (b) Find the orbital eccentricity e in terms of ME, E, L,andm (note that e>1). -

News & Views Research

RESEARCH NEWS & VIEWS measure the dwarf planet’s size, shape and density more accurately than ever before. Compared with other bodies in the Solar System, Haumea rotates quickly (making one rotation in about four hours), and is strangely shaped, like an elongated egg. Ortiz et al. calculate that the object’s longest axis is at least 2,300 km, which is larger than earlier estimates6–8. In turn, given known values for Haumea’s mass and brightness, the dwarf planet’s density and reflectivity are both lower CSI DE ANDALUCIA DE ASTROFISICA INSTITUTO than the unusually high values previously considered. The authors’ results suggest that Haumea might not be in hydrostatic equilibrium, and this touches on the still-sensitive topic of how planets and dwarf planets should be defined. Remarkably, the authors show that blinks in the starlight, detected at multiple observa- tion sites both before and after a distant star was blocked by Haumea, are consistent with a 70-km-wide ring of material encircling the body, approximately 1,000 km away from Haumea’s surface (Fig. 1). Saturn’s are the most studied of all rings, Figure 1 | Artist’s impression of Haumea and its ring. Ortiz et al.4 have measured the size, shape and and yet they remain enigmatic. Data from the density of the dwarf planet Haumea with unprecedented accuracy and found that it has a planetary ring. Cassini spacecraft revealed that gravitational This is the first time that a ring has been discovered around a distant body in the Solar System. interactions between the planet’s rings and moons shepherd the ring material, and that Ring systems represent microcosms of the transition from the outer Solar System, one of the rings is produced entirely from larger-scale rotating structures, such as including close encounters with the giant matter that spews from the moon Encela- galaxies and proto-planetary disks — the disks planets14. -

How Stars Work: • Basic Principles of Stellar Structure • Energy Production • the H-R Diagram

Ay 122 - Fall 2004 - Lecture 7 How Stars Work: • Basic Principles of Stellar Structure • Energy Production • The H-R Diagram (Many slides today c/o P. Armitage) The Basic Principles: • Hydrostatic equilibrium: thermal pressure vs. gravity – Basics of stellar structure • Energy conservation: dEprod / dt = L – Possible energy sources and characteristic timescales – Thermonuclear reactions • Energy transfer: from core to surface – Radiative or convective – The role of opacity The H-R Diagram: a basic framework for stellar physics and evolution – The Main Sequence and other branches – Scaling laws for stars Hydrostatic Equilibrium: Stars as Self-Regulating Systems • Energy is generated in the star's hot core, then carried outward to the cooler surface. • Inside a star, the inward force of gravity is balanced by the outward force of pressure. • The star is stabilized (i.e., nuclear reactions are kept under control) by a pressure-temperature thermostat. Self-Regulation in Stars Suppose the fusion rate increases slightly. Then, • Temperature increases. (2) Pressure increases. (3) Core expands. (4) Density and temperature decrease. (5) Fusion rate decreases. So there's a feedback mechanism which prevents the fusion rate from skyrocketing upward. We can reverse this argument as well … Now suppose that there was no source of energy in stars (e.g., no nuclear reactions) Core Collapse in a Self-Gravitating System • Suppose that there was no energy generation in the core. The pressure would still be high, so the core would be hotter than the envelope. • Energy would escape (via radiation, convection…) and so the core would shrink a bit under the gravity • That would make it even hotter, and then even more energy would escape; and so on, in a feedback loop Ë Core collapse! Unless an energy source is present to compensate for the escaping energy. -

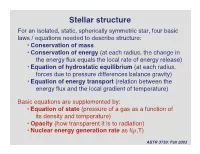

Stellar Structure

Stellar structure For an isolated, static, spherically symmetric star, four basic laws / equations needed to describe structure: • Conservation of mass • Conservation of energy (at each radius, the change in the energy flux equals the local rate of energy release) • Equation of hydrostatic equilibrium (at each radius, forces due to pressure differences balance gravity) • Equation of energy transport (relation between the energy flux and the local gradient of temperature) Basic equations are supplemented by: • Equation of state (pressure of a gas as a function of its density and temperature) • Opacity (how transparent it is to radiation) • Nuclear energy generation rate as f(r,T) ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Conservation of mass Let r be the distance from the center Density as function of radius is r(r) dr r m dm Let m be the mass interior to r, then r conservation of mass implies that: R 2 M dm = 4pr rdr Write this as a differential equation: dm st † = 4pr 2r 1 stellar structure dr equation † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Equation of hydrostatic equilibrium P(r+dr) Consider small cylindrical r+dr element between radius r and radius r + dr in the star. Surface area = dS r Mass = Dm P(r) Mass of gas in the star at smaller gravity radii = m = m(r) Radial forces acting on the element: GmDm Gravity (inward): F = - g r2 gravitational constant G = 6.67 x 10-8 dyne cm2 g-2 † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Pressure (net force due to difference in pressure between upper and lower faces): Fp = P(r)dS - P(r + dr)dS È dP ˘ = P(r)dS - P(r) + ¥ dr dS ÎÍ dr ˚˙ dP = - drdS dr Mass -

Efficient Early Global Relaxation of Asteroid Vesta

Efficient early global relaxation of asteroid Vesta R. R. Fu, B. H. Hager, A. I. Ermakov, and M. T. Zuber Abstract The asteroid Vesta is a differentiated planetesimal from the accretion phase of solar sys- tem formation. Although its present-day shape is dominated by a non-hydrostatic fossil equatorial bulge and two large, mostly unrelaxed impact basins, Vesta may have been able to approach hydrostatic equilibrium during a brief early period of intense interior heating. We use a finite element viscoplastic flow model coupled to a 1D conductive cooling model to calculate the expected rate of relaxation throughout Vesta’s early his- tory. We find that, given sufficient non-hydrostaticity, the early elastic lithosphere of Vesta experienced extensive brittle failure due to self-gravity, thereby allowing relax- ation to a more hydrostatic figure. Soon after its accretion, Vesta reached a closely hydrostatic figure with <2 km non-hydrostatic topography at degree-2, which, once scaled, is similar to the maximum disequilibrium of the hydrostatic asteroid Ceres. Vesta was able to support the modern observed amplitude of non-hydrostatic topogra- phy only >40-200 My after formation, depending on the assumed depth of megaregolith. The Veneneia and Rheasilvia giant impacts, which generated most non-hydrostatic to- pography, must have therefore occurred >40-200 My after formation. Based on crater retention ages, topography, and relation to known impact generated features, we iden- tify a large region in the northern hemisphere that likely represents relic hydrostatic terrain from early Vesta. The long-wavelength figure of this terrain suggests that, be- fore the two late giant impacts, Vesta had a rotation period of 5.02 hr (6.3% faster than present) while its spin axis was offset by 3.0◦ from that of the present. -

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) Is the Organization That Determines the Official Names and Classifications for All Celestial Bodies

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) is the organization that determines the official names and classifications for all celestial bodies. Prior to the IAU meeting on August 24, 2006, there had not been a singular definition created for planets. It was widely thought that our solar system consisted of nine planets, which ended with Pluto. After the discovery of another large object far beyond Pluto (later named Eris), there was an argument whether the new discovery should also be called a planet. Prior to the discovery of Eris, the general consensus was that a planet (with the exception of asteroids and comets) is a celestial body that is round and revolves around the Sun. Thus, the IAU now needed to discuss what characteristics define a planet. After heated debates among its members, the IAU agreed that the patterns in which objects in our solar system revolve around the Sun, as well as the orbits of the objects, help determine how these objects are classified. Furthermore, the IAU redefined a planet as a celestial body that meets three requirements: (1) it orbits the Sun, (2) it has enough mass to overcome forces to reach hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (3) it dominates the area around its orbit (IAU 2006). Pluto met the first two requirements, but since t the orbit is crowded with other objects and is not massive enough to clear other objects away, it did not meet the third criteria. The IAU decided on the term “dwarf planet” when the object fits the first two criteria, but not the third. -

LESSON PLAN Teacher: Date: Prior to “Give Me Space!” Performance

LESSON PLAN Teacher: Date: Prior to “Give Me Space!” performance Grade Level/Subject: 4th/Math & Science Co-Teaching Model Utilized: Central Focus: To only serve as a predecessor classroom activity accompaniment for students meant to experience the performance of “GIVE ME SPACE!” During the performance, all students will intentionally hear musical compositions written for each of the 5 – IAU established dwarf planets and acknowledge as fourth graders their previously conducted study where constructing 3-D volumetric scaled models indicate their relative sizes to one another, positioning locations in- and outside of our solar system, while also learning of their reasons of qualification as dwarf status and then additional physical properties. Standards: Math 4.NF.B.3. Understand a fraction a/b with a>1 as a sum of fractions 1/b. 4.NF.B.4. Apply and extend previous understandings of multiplication as repeated addition to multiply a whole number by a fraction. 4.NF.B.5. Express a fraction with denominator 10 as an equivalent fraction with denominator 100, and use this technique to add two fractions with respective denominators 10 and 100. 4.MD.A.1. Measure and estimate to determine relative sizes of measurement units within a single system of measurement involving length, liquid volume, and mass/weight of objected using customary and metric units. 4.MD.B.4 Make a line plot to display a data set of measurements in fractions of a unit. Use operations on fractions for this grade to solve problems involving information presented in line plots. Science 4.ETS2:1) Use appropriate tools and measurements to build a model. -

Lecture 4 Hydrostatics and Time Scales

Assumptions – most of the time • Spherical symmetry Broken by e.g., convection, rotation, magnetic fields, explosion, instabilities Makes equations a lot easier. Also facilitates Lecture 4 the use of Lagrangian (mass shell) coordinates Hydrostatics and Time Scales • Homogeneous composition at birth • Isolation frequently assumed Glatzmaier and Krumholz 3 and 4 Prialnik 2 • Hydrostatic equilibrium Pols 2 When not forming or exploding Uniqueness Hydrostatic Equilibrium One of the basic tenets of stellar evolution is the Consider the forces acting upon a spherical mass shell Russell-Vogt Theorem, which states that the mass dm = 4π r 2 dr ρ and chemical composition of a star, and in particular The shell is attracted to the center of the star by a force how the chemical composition varies within the star, per unit area uniquely determine its radius, luminosity, and internal −Gm(r)dm −Gm(r) ρ Fgrav = = dr structure, as well as its subsequent evolution. (4πr 2 )r 2 r 2 where m(r) is the mass interior to the radius r M dm A consequence of the theorem is that it is possible It is supported by the pressure to uniquely describe all of the parameters for a star gradient. The pressure P+dP simply from its location in the Hertzsprung-Russell on its bottom is smaller P Diagram. There is no proof for the theorem, and in fact, than on its top. dP is negative it fails in some instances. For example if the star has rotation or if small changes in initial conditions cause m(r) FP = P(r) i area−P(r + dr) i area large variations in outcome (chaos).