Creating an MA in Songwriting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Fa Ct Or

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price Origin Label Genre Release A40355 A & P Live In Munchen + Cd 2 Dvd € 24 Nld Plabo Pun 2/03/2006 A26833 A Cor Do Som Mudanca De Estacao 1 Dvd € 34 Imp Sony Mpb 13/12/2005 172081 A Perfect Circle Lost In the Bermuda Trian 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Virgi Roc 29/04/2004 204861 Aaliyah So Much More Than a Woman 1 Dvd € 19 Eu Ch.Dr Doc 17/05/2004 A81434 Aaron, Lee Live -13tr- 1 Dvd € 24 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81435 Aaron, Lee Video Collection -10tr- 1 Dvd € 22 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81128 Abba Abba 16 Hits 1 Dvd € 20 Nld Univ Pop 22/06/2006 566802 Abba Abba the Movie 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 29/09/2005 895213 Abba Definitive Collection 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 22/08/2002 824108 Abba Gold 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 21/08/2003 368245 Abba In Concert 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 25/03/2004 086478 Abba Last Video 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Univ Pop 15/07/2004 046821 Abba Movie -Ltd/2dvd- 2 Dvd € 29 Nld Polar Pop 22/09/2005 A64623 Abba Music Box Biographical Co 1 Dvd € 18 Nld Phd Doc 10/07/2006 A67742 Abba Music In Review + Book 2 Dvd € 39 Imp Crl Doc 9/12/2005 617740 Abba Super Troupers 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 14/10/2004 995307 Abbado, Claudio Claudio Abbado, Hearing T 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Tdk Cls 29/03/2005 818024 Abbado, Claudio Dances & Gypsy Tunes 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 12/12/2001 876583 Abbado, Claudio In Rehearsal 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 23/06/2002 903184 Abbado, Claudio Silence That Follows the 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 5/09/2002 A92385 Abbott & Costello Collection 28 Dvd € 163 Eu Univ Com 28/08/2006 470708 Abc 20th Century Masters -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Talking Heads -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Talking Heads / David Byrne / A+ A B+ B C D updated: 09/06/2005 Tom Tom Club / Jerry Harrison / ARTISTS = Artists I´m always looking to trade for new shows not on my list :-) The Heads DVD+R for trade: (I´ll trade 1 DVD+R for 2 CDRs if you haven´t a DVD I´m interested and you still would like to tarde for a DVD+R before contact me here are the simple rules of trading policy: - No trading of official released CD´s, only bootleg recordings, - Please use decent blanks. (TDK, Memorex), - I do not sell any bootleg or copies of them from my list. Do not ask!! - I send CDRs only, no tapes, Trading only !!! ;-), - I don't do blanks & postage or 2 for 1's; fair trading only (CD for a CD or CD for a tape), I trade 1 DVD+R for 2 CDRs if you haven´t a DVD I´m - Pack well, ship airmail interested - CD's should be burned DAO, without 2 seconds gaps between the - Don´t send Jewel Cases, use plastic or paper pockets instead, I´ll do the same tracks, - For set lists or quality please ask, - No writing on the disks please - Please include a set list or any venue info, I´l do the same, - Keep contact open during trade to work out a trade please contact me: [email protected] TERRY ALLEN Stubbs, Austin, TX 1999/03/21 Audience Recording (feat. David Byrne) CD Amarillo Highway / Wilderness Of This World / New Delhi Freight Train / Cortez Sail / Buck Naked (w/ David Byrne) / Bloodlines I / Gimme A Ride To Heaven Boy DAVID BYRNE In The Pink Special --/--/-- TV-broadcast / documentary DVD+R Interviews & music excerpts TV-Show Appearances 1990 - 2004 TV-broadcasts (quality differs on each part) DVD+R I. -

Bigo Worldwide

LISTENING ROOM XPENSIVE DOGS Dog Eat Dog [Rockit Records] Ten years ago, Gary Tanin of Xpensive Dogs was among one of those who relied purely on the internet to create music. Never meeting Japanese musician Toshiyuki Hiraoka , the two traded music files on the net to create the Dogs' debut release. The years have certainly honed Tanin's craft - the production is exquisite and the performance solid. The album opens promisingly. The instrumental title track, with its glimmering guitar, would do any surf movie proud. Hell , with its "this is the place" and "psycho killer" phrasing, and Flowers Grow , with its Latin rhythm, both recall the Talking Heads. However, it is tracks like Sacrifice , Pinochio and The World Has Gone Insane - with their bouncy beat, crafty wordplay and, not to mention, the album's all-star cast - that put the Dogs down the evolutionary path that included bands such as Was (Not Was). Now that Tanin has exorcised some of those ghosts that might have dogged him, perhaps he would like to consider a full-fledged surf album as his next project - after all, the man has a twang that just won't go away. (7) - Stephen Tan Note: Visit www.rockitrecordsusa.com to order the album. BOB FRANK Ride The Restless Wind [Bowstring Records] A much more assured outing than his last album, Pledge of Allegiance (2004), Bob Frank's new Ride The Restless Wind goes down the countrified singer- songwriter road. It features a full band including fiddle player Gabe Witcher (who plays with Merle Haggard), multi-guitarist Jim Monahan and others who bring out the melodies in Frank's love songs. -

Transnational Punk: the Growing Push for Global Change Through a Music-Based Subculture Alexander Lalama Claremont Graduate University, [email protected]

LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 Transnational Punk: The Growing Push for Global Change Through a Music-Based Subculture Alexander Lalama Claremont Graduate University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Lalama, Alexander (2013) "Transnational Punk: The Growing Push for Global Change Through a Music-Based Subculture," LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux/vol3/iss1/9 Lalama: Transnational Punk Lalama 1 Transnational Punk: The Growing Push for Global Change Through a Music-Based Subculture Alexander Lalama, M.A. Claremont Graduate University School of Arts and Humanities Department of English Abstract Little media attention has been devoted to the burgeoning punk scene that has raised alarm abroad in areas such as Banda Aceh, Indonesia and Moscow, Russia. While the punk subculture has been analyzed in-depth by such notable theorists as Dick Hebdige and Stuart Hall, their work has been limited to examining the rise and apparent decline of the subculture in England, rendering any further investigations into punk as looking back at a nostalgic novelty of post- World War II British milieu. Furthermore, the commodification of punk music and style has relegated punk to the realm of an alternative culture in Britain and locally in the U.S. In these current international incarnations, however, a social space for this alternative culture is threatened by severe punishment including what Indonesian police officials have label “moral rehabilitation” and, in the case of Russian punks, imprisonment. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

98 Degrees I Do Adele Rolling in the Deep Allman Brothers Melissa

98 Degrees I Do Adele Rolling In The Deep Allman Brothers Melissa Allman Brothers One Way Out Allman Brothers Midnight Rider American Authors Best Day Of My Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Aretha Franklin Respect Average White Band Pick Up The Pieces Avici Wake Me Up B-52's Love Shack Backstreet Boys I Want It That Way Band, The Cripple Creek Band, The Ophelia Band, The The Weight Band, The Atlantic City Bangles, The Walk Like An Egyptian Beatles, The Come Together Beatles, The Got To Get You Into My Life Beatles, The In My Life Beatles, The Ob La Di Ob La Da Beatles, The Saw Her Standing There Beatles, The Something Beatles, The Twist and Shout Beatles, The Mother Nature's Son Beatles, The Hey Jude Beatles, The Get Back Ben E. King Stand By Me Beyonce Crazy In Love Beyonce Love On Top Bill Haley and The Comets Rock Around The Clock Bill Withers Use Me Billy Joel Movin' Out Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Blind Melon No Rain Blink 182 All The Small Things Bob Carlisle Butterfly Kisses Bob Dylan Forever Young Bob Marley Could You Be Loved Bob Marley I Shot The Sheriff Bob Seger Hollywood Nights Bon Jovi Living On A Prayer Britney Spears Hit Me Baby One More Time Bruce Springsteen Dancing In The Dark Bruce Springsteen Jersey Girl Bruce Springsteen Rosalita Bruce Springsteen Tenth Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruce Springsteen Born To Run Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bryan Adams Summer Of '69 Cake The Distance Cee Lo Green Forget You Chicago 25 or 6 to 4 Cold -

Fictional Worlds and Characters in Art-Making: Fook Island As Exemplar for Art Practice

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). Fictional worlds and characters in art-making: Fook Island as exemplar for art practice by Allen Walter Laing Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Technologiae: Fine Art In the Department of Visual Art Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture University of Johannesburg 8 October 2018 Supervisor: David Paton Co-supervisor: Prof. Brenda Schmahmann The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. Declaration I hereby declare that the dissertation, which I herewith submit for the research qualification Master of Technology: Fine Art to the University of Johannesburg is, apart from recognised assistance, my own work and has not previously been submitted by me to another institution to obtain a research diploma or degree. -

Lester Bangs August 1979

LESTER BANGS AUGUST 1979 One day someone I love said, “You hit me with your eyes.” When I hear David Byrne’s lyrics, I can imagine him feeling the same thing and saying it in language just oblique enough to turn the pain into percussively lapping waters. Are you afraid of air? Well, why not (if not)? David Byrne is. Do you think heaven is nowhere (is vacuum the obverse of oid’svoid)? David Byrne does. How about the animal kingdom: wouldn’t you say they’re a bunch of smug little disease carriers, setting a perfectly rotten example (them being, after all, our elders on that ole evolutionary totem pole) for us so-called human beings who might be a lot more at least interpersonally better off if we wised up and just told all them li’l critters to take a walk? If stuff like that maltomeals round your noggin, you’re in D. Byrne territory for sure, friends. And why not? These are mutant times, and Talking Heads are the most human of mutant groups (hopelessly perfect cross-fertilization); unlike Devo, they actually look good off TV, on a concert stage (in fact, up till now I’d always bemoaned my feeling that their records didn’t come near the excitement of their live sound). I may never forget the first time I saw them at CBGB’s: though they had gotten Jerry Harrison to swat keyboards by then, they were all still a little ragged (if such a word could ever be applied to such rarefied entities) around the edges. -

Ananda Devi's Narrative Strategies and Subversions. Ritu Tyagi Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Ananda Devi's Narrative Strategies and Subversions. Ritu Tyagi Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Tyagi, Ritu, "Ananda Devi's Narrative Strategies and Subversions." (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3561. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3561 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ANANDA DEVI’S NARRATIVE STRATEGIES AND SUBVERSIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Ritu Tyagi B.A., Jawaharlal Nehru University, 1999 M.A., University of California Irvine, 2003 May 2009 ©Copyright 2009 Ritu Tyagi All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation and doctoral degree would not have been possible without the help and support of many individuals. I would like to express my profound gratitude to my dissertation director, Dr. Jack Yeager, for his stimulating suggestions and encouragement. His pleasant smile, optimism, and positivity helped me sail through the most frustrating and depressing moments. My thanks also go to the members of my committee for their support: Dr. -

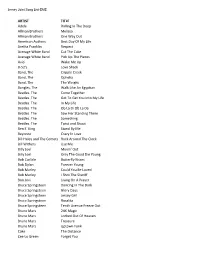

Jersey Joint Song List-EME

Jersey Joint Song List-EME ARTIST TITLE Adele Rolling In The Deep Allman Brothers Melissa Allman Brothers One Way Out American Authors Best Day Of My Life Aretha Franklin Respect Average White Band Cut The Cake Average White Band Pick Up The Pieces Avici Wake Me Up B-52's Love Shack Band, The Cripple Creek Band, The Ophelia Band, The The Weight Bangles, The Walk Like An Egyptian Beatles. The Come Together Beatles. The Got To Get You Into My Life Beatles. The In My Life Beatles. The Ob La Di Ob La Da Beatles. The Saw Her Standing There Beatles. The Something Beatles. The Twist and Shout Ben E. King Stand By Me Beyonce Crazy In Love Bill Haley and The Comets Rock Around The Clock Bill Withers Use Me Billy Joel Movin' Out Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Bob Carlisle Butterfly Kisses Bob Dylan Forever Young Bob Marley Could You Be Loved Bob Marley I Shot The Sheriff Bon Jovi Living On A Prayer Bruce Springsteen Dancing In The Dark Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruce Springsteen Jersey Girl Bruce Springsteen Rosalita Bruce Springsteen Tenth Avenue Freeze Out Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Cake The Distance Cee Lo Green Forget You Jersey Joint Song List-EME Contours, The Do You Love Me Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky Dion Runaround Sue DNCE Cake By The Ocean Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man Eagles, The One of These Nights Earth Wind and Fire September Ed Sheeran Shape of You Elvis Presley A Little Less Conversation Etta James At Last Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The -

Prism Vol 5 No 3.Pdf

PRISM VOL. 5, NO. 3 2015 A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS PRISM About VOL. 5, NO. 3 2015 PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners on complex EDITOR and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; relevant policy Michael Miklaucic and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Connor Christenson Talley Lattimore Jeffrey Listerman Communications Giorgio Rajao Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Hiram Reynolds communications to: COPY EDITORS Editor, PRISM Dale Erickson 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Rebecca Harper Fort Lesley J. McNair Christoff Luehrs Washington, DC 20319 Nathan White Telephone: (202) 685-3442 DESIGN DIRecTOR FAX: Carib Mendez (202) 685-3581 Email: [email protected] ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Gordon Adams Dr. Pauline H. Baker Ambassador Rick Barton Contributions Professor Alain Bauer PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States and Ambassador James F. Dobbins abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to [email protected] Ambassador John E. Herbst (ex officio) with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Dr. David Kilcullen Ambassador Jacques Paul Klein Dr. Roger B. Myerson This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Moisés Naím Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted MG William L.