PPPI Factsheet for MLA Candidates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Action Plan for Multiple Species at Risk in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series Action Plan for Multiple Species at Risk in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide Black-footed Ferret Burrowing Owl Eastern Yellow-bellied Racer Greater Sage-Grouse Prairie Loggerhead Shrike Mormon Metalmark Mountain Plover Sprague’s Pipit Swift Fox 2016 Recommended citation: Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2016. Action Plan for Multiple Species at Risk in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. xi + 127 pp. For copies of the action plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, recovery strategies, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: Landscape photo: South of the Divide, Jones Peak © Native Plant Society, C. Neufeld; Prairie Loggerhead Shrike © G. Romanchuck; Mormon Metalmark © R.L. Emmitt; Swift Fox © Environment and Climate Change Canada, G. Holroyd; Yellow-bellied Racer © Environment and Climate Change Canada, A.Didiuk Également disponible en français sous le titre « Plan d’action pour plusieurs espèces en péril dans le sud-ouest de la Saskatchewan – South of the Divide [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2016. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca Action Plan for Multiple Species in Southwestern Saskatchewan: South of the Divide 2016 Preface The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996)2 agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. -

Govenlock News

Volume 28, Issue 12 January 22, 2015 Next Issue—February 12, 2015 The Reno Reader Informing the residents of reno since 1986 PUBLISHED BY CONSUL MUSEUM INCORPORATED W. G. Jones and A. R. Rowe with a crew Govenlock News of men are putting up ice for the coming (Taken from Maple Creek News season. February 12, 1914) Proud to Sponsor the Consul Museum (online at http://sabnewspapers.usask.ca) B. A. Jahn, our thrifty rancher, is busy The Govenlock Commercial Club gave breaking horses. Mr. Jahn has sold a number of horses to farmers in this area. Consul Grocery one of their popular dancing parties last Store Monday evening. The purpose of these 306-299-2011 parties is to raise money to build a hall. Arthur Sanford has just completed his Raymond Olmsted Among those present were Mr. and Mrs. new house and is getting comfortably Manager settled there. Weekdays: 9-6 W. X. Wright from “The Meadows”, Mr. Consul Farm Supply and Mrs. D. A. Hammond of Stormfield 306-299-2022 Ranch, Mr. and Mrs. Chas. Kennedy, Wm. Govenlock has opened a general Scott Amundson - Manager blacksmith and repair shop. He has se- Weekdays: 8-5:30 Kelvinhurst, D. C. and Gordon McMil- Saturday: 8-12, 1-5 lan, Kelvinhurst, Will McRae and sister, cured the services of Alex Skinner who is MEMBER OWNED Battle Creek, Mr. and Mrs. Ned McKay, one of the best horse shoers in Canada. Six Mile, Mrs. Marshall and family, Bat- Besides the [?] acres sold by W. T. Jones REAMER TRUCKING tle Creek, Paul Hester and sisters of Wil- low Creek and many others. -

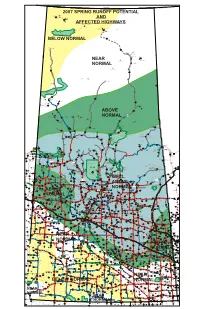

Spring Runoff Highway Map.Pdf

NUNAVUT TERRITORY MANITOBA NORTHWEST TERRITORIES 2007 SPRING RUNOFF POTENTIAL Waterloo Lake (Northernmost Settlement) Camsell Portage .3 999 White Lake Dam AND Uranium City 11 10 962 19 AFFECTEDIR 229 Fond du Lac HIGHWAYS Fond-du-Lac IR 227 Fond du Lac IR 225 IR 228 Fond du Lac Black Lake IR 224 IR 233 Fond du Lac Black Lake Stony Rapids IR 226 Stony Lake Black Lake 905 IR 232 17 IR 231 Fond du Lac Black Lake Fond du Lac ATHABASCA SAND DUNES PROVINCIAL WILDERNESS PARK BELOW NORMAL 905 Cluff Lake Mine 905 Midwest Mine Eagle Point Mine Points North Landing McClean Lake Mine 33 Rabbit Lake Mine IR 220 Hatchet Lake 7 995 3 3 NEAR Wollaston Lake Cigar Lake Mine 52 NORMAL Wollaston Lake Landing 160 McArthur River Mine 955 905 S e m 38 c h u k IR 192G English River Cree Lake Key Lake Mine Descharme Lake 2 Kinoosao T 74 994 r a i l CLEARWATER RIVER PROVINCIAL PARK 85 955 75 IR 222 La Loche 914 La Loche West La Loche Turnor Lake IR 193B 905 10 Birch Narrows 5 Black Point 6 IR 221 33 909 La Loche Southend IR 200 Peter 221 Ballantyne Cree Garson Lake 49 956 4 30 Bear Creek 22 Whitesand Dam IR 193A 102 155 Birch Narrows Brabant Lake IR 223 La Loche ABOVE 60 Landing Michel 20 CANAM IR 192D HIGHWAY Dillon IR 192C IR 194 English River Dipper Lake 110 IR 193 Buffalo English River McLennan Lake 6 Birch Narrows Patuanak NORMAL River Dene Buffalo Narrows Primeau LakeIR 192B St.George's Hill 3 IR 192F English River English River IR 192A English River 11 Elak Dase 102 925 Laonil Lake / Seabee Mine 53 11 33 6 IR 219 Lac la Ronge 92 Missinipe Grandmother’s -

Gazette Part I, March 26, 2021

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART III (REGULATIONS)/CE NUMÉRO NE THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, 26 mars 2021 793 CONTIENT PAS DE PARTIE III (RÈGLEMENTS) The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 117 REGINA, FRIDAY, MARCH 26, 2021/REGINA, vendredi 26 mars 2021 No. 12/nº 12 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I SPECIAL DAYS/JOURS SPÉCIAUX ................................................................................................................................................. 794 PROGRESS OF BILLS/RAPPORT SUR L’ÉTAT DES PROJETS DE LOI (First Session, Twenty-Ninth Legislative Assembly/Première session, 29e Assemblée législative) ................................................ 794 ACTS NOT YET IN FORCE/LOIS NON ENCORE EN VIGUEUR ............................................................................................... 795 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR SUR SANCTION (First Session, Twenty-Ninth Legislative Assembly/Première session, 29e Assemblée législative) ................................................ 799 ACTS IN FORCE BY ORDER OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL/ LOIS EN VIGUEUR PAR DÉCRET DU LIEUTENANT-GOUVERNEUR EN CONSEIL (2020) ........................................ 799 ACTS IN FORCE BY ORDER OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL/ LOIS EN VIGUEUR PAR DÉCRET DU LIEUTENANT-GOUVERNEUR EN CONSEIL (2021) ........................................ 800 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES -

St. Mary and Milk Rivers

Report to THE INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMlllISSION THE DIVISION AND USE MADE OF THE WATERS OF ST. MARY AND MILK RIVERS J. D. McLEOD representing Canada and L. B. LEOPOLD representing United States International Joint Commission, Washington, DOCo ,, and Ottawa, Ontario. Gentlemen: In compliance with the Provisions of Clause VIII (c) of your Order of the 4th October, 1921, directing the division of the waters of St. Mary and Milk Rivers between the United States and Canada, we are transmitting herewith a report on the operations during the irrigation season ended October 31, 1960. ~ccreditedOfficer of Her Majesty. L, B. Leopold Accredited Officer of the United States. Mqrch 17, 9 1961 . (date) Letter of Transmittal to the Commission Introduction ................ 1 Water Supply - St. ~YaryRiver ........... 2 Milk River - and its Eastern Tributaries .......... 3 Division of Water - St. Ivkry River ........ 4 Milk River ............ 7 Eastern Tributaries of Milk River .... 8 ~e'scri~tionof Tables ............. 10 Appendix ................. 12 TABLES Table No. , Natural Flow of St. Mary River at International Boundary and its Division between Canada and the United States ................ 1 Sumnary of Mean Monthly Natural Flow of St. Mary River at International Boundary ............ Summary of ?.lean Monthly United States Share of Natural Flow of St. 1kry River at International Boundary .... Summary of Mean Monthly Canadian Share of Natural Flow of St. Mary River at International Boundary ....... Division of Flow of St. Hary River and its use by Canada Division of .Flows of St. Mary and Milk Rivers and their usebytheunitedstates ............ Determination of Natural Flow of Battle Creek at the International Boundary ............. Determination of Natural Flow of Frenchman River at the International Boundary ......... -

1982 Report to the IJC Appendix B.Pdf

L APPENDIX B TO THE L REPORT TO THE INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION L L ON L THE DIVISION OF THE WATERS OF THE \ ST. MARY AND MILK RIVERS L 1982 L L BY L D. A. DAVIS representing Canada L l L. \ L.. AND L I PHILIP COHEN I ~ representing the United States L L L L I I ii \, CONTENTS Station L Station Name Number Page St. Mary River at International Boundary 05AE027 1-2 L Lake Sherburne at Sherburne, Montana 05AE036 3 L St. Mary Canal at St. Mary Crossing near Babb, Montana 05AE029 4 Milk River at Western Crossing of International Boundary 11AA025 5 L Milk River at Milk River 11AAOOS 6 \ Milk River at Eastern Crossing of International Boundary 11AA031 7 L South Fork Milk River near Babb, Montana 11AA033 8 North Fork Milk River above St. Mary Canal near L Browning, Montana 11AA032 9 North Milk River near International Boundary 11AA001 10 L Lodge Creek below McRae Creek at International Boundary 11AB083 11 L Michele Reservoir near Elkwater 11AB091 12 Greasewood Reservoir near Elkwater 11AB092 13 L Massy Reservoir near Elkwater 11AB104 14 Bare Creek Reservoir near Elkwater 11AB094 15 il Cressday Reservoir near Cressday 11AB097 16 \ L Mitchell Reservoir near Elkwater 11AB099 17 Jaydot Reservoir near Jaydot 11AB098 18 L Middle Creek near Saskatchewan Boundary 11AB009 19 L Middle Creek Reservoir 11AB080 20 Middle Creek Reservoir Main Outlet 11AB113 21 L Middle Creek Reservoir Bedford Outlet 11AB114 22 Middle Creek Reservoir Flood Spillway 11AB115 23 L Middle Creek below Middle Creek Reservoir 11AB001 24 L 1 l- L iii Station L Station Name Number -

Canadian Expeditionary Force

r (ISSUED WITH MILITIA ORDERS, 1915.) Canadian Expeditionary 1 Force 9th Regiment Canadian 1. Mounted Rifles Nominal Roll of Officers, Non -Commissioned Officers and Men. EMBARKATION Port : St. John. 10M-1-16 Ship : S.S. " Califonia." H. Q. 593-2-29 Date: November 23rd, 1915. 9th REGIMENT CANADIAN MOUNTED RIFLES 7 ON STRENGTH. d p Country of TAKEN äzNo. Rank. Name. Former Corps. Name of Next of Kin. Address of Next of Kin. Birth. to Place. Date. Regimental 1 Lieut.-Col Hodson, George Cuthbert S.A Hodson, Mrs. Elsie Douglas Lloydminster, Sask England Lloydminster... Dec. 17, 1914. Major Aikin, James Alexander 29th Horse Aikin, Mrs. Olive M 744 Spadina Crescent, Saskatoon, Sask Canada Saskatoon May 1, 1915. Major Cameron, George Lynch 27th Horse Cameron, Mrs. Rowena c/o W. T. Shaver, Islington, Ont Canada Swift Current... Mar. 22, 1915. Major Cooks, Ernest William 18th Horse Cooks, Mrs. R. W a Mount Forrest, Ont England Moosomin Feb. 1, 1915. Captain Adams, William Alexander 22nd Horse Adams, Thomas 52 University Ave., Belfast, Ire Ireland Lloydminster... Feb. 13, 1915. Captain Buchanan, Gerald Angus B 23rd Rangers Buchanan, Mrs. Helene Marie 1025 Alpine Ave. Rear, Grand Rapids, Mich., U.S.A... Canada Saskatoon Mar. 13, 1915. Captain Gray, Thomas James Can. Mil , Gray, David John Kingston, Ont Canada Lloydminster... Jan. 29, 1915. Captain Moss, Henry Nil Moss, Morris 56 Abington Ave., Northampton, Eng England Winnipeg Feb. 1, 1915. Captain Price, Kenneth Alexander 16th Horse Price, Mrs. Helen Mary Moosomin, Sask England Saskatoon Jan. 1, 1915. Lieutenant Andrews, Geoffrey Stuart 22nd Horse Andrews, W. M. -

February 27, 2014 Next Issue—March 13, 2014

Volume 27, Issue 14 February 27, 2014 Next Issue—March 13, 2014 The Reno Reader Informing the residents of reno since 1986 PUBLISHED BY CONSUL MUSEUM INCORPORATED WE’VE ALWAYS HAD FUN TIMES HERE! Consul’s 100th Anniversary is coming up fast, and we are all look- ing forward to the fun time it will be, the old friends we will enjoy Proud to Sponsor the Consul Museum seeing, and the memories we will share. Consul Grocery Store It seems, not surprisingly, that people from here have always 299-2011 known how to have fun. Here are samples, taken from Our Side Raymond Olmsted Manager of the Hills history books. Weekdays: 9-6 Consul Farm Supply 299-2022 “We were thrilled with the silent home movies that were made by Scott Amundson - Manager Weekdays: 8-5:30 Kurt Browatzke. He showed them at his home, and later at the Saturday: 8-12, 1-5 Merryflat School when everyone gathered there. They were MEMBER OWNED mostly of their cows, building their silo and farm work. He could speed up the machine and the cows would be eating so fast, and REAMER TRUCKING we would all laugh. The age of moving pictures had arrived! What next? That was 1927.” (Bert and Eva Baker story) “Until 1934 the travelling vaudeville tent show came to Vidora every June, called “Chautauqua”, the big top was pitched, pegs Consul, Saskatchewan pounded and for five days (matinees as well as night), various 306-299-4858 entertainers were on stage—musicals, illusionists, comedy, plays and puppets for the kids. -

THE PRAIRIE FARM REHABILITATION ADMINISTRATION and the COMMUNITY PASTURE PROGRAM, 1937-1947 a Thesis Submitted to the College Of

THE PRAIRIE FARM REHABILITATION ADMINISTRATION AND THE COMMUNITY PASTURE PROGRAM, 1937-1947 A Thesis Submitted to the College ofGraduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements For the Degree ofMaster ofArts In the Department ofHistory University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon By Daniel M Balkwill Spring 2002 ©Copyright Daniel M Balkwill, 2002. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries ofthis University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work has been done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use ofthis thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use ofmaterial in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head ofthe Department ofHistory University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 ii Abstract In 1935, following years of drought, economic depression, and massive relief expenditures, the federal government of Canada passed the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act (PFR Act) to arrest soil drifting, improve cultivation techniques, and conserve moisture on the Canadian prairies. -

St Mary Diversion Dam & Canal Headworks Sherburne Dam & Lake

4 St Mary Canal Halls Coulee Siphon 1 Sherburne Dam & Lake Sherburne 2 St Mary Diversion Dam & Canal Headworks 3 St Mary Canal - River Siphon 5 St Mary Canal Drop Structure The St. Mary Supply System and the greater Milk River Project M Cypress Hills ilk Prov. Park Wa Lethbridge Cypress Hills ters Prov. Park . he k r d e C . e B S A S K A T C H E W A N r r e C C t o a s u i ll r nd v e a er e ry St. Mary Canal detail (U.S.) Riv a B w m y D r r a i lo a k t a g e t F n M Kilometers l e o Eastend . e Cypress r C Eastend 4 t Res. 2 A L B E R T A S C 0 10 20 30 Merryfat Lake CANADA F St. Mary Battle Ravenscrag ren Reservoir Magrath 0 10 20 Creek ek ch UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Cre Oxara m 21 a D Milk Wa M n r Miles Robsart e ter M O N T A N A y n s Middle i h e r n l S d 13 r e C Huff Lake i a a e t d v a Creek Res. v e n . na Ri d i M a l A L B E R T A l dian d 18 C a e r M B C y C ilk n L B R anal Wate a o r y rs u d C r 5 h r g . -

Water Quality of Selected Reservoirs in Southwestern Saskatchewan

WATER QUALITY OF SELECTED RESERVOIRS IN SOUTHWESTERN SASKATCHEWAN G.A. Weiterman Irrigation Branch, Saskatchewan Agriculture Outlook, Saskatchewan Water in both surplus and deficiency causes innumerable problems for Saskatchewan. In this paper I wish to discuss the findings of two years of monitoring of a number of surface water bodies used largely for irrigation in southwestern Saskatchewan. Most of us are concerned only with water quantity. Little thought is given to water quality. We simply turn on the tap and take what's there. Having been raised in southern Saskatchewan the purgative effects of local drinking water supplies did not go unnoticed. The same type of digestive upset which occurs to us can occur in our soils if water quality does not meet certain standards (Cameron & Weiterman, 1986). Spring runoff water has always been assumed to be of suitable quality. Due to the Individual Irrigation Assistance program which includes redevelopment of existing irrigation lands, the need for water quality data on a large number of water supplies in southwestern Saskatchewan was identified. Part of the requirement of this program is the issuance of a soil water certificate. Water quality information is required for the completion of this documentation. After realizing the limited amounts of data available through 1984 and the winter of 1985 a scheduled program of collection of 568 RESERVOIRS (CUBIC DECAMETRES) 1 junction Reservoir (10 850) 11 West Val Marie Reservoir (4 190) 17 Cadi I lac Reservoir (2 220) 2 McDougald Reservoir (860) 12 -

MG 259 - Keith Ewart Photograph Collection

MG 259 - Keith Ewart Photograph Collection Dates: 1885-2009 (inclusive), 1977-2009 (predominant). Extent: ~7000 photographs, 125 glass plates, 322 postcards. Biography: Keith Ewart was born on 9 September 1931, and was raised and schooled in Weyburn, Sk. He trained as a psychiatric nurse and spent most of his working career in Moose Jaw. He has lived in Saskatoon since 1989. A photographer by vocation, in 1975 Ewart began taking images of buildings in Saskatchewan. He has published two volumes of his photographic documentation of railway stations and railway buildings. He passed away in 2011. Scope and content: This collection includes images Keith Ewart has taken of structural landmarks, particularly in Saskatchewan, as well as glass plates from a Moose Jaw photographer ca. 1915-1920. The collection also contains some images that were not taken by Ewart, but were collected by him. Arrangement: This fonds was received inn groups of smaller accessions which have been kept in their original groupings. They are organized as such: Pg. 2001-092: Schools/Churches/Railway Buildings/Moose Jaw portraits. 2 2003-128: Court Houses, Town Halls, Banks, Businesses, Houses. / Bridges, Barns 36 2004-118: Canadian National and Pacific Railway Stations 49 2005-119: Rail stations in British Columbia. Manitoba Alberta 55 2006-112: Ontario, Quebec, Maritimes and USA train stations. 62 2007-100: Rail station photos, various 69 2008-096: Railway station postcards and photos (images by others) 80 2009-103: Elevators photos of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. 87 2010-105: Elevators in Saskatchewan and Alberta. 111 Related collections include the Joanne Abrahamson collection (MG 244); the Hans Dommasch fonds (MG 172); the photographic series in the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool fonds (MG 247); and the Community Progress Competitions in the Walter Murray fonds, (MG 1).