972-8886-02-0.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leeds Pottery

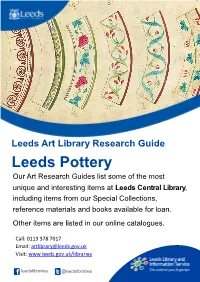

Leeds Art Library Research Guide Leeds Pottery Our Art Research Guides list some of the most unique and interesting items at Leeds Central Library, including items from our Special Collections, reference materials and books available for loan. Other items are listed in our online catalogues. Call: 0113 378 7017 Email: [email protected] Visit: www.leeds.gov.uk/libraries leedslibraries leedslibraries Pottery in Leeds - a brief introduction Leeds has a long association with pottery production. The 18th and 19th centuries are often regarded as the creative zenith of the industry, with potteries producing many superb quality pieces to rival the country’s finest. The foremost manufacturer in this period was the Leeds Pottery Company, established around 1770 in Hunslet. The company are best known for their creamware made from Cornish clay and given a translucent glaze. Although other potteries in the country made creamware, the Leeds product was of such a high quality that all creamware became popularly known as ‘Leedsware’. The company’s other products included blackware and drabware. The Leeds Pottery was perhaps the largest pottery in Yorkshire. In the early 1800s it used over 9000 tonnes of coal a year and exported to places such as Russia and Brazil. Business suffered in the later 1800s due to increased competition and the company closed in 1881. Production was restarted in 1888 by a ‘revivalist’ company which used old Leeds Pottery designs and labelled their products ‘Leeds Pottery’. The revivalist company closed in 1957. Another key manufacturer was Burmantofts Pottery, established around 1845 in the Burmantofts district of Leeds. -

Entre Classicismo E Romantismo. Ensaios De Cultura E Literatura

Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism is an academic series published on- line by the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS) and hosted by the central library of the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Portugal. Studies in Classicism and Romanticism has come into being as a result of the commitment of a group of scholars who are especially interested in English literature and culture from the mid-seventeenth to the mid- nineteenth century. The principal objective of the series is the publication in electronic format of monographs and collections of essays, either in English or in Portuguese, with no pre-established methodological framework, as well as the publication of relevant primary texts from the period c. 1650–c. 1850. Series Editors Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Editorial 2 Sumário Apresentação 4 Maria Luísa Malato Borralho, “Metamorfoses do Soneto: Do «Classicismo» ao «Romantismo»” 5 Adelaide Meira Serras, “Science as the Enlightened Route to Paradise?” 29 Paula Rama-da-Silva, “Hogarth and the Role of Engraving in Eighteenth-Century London” 41 Patrícia Rodrigues, “The Importance of Study for Women and by Women: Hannah More’s Defence of Female Education as the Path to their Patriotic Contribution” 56 Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa, “Sugestões Portuguesas no Romantismo Inglês” 65 Maria Zulmira Castanheira, “O Papel Mediador da Imprensa Periódica na Divulgação da Cultura Britânica em Portugal ao Tempo do Romantismo (1836-1865): Matérias e Imagens” 76 João Paulo Ascenso P. -

Earthenware Pottery Production Techniques and the Bradford Family Pottery of Kingston, MA Martha L

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 6-1-2015 Ubiquitous and Unfamiliar: Earthenware Pottery Production Techniques and the Bradford Family Pottery of Kingston, MA Martha L. Sulya University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sulya, Martha L., "Ubiquitous and Unfamiliar: Earthenware Pottery Production Techniques and the Bradford Family Pottery of Kingston, MA" (2015). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 326. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UBIQUITOUS AND UNFAMILIAR: EARTHENWARE POTTERY PRODUCTION TECHNIQUES AND THE BRADFORD FAMILY POTTERY OF KINGSTON, MA A Thesis Presented by MARTHA L. SULYA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts, Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS June 2015 Historical Archaeology Program © 2015 Martha L. Sulya All rights reserved UBIQUITOUS AND UNFAMILIAR: EARTHENWARE POTTERY PRODUCTION TECHNIQUES AND THE BRADFORD FAMILY POTTERY OF KINGSTON, MA A Thesis Presented by MARTHA L. SULYA Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________________ Christa M. Beranek, Research Scientist, Fiske Center for Archeaological Research Chairperson of Committee _______________________________________________ Stephen A. Mrozowski, Professor ______________________________________________ John M. Steinberg, Senior Scientist, Fiske Center for Archaeological Research ______________________________________ Stephen W. -

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3 http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Lim, Tai Wei “Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the Premodern Global Trading Space” Sino-Japanese Studies 18 (2011), article 3. Abstract: A center-periphery system is one that is not static, but is constantly changing. It changes by virtue of technological developments, design innovations, shifting centers of economics and trade, developmental trajectories, and the historical sensitivities of cultural areas involved. To provide an empirical case study, this paper examines the material culture of Arita/Imari 有田/伊万里 trade ceramics in an effort to understand the dynamics of Japan’s regional and global position in the transition from periphery to the core of a global trading system. Sino-Japanese Studies http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the 1 Premodern Global Trading Space Lim Tai Wei 林大偉 Chinese University of Hong Kong Introduction Premodern global trade was first dominated by overland routes popularly characterized by the Silk Road, and its participants were mainly located in the vast Eurasian space of this global trading area. While there are many definitions of the Eurasian trading space that included the so-called Silk Road, some of the broadest definitions include the furthest ends of the premodern trading world. For example, Konuralp Ercilasun includes Japan in the broadest definition of the silk route at the farthest East Asian end.2 There are also differing interpretations of the term “Silk Road,” but most interpretations include both the overland as well as the maritime silk route. -

64997 Frontier Loriann

[ FRESH TAKE ] Thrown for a Loop factory near his Staffordshire hometown, Stoke-on-Trent. Wedgwood married traditional craftsmanship with A RESILIENT POTTERY COMPANY FACES progressive business practices and contemporary design. TRYING TIMES He employed leading artists, including the sculptor John Flaxman, whose Shield of Achilles is in the Huntington by Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell collection, along with his Wedgwood vase depicting Ulysses at the table of Circe. As sturdy as they were beautiful, Wedgwood products made high-quality earthenware available to the middle classes. his past winter, Waterford Wedgwood found itself teetering on the edge of bankruptcy like a ceramic vase poised to topple from its shelf. As the company struggles A mainstay of bridal registries, the distinctive for survival, visitors to The Tearthenware is equally at home in museums around the world, including The Huntington. Now owned by an Irish firm, the once-venerable pottery manufactory was founded Huntington can appreciate by Englishman Josiah Wedgwood in 1759. As the company struggles for survival, visitors to The Huntington can appre - what a great loss its demise ciate what a great loss its demise would be. A look at the firm’s history reveals that the current crisis is just the most recent would be. of several that Wedgwood has overcome in its 250 years. The story of Wedgwood is one of the great personal and Today, Wedgwood is virtually synonymous with professional triumphs of the 18th century. Born in 1730 into Jasperware, an unglazed vitreous stoneware produced from a family of potters, Josiah Wedgwood started working at the barium sulphate. It is usually pale blue, with separately age of nine as a thrower, a craftsman who shaped pottery on molded white reliefs in the neoclassical style. -

Earthenware Clays

Arbuckle Earthenware Earthenware Clays Earthenware usually means a porous clay body maturing between cone 06 – cone 01 (1873°F ‐ 2152°F). Absorption varies generally between 5% ‐20%. Earthenware clay is usually not fired to vitrification (a hard, dense, glassy, non‐absorbent state ‐ cf. porcelain). This means pieces with crazed glaze may seep liquids. Terra sigillata applied to the foot helps decrease absorption and reduce delayed crazing. Low fire fluxes melt over a shorter range than high fire materials, and firing an earthenware body to near vitrification usually results in a dense, brittle body with poor thermal shock resistance and increased warping and dunting potential. Although it is possible to fire terra cotta in a gas kiln in oxidation, this is often difficult to control. Reduced areas may be less absorbent than the rest of the body and cause problems in glazing. Most lowfire ware is fired in electric kilns. Gail Kendall, Tureen, handbuilt Raku firing and bodies are special cases. A less dense body has better thermal shock resistance and will insulate better. Earthenware generally shrinks less than stoneware and porcelain, and as a result is often used for sculpture. See Etruscan full‐size figure sculpture and sarcophagi in terra cotta. At low temperatures, glaze may look superficial & generally lacks the depth and richness of high fire glazes. The trade‐offs are: • a brighter palette and an extended range of color. Many commercial stains burn out before cone 10 or are fugitive in reduction. • accessible technology. Small electric test kilns may be able to plug into ordinary 115 volt outlets, bigger kilns usually require 208 or 220 volt service (the type required by many air conditioners and electric dryers). -

Thematic Manifestations: an Aesthetic Journey. Jeff Kise East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2004 Thematic Manifestations: an Aesthetic Journey. Jeff Kise East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Kise, Jeff, "Thematic Manifestations: an Aesthetic Journey." (2004). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 877. https://dc.etsu.edu/ etd/877 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thematic Manifestations: an Aesthetic Journey ______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art and Design East Tennessee State University ______________________ In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art ______________________ by Jeff Kise May 2004 _____________________ Don Davis, Chair Anita DeAngelis Catherine Murray Keywords: Ceramics, Simplicity, Aesthetics, Saggar Firing, Flash Firing, Naked Raku ABSTRACT Thematic Manifestations: An Aesthetic Journey by Jeff Kise This thesis, in support of the Master of Fine Arts exhibition entitled Thematic Manifestations at East Tennessee State University, Carroll Reece Museum, Johnson City, Tennessee, March 2-12, 2004, describes in detail three aesthetic themes that are manifested in the work exhibited. The artist discusses his journey in establishing a “criterion of aesthetic values” whereby his work is conceptually developed. The three themes – The Paradox of Simplicity, The Decorative Power of Nature, and The Beauty of the Irregular – are founded on historical and contemporary influences and are further described in practical application of form and process. -

No

I LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED !>t;>rtin>»»ith thr f>rst issue publ>shed >n l947, thc cntin I ii ii) »fili Calindar is now availabl< on mi< ro- film. I'>'rit( I'(>r inl<)rmati<)n <>r scud ord('rs dirc( t t<): I 'nivrrsi< < .'>If< rolilms. Inc., 300:)I /r< h Ro»d, i><nn Arbor, Xfichit,an 4II f06, bhS.A. Leeds Art Collections Fund 'I'h>s >( i>i»tppri>l t(i all 'w'h(l;n'('nt('>'('sll'd it> th< A> ts. 'I'h< I.«ds Art Coll<« >ious Fund is tl>< s<)u>'(( <if''( t uhi> I'undo f()r huff«>» works of'rt Ii)r th< I.r<do (<)ilia ti(in. 0'< >(a>n< ni<ir< subscribing incmbcrs to Siv< / a or upwards ra< h >car. I't'hy not id('n>il'I yours( If with th('>'t (»><if('>') and I cn>f)l(. c'wsan»: '('c('>v('ol«' Ilti Cilli'lliliii''('(', >'<'('<'>>'('nv>tat«)i>s to I'un< Co< er: all ti<ins, privati > i< ws;in<I <irt»;>nis«I visits tu f)lt>('('s of'nt('n Dre)> by f3ill G'ibb, til7B Ilu «ater/i>It deroration im thi s>. In writin>» l<>r an appli( a>i<i>i fi>r»i Io (h(. die» ii hy dli ion Combe, lhe hat by Diane Logan for Bill Hr»n I ii'<i )i(im. l ..II..I inol<l E)»t.. Butt()le)'tii'i't. I i'eili IO 6'i bb, the shoe> by Chelsea Cobbler for Bill Gibb. -

2A Powerpoint Collection Committee March 13, 2021

Collection Committee Saturday, March 13, 2021 III. Old Business c. Collection Inventory VI. Acquisitions a. Gifts Weller Pottery Company (1872-1948) Charles Chilcote (1888–1979) Eocean Floor Vase with Grape Motif Circa 1900 Earthenware and Glaze Gift of Mr. Frank Norman 2020.007.001 VI. Acquisitions b. Purchases Weller Pottery Company (1872-1948) Frederick Hurten Rhead (1880–1942) Hand-Carved Matt Ware Vase Circa 1904 Earthenware and Glaze Purchase, Ayers Collection Fund 2020.009.001 Roseville Pottery Company (1890-1954) Frank Ferrell (1878-1961) Hand-Carved Experimental Vase Circa 1920 Earthenware and Glaze Purchase, Ayers Collection Fund 2020.009.002 VII. Proposed Acquisitions a. Gifts Roseville Pottery Company (1890-1954) Creamware (Floral) Jardiniere Circa 1910 Earthenware, Glaze, and Decals Gift of Dr. Edward A. Council, III IR12/7/2015.008 Owen China Company (1902-1932) Swastika Keramos Three-Handled Vase 1906-1908 Earthenware and Glaze Gift of Dr. Edward A. Council, III IR12/30/2016.001 Weller Pottery Company (1872-1948) Unknown Line, Black and White Vase Dates Unknown Earthenware and Glaze Gift of Dr. Edward A. Council, III IR12/30/2016.002 Clewell Pottery Company (1902–1955) Three-Handled Electroplated Lizard Mug Dates Unknown Porcelain and Copper Gift of Dr. Edward A. Council, III IR12/30/2016.003 J.B. Owens Pottery Company (1885-1907) Art Vellum Mug with Cherry Motif 1905 Earthenware and Glaze Gift of Dr. Edward A. Council, III IR12/30/2016.004 J.B. Owens Pottery Company (1885-1907) Feroza Red Flame Mug 1901 Earthenware and Glaze Gift of Dr. Edward A. Council, III IR12/30/2016.005 Weller Pottery Company (1872-1948) Charles Babcock Upjohn (1866-1951) Experimental Dickensware II Hand-Carved Vase with Image of a Cavalier 1901 Earthenware and Glaze Gift of Dr. -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL Four Literary Protegees of the Lake

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Four Literary Protegees of the Lake Poets: Caroline Bowles, Maria Gowen Brooks, Sara Coleridge and Maria Jane Jewsbury being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Dennis Jun-Yu Low, SA (Oxon) March 2003 Therefore, although it be a history Homely and rude, I will relate the same For the delight of a few natural hearts: And, with yet fonder feeling, for the sake Of youthful Poets, who among these hills Will be my second self when I am gone. Wordsworth Contents Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 2 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... 4 Preface ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: The Lake Poets and 'The Era of Accomplished Women' ............................................ 13 Chapter 2: Caroline Bowles .......................................................................................................... 51 Chapter 3: Maria Gowen Brooks ................................................................................................ 100 Chapter 4: Sara Coleridge ......................................................................................................... -

General Condition Terms for Ceramics the Purpose of This Glossary Is To

General Condition terms for Ceramics The purpose of this glossary is to provide you with a common language for the condition of ceramic items. Hardness the hardness of a ceramic is dependent on the type of clay used, its porosity and firing temperature. The following are simples classifications. Greenware Unfired clay articles. Earthenware- A glazed porous ceramic created by low temperature firing. Majolica or maiolica is tin glazed earthenware and overpainted with oxides developed in Majorca. Similar pottery is known in France as Faience and the UK as Deftware. Porcelain- Kaolin based ceramic body that has been fired between 1200oC- 1400°C vitrifying the composition becoming non porous Bisque-unglazed porcelain Flaws Flaws are defects, visible marks or inclusions made during the manufacturing process that should be included in the description. Damage Damage describes defects made through use, handling, cleaning or storage. Damage includes nicks, cracks, scratches, paint wear and crazing. Abrasion – Scuff marks or areas of concentrated scratches, generally caused by rubbing against another item over time. Accretions-build up or deposit of a foreign materials on a surface Efflorescence-white powdery or hard salt deposits that are located on the surface of the ceramic Spalling- loss from the separation of the ceramic layers due salts migrating through the body and glaze Flaking –lifting and separation of the glazing from the ceramic body without complete loss of the insecure area Light scratches - Scratches which do not score the surface of the item. Can be seen but not felt. Deep scratches - Scratches which score the surface of the item and can be felt with a fingernail. -

Semi-Annual Sale: up to 60% Off

ADVERTISEMENT Semi-Annual Sale: Up to 60% Off ENTERTAINMENT & ARTS Ceramic art, once written off as mere craft, wins a brighter spotlight in the L.A. scene Visitors to the recent Scripps College Ceramic Annual consider “The Guardian,” a 2015 piece of stoneware, underglaze, glaze, resin and milk paint by Kyungmin Park. The longtime event is now joined by two new ceramics biennials, signaling a resurgence for the medium. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) By LEAH OLLMAN APRIL 25, 2018 | 2:44 PM f anything is a sign of the elevated status of ceramics, it's the central place a kiln now occupies on the campus of CalArts. I Once in disrepair because of limited interest, the kiln is in high demand. The studio area for ceramics, once a neglected corner, has become "something of a social hub," reports Thomas Lawson, dean of the School of Art. "Ceramics has flourished at CalArts in sync with its resurgence all over." Painting has been pronounced dead enough times to render the claim meaningless, if not ludicrous. But has clay, that most primordial matter, ever been significant enough as an art medium to merit killing off? In the last decade, however, the spotlight has burned klieg-bright and kiln-hot, to the point where clay's standing in the wider art world has never been higher, the L.A. scene never more alive. Two museums have just launched ceramic biennials, complementing the Scripps College Ceramic Annual, the longest continuously running show of its kind in the country, which recently finished in its 74th iteration.