The Age Order and Children's Right to Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited Richard G. Medlin Stetson University This article reviews recent research on homeschooled children’s socialization. The research indicates that homeschooling parents expect their children to respect and get along with people of diverse backgrounds, provide their children with a variety of social opportunities outside the family, and believe their children’s social skills are at least as good as those of other children. What homeschooled children think about their own social skills is less clear. Compared to children attending conventional schools, however, research suggest that they have higher quality friendships and better relationships with their parents and other adults. They are happy, optimistic, and satisfied with their lives. Their moral reasoning is at least as advanced as that of other children, and they may be more likely to act unselfishly. As adolescents, they have a strong sense of social responsibility and exhibit less emotional turmoil and problem behaviors than their peers. Those who go on to college are socially involved and open to new experiences. Adults who were homeschooled as children are civically engaged and functioning competently in every way measured so far. An alarmist view of homeschooling, therefore, is not supported by empirical research. It is suggested that future studies focus not on outcomes of socialization but on the process itself. Homeschooling, once considered a fringe movement, is now widely seen as “an acceptable alternative to conventional schooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90). This “normalization of homeschooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90) has prompted scholars to announce: “Homeschooling goes mainstream” (Gaither, 2009, p. 11) and “Homeschooling comes of age” (Lines, 2000, p. -

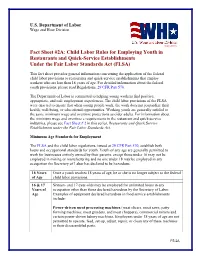

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies FIRST EDITION: March 2017 With support of: European Commission United Nations Development Programme Global Project Joint Task Force on Electoral Assistance for Electoral Cycle Support II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Lead authors Ruth Beeckmans Manuela Matzinger Co-autors/editors Gianpiero Catozzi Blandine Cupidon Dan Malinovich Comments and feedback Mais Al-Atiat Julie Ballington Maurizio Cacucci Hanna Cody Kundan Das Shrestha Andrés Del Castillo Aleida Ferreyra Simon Alexis Finley Beniam Gebrezghi Najia Hashemee Regev Ben Jacob Fernanda Lopes Abreu Niall McCann Rose Lynn Mutayiza Chris Murgatroyd Noëlla Richard Hugo Salamanca Kacic Jana Schuhmann Dieudonne Tshiyoyo Rana Taher Njoya Tikum Sébastien Vauzelle Mohammed Yahya Lea ZoriĆ Copyeditor Jeff Hoover Graphic desiger Adelaida Contreras Solis Disclaimer This publication is made possible thanks to the support of the UNDP Nepal Electoral Support Project (ESP), generously funded by the European Union, Norway, the United Kingdom and Denmark. The information and views set out in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UN or any of the donors. The recommendations expressed do not necessarily represent an official UN policy on electoral or other matters as outlined in the UN Policy Directives or any other documents. Decision to adopt any recommendations and/or suggestions presented in this publication are a sovereign matter for individual states. Youth -

Youth Voter Participation

Youth Voter Participation Youth Voter Participation Involving Today’s Young in Tomorrow’s Democracy Copyright © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) 1999 All rights reserved. Applications for permission to reproduce all or any part of this publication should be made to: Publications Officer, International IDEA, S-103 34 Stockholm, Sweden. International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will respond promptly to requests for permission for reproduction or translation. This is an International IDEA publication. International IDEA’s publications are not a reflection of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA’s Board or Council members. Art Direction and Design: Eduard âehovin, Slovenia Illustration: Ana Ko‰ir Pre-press: Studio Signum, Slovenia Printed and bound by: Bröderna Carlssons Boktryckeri AB, Varberg ISBN: 91-89098-31-5 Table of Contents FOREWORD 7 OVERVIEW 9 Structure of the Report 9 Definition of “Youth” 9 Acknowledgements 10 Part I WHY YOUNG PEOPLE SHOULD VOTE 11 A. Electoral Abstention as a Problem of Democracy 13 B. Why Participation of Young People is Important 13 Part II ASSESSING AND ANALYSING YOUTH TURNOUT 15 A. Measuring Turnout 17 1. Official Registers 17 2. Surveys 18 B. Youth Turnout in National Parliamentary Elections 21 1. Data Sources 21 2. The Relationship Between Age and Turnout 24 3. Cross-National Differences in Youth Turnout 27 4. Comparing First-Time and More Experienced Young Voters 28 5. Factors that May Increase Turnout 30 C. Reasons for Low Turnout and Non-Voting 31 1. Macro-Level Factors 31 2. -

Reconsidering the Minimum Voting Age in the United States

Reconsidering the Minimum Voting Age in the United States Benjamin Oosterhoff1, Laura Wray-Lake2, & Daneil Hart3 1 Montana State University 2 University of California, Los Angeles 3 Rutgers University Several US states have proposed bills to lower the minimum local and national voting age to 16 years. Legislators and the public often reference political philosophy, attitudes about the capabilities of teenagers, or past precedent as evidence to support or oppose changing the voting age. Dissenters to changing the voting age are primarily concerned with whether 16 and 17-year-olds have sufficient political maturity to vote, including adequate political knowledge, cognitive capacity, independence, interest, and life experience. We review past research that suggests 16 and 17-year-olds possess the political maturity to vote. Concerns about youths’ ability to vote are generally not supported by developmental science, suggesting that negative stereotypes about teenagers may be a large barrier to changing the voting age. Keywords: voting, adolescence, rights and responsibility, politics Voting represents both a right and responsibility within tory and rooted in prejudiced views of particular groups’ ca- democratic political systems. At its simplest level, voting is pabilities. Non-white citizens were not granted the right to an expression of a preference (Achen & Bartels, 2017) in- vote until the 1870s, and after being legally enfranchised, tended to advance the interests of oneself or others. Voting literacy tests were designed to prevent people of color from is also a way that one of the core qualities of citizenship— voting (Anderson, 2018). The year 2020 marks the 100th participation in the rule-making of a society—is exercised. -

Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability Within the Criminal

Duquesne Law Review Volume 55 Number 1 Drafting Statutes and Rules: Article 8 Pedagogy, Practice, and Politics 2017 Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability within the Criminal Justice System: Raising the Age of Majority to Age 21 Based on the Conclusions of Scientific Studies egarr ding Neurological Development and Culpability of Young-Adult Offenders Carly Loomis-Gustafson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Juvenile Law Commons Recommended Citation Carly Loomis-Gustafson, Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability within the Criminal Justice System: Raising the Age of Majority to Age 21 Based on the Conclusions of Scientific Studies egarr ding Neurological Development and Culpability of Young-Adult Offenders, 55 Duq. L. Rev. 221 (2017). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol55/iss1/8 This Student Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability within the Criminal Justice System: Raising the Age of Majority to Age 21 based on the Conclusions of Scientific Studies Regarding Neurological Development and Culpability of Young-Adult Offenders Carly Loom is-Gustafson* ABSTRACT The criminaljustice system determines a criminalactor's liability based primarily on the age of the actor at the time of the offense, adhering to a rule instituted by arbitrary designationof adulthood at the age of eighteen. Solely, this line determines the degree of treat- ment a criminal defendant will receive within the system, with more punitive measures being reserved for adult offenders and greater re- habilitative efforts made for juvenile offenders. -

Child Marriage and POVERTY

Child Marriage and POVERTY Child marriage is most common in the world’s poorest countries and is often concentrated among the poorest households within those countries. It is closely linked with poverty and low levels of economic development. In families with limited resources, child marriage is often seen as a way to provide for their daughter’s future. But girls who marry young are IFAD / Anwar Hossein more likely to be poor and remain poor. CHILD MARRIAGE Is INTIMATELY shows that household economic status is a key factor in CONNEctED to PovERTY determining the timing of marriage for girls (along with edu- cation and urban-rural residence, with rural girls more likely Child marriage is highly prevalent in sub- to marry young). In fact, girls living in poor households are Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, the approximately twice as likely to marry before 18 than girls two most impoverished regions of the world.1 living in better-off households.4 • More than half of the girls in Bangladesh, Mali, Mozam- In Côte d’Ivoire, a target country for the President’s Emer- bique and Niger are married before age 18. In these same gency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), girls in the poorest countries, more than 75 percent of people live on less than $2 a day. In Child Marriage in the Poorest and Richest Households Mali, 91 percent of the in Select Countries population lives on less 80 than $2 a day. 2 70 • Countries with low GDPs tend to have a higher 60 prevalence of child mar- riage. -

Gendered Ageism in the Canadian Workforce the Economic, Social and Emotional Effects of Isolating Older Women from the Workplace

Gendered Ageism in the Canadian Workforce The economic, social and emotional effects of isolating older women from the workplace By Sophie Beaton Social Connectedness Fellow 2018 Samuel Centre for Social Connectedness www.socialconnectedness.org August 2018 Table of contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Gendered Ageism 5 Gendered Ageism in the Workforce 7 Methodology 9 Findings from Interviews 12 Discussion 21 Bibliography 26 1 Abstract This research was conducted to examine the impacts of gendered ageism in the workplace for women over 50. The aim of this research was to determine how older women are impacted on an economic, social and emotional level when they experience this type of discrimination at work. The findings show that women over 50 are both unfairly forced out of their positions and have unjustified difficulty reentering the workforce, which then negatively impacts components of their lives such as economic stability, self-esteem, social connectedness and emotional well- being. To alleviate these impacts, it is recommended that programs and policies are put in place that make it easier for women to pursue legal action against their employer, and that social groups are created that provide networking opportunities and emotional support for older women. Key Words: gender, age, discrimination, workforce, women, employment, isolation, stereotype 2 Introduction Across North America, the workforce is aging. As demographics shift, so will the working age population making it essential that older individuals continue to remain active -

AMA Journal of Ethics® January 2021, Volume 23, Number 1: E64-69

AMA Journal of Ethics® January 2021, Volume 23, Number 1: E64-69 MEDICINE AND SOCIETY: PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLE Cautions About Medicalized Dehumanization Alexandra Minna Stern, PhD Abstract Critical lessons can be gleaned by examining 2 of the most salient relationships between racism and medicine during the Holocaust: (1) connections between racism and dehumanization that have immediate, lethal, deleterious, longer-term consequences and (2) intersections of racism and other forms of hatred and bigotry, including discrimination against people with disabilities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people; and social and religious minorities. When considered in the US context, these lessons amplify need for reflection about the history of eugenics and human experimentation and about the persistence of racism and ableism in health care. To claim one AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM for the CME activity associated with this article, you must do the following: (1) read this article in its entirety, (2) answer at least 80 percent of the quiz questions correctly, and (3) complete an evaluation. The quiz, evaluation, and form for claiming AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM are available through the AMA Ed HubTM. Racism, Medicine, and Dehumanization During the Third Reich The murder of 6 million Jews and millions of other people in Nazi Germany was made possible by dehumanization on a pervasive and catastrophic scale. In her classic book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt analyzes historical conditions that gave rise to Nazism, arguing that an overriding impulse of Nazi ideology was to deprive its victims initially of their juridical and civil rights and next of their existential rights, ultimately denying perceived enemies of “the right to have rights.”1 This process turned social and human beings into “bare life,” naked and exposed to the regime’s brutalities.2,3 Nazi Germany, of course, was not the first dehumanizing regime. -

Why Is Ageism Unacceptable?

What is ageism? Ageism, discrimination based on a person’s age, has a dramatic detrimental effect on older people but this is often not acknowledged. We want to highlight age discrimination as a major issue that needs to be addressed in order to ensure the fair treatment of older people. Some of these situations may be familiar to you: Losing your job because of your age Being refused interest-free credit a new credit card or car insurance because of your age Finding that an organisations attitude to older people results in you receiving a lower quality of service Age limits on benefits such as Disability Living Allowance A doctor deciding not to refer you to a consultant because you are ‘too old Ageism is illegal in employment, training and education. Why is Ageism unacceptable? Ageism is not obvious. You may not be aware it's happening but it may result in you receiving different treatment. Until the Equality Bill comes into force in 2012, making ageism unlawful in the provision of products and services where it has negative or harmful consequences, there is no legal remedy to stop it. But we’re determined to highlight its effects and campaign against it. Ageism - often referred to as age discrimination - exists in many areas of life and not only causes personal hardship and injustice but also harms the economy. We are campaigning to end ageism in all walks of life. We believe older people should have equal rights to participate and enjoy all the benefits of a modern society. Am I being discriminated against? It’s not always easy to spot age discrimination as there are several kinds some of which are subtle and unintentional: Direct discrimination This means treating someone less favourably because of their age or because of the age they appear to be. -

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion – Glossary of Terms Ableism

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion – Glossary of Terms Ableism- discrimination against persons with mental and/or physical disabilities; social structures that favor able-bodied individuals. (The National Multicultural Institute) Acculturation- the process of learning and incorporating the language, values, beliefs, and behaviors that makes up a distinct culture. This concept is not to be confused with assimilation, where an individual or group may give up certain aspects of its culture in order to adapt to that of the prevailing culture. (The National Multicultural Institute) Affirmative Action- proactive policies and procedures for remedying the effect of past discrimination and ensuring the implementation of equal employment and educational opportunities, for recruiting, hiring, training and promoting women, minorities, people with disabilities and veterans in compliance with the federal requirements enforced by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP). (Society for Human Resources Management) Ageism- discrimination against individuals because of their age, often based on stereotypes. (The National Multicultural Institute) Ally- a person who takes action against oppression out of a belief that eliminating oppression will benefit members of targeted groups and advantage groups. Allies acknowledge disadvantage and oppression of other groups than their own, take supportive action on their behalf, commit to reducing their own complicity or collusion in oppression of these groups, and invest in strengthening their own knowledge and awareness of oppression. (Center for Assessment and Policy Development) Anti-Oppression - Recognizing and deconstructing the systemic, institutional and personal forms of disempowerment used by certain groups over others; actively challenging the different forms of oppression. (Center for Anti-Oppressive Education) Bias - a positive or negative inclination towards a person, group, or community; can lead to stereotyping. -

What Does a Job Candidate's Age Signal to Employers?

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12849 What Does a Job Candidate’s Age Signal to Employers? Hannah Van Borm Ian Burn Stijn Baert DECEMBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12849 What Does a Job Candidate’s Age Signal to Employers? Hannah Van Borm Ghent University Ian Burn University of Liverpool and SOFI Stijn Baert Ghent University, University of Antwerp, Université catholique de Louvain, IZA and IMISCOE DECEMBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12849 DECEMBER 2019 ABSTRACT What Does a Job Candidate’s Age Signal to Employers?* Research has shown that hiring discrimination is a barrier for older job candidates in many OECD countries.